I saw the sergeant deliberately aim at and hit two Indians who had run into the ravine.

–Captain Winfield S. Edgerly

The first sergeant of G Troop at Wounded Knee was twenty-five-year-old Frederick E. Toy, a native of Buffalo, New York. He was two years into his second enlistment, and according to army records, was almost twenty-nine. As with many troopers, Toy claimed he was twenty-one when he enlisted at the age of 18, so as to avoid the requirement for parental permission to serve. This made him one of the two youngest first sergeants at Wounded Knee (John B. Turney was twenty-three). In addition to being Captain Edgerly’s most trusted enlisted soldier, he was also one of the best sharpshooters in the regiment, a skill he used to deadly effect on December 29, 1890.[1]

(Click to enlarge) Inset of the map that Major General N. A. Miles included with this 1891 annual report.[2]

(Click to enlarge) Captain W. S. Edgerly’s original letter recommending Sergeant F. E. Toy for the Medal of Honor.[4]

Captain Edgerly took up his pen on April 18, exactly a month after making the original recommendation, and provided the following details:

The words “while shooting hostile Indians” in this communication were used by me advisedly and constitute the specific acts for which I recommended 1st Sergeant Toy. The fight was unexpected and I saw the sergeant deliberately aim at and hit two Indians who had run into the ravine; his coolness and bravery exciting my admiration at the time. I don’t believe in conferring medals indiscriminately, and for ordinary bravery; if I did, I would recommend about forty men of my troop for their splendid conduct on 29th & 30th of December, 1890, but I believe that 1st Sergeant Toy deserves the honor for which I recommended him.[5]

(Click to enlarge) Endorsements on the recommendation of First Sergeant F. E. Toy for the Medal of Honor.[6]

The Congress to

1st Sergt. Frederick E. Toy,

Troop G, 7th Cavalry,

for bravery at Wounded Knee Creek, S.D.

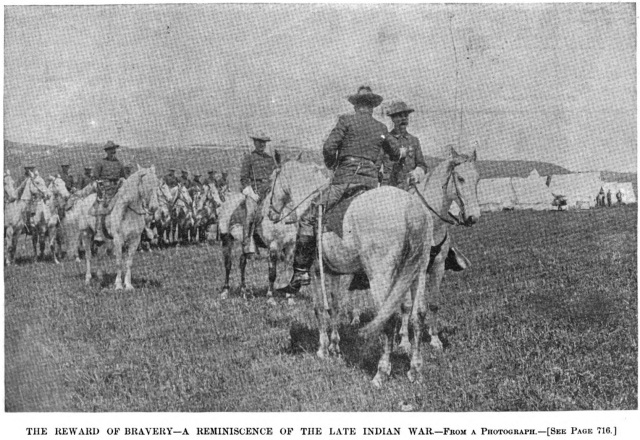

The Assistant Adjutant General mailed the medal on May 26, and Trumpeter Walter O. Cook, Troop D, 7th Cavalry, signed for it at Fort Riley on behalf of “Gen’l Forsyth” on June 1st. Two days earlier G Troop had marched in the Junction City Memorial Day parade as part of the 7th Cavalry Regiment’s second “Nickle Plate” battalion. However, earlier that day, the Second Battalion left Fort Riley and went into camp to conduct target range and drills until July 15th. This provided a rare opportunity for the 7th Cavalry and First Sergeant Toy. Just outside of camp, Captain Edgerly formed up his troop, mounted on their white cavalry horses under the command of Lieutenant E. P. Brewer. Toy reported to Edgerly in front of the troop, and the captain pinned the Medal of Honor on his first sergeant. A photographer was on hand to record the moment, and an article with accompanying picture appeared in the September 19 edition of Harper’s Weekly.[7]

Captain W. S. Edgerly presents the Medal of Honor to First Sergeant F. E. Toy in front of Troop G, 7th Cavalry Regiment.[8]

Fred E. Toy had left home by the time he was eighteen and made his way to Chicago where he was recruited to enlist in G Troop, 7th Cavalry, on October 16, 1883, by Captain S. M. Whitside of the 6th Cavalry. Toy listed his occupation as a butcher, no doubt having apprenticed under his father. He stood five feet, seven and a half inches tall, had black hair, hazel eyes, and a fair complexion. Serving with G Troop in the Dakota Territory at Forts Yates and Keogh, Toy completed his five-year enlistment at Fort Riley, Kansas, as a sergeant with an excellent service characterization. He was one of the finest marksmen in the Army. In August 1891, First Sergeant Toy finished first for cavalrymen in the Department of Missouri shooting contest held at Fort Leavenworth. The following year he was awarded the distinguished marksman badge at the Army competition at Fort Sheridan; the members of his troop presented him with a gold watch and chain to commemorate his achievement. Toy reenlisted six more times, serving twenty seven years, including service as a First Sergeant, Quartermaster Sergeant, and completing his service as an Ordnance Sergeant on the Post Noncommissioned Staff (P.N.C.S.) at Fort Niagara, New York. According to a New York Times article, Toy had also served as an orderly to President Theodore Roosevelt.[10]

Fred E. Toy had left home by the time he was eighteen and made his way to Chicago where he was recruited to enlist in G Troop, 7th Cavalry, on October 16, 1883, by Captain S. M. Whitside of the 6th Cavalry. Toy listed his occupation as a butcher, no doubt having apprenticed under his father. He stood five feet, seven and a half inches tall, had black hair, hazel eyes, and a fair complexion. Serving with G Troop in the Dakota Territory at Forts Yates and Keogh, Toy completed his five-year enlistment at Fort Riley, Kansas, as a sergeant with an excellent service characterization. He was one of the finest marksmen in the Army. In August 1891, First Sergeant Toy finished first for cavalrymen in the Department of Missouri shooting contest held at Fort Leavenworth. The following year he was awarded the distinguished marksman badge at the Army competition at Fort Sheridan; the members of his troop presented him with a gold watch and chain to commemorate his achievement. Toy reenlisted six more times, serving twenty seven years, including service as a First Sergeant, Quartermaster Sergeant, and completing his service as an Ordnance Sergeant on the Post Noncommissioned Staff (P.N.C.S.) at Fort Niagara, New York. According to a New York Times article, Toy had also served as an orderly to President Theodore Roosevelt.[10]

On November 8, 1893, while stationed with the 7th Cavalry at Fort Riley, Toy married Alice Mary Morrow in Junction City, Kansas. She was a 24-year-old Irish immigrant born in County Tyrone. Together they had four children: Winifred Catherine, the future Mrs. Frederick William Feigenbaum, born in 1895 at Fort Clark, Texas; Edward Frederick, born in 1896 at Fort Apache, Arizona Territory; Marie A., born in 1898 also at Fort Apache; and Mercedes, born in 1905 at Fort Sheridan, Illinois.[11]

This 1914 photograph of Fred E. Toy as Commander of Camp No. 7, United Spanish War Veterans, appeared in the May 31, 1914, edition of the Buffalo Courier. Toy is wearing his Indian Wars Campaign Medal (no. 617), Distinguished Marksman Badge, Medal of Honor, U.S.W.V. Post Commander Medal, Society of the Army and Navy Union of the United States Medal, the U.S.W.V. Medal, and other society medals.[13]

Tragedy struck the family in 1916 when the Toy’s 18-year-old daughter, Marie, died at home after a long and tedious illness with pulmonary complications. Alice Toy was devastated, but the retired cavalryman had little time to mourn as the Nation once again moved to a war footing. On July 25, 1917, Toy was recalled to active duty, and reported to Fort Niagara to serve in the Army Quartermaster Corps. He was trained in stevedore operations at Newport News, Virginia, and later at Hoboken, New Jersey, where he was commissioned a Quartermaster captain and assigned to the 302nd Stevedore Regiment. He was shipped overseas as part of the AEF in December 1917. Interestingly, Toy later served in France in the 303rd Stevedore Regiment, which was commanded by Colonel William G. Austin, a fellow former 7th Cavalry trooper who also was awarded the Medal of Honor for actions at Wounded Knee. After eighteen months in Europe, Captain Toy, now in command of the 852nd Transportation Company, returned to Camp Mills, New York, in July 1919 and was demobilized at the end of the month at Camp Dix, New Jersey, when he reverted to his retired rank of Ordnance Sergeant.[14]

Circa 1930, Fred E. Toy pictured with his second wife, the former Mrs. Margaret Hood Crawford.[16]

The United States was not finished with expressing its appreciation and recognition of Toy’s service to the nation. By a special act of Congress in 1932, Toy was promoted on the retired list from Master Sergeant to Captain, the highest rank in which he had served. The announcement of his promotion ran in the Niagara Falls Gazette on July 10, 1933. Three weeks later the veteran of the Indian Wars, Spanish-American War, and World War I passed away on August 5 at the age of sixty-eight. He was laid to rest in the Riverdale Cemetery in Lewiston, Niagara County, New York, alongside his first wife and two daughters. His second wife, Margaret died in 1945 and was also buried in the same section. Toy’s original grave marker was granite and said simply “Capt. Frederick E. Toy, 1866-1933, U.S. Army Retired.” Later, a marker from the Congressional Medal of Honor Society was placed on his grave.[17]

Congressional Medal of Honor Society marker at the grave of Captain Frederick Ernest Toy at the Riverdale Cemetery, Lewiston, New York.[18]

Following is the full photograph and article that appeared in Harper’s Weekly in 1891 detailing Captain Winfield S. Edgerly presenting Frederick E. Toy with the Medal of Honor. Note that the writer of the article, which is really more an opinion piece, misspelled the Soldier’s name.

Decoration of an American Soldier.

These times of ours are devoid of sentiment, and modern republics are so decidedly matter-of-fact that their ingratitude is proverbial. The United States is no exception; even the enormous pension roll is the outcome of political jugglery, and not sentiment, as some dyed-in-the-wool people would have us to believe. Once in a while, however, Congress is attacked with a fit of generosity, and votes a medal to some man for some act of daring and bravery, but ere long grows ashamed of its outburst, and when the medal is ready to be delivered, it is sent in a sealed envelope to the man whom it is desired to honor. There is no outburst of enthusiasm over the presentation, no public honor beyond a newspaper report of the proceedings of Congress. The attitude of the men who passed the bill appropriating the few dollars seems to be, “Well, we spent the money, you know, but publicity is a thing to be shunned; perhaps the people might object if it were generally known that their surplus was squandered in this way”; and then the honorable gentlemen go back and try to beat the record in passing pension bills. And the recipient of the honor, when he opens the sealed envelope and finds the medal, is, of course, highly pleased, and then, with the modesty of bravery, goes forthwith and hides the decoration and says nothing about it, lest he be accused of bragging. They know how to do these things differently on the other side—even in republican France.

It is pleasant, therefore, to note an exception to the rule. We are glad to be able to enthuse over the recognition of bravery in public, and to honor the brave man. Out in Kansas recently an interesting ceremony took place, which was the first of its kind, as far as known of, in this country. First Sergeant F. E. Foy [sic: Toy] distinguished himself for bravery at the battle of Wounded Knee. A Medal of Honor was therefore voted to him. When the medal was ready, the sergeant was at Fort Riley, Kansas, with his troop, and the good sense of somebody omitted the sealed envelope presentation, and substituted a formal ceremony. “G” Troop drew up in line, mounted, with Lieutenant Brewer in command. Sergeant Foy was called to the front by Captain Edgerly, who, after a brief complimentary speech, pinned the medal on the sergeant’s breast. The captain retired. Sergeant Foy wheeled about, and Lieutenant Brewer presented arms to him and saluted him before his troop, thus honoring the award of merit. It is pleasant to chronicle such a ceremony, and everybody with a spark of loyalty delights in the public recognition. Perhaps the republic as a whole will realize the extent of individual sentiment, and consign the envelope, unused, to oblivion, where it belongs.[18]

Endnotes:

[1] Ancestry.com, U.S. Army, Register of Enlistments, 1798-1914 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007), Years: 1878-1884; Last Name: P-Z, Image: 329, Line: 259.

[2] Inset to “Map No. 3 Scene of the Fight with Big Foot’s Band December 29, 1890, Showing position of troops when first shot was fired, From sketches made by Lt. S. A. Cloman, Acting Engineer Officer Division of the Missouri,” Nelson A. Miles Papers, Sioux War, 1890-1891, Wounded Knee, Pullman Strike, Commanding General, box 4 of 10, repository at the U.S. Army Military History Institute, Carlisle, PA. Photograph of map taken by Samuel L. Russell, copyright Russell Martial Research, 2017.

[3] Adjutant General’s Office, Medal of Honor file for Matthew H. Hamilton, Principal Record Division, file 3466, Record Group: 94, Stack area: 8W3, Row: 7, Compartment 30, Shelf: 2. Research conducted by Vonnie S. Zullo of The Horse Soldier Research Service.

[4] Adjutant General’s Office, Medal of Honor file for Frederick E. Toy, Adjutant General’s Office Document File 943698, Box: 3854, Record Group: 94, Stack area: 8W3, Row: 7, Compartment 30, Shelf: 2. Research conducted Mar. 6, 2017, by Vonnie S. Zullo of The Horse Soldier Research Service.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.; “Memorial Day,” The Junction City Tribune (Junction City, KS: 4 Jun 1891), 7; “On the Target Range,” The Junction City Tribune (Junction City, KS: 11 Jun 1891), 3; photograph cropped from “The Reward of Bravery,” Harper’s Weekly vol. 35, no. 1813 (New York: 19 Sep 1891), 713.

[8] “The Reward of Bravery,” Harper’s Weekly vol. 35, no. 1813 (New York: 19 Sep 1891), 716.

[9] New York State Abstracts of World War I Military Service, 1917–1919, Adjutant General’s Office. Series B0808, New York State Archives, Albany, New York; Ancestry.com, United States Federal Census (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009), Images reproduced by FamilySearch, Year: 1850, Census Place: Buffalo Ward 4, Erie, New York, Roll: M432_502, Page: 363B, Image: 230; Year: 1860, Census Place: Buffalo Ward 5, Erie, New York, Roll: M653_746, Page: 812, Family History Library Film: 803746; Year: 1870, Census Place: Buffalo Ward 5, Erie, New York, Roll: M593_933, Page: 614A, Family History Library Film: 552432; Year: 1880, Census Place: Buffalo, Erie, New York, Roll: 829, Page: 386B, Enumeration District: 134; Year: 1900, Census Place: Buffalo Ward 18, Erie, New York, Page: 26, Enumeration District: 0145; Year: 1910, Census Place: Buffalo Ward 7, Erie, New York, Roll: T624_942, Page: 7B, Enumeration District: 0064, FHL microfilm: 1374955; Buffalo Morning Express and Illustrated Buffalo Express (Buffalo, NY: 10 Dec 1870), 4; Buffalo Evening News (Buffalo, NY: 07 Oct 1913), 1.

[10] Adjutant General’s Office, Medal of Honor file for Frederick E. Toy, Adjutant General’s Office Document File 943698, Box: 3854, Record Group: 94, Stack area: 8W3, Row: 7, Compartment 30, Shelf: 2, “Descriptive List, Military Record, and Statement of Accounts,” 14 Nov 1904; Chicago Tribune (Chicago: 21 Aug 1891), 6; Detroit Free Press (Detroit: 13 Nov 1892), 10; U.S. Army, Register of Enlistments, 1798-1914, year: 1878-1884, Name: P-Z, image: 329, line: 259; year: 1885-1890, Name: L-Z, image: 488, line: 203; year: 1893-1897, Name: L-Z, image: 420, line: 246; year: 1898, Name: L-Z, image: 588, line: 1399; year: 1901 May – 1902, Name: L-Z, image: 523, line: 957; year: 1904 Jul – 1905 Dec, Name: L-Z, image: 497, line: 935; year: 1906-1907, Name: L-Z, image: 516, line: 804; “Sergt. Toy, Medal of Honor Man, Placed on Retired List,” New York Times (New York: 15 Jan 1911), 17.

[11] Marriage Records. Kansas Marriages (Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2016), Various Kansas County District Courts and Kansas State Historical Society, Topeka, Kansas, Film Number: 001685972; USFC, Year: 1910, Census Place: Porter, Niagara, New York, Roll: T624_1049, Page: 8B, Enumeration District: 0130, FHL microfilm: 1375062; Year: 1920, Census Place: Niagara Falls Ward 10, Niagara, New York, Roll: T625_1242, Page: 34B, Enumeration District: 124;

[12] “Captain F. E. Toy, Railroad Police Official, Passes,” Niagara Falls Gazette (Niagara Falls, NY: 7 Aug 1933), 1; Buffalo Courier (Buffalo, NY: 24 May 1914), 77.

[13] Mary Ellen Barnes, contributor, “Fred E. Toy in Uniform,” Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/tree/114019178/photo/65092408-8ca9-4ba6-866b-cea50aebda15), accessed 10 Apr 2018; “Captain Fred E. Toy,” Niagara Falls Gazette, (Niagara Falls, NY: 8 Aug 1933), 6; Jerome A. Greene, email to Samuel L. Russell dated 14 Mar 2018, Subject: Frederick Ernest Toy.

[14] Buffalo Morning Express and Illustrated Buffalo Express (Buffalo, NY: 5 Dec 1916), 10; Buffalo Evening News (Buffalo, NY: 5 Dec 1916), 2; Ancestry.com, New York, Abstracts of World War I Military Service, 1917-1919 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2013), Adjutant General’s Office, Series B0808, New York State Archives, Albany, New York, Name Range: Tirrell, A – Valentine, I (Box 722).

[15] “Captain F. E. Toy, Railroad Police Official, Passes,” Niagara Falls Gazette (Niagara Falls, NY: 7 Aug 1933), 1; “Miss M. Toy Died Suddenly,” Niagara Falls Gazette (Niagara Falls, NY: 16 Jul 1923), 4; “Mrs. Alice Toy Taken by Death,” The Niagara Falls Gazette (Niagara Falls: NY: 2 Dec 1927), 34; “Deaths,” Niagara Falls Gazette (Niagara Falls, NY: 5 Nov 1945), 20.

[16] Mary Ellen Barnes, contributor,”Fred E Toy with Margaret Crawford, sec wife and others,” Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/tree/114019178/photo/9f9f1357-d2f5-4629-b637-79fdfd8635cd), accessed 10 Apr 2018.

[17] “Retired as Captain,” Niagara Falls Gazette (Niagara Falls, NY: 10 Jul 1933), 18; “Deaths,” Niagara Falls Gazette (Niagara Falls, NY: 5 Nov 1945), 20; Don Morfe, “Frederick Ernest Toy,” FindAGrave (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/8242471/frederick-ernest-toy), accessed 10 Apr 2018 .

[18] Decoration of an American Soldier,” Harper’s Weekly vol. 35, no. 1813 (New York: 19 Sep 1891), 716. Some historians (e.g., David W. Grua in Surviving Wounded Knee) have taken this article as historical fact that Toy’s presentation of the Medal of Honor was the first time that the medal was ceremoniously bestowed. The article is an opinion piece in which the author merely presents his misinformed belief that the ceremony was the first of its kind. There are ample records documenting the formal presentation of Medals of Honor almost from the medal’s inception. One such account can be found in the Army and Navy Journal, Jan. 25, 1873, page 374:

Quite an interesting occurrence took place at this post yesterday evening, when, in the presence of the whole command on dress parade, medals of honor were presented to First Sergeant Wilson, Corporal Pratt, and Blacksmith Branigan, all of Company I, Fourth Cavalry, for bravery displayed in the fight with Comanche Indians last September, on the North Fork of Red river, under General Mackenzie’s command. The men having been ordered to the front by the post adjutant, the three men advanced to within a few paces of him, when each in his turn was handed a medal, and from their appearance as they faced about to return to the ranks, it was evident they felt proud of the mark of distinction conferred upon them. Fame is as dear to the soldier of a republic as of an empire, even to a soldier of the most ordinary intelligence in the ranks, and the awarding of these medals to men who have proved their courage above their fellows is but right and proper, and must, without doubt, be an incentive to good conduct, and a most powerful adjunct in elevating the tone of the enlisted men in the Army.

Citation for this article: Samuel L. Russell, “First Sergeant Frederick Ernest Toy, G Troop, 7th Cavalry – Conspicuous Bravery and Coolness in Action,” Army at Wounded Knee (Savannah, GA: Russell Martial Research, 2017-2018), https://wp.me/p3NoJy-1DC posted 11 Apr 2018, accessed _______.

Sam— Can you please send this post to me again? Beyond this page, I’m having trouble printing it out for unknown reasons. Thanks, Jerry

>

LikeLike

Sir,

If you would please contact me, I have some information regarding Otto Voit, 7th Cavalry. My e-mail is below.

4kk.miknahallac@gmail.com

Sincerely,

Kim Callahan

LikeLike