I told him that I did not want to see one soldier killed or one Indian killed either. That the soldiers did not want to kill any Indians unless they were compelled to.

–Mr. John Dunn, cattle rancher

Colonel Edwin V. Sumner, Jr., was under great scrutiny in the last week of December 1890 after Big Foot had eluded surrendering to the cavalry colonel and slipped away the night of December 23, ostensibly to combine forces with Short Bull and Kicking Bear in the stronghold of the Bad Lands. Sumner was receiving the brunt of Major General Nelson A. Miles’s ire for what the commanding general viewed as inept, disobeyance of orders to capture and disarm Big Foot’s band. The following message from General Miles’s aide to Colonel Henry C. Merriam, commander of the 7th Infantry Regiment, expressed the general’s disappointment with Sumner.

Maus to Commander, Fort Bennett, S.D. (Dec 27): Forward this without delay to Colonel Merriam:

The Division Commander directs you move up Cheyenne River far enough to communicate with Colonel Sumner and assume command of that line. Colonel Sumner has been directed to report to you for orders.

The Division Commander is much embarrassed that Big Foot allowed to escape and directs you to use the force under your command to recapture him. He has his own 60 lodges, 38 men from Standing Rock and had 30 runaways from Hump’s band. It was believed he was near the Bad Lands and not far from Pine Ridge yesterday, but may double back and go near his own village, moving at night and concealing his people in the daytime. You can do the same with your force or take such action as you deem best to accomplish the object.

By command of Major General Miles.[1]

Initially Sumner felt he had been deceived by the duplicitous and malign actions of a local rancher named John Dunn. Writing to Colonel Merriam, Sumner laid blame on Dunn for interfering with the plans to bring Big Foot to Fort Bennett by convincing the Miniconjou chief to flee to the stronghold instead.

Sumner to Merriam (Dec 27): Big Foot and his band left their village on the night of the 23rd and went to the Bad Lands. I had scouts in his camp who came and told me the Indians were packing up to go to Bennett next morning, and I expected to take them down and turn them over to you. A white man by the name of Dunn, however, got into their camp and told them I was on the road to attack and kill them all, and of your command down the river so they just stampeded and like rabbits fled for shelter in the Bad Lands, carrying nothing and traveling so fast I could not overtake them.[2]

Colonel Sumner did not mention to Colonel Merriam that Dunn went to Big Foot at Sumner’s request. In his statement of February 3, 1891, regarding the flight of Big Foot’s band, Sumner stated that, “I was at one time inclined to believe that Mr. Dunn had played me false, but he is a man of good reputation, and from his statement and statements of officers who have seen and interviewed him since, I am now sure that I did him an injustice, and I do not believe or claim that Mr. Dunn was in any way responsible for events which afterwards occurred.”[3]

Colonel Sumner’s February 3 statement was provided at the request of Colonel Edward M. Heyl, General Miles’s inspector general, who was investigating possible charges against Sumner. To support his defense, Sumner requested that Mr. Dunn provide a statement regarding his role in Big Foot’s flight.

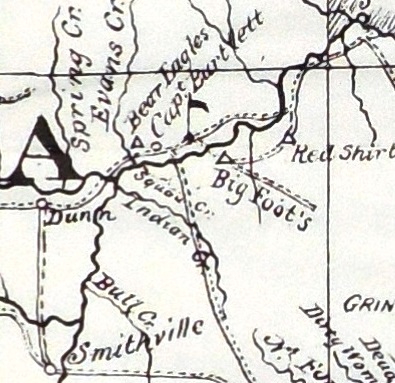

Inset is cropped from Brigadier General John R. Brooke’s campaign map and depicts Camp Cheyenne–the black flag–across the river from Big Foot’s village. Dunn’s ranch is depicted to the west just beneath the large letter ‘A.'[4]

John Dunn was a forty-one-year-old cattle rancher living on the Belle Fourche fork of the Cheyenne River, a few miles from Big Foot’s village and Colonel Sumner’s camp. He was a native New Yorker and the son of Irish immigrants. He had been in the area of Big Foot’s village for almost a decade, was known to the local Miniconjou band, and spoke their language. Following is the statement he provided Colonel Sumner.

Dunn’s statement (Jan 17, 1891). I came to Col. Sumner’s camp on Tuesday, December 23, 1890, to sell some butter. I went up to Capt. Hennisee to tell him that there was a Corp. Bradley camped upon the creek and wanted to know if he wanted to send him any message. Capt. Hennisee told me that the colonel wanted to see me; the colonel was eating dinner and I waited until he had finished. When the colonel came out he said he wanted to see me for quite awhile, and I told him I had been to the camp on Sunday but he was not there. He told me he would hire me if I wanted to. I told him it was not possible as I could not go, and he said all right. He asked me if I would go down to Big Foot’s camp for him. I told him I would not go, as my wife was alone at home and would not know where I was. He asked me if I would not go down, as I was well acquainted with him [Big Foot], and try to get him to go to Fort Bennett. I refused three times before I went, and then consented to go. The colonel told me to ask Big Foot why he had not come to camp that day as he promised, as he thought he was a man of his word. The colonel said he did not know how far he would go down, but he would go four or five miles anyhow.

He told me to tell Big Foot as long as he would not come up that he would send ten or fifteen soldiers with him to Fort Bennett. Felix Benoit, half-breed interpreter, came along with me. Benoit stopped about one-half mile from Big Foot’s camp to fix his saddle. I went on up to the village alone. An Indian, called the “Important Man,” belonging to Bear Eagle’s band, came up and shook hands with me. I asked him where Big Foot’s house was. He showed me where the house was, and I tied my horse to a wagon outside Big Foot’s house, with some hay and tepee poles on top of the hay. I asked the Important Man where the wagons were going to (there were several with a small quantity of hay and tepee poles on top). He told me they were going to Fort Bennett. I went into Big Foot’s house and met his squaw about 4 feet from the door. She shook hands with me and told me to go in. As I went in I saw Big Foot lying on the bed. He got up and shook hands. Several Indians followed me in the house. I told Big Foot I came over to the soldiers’ camp to-day between 12 and 1 o’clock to sell some butter. I told him the commanding officer asked me to come down and see him; the commanding officer told me to ask him why he did not come up to his camp to-day as he promised, and that he thought he was a man of his word. He said he had been sick and felt bad all day. I told him as long as he had not come up the commanding officer wanted to know if he would not go down to Fort Bennett. He asked why he had not taken him down there when he had him down near Cherry Creek before. I told him that I did not know; was not there, and I knew nothing about it. I told him that I did not want to see one soldier killed or one Indian killed either. That the soldiers did not want to kill any Indians unless they were compelled to. I told him I had to go about 20 miles, and as it was near sundown I wanted to know what he wanted to say to the colonel, as I was in a hurry. He said that he would go to Fort Bennett in the morning. The colonel said he would send a small detachment of soldiers to escort them along. He told me he did not want to fight. I told him I was very glad to hear him say so, for when fighting commenced there is no telling when it will stop. I asked him if the Indians from Standing Rock were still at his village; that the colonel wanted to know. He said they were. Then Felix Benoit, the interpreter, came in. I told Benoit the Indians seemed all quiet and said they were going to Fort Bennett. I told Benoit to ask the Indians what I had said to them and find out all I had said. Benoit asked me to stop a little longer; but as it was near sundown I told him I could not, as I had left my wife at home alone. I shook hands with Big Foot and a number of other Indians with whom I was acquainted and left, leaving Benoit in the house. I met the colonel at Bear Eagle’s village very near sundown. He asked me what success I had and how things were at the village. I said everything looked quiet and I did not think he would have to fire one shot. The colonel asked why he had not come up to-day and I told him he said he had been sick. The colonel asked me if he had agreed to go to Bennett, and I said he had, and that they would all go in the morning. I told the colonel what the colonel had said up at the camp, “that he would send ten or fifteen soldiers with them to Fort Bennett.” The colonel said: “They are afraid of me.” It was very dark and some of the soldiers asked the colonel if he had seen Bear Eagle. He said he did not, and called me back. He asked me to tell Bear Eagle that he wanted him to get his wagon ready, as he wanted him to start to Fort Bennett with him in the morning. He told me also to tell Bear Eagle that the troops were not there to hurt or kill any Indians. That he had received a letter from the Great Father at Washington that day telling him that all the Indians had to get out of that valley and go to the agency. That there were troops coming up from Cherry Creek and that any Indians found there would be considered hostile. I told Bear Eagle that Big Foot was also going to Fort Bennett with all his band in the morning; that he had just told me that he was. It seemed to surprise him and he looked up and wondered. The colonel took off his glove and shook hands with me, and said he was very thankful to me, and wanted to sign a voucher for me to pay for my trouble, but I refused it, saying that I would do anything to save blood.

Afterwards I met Serg. Moore less than a mile from camp. He asked me how everything was, and I said everything was quiet and that I did not think there would be any trouble whatever. I also told Mr. Frank Cuttle that I did not anticipate any trouble.

I have been among the Sioux for about twenty years, and have lived on the Belle Fourche for nine years. I speak the Sioux language and have known Big Foot for nine years, and until the last two or three months have seen him monthly for eight or nine years. When I went to Col. Sumner‘s camp on December 23, 1890, to sell butter I had not received any message from Big Foot or any other Indian. When I saw the colonel I told him that I did not think they meant to fight, as I had never known them to fight with the women and children present. I have here stated all to the best of my recollection that took place in my interview with Col. Sumner and with Big Foot. During a portion of the time I was talking to Col. Sumner several other officers were present. I told Col. Sumner that I heard Big Foot say time and again that he would sooner die than leave his village, and he said, “Then die it is.”

When I left Big Foot I had not the least doubt but that he would go to Fort Bennett. I had not the least suspicion that he and his band intended going south. My only explanation of his violation of his promise, that he thought he was going into a trap.[5]

For his defense, Colonel Sumner also obtained a statement from Felix Benoist. He was born in the Nebraska territory and was a thirty-one-year-old son of a French-Canadian trapper and a Lakota woman. As a teenager Benoist attended the Hampton Institute in Virginia in 1877 where he learned to read, write, and speak English. He served three six-month enlistments in the 20th Infantry regiment with a detachment of Indian Scouts in 1882, 1883, and 1884 at Fort Bennett. In 1890, he was a blacksmith at the Cheyenne River Agency and was serving as an interpreter for Sumner.[6]

Benoist’s statement (Jan 19, 1891). On the 23d of December, 1890, about noon, I was sent by Col. Sumner to Big Foot‘s camp, in company with Mr. John Dunn. When we got into camp Mr. Dunn was about 200 yards ahead of me. The Indian scouts, who had been sent down that morning to tell Big Foot to come up, were just leaving his camp to return to Col. Sumner‘s camp. I stopped and talked with them, and that is how Mr.Dunn got ahead of me. I asked the scouts why Big Foot did not come up to camp. They said that Big Foot told them that the Standing Rock Indians who had been with him the day before had gone away, and he did not want to go to Col. Summers’s [sic] camp without them. I told them to go back with me to Big Foot‘s house. When we got there I went inside with one of the scouts (His Horse Looking). When I got in the house was crowded with Big Foot‘s warriors or men, and John Dunn was standing right beside Big Foot, and Big Foot was calling out loud to the people so they all could hear it, saying, “I am ordered to go down to Bennett to-morrow morning, and,” he said, “we must all go to Bennett; if we don’t go, John Dunn is sent here to tell me that if we don’t go the soldiers will come here in the morning and make us go, and shoot us if they have to.” I did not hear John Dunn tell Big Foot this, but he was standing right there and did not deny or dispute it. Then John Dunn came out and came on home, and I stood in there with His Horse Looking, a scout. Big Foot asked me if Col. Dunn [sic: Sumner] had sent John Dunn to tell him this, and I told him yes; the colonel had sent Dunn to tell him that he must go to Bennett. Then His Horse Looking told me that the best way was to go in the morning, and all together, and Big Foot said he would. Then we came out of the camp, and when we were about a half a mile from Big Foot‘s house we saw the Indians gathering in the ponies, and remarked that they must be going to start, about half past 3 or 4 o’clock, but they had said they were all going to Bennett. Then we left one scout behind (Charging First) to see if they started that evening, and the rest of us came on to Col. Sumner‘s camp, which was about 5 miles west of Big Foot‘s village. About half an hour afterwards Charging First came in saying that the women and children were badly frightened, and he thought they were going to start for Bennett right away that evening. Then Col. Sumner sent three scouts (His Horse Looking, Charging First, and Iron Shield) to the village to tell Big Foot not to leave that evening, but that they must go in the morning, and that he wanted Big Foot to come up and see him next morning before they started. About an hour and a half after they started, two of them (His Horse Looking and Iron Shield) came back and said that a large party of the Indians had already started, and the others were getting ready to go. They had gone up Deep Creek, and the scouts did not know whether they were going to Bennett by the ridge road or going to the south, but Charging First had remained behind to find out which way they were going. The next morning (24th December) Charging First returned about 8 o’clock, and said he had ridden all night: that he had come up with the leading Indians, who were going south, near Davidson’s ranch, about 12 o’clock in the night, and stood there with them until they all caught up. Big Foot came up with the squaws. He had a talk with Big Foot there, who sent word by him to Col. Sumner that he (Big Foot) did not want to go south, and wanted to go to Bennett, but that [he] and his people were afraid that they would get into a trap if they went to Bennett, and that he was compelled to go to Pine Ridge, and he had to go. While he was talking to Big Foot about fifteen bucks rode up around them and told him (Charging First) that if it was any other scout except him they would kill him.[7]

Benoist’s statement that he heard Big Foot say, “John Dunn is sent here to tell me that if we don’t go the soldiers will come here in the morning and make us go, and shoot us if they have to,” indicated that perhaps Dunn had been a malign actor in providing false information to the Miniconjou chief in order to sway him to head to Pine Ridge instead. That certainly seems to be what Colonel Sumner initially thought.

More than fifteen years after Wounded Knee, Judge Eli S. Ricker conducted a series of interviews with Indians and settlers in the area in order to record the Lakota perspective of Wounded Knee. In his interview with Joseph Horn Cloud on October 23, 1906, Ricker recorded how Dunn’s message was received by the Lakota on that fateful day in which Big Foot headed south with his band.

On December 23 Joseph and William Horn Cloud went down the river for some hay. When they were loading an Indian rode up with a sweating and foaming horse and told them to hurry and get home; that some soldiers were coming to fight. The Horn Clouds did not believe him. He asked what they were going to do with the hay. He told them there was going to be a fight; still the boys did not believe him and kept at their work and loaded up their wagon. Coming home they met their brother Frank coming to them. He told them that a white man had come and told the Indians that a lot of troops were going to come to night or to-morrow night. Frank said that their father had sent him to tell them to hurry home. They hastened home as fast as they could with their hay. Leaving their load of hay when they got home, these two, leaving Frank with the parents and taking White Lance, another brother, the three rode over to Big Foot’s, about three miles. There they saw the white man that Frank had told them about, his horse still wet with sweat; he was telling the Indians that the troops would come to-night or to-morrow night, and that they should go to Pine Ridge, for there were more Indians there. But Big Foot refused. This man kept on telling them to run away. The Indians argued among themselves; some tried to persuade Big Foot to go, saying that this white man whose Christian name was John (can not give last name) and who they called Red Beard, was a friend to them and always had been, and he would not tell them anything but the truth. Big Foot continued his refusal, saying that he would not leave his home. Red Beard persisted in urging them to go, telling them that he did not want to see their women and children killed. Big Foot would not yield. He said: “This is my home; this is my place; if they want to kill me–if they want to do anything to me, let them come and do as they please. I don’t want to do anything wrong towards the white people.” Then Red Beard spoke and said “Red Fish,” addressing one of Big Foot’s men, “my friend (kola) if you want to defend yourselves you must remember your knives and your guns; do it like a man.” Some of the Indians still wanted to come to the Pine Ridge Reservation. Red Beard again spoke up: “I heard the officers agree together to bring a thousand soldiers from Fort Mead to take all the men and bring them to Fort Mead as prisoners.” He repeated this statement. He then said he was going to return to his ranch on the Belle Fourche by way of the soldiers’ camp, and told the Indians not to tell on him.[8]

Eli Ricker interviewed Joseph Horn Cloud’s older brother, Dewey Beard, on February 20, 1907. Beard was about twenty-eight years old at the Wounded Knee fight and had participated in the Little Big Horn fight when he was about fourteen. He did not speak English and his younger brother, Joseph, served as interpreter. Following is Beard’s account of John Dunn’s discussion with Big Foot.

Big Foot told the Horned Clouds to move up to his camp, which they did next day. While they were camped with B. F. somebody told me my duck (tent) was in the soldier camp & I went over to see if the tent was there. On the way I met a white man and an Indian on the road. Indian said: “You better go back home because this man wants to have a council with all these Indians.” He came back with them. Somebody hollered out for all the Indians to come together, for “this white man wants to tell you something.” All assembled round the white man who told things which I heard myself. The white man spoke as follows:

“My dear friends: I have come over to talk with you and tell you that the officers had a council last night and they have spoke or decided this way: All the officers talk that they will catch all the Indian men tonight (not the women) and take you over to the Fort Mead & then move them on an island in the ocean in the east. If you don’t want to give up the arms you can defend yourselves & do as you please.” The white man said he lived there and had a lot of cattle, & he was afraid that if there was war he was going to lose all his cattle; therefore he told them truly all the soldiers said; because I am a friend to all the Indians. Then he began to tell again. “There is going to be trouble over at Pine Ridge–they have already started the trouble; and you can go over there right away if you want to save your lives. If you don’t listen to me you will get into trouble; you didn’t listen to me before & got into trouble. I want you to go to Pine Ridge.” The Inds. called this white man Red Beard.[9]

These statements from Felix Benoist, Joseph Horn Cloud, and Dewey Beard indicate that perhaps Colonel Sumner’s initial concerns regarding Dunn’s duplicitous nature was correct. Perhaps Sumner, in his report of February 3, 1891, presented Dunn as a more upright, concerned citizen in order to lend credibility to a statement that tended to support Sumner’s position. Such a position would bode better for Sumner than the notion that he himself sent the man who played the role of agitator and malign actor.

Historians have weighed these statements and viewed Dunn as a catalyst who provoked Big Foot’s band into fleeing south rather than going into Fort Bennett.

Utley stated, “I accept Benoit’s version as the more probable not only because of subsequent events but also because both Dewey Beard and Joseph Horn Cloud, who were present, remembered that ‘Red Beard’ had warned that the soldiers would shoot if not obeyed.” Jensen wrote, “It was Dunn’s story that set the band on the road to Wounded Knee.” Richardson equivocated, “Exactly what Dunn told Big Foot’s people next is not clear. Either Dunn threatened them to get them to move quickly or the Minneconjous were so afraid of the soldiers they misheard his information about the escort.” Greene presented a view that Dunn’s involvement merely reinforced events that were already driving some of Big Foot’s band to want to flee to the south, “My opinion is that the advance of Col. Merriam up the Cheyenne River and the report that the Standing Rock Indians at Bennett had been disarmed caused a sudden change of plan in Big Foot’s village, and that the young men, on account of the situation, were able to overcome all objections to going south.” Grua reinforced this notion writing, “Big Foot was initially reluctant to leave his home or make a movement that would alarm the soldiers. However, a local rancher named John Dunn… warned Big Foot… that troops intended to arrest his warriors and remove them from the reservation. With his warriors intent on fleeing to Pine Ridge, the chief conceded.”[10]

John Dunn remained in South Dakota for the rest of his life. The wife he mentioned in his statement was Catherine E. Hicks, whom he married in 1888. She died in 1894, and he later married a young girl named Blanche Adelia Louden while living in Haakon County, likely still at his ranch on the Belle Fourche. His second marriage ended in divorce and he moved to Meade County, South Dakota, where he was a farmer and claimed to be a widower, perhaps from his first marriage. Dunn died in 1922 and was buried in Sturgis, South Dakota.[11]

Felix Benoist and Cora Poor Bear, circa 1890.[14]

Judge Eli S. Ricker’s interviews have proven invaluable in shedding light on the Lakota version of the events surrounding Wounded Knee. Unfortunately, Ricker did not interview John Dunn or Felix Benoist. Such interviews may have provided more detail on what occurred at Big Foot’s village on December 23, 1890, that led to the band fleeing south toward Pine Ridge, and may have helped determine if John Dunn was just a concerned citizen or an agitator.

Endnotes:

[1] Henry C. Merriam, Exhibit G to Brig. Gen. Thomas H. Ruger’s “Report of Operations Relative to the Sioux Indians in 1890 and 1891,” in Report of the Secretary of War; being part of the Message and Documents Communicated to the Two Houses of Congress at the beginning of the First Session of the Fifty-Second Congress, vol. 1, by Redfield Proctor (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1892), 212.

[2] Ibid, 210-211.

[3] Edwin Vose Sumner Jr., Exhibit H to Ruger’s “Report of Operations Relative to the Sioux Indians in 1890 and 1891,” , 226.

[4] William F. Kelley, Pine Ridge 1890: An Eye Witness Account of the Events Surrounding the Fighting at Wounded Knee, edited and compiled by Alexander Kelley & Pierre Bovis (San Francisco: Pierre Bovis, 1971), cropped from fold out map attached to back of book. Hereafter cited as Brooke Campaign Map.

[5] Sumner, Exhibit H, 235-237.

[6] Donovin Sprague, Ziebach County: 1910-2010, Image of America series (Chicago: Arcadia Publishing 2010), 91; Ancestry.com, U.S. Army, Register of Enlistments, 1798-1914 (Provo: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007) Years: 1878-1914, Indian Scouts, image 259; National Archives and Records Administration, U.S., Civil War Pension Index: General Index to Pension Files, 1861-1934 (Provo: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2000); Ancestry.com. U.S., Register of Civil, Military, and Naval Service, 1863-1959, vol. 1 (Provo: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014), 700.

[7] Sumner, Exhibit H, 237-238.

[8] Eli S. Ricker, Voices of the American West: The Indian Interviews of Eli S. Ricker, 1903-1919, vol. 1, ed. by Richard E. Jensen (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005), 194-195.

[9] Ibid, 212-213.

[10] Robert M. Utley, Last Days of the Sioux Nation (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1971), 183; Richard E. Jensen, R. Eli Paul, and John E. Carter, Eyewitness at Wounded Knee (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press), 18; Heather Cox Richardson, Wounded Knee: Party Politics and the Road to an American Massacre (New York: Basic Books, 2010), 253; Jerome A. Greene, American Carnage: Wounded Knee, 1890 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2014), 201; David W. Grua, Surviving Wounded Knee: The Lakotas and the Politics of Memory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), 122.

[11] Pioneer Club of Western South Dakota, Pioneers of the open range: Haakon County, South Dakota Settlers Before January 1, 1906, (Midland: Pioneer Club of Western South Dakota, 1965), 112 and 118; Ancestry.com, United States Federal Census (Provo: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2006), Year: 1910, Census Place: School District 70, Meade, South Dakota, Roll: T624_1485, Page: 8A; Enumeration District: 0072, FHL microfilm: 1375498; Year: 1920, Census Place: Township 5, Meade, South Dakota; Roll: T625_1723, Page: 5A; Enumeration District: 134, Image: 605; Ancestry.com, South Dakota, Death Index, 1879-1955 (Provo: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2004), Certificate Number: 81137, Page: 235.

[12] BlackHillsFam, photo., “John Dunn,” FindAGrave (https://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=72068079) uploaded 23 Oct 2011, accessed 4 Jun 2017.

[13] Ancestry.com, United States Federal Census (Provo: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2004), Year: 1900, Census Place: Cheyenne River Indian Reservation, Dewey, South Dakota, Roll: 1555, Page: 38A, Enumeration District: 0048, FHL microfilm: 1241555; Year: 1910, Census Place: Cheyenne River Indian Reservation, Armstrong, South Dakota, Roll: T624_1475, Page: 2A, Enumeration District: 0117, FHL microfilm: 1375488; Year: 1920, Census Place: Cheyenne River Indian Reservation, Ziebach, South Dakota, Roll: T625_1726, Page: 3B, Enumeration District: 223, Image: 1132; Department of the Interior, U.S., Register of Civil, Military, and Naval Service, vol.1, (Washington, Government Printing Office, 1895), Year: 1885, Page: 519; Year: 1891, Page: 700; Year: 1895, Page: 739; Year: 1901, Page: 955; Ancestry.com, South Dakota, Death Index, 1879-1955, Certificate Number: 127319, Page: 67.

[14] sjwilson77, photo., “Felix Benoist and Mary ‘Virgin’ Poor Bear,” Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/mediaui-viewer/collection/1030/tree/55143505/person/26146782914/media/f66e42aa-f727-43b6-8556-4a4b5bcf1283?_phsrc=jGx1026&usePUBJs=true) uploaded 26 Aug 2012, accessed 4 Jun 2017.

Citation for this article: Samuel L. Russell, “John Dunn, Concerned Citizen or Agitator,” Army at Wounded Knee (Carlisle, PA: Russell Martial Research, 2015-2017), https://wp.me/p3NoJy-1DC updated 12 Apr 2018, accessed _______.

An excellent post. Really gives the flavor of the missteps, miscalculations, mistrust, and intrigues that led to the tragedy of Wounded Knee.

above

LikeLiked by 1 person

This post was updated on 12 Apr 2018 to include the details of John Dunn’s first wife whom he mentions in this statement.

John Dunn’s first wife was Catherine E. Hicks. They were married on January 1, 1888, at Viewfield, Dakota Territory. She was born at Horse Creek, North Carolina, on January 17, 1856, and was the third of seven children born to William Hicks and Keziah Rose Mahala. Her mother was half Cherokee. Keziah seems to have moved to the Dakota Territory sometime during the 1880s with some of her children. Catherine was the sister of Jim Hicks who was tried, convicted, and executed for the murder of John Henry Meyer in 1894. John Dunn testified at the trial. Catherine Hicks Dunn died in 1894, the same year her brother was executed. She is buried in the Elm Springs Cemetery, Meade County, South Dakota.

LikeLike