I then called to the captain that it was squaws, and he replied “Don’t kill the squaws.” I said – it is too late, I am afraid they are already killed.

–First Sergeant Herman Gunther

Three weeks after Wounded Knee an Indian policeman named Red-Hawk, who had been searching for his sister since the battle, found her remains and those of her children near White Horse Creek. He returned to the Pine Ridge Agency and reported his discovery of the bodies. Major General Nelson A. Miles, perhaps concerned with Captain Edward S. Godfrey’s testimony two weeks earlier that “My men had killed one boy about 16 or 17 years old, a squaw and two children,” gave Captain Frank D. Baldwin instructions to locate the bodies and determine what happened. On January 21, 1891, Baldwin submitted the following report:

I proceeded this morning at 7 A.M., under escort of a detachment of the 1st Infantry, mounted to White Horse Creek, about eleven miles distant, where I found the bodies of one woman, adult, two girls, eight and seven years old, and a boy of about ten years of age. They were found in the valley of White Horse Creek, in the brush, under a high bluff, where they had evidently been discovered and shot. Each person had been shot once, the character of which was necessarily fatal in each case. The bodies had not been plundered or molested. The shooting was done at so close a range that the person or clothing of each was powder-burned. The location of the bodies was about three miles westward of the scene of the Wounded Knee battle. All of the bodies were properly buried by the troops of my escort. From my knowledge of the facts, I am certain that these people were killed on the day of the Wounded Knee fight, and no doubt by the troop of the 7th Cavalry, under the command of Captain Godfrey.

(Click to enlarge) Goodenough Horse Shoe Mfg. Co. had been supplying the U.S. Army with horseshoes and horseshoe nails since at least 1874.

Tracks of horses shod with the Goodenough shoes were plainly visible and running along the road passing close by where the bodies were found. A full brother of the dead Indian woman was present. He had been on the agency police force for several years. Considering the distressing circumstances attending the death of his sister, his demeanor was remarkably friendly. His only request was that a family of three persons, the only relatives he has living, and who were of Big Foot’s band, may be allowed to remain at this agency. This I recommend be granted. I returned to the agency at 3 P.M. Very respectfully, Your obedient servant, Frank D. Baldwin, Captain, 5th Infantry, A. A. I. G.[1]

Almost a week after Baldwin returned from his ominous burial duty, correspondent George H. Harries of the Washington Evening Star published an article in that paper that heightened eastern outrage over Wounded Knee. Although run on page six, the attention grabbing headlines undoubtedly shocked the readers in the nation’s capital, “A Prairie Tragedy. How a Sioux Squaw and Her Three Little Ones Met Death. Tracing the Murderers. A Sad Scene Near Pine Ridge—The Discovery and Burial of the Victims of a Brutal Assassination—Cowardly Crime by Men Wearing the Blue.”

Pine Ridge, S. D., January 22,.—War, barbaric at the best, is legitimate, but there can be no possible excuse for assassination. Today I witnessed the last scene in the earthly history of four of God’s creatures. They were Indians and they lacked much. Education had done nothing for them and the softening touch of religion had not smoothed their way to eternity, but they had souls, and those who killed them as the assassin kills are murderers of the most villainous description. No one who looked upon that scene can ever forget it, and not a man or woman who is acquainted with the facts but regards the bloody circumstances with anything save horror. An Indian woman, comely in life, with her three children were brutally murdered at about the time of the Wounded Knee fight and within three miles of the battlefield. Yesterday their bodies were discovered by an Indian policeman; today the remains of the unfortunate quartet were placed in the bosom of mother earth. When it became known at division headquarters yesterday that four dead Indians had been found Capt. Baldwin of the fifth infantry and now on staff duty was instructed to proceed to the spot accompanied by a sufficient force for the purpose of identifying and burying the deceased. Sunshine and frost combined to make this morning pleasant enough to make South Dakota a reputation as a winter resort. Ordinarily two or three men would be able to inter four people, but these are still times of war and the revengeful Indian will lose no opportunity to wreak a portion of his vengeance on weaker parties than the one he commands. For that reason company A, first United States infantry, was ordered to perform escort duty and also to furnish a burial party. Lieut. Barry and his men have only recently been mounted on Indian ponies and there is perhaps a little friction because men and cayuses do not yet understand each other, but the command was ready before the hour specified—7 a.m.—and after a slight and unavoidable delay on the part of others who were to go along the column moved out of the settlement and to the eastward. Two ladies—one of them a newspaper correspondent, the other simply morbidly curious—were with the little expedition, the latter daughter of Eve being in a buggy commanded by Dr. Gardner, the former on one of Gen. Miles’ pet horses. Twelve miles from the agency was the spot to which our guides led us, the place where Red Hawk, an Indian policeman, had yesterday found the bodies of his sister and her children. Red Hawk, the scouts, Interpreter Frank White and myself rode ahead of the column and arrived there some minutes in advance, leaving the main trail and our destination over a bridle path that narrowed at times to a dangerously insufficient footing even for a careful horse. Red Hawk went alone to the little patch of brush in which lay those he loved, the remainder of the advance guard considerately halting on the bank above the bloody scene until it might be regarded as proper for them to approach and see for themselves what a cowardly deed had been done. Oh, it was a pitiful sight. Mother and children had never been separated during life and in death they were not divided. Prone and with the right side of her face frozen to the solid earth was the squaw “Walks-carrying-the-red.” Snow almost covered an extended arm and filled the creases in the little clothing she wore. Piled up alongside of her were her little ones, the youngest with nothing to cover its ghastly nakedness but a calf buffalo robe, which is before me as I write. The positions of the children were changed somewhat from those in which they were found, the discoverer putting them together that he might cover them with a blanket. The first body to be examined was that of a girl about nine years of age. In the horrible moment preceding dissolution she had drawn her arms up and placed them across her face—a pretty face, say those who knew her—and as the features molded themselves on the bony arms and froze her visage became frightfully distorted. A black bead necklace was embedded in the flesh of her throat. The victim was killed by being shot through the right lung, the ball entering high in her breast and making its exit at the right of her back, near the waist. Her sister—less than seven years old—was almost naked. She, too, was facing the murderers when they took such deadly aim and, like the other girl, she had tried with her arms to shut out the sight of the unwavering rifle muzzles. The ball entered her right breast, went through the right lung downward and came out near the spine and just above the left kidney. Seventy grains of powder drove 500 grains of lead through the brain of the boy—a sturdily built twelve-year-old. Of all the horrible wounds ever made by bullets none could be more frightfully effective than that which forever extinguished the light of life in this boy. The wound of entrance was on the upper part of the right side of the head; the wound of exit was beneath the right eye, tearing open the cheek and leaving a bloody hole as large as a dollar. There must have been at least a few seconds of agony before death came, for the right arm was thrown up to and across the forehead and the fingers of the left hand stiffened in death while clutching the long, jet-black hair near the powder-burned orifice in his skull. And the mother. Gentle hands loosened the frosty bands which bound her to the soil and fingers which tingled with the hot flow of blood from indignant hearts tenderly removed from her flattened and distorted face the twigs and leaves and dirt which in the death agony had been inlaid in the yielding features. Her strong arms were bare and her feet were drawn up as the natural consequence of a wound which commenced at the right shoulder and ended somewhere in the lower abdominal region. From the wounded shoulder a sanguinary flood had poured until her worn and dirty garments were crimson-dyed; the breasts from which her little ones had drawn their earliest sustenance were discolored with the gory stream. It was an awful sight; promotive of sickening thought and heartrending memories. While Dr. Gardner, Capt. Baldwin and Lieut. Barry were satisfying themselves as to the direct causes of death a detachment from the escort had prepared a shallow grave. It was on the brow of the hill immediately above the scene of crime. Red Hawk had selected the spot and it did not take long for half a dozen muscular infantrymen to shovel away the light soil until the bottom of the trench was about three feet below the surface. In one blanket and covered by another the bodies of the three children were borne up the slope and laid alongside their last resting place. When the detachment returned for the mother Red Hawk took from under his blue overcoat a few yards of heavy white muslin, which he shook out and placed over his sister’s body. Then everybody went up the hill. The mother was first placed in the grave, and upon and alongside of her were the children. Not a sound of audible prayer broke the brief silence. The warm sun shone down on the upturned faces of Elk Creek’s widow and children and searching January breeze played among their ragged garments. “Fill her up, men,” said Lieut. Barry, and that broke the spell. In five minutes a little mound was all that denoted the place from whence the four bodies shall rise to appear before the judgment seat, there to face four of the most despicable assassins this world ever knew.

Who were these murderers? There is where the shame comes in. They were and still are soldiers in the army of the United States; “things” who wear the honorable blue and who claim the protection of a flag under which women and children enjoy more rights and are accorded greater privileges than man gives to the weaker and the younger in any other part of the world. The chain of evidence is complete, even to the identity of the individuals who committed the deed. Indian eyes found most of the testimony; military precision supplied the rest. The first link was the finding of an empty Springfield cartridge shell near the dead bodies. Had the killing been done by Indians and had the Indians thrown out the useless shells they would have been of the Winchester variety. Upon the trail near the little patch of brush were the tracks of sharp-shod horses. No Indian’s horse wears shoes. The tracks were made on the day following the battle, for they were in the direction of Wounded Knee, and snow had covered them up in places. On the day of the battle no troops moved in that direction; on the day after some did; then came the snow. In the bank on which the villains laid down to pour a plunging volley into the bodies of the refugees, who were about two or three feet below them, are the marks of boot toes. Out in the road and partially covered by snow was a little doll. String the testimony together and you will find that on the 30th day of December, 1890, this woman and her three children were on their way to the agency. They had escaped the slaughter which on the previous day had included the husband and father, in whom they were most interested. When near this place in which their bodies were found they saw the coming soldiers, and it was most natural that they should seek the shelter of this half acre or so of thick brush. But the soldiers saw them and neither sex nor helplessness could save the footsore wanderers. Unarmed and without protection of any description they were wontonly and knowingly slain. Not one of the men who fired those shots can say that he was unaware of the character of his victim, for each wound shows that the rifle muzzles were within a few inches of the individuals at whom they were aimed. Hair and clothing is not burned by the explosion of a cartridge, which is in a gun a hundred yards away from the object that is hit. Burnt powder only flies a short distance and its flame travels but a couple of feet at most.

Gen. Miles knows what soldiers passed that way that morning. They were few in number and he can easily ascertain who the wretches were. What is he going to do about it?

G. H. H.[2]

General Miles mentioned the incident at White Horse Creek specifically in his January 31, 1891, endorsement to the investigation of the battle of Wounded Knee in which he unequivocally found fault with Colonel James W. Forsyth’s handling of the affair. “I also forward herewith report of Captain Frank D. Baldwin, 5th Infty., concerning the finding of the bodies of a party of women and children about three miles from the scene of the engagement on Wounded Knee Creek. This report indicates the nature of some of the results of that unfortunate affair, results which are viewed with the strongest disapproval of the undersigned.”[3] On February 12, 1891, Secretary Redfield Proctor directed an investigation into the circumstances surrounding the killing of the Indian woman and her children:

The bodies of an Indian woman and three children who had been shot down three miles from Wounded Knee were found some days after the battle and buried by Captain Baldwin of the 5th Infantry on the 21st day of January; but it does not appear that this killing had any connection with the fight at Wounded Knee, nor that Colonel Forsyth is in any way responsible for it. Necessary orders will be given to insure a thorough investigation of the transaction and the prompt punishment of the criminals.[4]

That same day Captain Godfrey had four of his troopers, who were involved in the shooting of the mother and her children, provide depositions to a local Geary County notary public. On March 2, General Miles returned the notarized statements and a memorandum summarizing the event with a full paged endorsement wherein he seemed to blame Godfrey while at the same time relieved him from any responsibility. Apparently Miles was only interested in holding Forsyth accountable for actions at Wounded Knee.

The woman and children killed were in the camp of Big Foot on Wounded Knee Creek. In his testimony at the investigation of the Wounded Knee Creek affair Captain Godfrey states that his men killed one boy, one squaw and two children. His testimony as to the locality where these people were killed coincides with the report of Captain Baldwin as to the spot where the bodies were found. Captain Baldwin’s report, which accompanied the papers pertaining to the Wounded Knee Creek investigation, shows also that the tracks of a troop of cavalry horses were found near the bodies, as well as other evidences of the presence of soldiers. The boy, however, was not sixteen or seventeen years of age, but between eight and ten, and the two girls between five and seven. Captain Godfrey subsequently admitted that this party was killed by his men, but gave as an excuse for them that he did not think they could see the Indians on account of the brush. Persons who were on the ground and examined the brush could easily be identified in that locality at a distance of fifty yards. The weight of this excuse, however, is entirely destroyed by the fact that the soldiers could see well enough to take deliberate and deadly aim and kill four persons with six shots, and so near were they as to burn the clothing and flesh of every victim, and one of their United States cartridge shells was found in the midst of the dead bodies. In my opinion, however, Captain Godfrey was not responsible for this crime. All the facts were not ascertained until the regiment was ordered out of this Division, and this incident was regarded in the same light as that of others which occurred in other parts of the field.[5]

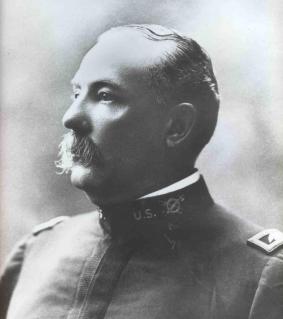

Photograph of Colonel Peter D. Vroom, circa 1899, courtesy Wikipedia

Major General Schofield, through the Adjutant General of the Army, next directed Brigadier General Wesley Merritt, Commanding General of the Department of the Missouri to whom the 7th Cavalry was assigned, to conduct a further investigation. The task eventually fell to Major Peter Dumont Vroom, General Merritt’s Inspector General. Vroom was forty-eight years old and had served as a company grade officer for twenty-two years in the 3rd Cavalry before being promoted to the the rank of major in the Inspector General’s Department in 1888.[6]

Major Vroom received his orders on March 13 and conducted interviews with Captain Godfrey, and four enlisted soldiers from D Troop on the 17th and 18th. Vroom began with an interview of the Troop commander and asked Captain Godfrey, “Please state the circumstances with the killing of a party of Indians by a detachment under your command on the 29th of December 1890, after the fight on Wounded Knee Creek.” Godfrey replied with the following:

We were scouting down a creek, which I understand now to be White Horse Creek, and were in a gorge. I was looking to the flanks and also to see if there were any tracks on the ground of anybody that had passed there. Sergeant Gunther and some of the men called out: “Look out, there, Captain, there are some Indians down the creek there.” I halted the detachment, I had about twenty men with me and asked how many Indians they had seen. They replied that they had seen three crouching and running across the creek. My detachment was in column of twos. I dismounted half of the men and told Sergeant Gunther to take some men and deploy them across the creek valley. The other dismounted men I sent to the left on the high ground. While they were taking their posts, I called out several times: “Squaw,” “Pappoose,” “Colah,” and tried to indicate in the best way I could that if they were squaws or children they had no reason to fear us. Sergeant Gunther then called my attention and said: “Captain, they will get the advantage of us if we stand here.” I was waiting for the men on the left to get into position and also waiting to get responses from the Indians. When the men first began to go out I cautioned them particularly against shooting squaws and children, and when they were ready to advance I gave this caution again. I then told the non-commissioned officers to move their squads forward very carefully. Sergeant Gunther’s men moved forward crouching down pretty close to the ground, and pretty soon some one called out: “There they are,” and they commenced firing. I heard the wail of a child and called to them to stop firing, but they had already stopped. The party was then about twenty-five or thirty yards from where the Indians were found. I immediately ran forward to where the bodies were and saw at a glance a boy, squaw and two children lying there. The look was sufficient to satisfy me that I could do nothing for the squaw and children. The boy was lying on his face motionless and I supposed he was dead. I had already ordered the men to continue on down the creek and was turning away hurriedly to look after my detachment when I heard a shot and Blacksmith Carey said: “Captain, the man ain’t dead yet,” and I saw that he had shot him. The horses remained back where the men were dismounted. After examining the creek and ravine below, I called for the led horses. The road led down the valley of the creek, which was narrow, crooked and full of brush. The road passed right near where the bodies were, within a few feet of them.[7]

Major Vroom next asked Captain Godfrey, “Did you notice that the flesh or clothing of any one of the bodies was burned?” Godfrey replied, “I did not, nor do I believe that my men were close enough for the bodies to be powder-burned by their fire, except in the case of the boy. I took the boy to be about fifteen or sixteen years of age.” Major Vroom followed up with, “How thick was the brush at the place where the Indians were found?”[8] Godfrey responded with:

It was such that I did not see them at any time until I went up to the bodies. I am satisfied that the men did not know at what they were firing except that they were Indian, because Sergeant Gunther, as soon as he heard the wail of the child, dropped the butt of his gun on the ground, leaned his weight on it and shook his head in a sorrowful manner. Blacksmith Carey was a recruit who had joined us three weeks before, and when he shot a thought went through my mind that he had evidently heard of the ruses and desperation of wounded Indians. It is a well-known fact that old soldiers take no chances with wounded Indians. In conversation with Captain Baldwin, subsequent to his report of the burial of the bodies, he said that the boy had but one gun shot. Of course then the boy had not been hit in the first firing.[9]

Major Vroom concluded his interview with Captain Godfrey with one final question. “Did your detachment move or handle the bodies at all?” Godfrey answered:

They did not. I have understood from parties who were present, and also from a letter of a newspaper correspondent who was present with Captain Baldwin at the time of the burial that the position of the bodies had been changed after a snow had fallen on them, and it is my belief that if the bodies were powder-burned it was done by some parties subsequent to the day of the fight with malicious intent and purpose to deceive. The fight took place on the 29th of December, 1890.[10]

Major Vroom next began interviewing the enlisted men involved in the shooting. Vroom’s time in the 3rd Cavalry would bode well for one of the soldiers who was also a veteran of the 3rd. Herman Gunther, a native of Baden, Germany, was an experienced forty-five-year-old cavalryman and the senior non-commissioned officer of Captain Godfrey’s D troop. He initially entered the army in 1868 as a young twenty-two-year-old jeweler from New York City. He served for fifteen years in C troop, 3rd Cavalry Regiment, and was discharged from that unit in November 1883 at Fort Thomas, Arizona Territory, having risen to the rank of first sergeant. After six months working as a butcher in St. Louis, Gunther signed up for his fourth five-year enlistment and was assigned to the 7th Cavalry’s D troop. Rising again to first sergeant of his unit by the time D troop arrived at Wounded Knee, First Sergeant Gunther along with Captain Godfrey, ensured that D troop was ably led by two veteran cavalrymen, both with more than two decades in the saddle.[11]

Major Vroom next began interviewing the enlisted men involved in the shooting. Vroom’s time in the 3rd Cavalry would bode well for one of the soldiers who was also a veteran of the 3rd. Herman Gunther, a native of Baden, Germany, was an experienced forty-five-year-old cavalryman and the senior non-commissioned officer of Captain Godfrey’s D troop. He initially entered the army in 1868 as a young twenty-two-year-old jeweler from New York City. He served for fifteen years in C troop, 3rd Cavalry Regiment, and was discharged from that unit in November 1883 at Fort Thomas, Arizona Territory, having risen to the rank of first sergeant. After six months working as a butcher in St. Louis, Gunther signed up for his fourth five-year enlistment and was assigned to the 7th Cavalry’s D troop. Rising again to first sergeant of his unit by the time D troop arrived at Wounded Knee, First Sergeant Gunther along with Captain Godfrey, ensured that D troop was ably led by two veteran cavalrymen, both with more than two decades in the saddle.[11]

Major Vroom recorded the following statement from First Sergeant Gunther regarding the shooting at White Horse Creek.

Captain Godfrey with one platoon was following a party of Indians that got away from the battle-field and went up a deep ravine leading toward the hills. We were trying to cut them off. The Indians were seen several times by us, but always in such a way that we could not get at them. I should judge that there were about fifteen Indians in that party. When we got to the head of the ravine, we halted. Captain Godfrey and myself then examined the country around closely with field glasses, but were unable to see any signs of the Indians. After staying there quite a while Captain Godfrey started back with the platoon. Just as we were coming around a bend in the road leading down into the bottom, I saw some Indians dodging into the brush. My impression at the time was that we were on to the party of Indians that we had been following up. I called Captain Godfrey’s attention to it, saying to look out as we were right on top of them. The Captain ordered myself and several men to dismount and move forward. At the same time the Captain sung out “How Colah.” In moving ahead Private Kern, who was off his horse quicker than I was, got ahead of me a few paces. I noticed Private Kern raise his carbine and on looking in that direction I saw Indians that were hiding in the bottom of a dry creek. I was unable to distinguish what they were, the brush being so thick Private Kern fired the first shot. I fired immediately after him. As soon as I fired there was some screaming done by a child. The captain then sung out again “How Colah,” and said “Don’t kill any squaws.” I replied that I was afraid it was too late. I am positive that the object I aimed at did not move after I fired. The one that done the squealing was behind the object and must have been wounded by my ball. I then sent Private Kern to the right of me on some high ground with instructions to watch the brush from up there. Myself and Private Settle, who had come up in the meantime, went through the brush down the creek, but we did not find any more Indians. I had not been closer than from twenty to twenty-five yards to the Indians we shot at.[12]

Major Vroom than asked the first sergeant if he could distinctly see the Indians when he fired.

I could just see the outline of something lying close to the ground. The brush was very thick. It was thicker between me and the Indians than it was between Kern and the Indians. I had to fire right through the brush. After I fired I went down the creek and did not see the bodies of the Indians. The captain told me that there was one woman and three children in there killed. There were only three shots fired, one by myself and two by Private Kern. After I got a little way down the creek I heard another shot fired in our rear, but I did not know at the time who fired it.[13]

In the course of Major Vroom’s investigation into the killing of a Lakota woman and her three children, he next interviewed Blacksmith Maurice Carey, a twenty-three-year-old emigrant from Northern Ireland who had enlisted in the army at Wheeling, West Virginia, in the middle of September 1890. He was one of the new recruits that joined the regiment at Pine Ridge at the beginning of December. Carey was a horseshoer by trade prior to entering the military and Captain Godfrey appointed him to the vacant blacksmith position in D troop in the middle of December. Carey had light blue eyes, light brown hair, a fair complexion and stood five feet eight and a half inches tall. He provided Major Vroom with the following statement.[14]

We were going through a ravine and saw a party of Indians trying to cross. Then we were dismounted and I ran back about twenty yards and fired a shot and then I went up over the bluff and came down to the captain. Then we were looking at those Indians and I caught one by the hair and lifted him up. He looked at me and pulled himself away and made a movement and I jumped away from him and shot him through the head. I shot him because I was afraid he was going to shoot me.[15]

When asked how old the Indian was, Carey responded, “I took him to be seventeen or eighteen years old. He was pretty tall. I took him to be as tall as me.” Major Vroom next asked the blacksmith how close he was to the Indian when he shot. “I could not say.” replied Carey. “I jumped away from him as quickly as I could and then shot him.” “Was he lying on the ground when you shot him?” queried the investigator. “Yes, sir.” was the answer. The inspector general concluded the interview by asking, “How long have you been in the service?” to which Carey replied, “A little over six months.”[16]

Major Vroom next interviewed Private William Kern, a twenty-three-year-old German emigrant who had been working as a baker when he enlisted at Newark, New Jersey, two years earlier. Kern was short in stature standing just five feet four inches with hazel eyes and brown hair. Private Kern provided the following statement:

After the shooting at Wounded Knee was over, we were ordered by Captain Godfrey to mount our horses and follow up a ravine. We followed that ravine along and came upon open ground, where we saw an Indian about two miles ahead of us. After we had looked over the ground carefully, we could not see any signs of other Indians and turned off to our right going down towards a big ravine full of underbrush and a road leading through the ravine from one end to the other. As soon as we came down the ravine the road bent to the left. As soon as we came around that bend we seen Indians. Captain Godfrey was riding in front and me and 1st Sergeant Gunther right behind him. Then we caught a glimpse of one Indian who appeared to be a buck. As soon as he saw us he jumped from the road and Captain Godfrey halted the command and told Sergeant Gunther to dismount and take some men and be prepared. There was me and Private Settle and Sergeant Gunther dismounted. The rest of the troop was sent out to the right and left of the ravine. As soon as we were dismounted, Captain Godfrey hallooed out twice: “How Colah,” and while he hallooed out “How Colah,” I was ahead and 1st Sergeant Gunther following me on the right side of the ravine in a kind of a washout, and we could see the head of an Indian twenty-five yards away. Captain Godfrey didn’t get any answer. By that time I had loaded up and Sergeant Gunther the same. I fired first and Sergeant Gunther Immediately after me. As soon as I had fired I reloaded again. I heard an Indian grunting, but it was too late for me to stop and I pulled off my second shot. Sergeant Gunther ordered me then to go along the ravine and search careful and he says he expects a lot of Indians in that ravine. Private Settle came on the left of me to help search the ravine. We went through that ravine carefully and couldn’t find nothing else. There was a log house in front of us on top, and we went up and searched that.[17]

Inspector General Vroom asked Private Kern if he could distinctly see what he was aiming at when he fired at the Indians, to which Kern responded, “I could see a head that I was aiming at. The Indians were lying down in the same washout that we were in. The underbrush was very thick. I did not see the Indians after they had been killed.” Major Vroom concluded the interview by asking Kern how far he was from the Indians when he fired. “About twenty-five yards, just the width of the ravine.” was Kern’s reply.[18]

The final witness that Major Vroom questioned was Private Green Adam Settle, a thirty-one-year-old native Kentuckian. He had served for three years with the Fifth Cavalry at Camp Supply, Indian Territory, in the mid 1880s and enlisted into the 7th Cavalry in January 1889. According to his most recent enlistment record, Private Settle stood just under five feet nine inches, had gray eyes, light hair and a fair complexion. Settle provided the following account to the inspector.

Coming down the ravine Captain Godfrey was leading the detachment, Sergeant Gunther was next to Captain Godfrey, Private Kern and myself were first in column. There were some Indians, I could not say how many, that appeared right in front of us in the road, and some one from behind had seen the Indian first and cried out: “There is Indians ahead of us.” The captain didn’t seem to see them at first and I didn’t see them till some one spoke. As soon as I saw them I only saw one, and he ran across the road into the under brush. The captain ordered the 1st Sergeant to dismount some men and go ahead. Sergeant Gunther, Private Kern and myself was the three men to dismount. Kern was in front, Sergeant Gunther was next to him and I was last. Private Kern moved on to where he saw the Indian run out of the road and fired two shots into a little ravine where the Indians had hid. Sergeant Gunther fired one shot and we then moved on down the ravine. There was a road running down the ravine and I was on the left side of the road as we went and Kern was on the right. We went on out as far as the brush was thick until it began to get open, to an old house. After we had looked around there, the detachment came up and we mounted our horses and went away.[19]

Major Vroom asked Settle if he could see the Indians when Private Kern and First Sergeant Gunther fired.

No, sir. There was a kind of dry creek or ravine that they were in that must have been twenty-five yards from the road. The underbrush and grass were very thick. I was about twenty-five yards from Sergeant Gunther and Private Kern when they fired. I did not see what they fired at. I did not see the Indians after they came out of the road. After the shots were fired, Captain Godfrey advanced toward where the Indians were and called out “How Colah.” Then he told Gunther to send men on down and search out the ravine. I went on down the ravine and did not see any more Indians. I did not see the bodies of the Indians that had been killed.[20]

Having questioned all of the soldiers involved in the incident, Major Vroom concluded his investigation with a summation of testimony he had collected. Writing on March 24, 1891, from the Inspector General’s Office, Department of the Missouri in St. Louis, Vroom forwarded the following report through department headquarters to the adjutant general’s office at the War Department.

It appears from the evidence adduced that on the 29th of December, 1890, immediately after the fight at Wounded Knee Creek, Captain E. S. Godfrey, 7th Cavalry, with a detachment of his troop, was in pursuit of a party of about fifteen Indians, who had escaped from the battle-field, and were making their way through a deep ravine toward the hills. On his return, while moving down along the valley of what he subsequently learned to be White Horse Creek, it was reported to Captain Godfrey that Indians had been seen in his front in the creek bottom. Captain Godfrey halted his detachment, dismounted half of it and ordered a non-commissioned officer to take some men and deploy them across the valley of the creek, while the other dismounted men were sent to the left on the high ground. While his men were deploying, Captain Godfrey called out several times to the Indians: “Squaw,” “Pappoose,” “Colah,” and tried in every way to indicate to them that if they were squaws or children they had nothing to fear. The men of the troop had previously been particularly cautioned against shooting squaws and children and when they were ready to advance on this occasion the caution was repeated. First Sergeant Herman Gunther was in charge of the squad directed to move down the ravine. After waiting for sometime to give the men on the left time to get into position, and also to receive responses from the Indian, Captain Godfrey ordered his non-commissioned officers to move their squads forward very carefully. The men under Sergeant Gunther advanced close to the ground and soon commenced firing. Captain Godfrey, hearing the wail of a child, called to them to stop firing, but they had already stopped. The party was then about twenty-five or thirty yards from where the Indians were found to be. Captain Godfrey immediately went forward to where the bodies were and found a boy, a squaw and two children lying there, the squaw and children dead, and the boy, who was lying on his face, apparently so. At this juncture, Blacksmith Maurice Carey, who after the first firing had gone around on top of a high bluff, from which he could see the dead Indians in the creek bottom, joined Captain Godfrey. As the latter turned away to look after his detachment, Blacksmith Carey took hold of the Indian boy’s head to lift him up. As he did so, the boy opened his eyes and made a movement that evidently frightened Carey, who jumped back and shot him through the head. Blacksmith Carey states that he shot the Indian because he was afraid the Indian would shoot him.

But five shots were fired during this affair, one by Sergeant Gunther, two by Blacksmith Carey and two by Private Kern. The evidence shows that the brush in the creek bottom was very thick and that the men could not distinctly see what they were firing at. The Indians were evidently lying down and close together when shot. With the exception of the last shot fired by Blacksmith Carey, which killed the Indian boy, all of the shots were fired at distances of from twenty to thirty yards, precluding the possibility of the person or clothing of every Indian having been powder-burned.

The whole affair lasted but a few moments. The men were excited and there seems to be no doubt that they believed that the Indians seen belonged to the party they had pursued from the battle-field. The killing of the woman and children was unfortunate, but there is nothing to show that it was deliberate or intentional. First Sergeant Gunther is an old soldier of the 3d Cavalry and has been personally known to me for many years. That he would deliberately shoot down women and children I do not believe. Blacksmith Carey is a recruit and at the time of this occurrence had been but three weeks with his troop. As suggested by Captain Godfrey, it is probable that his action in killing the Indian boy was prompted by what he had heard from old soldiers of the ruses and desperation of wounded Indians. Opinions differ as to the age of the Indian boy. Captain Godfrey thinks that his age was 16 or 17 years, while Blacksmith Carey states that he was 18 or 19 years old and as tall as himself.[21]

Major General John M. Schofield, Commanding General of the Army, endorsed Major Vroom’s report on April 2 adding, “In my judgment no further action is required in this case.” The report was marked “Seen by the Secretary of War” and filed with the Adjutant General’s Office.[22]

The following November Captain Baldwin wrote to the infantry officer who had accompanied him the previous January when the bodies were discovered and buried. Captain Thomas H. Barry, who in January was a First Lieutenant in K Company, 1st Infantry, responded to Captain Baldwin on November 24, 1891.

On Tuesday January the 20th, 1891, in command of a detachment of thirty (30) mounted men of the First Infantry, I left Pine Ridge Agency S.D., at 7.30 O’Clock A.M., and proceeded to White Horse creek, where I arrived at 10.00 O’Clock A.M., and there found the bodies of four dead Indians – a squaw and her three children, one a boy about ten years old, and two little girls, one about eight and the other about six years of age. The squaw was shot under the right shoulder blade, there being no exit wound, the little boy was shot on the left side of the head, the ball coming out under the right eye, the hair where the bullet entered being singed; the little girl who had fallen in front of her mother, was shot in the right breast, the ball coming out at lower left side of the back, and the little girl—the youngest child—who fell just to the right of her mother, and who at the time, must have been hanging to her skirts, was shot in the back, the ball coming out at the right breast. All the shots ranged downwards. About two feet to the left and a little in rear of the squaw an empty cartridge shell marked F-88-9 was found. The position of the bodies indicated that they had been shot at the same time and from above, the result of a volley delivered near enough to them to have power-burned each. The print of the hoof of an American horse shod with “Goodenough” shoe was found in the road about thirty yards down the creek. Red Hawk, brother of the squaw, an Agency policeman, accompanied us and at his request the bodies were buried on the hill above and a little in front of where they were found. The above is taken from notes made by me at the time and copied into my diary upon my return to camp at Pine Ridge Agency. The squaw and her children were evidently making their way from the “Wounded Knee” battle field to the Pine Ridge Agency by an out-of-the-way and not usually travelled [sic] route, when they were discovered and killed. They were skulking through the brush along the White Horse creek, having left the road to avoid detection by their pursuers, whom they undoubtedly saw or heard. No weapon or anything resembling one, was found on or near the bodies.[23]

Hand written on the back of the letter, possibly by Captain Baldwin or General Miles, was the following notation, “Angel Island, Cal., Nov. 24, 1891. Capt. Thomas H. Barry. Statement as to condition of woman and children powder burned when shot near Wounded Knee Creek, S.D.” The letter was not forwarded to the War Department and the investigation remained closed.[24]

More than a decade following the Pine Ridge campaign, E. S. Godfrey, by then a Colonel, was actively seeking promotion to flag officer rank. He wrote to the Adjutant General of the Army in July 1902, “to request that I be appointed a Brigadier General.” President Roosevelt held a negative view of Wounded Knee, and after reviewing General Miles’s investigation, he had determined that Godfrey was personally responsible for the killing of non-combatants at Wounded Knee and would never be promoted again in a Roosevelt administration.[25]

A common practice in the Army at that time was that prominent citizens would conduct a writing campaign to the War Department and the President on behalf of a colonel they endorsed for promotion. In 1903 U.S. Senator Levi Ankeny from the state of Washington, where Colonel Godfrey was stationed at Fort Walla Walla, wrote to the President seeking a generalship for Godfrey. President Roosevelt apparently responded suggesting that the Senator reconsider based on Godfrey’s role in the killing of women and children at Wounded Knee. The senator decided to look into the matter himself, contacting officers who knew the circumstances surrounding Wounded Knee and requesting Colonel Godfrey provide him his version of events. Colonel Godfrey responded to the senator with a letter saying, “While I am deeply grateful that you should, unsolicited, feel enough personal interest in me to request my advancement, words cannot express my appreciation of the kindness which gives me an opportunity to defend myself when I had no idea that a defense was necessary.” Included with the colonel’s letter was a five-page manuscript that Godfrey typed and signed on December 31, 1903. His account was similar to earlier testimony and differed only in that Godfrey recalled that his soldiers discharged their weapons only after he gave the command “commence firing” and promptly ceased firing on Godfrey’s command. He stressed that dead leaves on the brush obscured his and the soldiers’ view such that they knew they were firing at Indians, but could not tell they were women or children.[26] Godfrey also related details after Captain Baldwin and Lieutenant Barry found and buried the bodies. Following is the latter portion of Godfrey’s 1903 manuscript.

Sometime after the investigation had closed Lieut. T. H. Barry… came to my tent and told me he had commanded the escort to take Capt. Baldwin out to where my men had killed the squaw and children; that there were tracks of persons in the snow around and near where the bodies were found, that all the bodies were powder marked. I think he said the bodies had been moved from their original positiond [sic], but the places where they had been could be plainly distinguished in the snow. My recollection is that he said on their way back to Pine Ridge Baldwin asked him what he, Barry, thought about it and that Barry was non-committal. Then Baldwin said, to this effect, “It looks pretty bad but I don’t know that I blame him,” meaning me. Barry said he told me this as it might be important for me to do something about it. I said that I had testified to about all that was to be said before the Court of Inquiry and said it was impossible that the squaw and girls could be powder marked when killed….

It afterwards appeared that some newspaper correspondents were taken along (in fact it was a newspaper expedition) so that the horrors and brutalities etc., could be properly verified and exploited to the world. One of the correspondents was George H. Harris [sic: Harries], of the Washington Eve-Star.

I don’t believe (but of course cannot be positive) that Barry knew the objects of the expedition–but I think he had a suspicion and hence his warning to me. I relied on the integrity of the affair and supposed integrity of the investigation. I was not aware of the attendance of newspaper correspondents.

I was severly injured in a [rail road] wreck on our return to Fort Riley and never saw the correspondence, nor did I ever see anything of Baldwin’s report. Nothing was said to me by any one at Pine Ridge up to the day of our departure by Miles, Baldwin or correspondents.

The 7th Cavlary left Pine Ridge about January 21. After we had been on the march for several miles, an orderly was sent to me saying General Miles wanted to see me. I reported at Pine Ridge and he (Miles) said the bodies of a squaw and children had been found and it was believed they had bend [sic] killed by my men. I related the circumstances and told him I had testified the whole matter to the Court of Inquiry. He then went on to say how he thought they had been killed, etc., that my men had crawled up over an embankment behind them and shooting down had killed them as they were hiding under this bank; that my men were so close that the bodies were all powder burned. I told him my men had not crawled up behind them and that it was impossible for the woman and girls to be powder burned. I said that I could not see them at all and that my men were between 35 and 50 yards away and could not distinguish what they were on account of the bushes with dead leaves, but could only get a glimpse of their positions. He said there were not enough bushes there to interfere and that my men were close enough to powder burn them. I replied that I was there and knew what I was talking about and if the woman and girls were power burned it was done by somebody else and not by my men–That I and my men regretted it as much as any body could, but it was a misfortune and not wanton. That when I heard the wail of those children, I could only think of my own little children at my home.

The investigation then stopped. He asked after my personal affairs and the interview closed.

I had not a thought when I quitted his presence but that I had fully established the innocence of myself and my men from anything wanton or brutal. General Miles in his report of the campaigns or the review of the action of my regiment charged to the effect that my men had been guilty of wanton creulty in the killing of the woman and children but that I was not responsible. It exonerated me from blame, but held my men responsible….

I was not satisfied to be exonerated myself and have my men held to blame and was consulting some of my friends as to the best procedure as soon as I should be able to attend to the matter. While I was still in the Hospital at Fort Riley, Kans., Major P. D. Vroom… came to Fort Riley and investigated the whole matter, taking the testimony of myself and all the men engaged in the valley who did any shooting and perhaps others. I never saw his report, but I was given to understand that he exonerated both my men and myself. It must have been so, for nothing further was said or done about it that I ever heard of….

While I was on sick leave I was ordered to Washington…. Not long afterward I got a letter from Capt. Barry… saying he had received a letter from Capt. Baldwin… asking him to give him his recollections of what they had seen when they went out to visit the scene of the killing of the woman and children by my troop. Barry said he didn’t know Baldwin’s purpose in making this request but thought he should let me know of it.

I went to Col. J. S. Gilmore, A. A. G., then in the War Department related the circumstances from beginning to end and asked him to let me know if there was anything in the Department that was derogatory to me or my men in that affair that was not satisfactorily explained. He said he would investigate and let me know. After several days he told me there seemed to be nothing, and that everthing [sic] was all right; that if anything came up or came in he would let me know. He assured me on several occasions that nothing had come up.[27]

Senator Ankeny forwarded Colonel Godfrey’s manuscript along with another letter to President Roosevelt again recommending Godfrey be promoted. No such promotion was forthcoming. There is another letter of interest in Edward Godfrey’s file in the National Archive’s regarding President Roosevelt’s refusal to promote the cavalry colonel. From his retirement home in Columbus, Ohio, Major General James W. Forsyth wrote on June 22, 1904, to the Secretary of War, William H. Taft.

I have heard, through friends in Washington, that information had been given to the President, of such a character as to cause him to conclude that Colonel E. S. Godfrey, of the Regular Army, had been “harsh, cruel, and even brutal,” at the fight at Wounded Knee, with the Sioux Indians, by the 7th cavalry, which regiment I commanded at the time, and that on Colonel Godfrey’s efficiency record an entry had been made charging him with the wanton killing of women and children at Wounded Knee.

My regiment and I had the misfortune to incur the enmity and disapproval of General Miles on that occasion, and a long and tedious investigation occurred at the time, covering all the allegations made by General Miles, including the accusation of the unnecessary killing of women and children, which I presume is referred to in the present reflections upon the character and record of Colonel Godfrey.

It was an entirely one-sided investigation, in which absolutely no defense was made by either myself or the 7th cavalry, and notwithstanding this fact we were completely exonerated, not only by the then commanding general of the army, General Schofield, but by the then Secretary of War, Mr. Proctor. So far as my knowledge goes, even the report of General Miles did not hold Colonel Godfrey personally responsible for the unfortunate and unintentional killing of some women and children by members of his troop during the engagement as above mentioned.

At any rate, this occurrence was subsequently investigated by Colonel Peter Vroom, Inspector General, who exonerated Colonel Godferey from any personal culpapbility or responsibility for the said killing of women and children.

I have known Colonel Godfrey for a long time, and I assure you that harshness, cruelty, and brutality are entirely foreign to and inconsistent with his real character. I always esteemed him as one of the best officers in my regiment, and one of the best and worthiest in the service.

All of the investigations mentioned above are fully covered by records which must now be on file in the War Department, and I sincerely trust that you will find time to look over these records carefully, and that erroneous impressions or unjustifiable entries on his record will not be permitted to do grave injustice to a worthy soldier.

I take much pleasure in cordially recommending Colonel Godfrey for advancement in the service. I have no personal interest whatever in this matter, and this letter is a voluntary effort to vindicate a former worthy subordinate, and has not been solicited either directly or indirectly by Colonel Godfrey, who knows nothing about my writing this letter.[28]

Roosevelt eventually did promote Godfrey to brigadier general in 1907 likely based on the counsel of Major General J. Franklin Bell, Chief of Staff of the Army and fellow former 7th Cavalry officer who had served with Godfrey during the Pine Ridge campaign. However, the promotion came in Godfrey’s sixty-fourth year when he would be retired by law, and, thus, not be eligible for promotion to major general. In 1931 at the request of the Chief of Staff of the Historical Section of the U.S. Army War College, General Godfrey wrote a letter recounting his reminiscences of Wounded Knee and White Horse Creek. With only slight variations, his recollection was in line with his 1891 testimony and his 1903 manuscript.[29]

Regarding the lives of the other individuals involved in the White Horse Creek tragedy, Blacksmith Maurice Carey, the Irishman from Wheeling, West Virginia, was discharged from the army at Fort Riley for disability in January 1892 with a characterization of service of ‘excellent.’ His life after the army is lost to history.[30]

Private William Kern, the German emigrant from Newark, New Jersey, was shot in the face during the Drexel Mission fight along the White Clay Creek the day after the Wounded Knee battle. Kern drowned on September 20, 1891, while fishing in the Kansas River, still assigned to D troop at Fort Riley. The army ruled his death was not in the line of duty. He was buried in the Fort Riley Post Cemetery.[31]

Settle A. Green is buried in the A. R. Dyche Memorial Park in London, Kentucky.

Private Green A. Settle of Jackson County, Kentucky, continued his service with the 7th Cavalry. During the Spanish American War, he served as the first sergeant of troop H, in the 1st U. S. Volunteer Cavalry, the Rough Riders, which was one of the elements of the regiment that did not go to Cuba. After the war and seventeen years in the cavalry, he settled in London, Kentucky, where he worked as a barber. About 1903 he married twenty-one-year old Annie Reams and they had six children together. Green Settle died in 1946 and his wife 1969.[33]

First Sergeant Herman Gunther and his wife, Emma, are buried in the San Antonio National Cemetery.[35]

First Sergeant Herman Gunther enlisted two more times ultimately retiring on June 19, 1899, at Fort Riley, Kansas, after thirty years of service. At the time of his retirement he was still serving as D troop’s first sergeant. He married eighteen-year-old Emma Kramer, a dress maker from Junction City, Kansas, in 1892. The Gunther’s settled in San Antonio, Texas. They had one son, Arthur, born in 1895. Herman Gunther died in 1931, Emma in 1945.[34]

The names of the children of Walks-Carrying-the-Red, her son and two daughters who were shot and killed along White Horse Creek at the hands of the cavalrymen of D troop, remain unrecorded, their bodies resting in unmarked graves where they were buried with their mother by Captain Baldwin and Lieutenant Barry’s party on January 21, 1891, three weeks after their deaths.[36]

Red-Hawk was photographed numerous times by several renowned western photographers. This photo was taken by Edward S. Curtis, circa 1913.

Austin Red-Hawk, the Oglala policeman who discovered the bodies of his sister, nephew, and nieces and brought the burial party to their location on White Horse Creek, later served as a corporal in Detachment D, U.S. Indian Scouts. Born in 1854, he was 22 when he helped defend his village against the 7th Cavalry along the Greasy Grass, a river the soldiers called the Little Big Horn. He lived the remainder of his life at Pine Ridge with his wife, Alice, their three children, Susie, James, and Noah, and his other sister, Cedar-Woman. In his last years, he received a pension from the government for his service as a scout. Red-Hawk died in 1928.[37]

Endnotes

[1] Kent and Baldwin Investigation, 732-733.

[2] George H. Harries, “A Prairie Tragedy: How a Sioux Squaw and Her Three Little Ones Met Death,” Evening Star (Washington, D. C.: 27 Jan 1891), 6.

[3] Kent and Baldwin Investigation, 767.

[4] Peter D. Vroom, “Investigation of circumstances connected with shooting of an Indian woman and three children by U.S. Troops near the scene of the battle of Wounded Knee Creek,” in Reports and Correspondence Related to the Army Investigations of the Battle at Wounded Knee and to the Sioux Campaign of 1890–1891, the National Archives Microfilm Publications (Washington: The National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration, 1975), Roll 1, Target 3, Jan. 1891, 1136.

[5] Ibid., 1139-1140.

[6] Adjutant General’s Office, Official Army Register for 1912, (Washington: War Department, 1912), 478.

[7] Ibid., 1145-1147.

[8] Ibid., 1147-1148.

[9] Ibid., 1148.

[10] Ibid., 1148-1149.

[11] Register of Enlistments in the U.S. Army, 1798-1914, (National Archives Microfilm Publication M233, 81 rolls), Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1780’s-1917, Record Group 94, National Archives, Washington, D.C.,

[12] Vroom Investigation, 1149-1151.

[13] Ibid., 1151.

[14] Register of Enlistments in the U.S. Army, Years: 1885-1890, Range: A-D, Page: 255, Line: 304.

[15] Vroom Investigation, 1151.

[16] Ibid., 1152.

[17] Ibid., 1152.

[18] Ibid., 1153.

[19] Ibid., 1153-1154.

[20] Ibid., 1154-1155.

[21] Ibid., 1142-1145.

[22] Ibid., 1441.

[23] Thomas H. Barry, letter to Frank D. Baldwin dated 24 Nov 1891, Nelson A. Miles Papers (Carlisle, PA: Military History Institute), box 4, Sioux War, 1890-1891 Wounded Knee, Pullman Strike, Commanding General.

[24] Ibid.

[25] NARA M1395, Letters Received by the Appointment Commission and Personal (ACP) Branch, within the Adjutant General’s Office, 1871-1894 (Record Group 94), Roll: M1395_Gillmore-Granger, File Number: 6626 ACP 1876, Name: Godfrey, Edward S., 288-604.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid. Edward S. Godfrey’s manuscript that he mailed to Senator Ankeny was later published in The 1963 All Posse-Corral Book of the Denver Posse of the Westerners with an introduction and biographical details by Barry C. Johnson, page 66-72. Following article was a republished lecture by George H. Harries describing his work as a correspondent during the campaign, including much of the text from his article quoted in this post. Barry C. Johnson republished his article with Godfrey’s manuscript in the April-July 1977 Brand Book vol. 19, page 1-13.

[28] Ibid., 629-630.

[29] Associated Press, “Brig. Gen. Godfrey Retired,” The Sun (New York: 10 Oct 1907), 2; Peter Cozzens, ed., Eyewitnesses to the Indian Wars, 1865-1890, (Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books, 2004), 615-619.

[30] Register of Enlistments in the U.S. Army, Years: 1885-1890, Range: A-D, Page: 255, Line: 304.

[31] Ibid., Page: 331, Line: 34; National Archives and Records Administration, Burial Registers of Military Posts and National Cemeteries, compiled ca. 1862-ca. 1960, Archive Number: 44778151, Series: A1 627, Record Group Title: Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774-1985, Record Group Number: 92.

[32] Stephen and Andrea Brangan, “Green Adam Settle,” FindAGrave, (http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=78186393) accessed 23 May 2014. Uploaded 1 June 2012.

[33] Register of Enlistments in the U.S. Army, Years: 1893-1897, Range: L-Z, Page: 92, Line: 56; Ancestry.com, U.S., Spanish American War Volunteers, 1898 [database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012, Original data: General Index to Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Soldiers who Served During the War with Spain, Microfilm publication M871, 126 rolls, ARC ID: 654543, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1780s–1917, Record Group 94; Ancestry.com, United States Federal Census [database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2004, Year: 1900, Census Place: London, Laurel, Kentucky, Roll: 537, Page: 1A, Enumeration District: 0147, FHL microfilm: 1240537; Ancestry.com, Kentucky, Death Records, 1852-1953 [database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007.

[34] Ancestry.com, United States Federal Census [database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2004, Year: 1900, Census Place: San Antonio Ward 6, Bexar, Texas, Roll: 1611, Page: 12A, Enumeration District: 0100, FHL microfilm: 1241611; Year: 1910, Census Place: San Antonio Ward 6, Bexar, Texas, Roll: T624_1531, Page: 8A, Enumeration District: 0048, FHL microfilm: 1375544; Year: 1930, Census Place: San Antonio, Bexar, Texas, Roll: 2296, Page: 25B, Enumeration District: 0105, Image: 556.0, FHL microfilm: 2342030; Year: 1940, Census Place: San Antonio, Bexar, Texas, Roll: T627_4205, Page: 10B, Enumeration District: 259-143; “Kansas, Marriages, 1840-1935,” index, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/FW2B-2JM : accessed 30 May 2014), Herman Gunther and Emma Kramer, 14 Jul 1892, citing Junction City, Geary, Kansas, reference p 159; FHL microfilm 1685972; Ancestry.com, Texas, Death Certificates, 1903–1982 [database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2013, Original data: Texas Department of State Health Services. Texas Death Certificates, 1903–1982. iArchives, Orem, Utah, Ancestry.com, U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962 [database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012, Original data: Interment Control Forms, 1928–1962, Interment Control Forms, A1 2110-B. Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985, Record Group 92, The National Archives at College Park, College Park, Maryland.

[35] Laura T., “Herman Gunther,” FindAGrave, (http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=96751442) accessed 23 May 2014. Uploaded 24 Apr 2013.

[36] The Westerners Brand Book, vol 19, 1963, page 82 provides detail as to the identity of the Lakota woman, “Mother and children were not divided even in death, Prone, and with the right side of her face frozen to the solid earth was the squaw ‘Walks-Carrying-The-Red.’ Snow almost covered an extended arm and filled the creases in the little clothing she wore. Piled up alongside of her were her little ones, the youngest with nothing to cover its ghastly nakedness but a calf buffalo robe.”

[37] Ancestry.com, U.S., Indian Census Rolls, 1885-1940 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007), Year: 1904; Roll: M595_369; Page: 62; Line: 6, Agency: Pine Ridge; Ancestry.com, United States Federal Census (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2004), Year: 1900, Census Place: Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, Shannon, South Dakota, Roll: 1556, Enumeration District: 0046, FHL microfilm: 1241556; Year: 1910, Census Place: Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, Wounded Knee, South Dakota, Roll: T624_1475, Page: 26A, Enumeration District: 0119, FHL microfilm: 1375488; Year: 1920, Census Place: Township 40, Washington, South Dakota, Roll: T625_1725, Page: 5A, Enumeration District: 214, Image: 1125; National Archives and Records Administration, U.S., Civil War Pension Index: General Index to Pension Files, 1861-1934 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2000), Name: Redhawk, State Filed: South Dakota, Widow: Alice Red-Hawk, Roll number: T288_387; Ancestry.com, South Dakota, Death Index, 1879-1955 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2004), Certificate Number: 116041, Page Number: 782; Edward S. Curtis, photo., from http://www.American-Tribes.com (http://amertribes.proboards.com/thread/803), posted 3 Dec 2009, accessed 14 Jan 2017.

Note: An earlier version of this essay was posted on 23 May 2014. It has been updated to include information originally posted in “Testimony of Captain Edward Settle Godfrey, Commander, D Troop, 7th Cavalry,” the letter from Captain Thomas H. Barry, and files from Godfrey’s personnel file including his 1903 manuscript of the tragedy at White Horse Creek. Block quotes of the troopers earlier depositions dated 12 Feb 1891 were removed as they were redundant to the testimony provided to Major Vroom and already presented.

Citation for this article: Samuel L. Russell, “Investigation of the White Horse Creek Tragedy,” Army at Wounded Knee (Sumter, SC: Russell Martial Research, 2013-2014, http://wp.me/p3NoJy-ju), posted 18 January 2017, accessed _______.

Hi Sam,

I notice that the place of birth for Myles Moylan is incorrect – it should be Tuam, Co. Galway.

LikeLike

Mairéad… Thank you for the comment. I do address the conflicting information regarding Myles Moylan’s year and place of birth in the following post: https://armyatwoundedknee.com/2013/09/15/captain-myles-moylan-a-troop-7th-cavalry/

LikeLike