The Camp of Observation on the Cheyenne River

Adapted from remarks delivered by

Colonel Samuel L. Russell, U.S. Army retired

to the Order of the Indian Wars Annual Assembly

at Rapid City, South Dakota, September 5, 2024

“Big Foot advi[sed that] no one enlist as scouts that they continue [dan]cing and if interfered with in their religious meetings to fight.”

—Capt. A. G. Hennisee, 8th Cav.

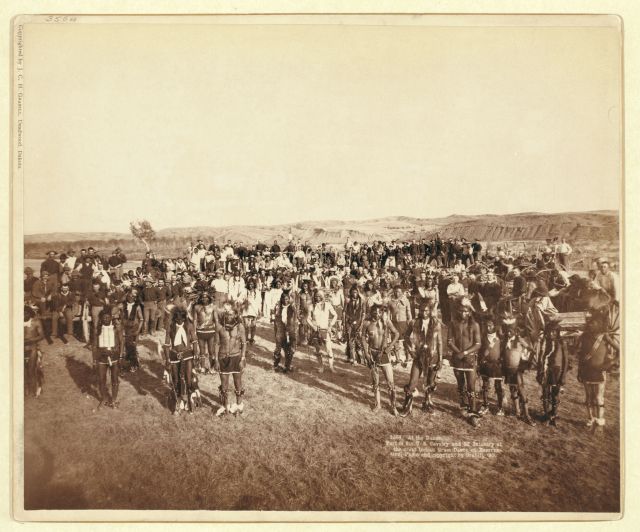

In August of 1890, five months before a single shot initiated the tragedy at Wounded Knee that annihilated Big Foot’s band of Miniconjou Lakota, those same Indians performed a ceremonial grass dance near their village on the Cheyenne River. The audience for these festivities included soldiers from the 3rd U.S. Infantry and 8th U.S. Cavalry regiments. The moment was captured by a young photographer from Deadwood, S. Dak., John C. H. Grabill. The Cheyenne River Indians had not yet been indoctrinated with the new Indian religion and its associated Ghost Dance that was spreading rapidly throughout the reservations across the western frontier. The photo is a haunting reflection, knowing most of the Indians pictured would be killed before the end of 1890. Grabill’s photograph prompts a number of questions, such as, why were the soldiers there months before the events that led to that winter’s campaign in the Dakotas, and what might they have seen that could shed light on this ill-fated band. The correspondence from a camp of observation that the Department of Dakota established on the Cheyenne River in the spring of 1890 provides answers to these questions and more. Those observations, recorded by a cavalry officer, have remained buried in the National Archives, unseen and never analyzed by Wounded Knee scholars and historians. Portions of those observations are recorded here for the first time.

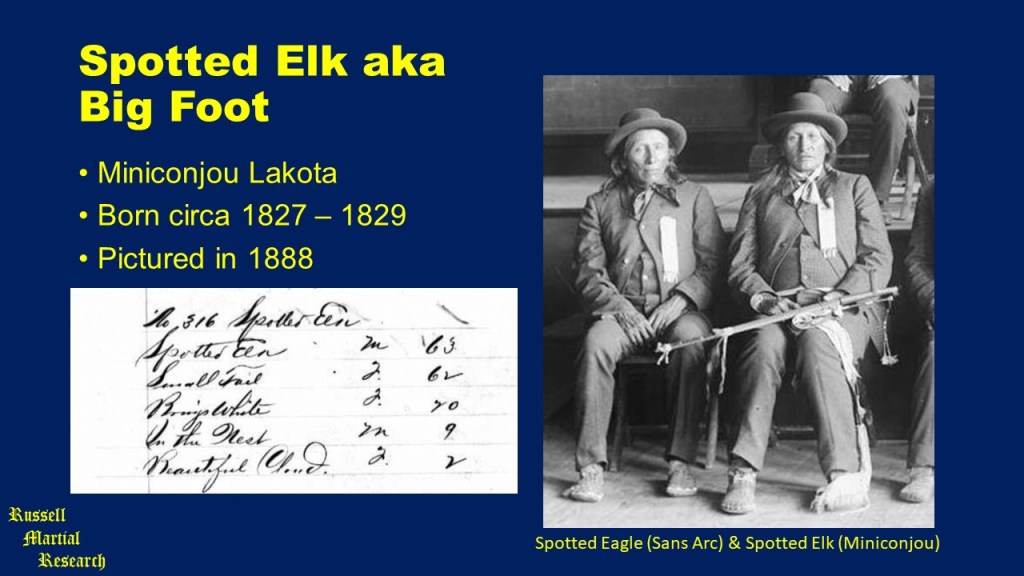

Before looking at the camp of observation, it is necessary to examine Spotted Elk, or Big Foot, as he was known to the soldiers and eventually to history. Pictured on the right is the most reliable photograph of Big Foot. He is seated holding a peace pipe in his lap while attending an 1888 peace conference in Washington, D.C., as a member of the Chyenne River delegation representing the Miniconjou subdivision of the Lakota. According to the 1890 Indian census, Big Foot, listed by the name Spotted Elk, was 63 years of age. In his household were three women, 62-year-old Small Tail, 20-year-old Brings White, and two-year-old Beautiful Cloud, and a young boy, nine-year-old In the Nest. Regarding the methodology of taking the census, Cheyenne River Indian Agent Charles E. McChesney caveated that the census “was taken as carefully and accurately as possible with the force available for the work on July 7, 8, and 9, 1890, that being the most practicable time, as all the Indians (except the infirm and those left to care for the camps) were then assembled at the agency.”1

Big Foot was a Miniconjou chief who had surrendered during the Great Sioux War in 1877 at the Cheyenne River Agency. He established a village on the Cheyenne River about 1882, and his band resided at that location from that time. Chief Big Foot, like Sitting Bull, was vehemently opposed to signing the Sioux Agreement of 1889 that ceded “9,274,668.7 acres, leaving to the Teton and Yanktonai tribes only 12,681,911 acres within the boundaries of the Cheyenne River, Crow Creek, Lower Brule, Pine Ridge, Rosebud, and Standing Rock reservations.” McChesney had been the Indian agent at Cheyenne River Agency since 1886, and based on Big Foot’s opposition to the treaty, McChesney wrote in March 1890 to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs recommending that a military presence near Big Foot’s village would be necessary to protect survey parties that were expected to mark ceded lands and settlers looking for land to graze and farm. It was this request that led Brig. Gen. Thomas H. Ruger, Commander of the Department of Dakota, to establish a temporary camp of observation on the Cheyenne River in April 1890.2

The officer charged with establishing the camp and reporting on his observations was 51-year-old Captain Argalus G. Hennisee, the third most senior of twelve captains in the 8th U.S. Cavalry Regiment. He was an experienced cavalry officer and Civil War veteran, having served as a lieutenant and later captain of the First Maryland Volunteer Infantry from July 1862 until mustered out of service in 1865. Hennisee was appointed a second lieutenant of infantry at the beginning of 1867, promoted to first lieutenant the following year, and transferred to the cavalry in 1871. He served as Indian Agent to the Mescalero and later Southern Apaches in the early 1870s. Hennisee was promoted to captain of I troop, 8th Cavalry, in 1881. For the 1890 camp of observation mission, Hennisee was given command of a battalion consisting of three troops from the 8th Cavalry and two companies from the 3rd Infantry.3

Big Foot’s village was located below or east of the junction of the Cheyenne River and Belle Fourche outside of the newly designated boundaries of the Cheyenne River Reservation making that land potentially available for settlement provided the Indians moved onto the reservation. This dynamic drove Agent McChesney’s decision to request the military establish a camp of observation. Depicted on the inset of Brig. Gen. John R. Brooke’s 1890 campaign map is the location of Big Foot’s village, and the proximate location of Captain Hennisee’s camp, shown by the guidon icon. Following is Captain Hennisee’s first report dated 8 April 1890 as he moved down the Cheyenne River to find a suitable location for the camp.

I arrived here with three troops of cavalry and two companies of infantry from Fort Meade, S. Dak. today. I find the Indians are living along both banks of the Cheyenne River, commencing at two miles below the junction and extending to about the reservation proper—they number about 1000 men, women and children as near as I can estimate them. The principal men are ‘Big Foot’ or ‘Spotted Elk’, ‘Bear Eagle’ and ‘Red Shirt’ with the[ir] people. I have had a talk with ‘Bear Eagle’ and he seems thoroughly dissatisfied.4

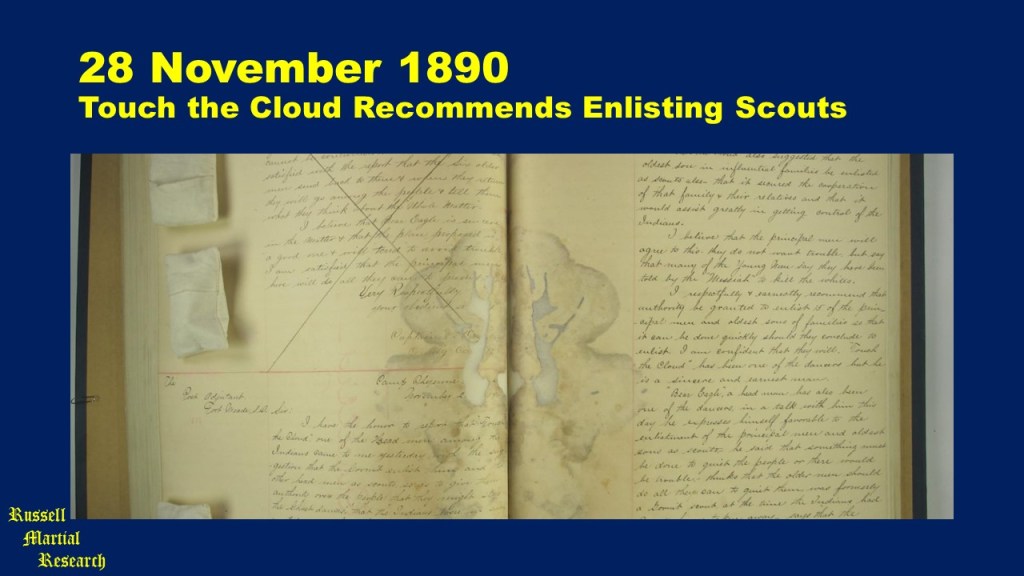

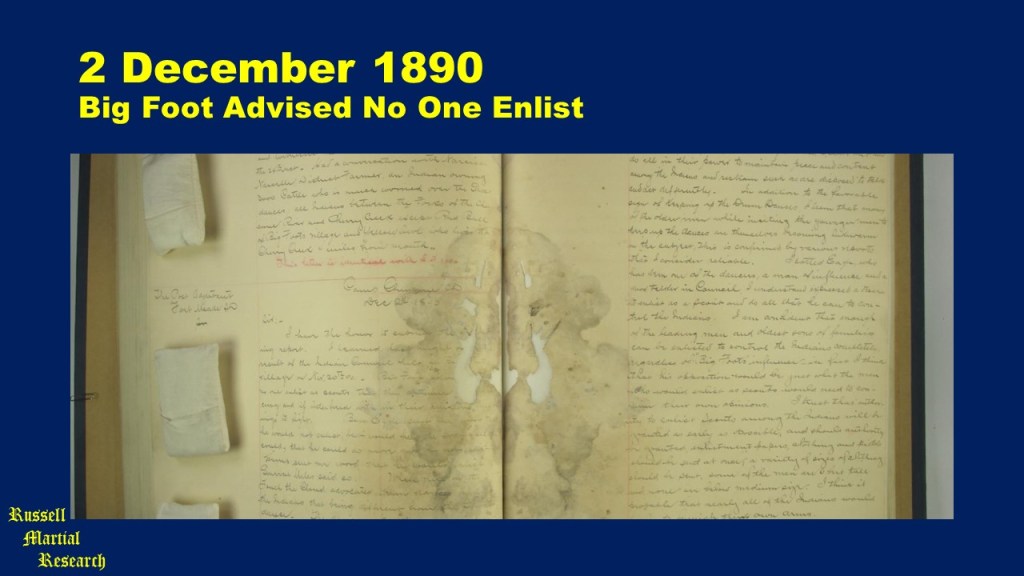

Each military post, whether a permanent fort or a temporary field camp, was required to maintain records pertinent to that post. The observations or reports contained in this essay come from the ‘Letters Sent’ file for the Camp on Cheyenne River. They are contained in one logbook consisting of over 200 letters spanning 164 pages. In the book are certified copies of every letter sent by the post’s commander or adjutant on behalf of the commander. The letters date from 7 April 1890 to 22 February 1891. Most of the letters are signed by Captain Hennisee for the first eight months, up to the point that Lt. Col. Edwin V. Sumner, Jr., also of the 8th Cavalry, assumed command of the post in the first week of December 1890 as events of that winter campaign began to escalate. The majority of the letters deal with the day-to-day administration of operating a camp in the field. Presented here are fourteen of the letters that deal specifically with Big Foot’s band or relevant events regarding the Indians who lived along the Cheyenne River off of the reservation proper.5 All of these letters were signed by Capt. Hennisee, and, unless stated otherwise, were sent to his higher headquarters at Fort Meade, S. Dak. The log itself has undergone extensive deterioration in 130 years, likely having been subjected to moisture at some point in the archives. Presented here and on subsequent slides are images of the actual pages from the log of each of the letters presented. Much of the pages are unreadable with portions of the pages missing. I have made the best possible transcription of each page, but some of the text in the log are lost to history. These letters are significant because they are not otherwise contained in the National Archives compilation of correspondence related to the Wounded Knee investigation and the Sioux Campaign of 1890-1891.

Upon establishing his temporary camp on 8 April, Capt. Hennisee reported the following. It is important to note that from the beginning of the observation mission, Hennisee was detailing the potential arrest or removal of some or all of the Indians.

Camp on Cheyenne River, 9 miles below junction of Cheyenne & Belle Fourche, S. Dak.

The obstinate and obstreperous Indians can be arrested individually by the Indian Police without [and in absence] of Troops, and taken to the Agency & confined.

If these Indians are to be removed by force, which I do not think advisable as they have lived here peaceably for years, it should not be attempted with less than 500 troopers.I have at this camp: 9 Commissioned Officers, 1 A. A. Surgeon, 212 Enlisted Soldiers, 150 Horses, 58 Mules, 9 six-mule-wagons, 1 four-mule-hospital-ambulance.

About a week into his mission, Capt. Hennisee reported specifically on the temperament of Big Foot, based not on his observations but those of Agent McChesney. 15 April 1890:

After the fifth days march the troops went into temporary camp on the North Bank of the Cheyenne River, eight miles below the junction of the Belle Fourche and in the vicinity of the largest band of Indians belonging to the Cheyenne River Agency now living outside the limits of the reservation—about one mile from the camp of ‘Big Foot’ or ‘Spotted Elk’ who is reported by the agent at Cheyenne River Agency as the most troublesome Indian belonging to his agency—he is principal chief of all living off the reservation.

The chiefs reported to me the number of people in their respective villages as follows. ‘Big Foot’ or ‘Spotted Elk’ with 220 men, women and children, village consists of 26 log homes, 18 tepis and 1 domed house. ‘Bear Eagle’ with 90….’Red Shirt’ with 20….’Touch the Cloud’ with 63….Total 396 people 68 homes and 30 tepis. In my first letter I reported the number to be about 1000—396 is about the correct number.

There are no white settlers in Cheyenne River Valley on the land lately ceded and although the valley, generally about a half mile wide, contains some good lands that might be irrigated, I doubt if any person will desire to settle here until the Indians have decided about taking the land they now live on—I understand that they have until March 31, 1891 to decide.

There is an abundance of land for these Indians on the reservation and of much better quality, but they don’t want to give up their houses here, I have had frequent talks with these Indians, many of them are in camp daily.

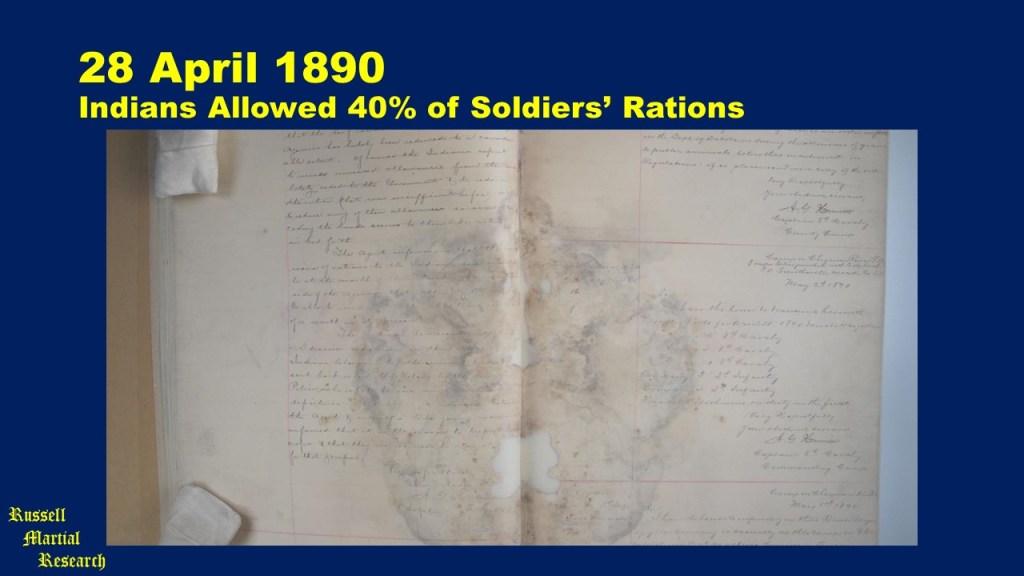

In his 28 April 1890 report, Capt. Hennisee commented on the scant rations provided by treaty to the Indians.

Agt. C. E. McChesney in charge of the Cheyenne R. Agency visited the camp on the 25th inst. From him I learned that these Indians are allowed about forty percent of a soldier’s ration for each person including children—that number in the valley living off the new reservation is 365, including children—this would make the number, 396, reported by me about correct, as there were increases…present belonging to other agencies that do not, at present, receive rations at the Cheyenne R. Agency….From Agent McChesney, I learn that the beef ration at Rosebud and Pine Ridge Agencies has lately been reduced to a considerable extent. Of course the Indians expect to receive increased allowances from the land they ceded to the Government & to retain the ration (that was insufficient before) and to reduce any of their allowances so soon after ceding the lands seems to them like acting in bad faith.

Based now on his own observations, Capt. Hennisee reported on 14 July 1890 that “‘Big Foot’ objects to almost anything that the Government wants the Indians to do.”

Not more than ten wagons with settlers have passed West through the Cheyenne River valley—none have wanted to take land here. The attitude of the Indians toward all has been friendly. Toward one party that undertook to come with a lot of cattle—the Indians wanted one lot for beef… and acted in a threatening manner toward this party of settlers—prevented them from passing through the valley. They finally went back to… Smithville and reported to me by letter… Big Foot acknowledged to me afterwards that he wanted them to give the Indians beef for passing through their country….I told the Indians very plainly that they should not interfere with the strangers under any circumstances, that they should render them assistance wherever necessary. ‘Big Foot’ objects to almost anything that the Government wants the Indians to do—wants to remain on this land without taking it individually and will do all that he dare do to this end….

The Indians are not in good condition to resist any action that the Government decides to take. Agent McChesney…wrote me June 29th ’90, “From present indications…have very little for the Indians in the way of rations next issue day—Congress has not passed the Indian appropriation bill, and unless it does so in the next few days nothing can be purchased. We have no beef, sugar, coffee or flour as all were issued last ration day….I have a small quantity of Bacon and Beans and very little corn meal and will issue all I have in the hopes that Congress will come to the rescue in time to prevent starvation.”

On 1 August 1890, Capt. Hennisee responded to a Department of Dakota request for information on the ability to recruit Indians to serve as scouts.

In reply to your letter of July 25 asking if some good material for scouts…from among Big Foot’s followers…about fifteen men can be found among these Indians who would make excellent scouts and would prove [loyal] to the Government—if necessary and [more] can be found further east nearer the agency. I have seen no vicious Indians here—they are well disposed and were it not for the influence of Big Foot over them I think that most of them would be willing to go on the Reservation. The only way to destroy Big Foot’s influences is to take away his liberty for a time—while he is at large he will probably give us less trouble here than he would on the Reservation where there are more Indians to listen to his talk.

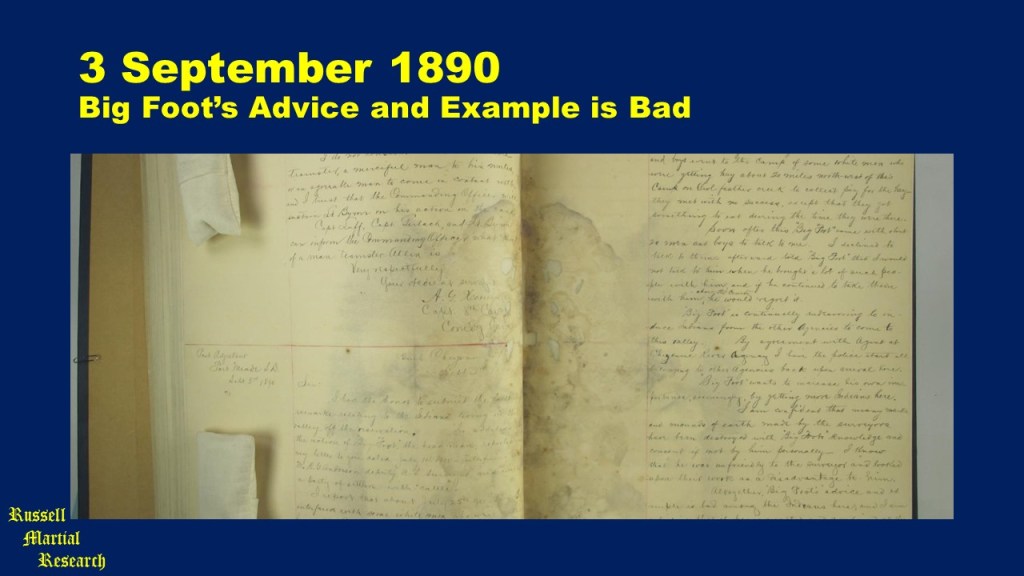

Capt. Hennisee’s 3 September 1890 report included examples of Big Foot’s apparent malign actions, although none rise to the level of depredations.

In addition to the action of ‘Big Foot,’ the head man, reported in my letter to you dated July 14, 1890—interfering with Mr. R. G. Anderson, deputy U.S. Surveyor, and with a party of settlers with cattle. I report that about July 25th ‘90 ‘Big Foot’ interfered with some white men who were getting hay on the East side of the Cheyenne River about four miles above the junction with the Belle Fourche, not on land claimed by the Indians; he took with him about 20 men and boys and endeavored to collect pay for cutting the hay, by intimidating; some of the parties gave the Indians a pig and calf, one of the men refused to give them anything, and he and ‘Big Foot’ called each other names as best they could, neither understanding the language of the other to any extent. I talked with ‘Big Foot’ about this matter and he acknowledged to have done as stated.

About Aug. 3rd ‘90, ‘Big Foot’ with about 20 men and boys went to camp of some white men who were getting hay about 20 miles north-west of this Camp on Owl-Feather creek to collect pay for the hay—they met with no success, except that they got something to eat during the time they were there.

Soon after this ‘Big Foot’ came with about 20 men and boys to talk to me. I declined to talk to them—afterward told ‘Big Foot’ that I would not talk to him when he brought a lot of such people with him and if he continued to take them with him about the country he would regret it.

‘Big Foot’ is continually endeavoring to induce Indians from the other Agencies to come to this valley. By agreement with Agent at Cheyenne River Agency I have the police start all belonging to other Agencies back upon arrival here.

‘Big Foot’ wants to increase his own importance, seemingly, by getting more Indians here. I am confident that many marks and mounds of earth made by the surveyors have been destroyed with ‘Big Foot’s’ knowledge and consent if not by him personally. I know that he was unfriendly to the surveyor and looked upon their work as a disadvantage to him.

Altogether, ‘Big Foot’s’ advice and example is bad among the Indians here, and I am satisfied that if he is arrested and confined at the agency many of the Indians here will go on the new reservation before cold weather….

I am satisfied that it would be the interest of the Gov’t and the other Indians here to have ‘Big Foot’ and ‘Bear Eagle’ arrested by the Indian police and confined or detained at the Agency until after these Indians go on the new reservation, or take land individually where they now live, and I respectfully and urgently recommend such action.

On 10 September 1890, Capt. Hennisee wrote to Agent Perain P. Palmer, the new Indian Agent at Cheyenne River Agency who had taken over following Agent McChesney’s retirement, and detailed what clearly was the introduction of the Ghost Dance to the Chyenne River Indians from individuals from the Pine Ridge Agency.

U.S. Indian Agent, Cheyenne River Agency, Fort Bennet, S.D.

I have the honor to state that on the 8th inst. Policeman ‘Ree’ informed me that three Indian men and one woman belonging to Pine Ridge Agency were at ‘Big Foot’s’ village, without passes, that they had been sent away from the mouth of Cherry Creek a few days before, and were engaged in holding what they called Religious Meetings, and causing great excitement amongst the Indians. That these Indians had saddled their horses and promised to depart for Pine Ridge in the forenoon of that day, but late in the afternoon had not departed but were making preparation to hold further Religious meetings that night at ‘Big Foot’s’ village. Policeman ‘Ree’, John Black Hawk, Mixed with Food, and Charges Ahead, came to this Camp about sunset and wanted to start the three men and woman off that night for Pine Ridge—stated that they were not acting in good faith, and that there was no use in being patient with them; I told the Policemen that I thought it advisable to have them leave without further delay. The Policeman returned hurriedly to the village (about one and a quarter miles away) and told the strangers to get ready and leave at once—took their horses to them and after a time succeeded in getting them started in the direction of Pine Ridge Agency.Before the four Police returned to the village, considerable progress had been made in preparation for the Religious meetings, and there was considerable excitement among the Indians there. The four Policemen reported to me that night that they had met with considerable resistance in their efforts to have the parties leave for Pine Ridge, that ‘High Hawk’, ‘Black Wolf’, ‘Good Hawk’, ‘Iron Eyes’, ‘Boy’ and ‘Two Birds’ were the most active in the resistance. That ‘High Hawk’ led ‘Ree’s’ horse by the bridle rein into the center of the circle where the people where gathering, that ‘Black Wolf’ spoke of having a gun and ‘that he could use it, too’; he confessed to me that he went to his house and got his gun when he found that the Police wanted to break up the meeting.

‘Good Hawk’ informed me that he got his gun from his house and stood behind ‘Black Wolf’ when he spoke of having a gun. The others mentioned did not appear to take a very decisive part in the resistance….

The Chief of Police and Policeman ‘Thunder’ arrived here last night, the Captain of Police and others of the Police force arrived this morning and I had a talk with the six Indians accused of resisting the Police in the presence of the Police and about 100 of the Indian men living near here.

Each man confessed to have done about what the Policemen claimed he had done. They claimed the meeting (a religious one) was progress, and that the Police were excited, hasty manner[ed], and wanted the meeting broken up at once and were not disposed to be patient with any….

I talked over the whole matter with the Indians, told them that they were disposed to look at any action of the Police as unfriendly to them. That they were only trying to have the strangers who had been sent away from Cherry Creek and had promised to leave ‘Big Foot’s’ village in the afternoon, leave and go where they belonged; that, when they accomplished that object they left, leaving the meeting to go on, that my talk with them all was with a view of bringing about a better state of feeling between them. ‘Black Wolf’ is regarded among the Indians as insane. ‘Good Hawk’ is flighty, excitable, and almost insane at times, so Mr. Narcisse Narcelle informs me. ‘High Hawk’ is very impulsive and excitable….

The Indians promised to have no more of such meetings, said they were brought about by strangers from Pine Ridge, and asked me to write to the Agent at Pine Ridge to keep such people at home so that the Indians here will not be stirred up by them.

The names of the Parties from Pine Ridge are as follows: ‘Don’t Care for Anything’, ‘Red Feather’, ‘Prick’ and one woman, wife of ‘Don’t Care for Anything’. Will you please write to the Agent at Pine Ridge on the subject? Altogether, I think it may be well that the affair occurred. Such exciting meetings are seldom stopped so easily. I consider the need worth the cost.

Perhaps most significantly in this letter is Capt. Hennisee’s description of the principal Indian involved in the armed confrontation at the “religious meeting,” Black Wolf, who sounds similar to Black Coyote identified in the years and decades later by Dewey Beard as the Indian who fired the first shot at Wounded Knee. In the Lakota language, Coyote is Šuŋǧmanitu (shoon-gmah-nee-too) and Wolf is often referred to as Šuŋgmánitu Tȟáŋka (shoon-gmah-nee-too tawn-kah), which literally translates to “Big Coyote.” Moreover, neither the 1886 nor the 1890 Indian censuses for Cheyenne River list any family by the name of Black Coyote (or a coyote of any color for that matter), but there is one family with the name Black Wolf. It is possible that Hennisee’s Black Wolf is Dewey Beard’s Black Coyote.6

Capt. Hennisee recommended on 25 September that Big Foot be arrested by the Indian Police while at the Agency.

In reply to your inquiry of Sept. 17th relating to ‘Big Foot’ I have the honor to state that I believe that the Indian Police could and would effect his arrest and deliver him at the Agency without the assistance of troops. It would be better however to have it done at the Agency—he frequently goes there and would go at any time if required of the Agent. If he could be kept at or near the Agency, and treated well, without [being] confined I think the effect would be better. The principal object in the recommendation is to keep him away from the Indians here, for their benefit.

On 27 October 1890, Capt. Hennisee provided some interesting commentary in which he commended the “good conduct and integrity” of the Indians in comparison with the white settlers. He also recommended more Indian police and scouts and fewer soldiers.

I have the honor to submit the following remarks to the Petition from the Citizens of Meade County, S.D. for protection against the Sioux Indians: I am satisfied that the Indians in this vicinity will not disturb the White Settlers in Meade County during the coming Winter, and are not likely to do so at any future time unless provoked. The Indians have lived here about eight years. Some of the White settlers whose names are mentioned on this paper have lived at their present residence about four years and have had no trouble with the Indians….

The White settlers generally in the Eastern Part of Meade County do not speak well of each other. From my own observation since April 10th ‘90, I have quite as much faith in the good conduct and integrity of the Indians as I have of the White settlers. The Indians have behaved well. I have been surprised at their honesty, integrity and good faith in many instances; they have been some what stirred up lately by the Ghost dances or so called religious meetings that they have had.

I have had frequent talks with the head men about the exciting effect of such affairs but they told me that it was their form of worship of the Great God that the White men killed, that they meant no harm and did not injure any one but their selves. The presence of troops here this season has in my opinion had the effect of keeping the discontented Indians belonging to other Agencies from coming here. Big Foot, the head man here, is discontented and is not a good adviser. The Indians here are not regarded favorable by the other Indians, generally, belonging to the same agency, they are better satisfied, living apart from the others; and many of the discontented Indians of other agencies would naturally have come to this Valley during the summer had it not been for the presence of troops. No white settlers have attempted to settle in this part of the old reservation during the season of moderate temperature, and the cold season is too near now for any to come before next May. The Indian Police are good men and manage to keep the Indians under control without difficulty. They seldom have to exercise authority.

Should it be deemed necessary to keep troops in this vicinity, one discreet officer with ten selected Infantrymen with a four-mule-wagon, would probably serve the purpose. If necessary ten or more Indian Scouts could be enlisted to live among the Indians and observe their movements and disposition. Three Indian Police have been on duty here during the summer. I have recommended to the Agent an increase of the number to seven during the Winter and have been informed that he will endeavor to send them. The soldiers would control the Whites and the Indian scouts and Police [would] control the Indians….

Since arrival here April 5th ‘90, the Indian Police have managed every case requiring action among the Indians, the troops have taken no action whatever in any case. There are about fifteen Indians belonging to Big Foot’s band, who would make reliable and efficient scouts. The pay and allowances as scouts during the coming Winter would go very far toward their support, comfort and contentment would be beneficial to the Indians in many ways and be a judicious expenditure for the Government.

Capt. Hennisee reported 7 November 1890 to the Department of Dakota that Big Foot’s band had departed to the Black Hills on a hunt and that there had been only two “small” Ghost Dances over the past month.

Asst. Adjt. Gen., Dept. Dakota, St. Paul, Minn.

In reply to your letter of Oct 2[1] relating to the Indian Ghost Dances, etc., I have [this] to state that nearly all the Indians living at Big Foot’s village went hunting on Oct. 5th by permission of their Agent and, except two families, have not yet returned. [?] that the Agent gave so many hunting passes [?] with a view of breaking up the ‘Ghost Dances’ and it probably had the desired effect, as the two men who have returned report that the party, at the time they started back has killed 626 antelope, that the hunters were scattered over the country North of [the] Black Hills and East of the Little Missouri River….So the Indians are well provided with meat and skins for the coming Winter and they will [probably] be better contented on that account.I have heard of only two small ‘Ghost Dances’ within the last month in this Valley, one at ‘Bear Eagle’s’ and one at ‘Red Skirts’, both when the Police were away, and conducted in a very private manner. The Indians had a big Council amongst themselves at the Mouth of Cherry Creek last Sunday (2nd Inst.) and were informed by the Indian Police that they would be permitted to dance all day each Saturday in any manner that they pleased, but should they dance at any other time, the dancers would be arrested and taken to the Agency…. I do not believe that the ‘Ghost Dances’, or so called Religious Meetings will cause any trouble among the Indians—of course the dances have a tendency to excite them, but the Indians are peaceably disposed.

Capt. Hennisee on 19 November 1890, had to clear up with his higher headquarters some confusion on Big Foot’s whereabouts, as opposed to his band, that he detailed in his earlier letter to the department headquarters. He also detailed that the hunting party conducted Ghost Dances regularly while in the Black Hills.

I enclose copy of my report to the Dept. Commander dated Nov. 7th 1890. I did not say that ‘Big Foot’ was away on a hunting pass. He was at the Agency last to draw rations, and was frequently at this camp during the time the Indians were absent, hunting from Oct. 5th to Nov. 18th 1890.

The Agent did not inform me, in any manner, that he had given a large number of Indians permission to hunt. I learned through the Police on duty here that 23 families from ‘Big Foot’s’ Village had hunting passes upon which many more Indians went. The last of the Indians returned yesterday—they had a talk amongst themselves last night at ‘Bear Eagle’s’ Village. The talk was principally about the ‘Ghost Dances’. They concluded to keep them up. Nearly all the Indians, including the most substantial amongst them, seem affected with the craze; the hunting party had their dances every third night while on the hunt.

Capt. Hennisee reported on 26 November 1890 that the Indians at the ration issue on the reservation were armed with Winchester rifles with plenty of ammunition.

I have the honor to state that 2nd Lieut. E. W. Evans, 8th Cav. made a scout to Cherry Creek, witnessed the issue of rations to the Indians on the 24th, had a conversation with Narcesse Narcelle, District farmer, an Indian owning 300[0] cattle who is much worried over the Ghost Dances. All Indians between the forks of the Cheyenne and Cherry Creek, except Red Bull of Big Foot’s village and Yellow Owl, who lives at Cherry Creek, four miles from the mouth—Low Dog is the leader of the dance at Cherry Creek. Hump (late Chief of Police) has moved with ten families on Reservation lately he dances to see what there is in it… No trouble… unless an attempt is made to stop….

Indians present at the issue were armed with Winchester Guns, cal 44… plenty of ammunition and well manned… between 400 and 500 warriors were present at the issue in the opinion of Lt. Evans. Indians are friendly at Cherry Creek, and about the Camp, but dislike the Indian Police very much.

On 28 November 1890, Capt. Hennisee reported that Touch the Cloud recommended enlisting him and other head men as scouts. Of note is that by this date, the military campaign was well underway with troops arriving daily at the Pine Ridge and Rosebud reservations.

‘Touch the Cloud’, one of the Head men among the Indians came to me yesterday with the suggestion that the Government enlist him and the other head men as scouts, so as to give them authority over the people that they might stop the Ghost dances, that the Indians were in such a state now that only they could not be prevented by the Head men from dancing unless they had authority from the Government. He also suggested that as many influential men as possible be enlisted, that he thought that the older and most sensible men would be willing to serve as scouts at this particular time and until affairs were in a quiet state, that he feared that if something of that kind was not done, that the older men would not be able to control the young ones. The principal men are to have a Council on the subject on the 30th inst. at ‘Big Foot’s’ village and let me know the result….

I respectfully and earnestly recommend that authority be granted to enlist fifteen of the principal men and oldest sons of families so that it can be done quickly should they conclude to enlist. I am confident that they will.

Capt. Hennisee on 2 December 1890, reported that Big Foot recommended at an Indian council that none of the Indians should enlist as scouts.

I learned last night [of the] result of the Indian Council held in Big Foot’s village on Nov. 30th ‘90. Big Foot advi[sed that] no one enlist as scouts that they continue [dan]cing and if interfered with in their religious meetings to fight. Bear Eagle sent me word that he would not enlist but help the Government all he could, that he could do more good by not enlisting. Hump sent me word that he would enlist if General Miles said so. When here on the 27th Touch the Cloud advocated drum dances among the Indians, that being different from the Ghost dances. The dance with the drum is kept up continually and vigorously at Big Foot’s village for the purpose of keeping the Indians from going away, to occupy them and wear out and disgust them with dancing. I like the plan…. “I am confident that enough of the leading men and oldest sons of families can be enlisted to control the Indians completely, regardless of ‘Big Foot’s’ influence, in fact I think that his opposition would be just what the men who would enlist as scouts would need to confirm their own opinions.

This was the last letter signed by Hennisee, as shortly after this report, Lt. Col. Sumner arrived and assumed command of the Camp on Cheyenne River. Most of Sumner’s correspondence is included in the National Archives 1974 compilation of Reports and correspondence related to the Wounded Knee Investigation and Sioux Campaign of 1890-1891.

Capt. Argalus G. Hennisee’s reports from the camp of observation on the Cheyenne River from April to December 1890, layout a military strategy to remove what the Army and the Indian Bureau saw as the most disturbing elements among the Miniconjou Lakota. By separating Big Foot and his most extreme followers from the majority of the otherwise peaceful band, the government sought to avoid any potential outbreak or conflict.

At first glance, Grabill’s photograph of the Great Grass Dance in August seems to demonstrate community and ceremonial tradition that momentarily prevailed over conflict. Knowing the outcome of Wounded Knee makes the photograph all the more tragic and indicates the failure of the Army’s strategy. None of Big Foot’s followers were enlisted as scouts, he and his most extreme adherents were not separated from the peaceful elements, and the band did break away from the 8th Cavalry and the Cheyenne River, perhaps making the tragedy at Wounded Knee unavoidable.

Endnotes

1 U.S. Indian Census Rolls, 1885-1940, Year: 1890, Roll: M595_33, Page 106, Line:1; Charles E. McChesney, “Report of Cheyenne River Agency” dated 25 Aug 1890, Fifty-Ninth Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1890, 42.

2 Herbert T. Hoover, “The Sioux Agreement of 1889 and Its Aftermath,” South Dakota History, South Dakota State Historical Society, 1989, 58; Robert M. Utley, The Last Days of the Sioux Nation, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1963, 80-82. Of all the historians to write on Wounded Knee, Utley is the only one that details the camp of observation. However, Utley assumes malign action on the part of Big Foot that summer stating that he, “angrily led his band up Cheyenne River [from the reservation]. Eighty miles west of the agency they built cabins.” Hennisee’s reports clearly show that Big Foot’s band did not move from the reservation that summer and had lived in their present location for about eight years.

3 Henry B. F. MacFarland, District of Columbia: Concise Biographies of Its Prominent and Representative Contemporary Citizens, and Valuable Statistical Data, 1908-1909, Washington: The Potomac Press, 1908, 218-219; “The Apaches of New Mexico.” The St Louis Republic, 10 Jul 1872, 4.

4 8th U.S. Cavalry Regimental Records, Letters Sent by a Detachment in the Field in South Dakota, 1890-91, Vol. 1, RG: 391, Entry No: 901, Box No: 1 Vol., Stack: 9W2, Row: 28, Compartment: 19, Shelf 4. National Archives research conducted by Vonnie S. Zullo of The Horse Soldier Research Service.

5 The author originally prepared to present these fourteen letters to the 2024 Order of the Indian Wars Assembly at Rapid City, SD, but due to time constraints reduced the presentation to portions of ten letters.

6 Analysis of the Lakota language was made using Google Gemini, for “Lakota translations for Black Coyote, Black Fox, and Black Wolf” query, November 3, 2025. The AI analysis utilized the following sources: Albert White Hat Sr., Reading and Writing the Lakota Language: Lakota Iyapi un Wowapi nahan Yawapi (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1999); Eugène Buechel, S.J., A Dictionary of the Teton Dakota Sioux Language: Lakota-English / English-Lakota, ed. Paul Manhart, S.J., 11th printing (Pine Ridge, SD: Red Cloud Indian School, 2002).

Citation for this article: Samuel L. Russell, “Watching Big Foot: The Camp of Observation on the Cheyenne River,” Army at Wounded Knee (Carlisle, PA: Russell Martial Research, 2018-2025, https://wp.me/p3NoJy-1WV) last updated 3 November 2025, accessed date __________.

Hi Sam— I very much appreciate having this for my Wounded Knee files, and thanks for sending it. I enjoyed your OIW presentation greatly, and hope to see you again along the way. All best wishes to you and yours for the upcoming holidays. Jerry

>

LikeLiked by 1 person