Send me more men; there is a whole raft of them; let’s get them out; I don’t know what they are.

In December 1890, thirty-nine-year-old John Gresham was an experienced officer that had been with the 7th Cavalry for over fourteen years. He had been the First Lieutenant of B Troop for more than a decade, and commanded the unit a number of times. He played an active role during the campaign and the events leading up to the surrender and disarming of Chief Big Foot and his band of Lakota, as well as the battles along the Wounded Knee and White Clay creeks. For unexplained reasons, Lieutenant Gresham was not called to testify during Major General Miles’ investigation of the Wounded Knee affair. The mention of him in the testimony and reports of other officers, and his Harper’s Weekly article, “The Story of Wounded Knee,” detail some of his actions during the campaign. In his article, Gresham provided a description of the composition and experience of his unit as they headed out on December 26 to the Wounded Knee Post Office with orders to find and capture Big Foot’s band of Miniconjou and the remnants of Sitting Bull’s Hunkpapa that had joined them.

Each battalion has four troops. The First, to which I belong, is commanded by Major S. M. Whitside, and at Wounded Knee had 232 men and ten officers. Of the men, eighty one were new, but little trained as soldiers, and not at all as marksmen. Thirty-eight had joined at Pine Ridge only a few days before they were called on to fight. Prior to this campaign eighty-five percent of our men had seen nothing of Indians—indeed, had no knowledge of them beyond what is usually acquired at home by city or country boys of their class and station.[2]

Continuing with his article, Gresham articulated the 7th Cavalry’s understanding of Chief Big Foot’s band in late December 1890, a view informed by reports from Indian agents, military reports, and dubious newspaper articles.

Big Foot’s band was the worst of their race, and had they been disarmed, would have been sent as prisoners of war to Gordon, Nebraska, and thence by rail to a distant point. They belonged at the Cheyenne Agency, and were trying to penetrate our lines and join the hostiles in the Bad Lands of White River. On leaving home they had cut up their harness, broken their wagons, and shown clearly their intention of going to war.[3]

Later historians have persuasively argued that the destination of the Miniconjou was the Pine Ridge Agency, and not the hostile camp in the Stronghold, and that Big Foot’s intent was to serve as a peaceful mediator with the differing Lakota factions. As the cavalry aggressively searched up and down Wounded Knee Creek, they understood the missing band to be anything but peaceful. Major S. M. Whitside in his official report detailed Gresham’s role in the search for Big Foot’s band on December 27.

Lieut. J. C. Gresham, 7th Cav’y, with twenty-one (21) men, was sent up Wounded Knee Creek to the State line, with Instructions to thoroughly scout that country and ascertain if any Indians had crossed the creek to my south during the night.

Lieut. Gresham returned about 4 P.M. and reported he had seen no signs of Indians.[4]

Regarding the Lakota band’s surrender the following day to Major Whitside, Gresham continued in his article:

Deducting an officer and twenty-five men left to guard camp, and including Lieutenant H. L. Hawthorne and the detachment of artillery, our force amounted to 225 men and ten officers. Leaving one-fourth of the line troopers to hold horses, our line of battle had 170 men and ten officers.

Suddenly appeared indications of dispersion in the right wing of the hostile line, and several bucks broke off and galloped to our left. It looked like the beginning of trouble. But when sternly called to and motioned back, they returned, and all signs of scattering disappeared. Experienced officers pronounced the Indians “a saucy set,” and quietly warned the soldiers to be ready. After a short conference Big-Foot surrendered his band, declared his heart was good, and that he loved the pale-faces. There were 120 warriors, well armed and supplied with ammunition. They were escorted to our camp, near which ground was assigned for their village.[5]

Upon the successful capture of the Miniconjou Lakota and return to the 7th Cavalry camp at the Wounded Knee post office Gresham in his article mentioned his role in guarding the Indian camp the night of December 28 and 29:

Officers said and felt they would rather shoulder a gun and do duty as sentinels than see the Minneconjoux have the slightest chance left them of a second escape. I was officer of the guard, and never saw duty as well done. The night was cold, invited rapid motion of sentinels on their beats, and made sleep impossible even for the reserve.[6]

Gresham went on to describe the attempts to disarm the band, the outbreak of hostilities, and the melee that ensued:

It was now evident the bucks were armed….

Personal search must now be made at all hazards. It proved more deadly than an attempt to deprive of their claws an equal number of tigers, for the search was hardly begun when the whole body of painted, bedizened fanatics sprang as one man, or rather as one demon, flung off their blankets, and with nothing but breech clouts and light ghost shirts to impede their marvelous agility, began emptying their magazine rifles into the ranks of the soldiers. The fire was returned instantly and with great effect, so that after a desperate struggle of a few minutes the surviving bucks made a headlong rush for the village, and thence into the adjacent ravine. Here they met death from the men of A and I troops, dismounted and disposed on that side. The frightful hand to hand conflict which followed the attempt at personal search fell to the lot of B and K troops. Never were men called upon to meet a more sudden, more pressing, and more perilous crisis, and never was crisis more manfully met.[7]

Following the shift of the battle from the council circle and Indian village to the dry ravine, Colonel Forsyth directed B Troop to “take 20 men and clear the ravine.”[8] Captain Varnum detailed Gresham’s role in this portion of the battle when he testified to the action Gresham took in accomplishing this task.

In that ravine there was lot of dead and wounded Indians. One of my men crawled up who spoke Sioux, and an Indian said “I am an Oglala.” Lieut. Gresham said, “see if he has a gun, and if there is no danger leave him,” and we left him. Shortly after Lieut. Gresham, who was near me, yelled, “Send me more men; there is a whole raft of them; let’s get them out; I don’t know what they are.” I concentrated the detail and Pvt. Spinner commenced to talk Sioux to them, when some 19 women and children came out, and I took them out of the ravine and sent Spinner with them to camp.[9]

Gresham mentioned in his article this same incident and the discretion his troops took in avoiding the unnecessary killing of women and children. “I found nineteen concealed in the ravine, and sent them under guard to a place of safety. They seemed greatly surprised and very grateful, and in their savage ignorance expected nothing but death.”[10]

Gresham was listed among the wounded by Colonel Forsyth and General Miles in all official correspondence and reports. Captain Varnum made no mention in his muster roll for December 1890 of Gresham’s being wounded likely because he did not require hospitalization and continued his duties. Ernest Garlington in his History of the Seventh Regiment of Cavalry wrote that Gresham “received an abrasion on the nose from a passing bullet.”[11] Frederic Remington writing for Harper’s Weekly at the end of January quoted a wounded officer that likely was Lieutenant Gresham.

To appreciate brevity you must go to a soldier. He shrugs his shoulders, and points to the bridge of his nose, which has had a piece cut out by a bullet, and says, “Rather close, but don’t amount to much.” An inch more, and some youngster would have had his promotion.[12]

Captain Varnum was duly impressed with the performance of his first lieutenant. Just two weeks after returning to Fort Riley following the campaign, Varnum prepared a letter to recognize Lieutenant Gresham. The captain does not specify what he was recommending Gresham receive–honorable mention, a Medal of Honor, or a brevet promotion–perhaps leaving that to the discretion of the regimental commander.

Fort Riley, Kansas, February 14th, 1891.

I have the honor respectfully to invite the attention of the Regimental Commander to the conduct of 1st Lieut. J. C. Gresham, of my Troop, (B) 7th Cavalry, while in action with hostile Sioux Indians, Dec. 29th, 1890.

The Colonel Commanding will recall that I was ordered with twenty men of my Troop to go up the ravine on the south of the Indian village, from the pockets of which concealed Indians were firing on and hitting and wounding our men, and clear it of the enemy. Lieut. Gresham accompanied me. The ravine was deep, with cut banks, very crooked, and afforded excellent cover for concealed enemies. It was strewn with dead and wounded Indians, many of whom were able to use their arms, though unable to get away. It was necessary to hold and control both banks of the ravine and also send a party up the bottom to scout and examine the net work of corners and angles and bring out the women and children, if such were found. This duty was extremely difficult and dangerous–especially as it was impossible to distinguish the dead, wounded and nests of women and children, the one from the other, and what might appear to be women might prove to be a formidable and desperate enemy. Lieut. Gresham asked to be allowed to lead the party up this bottom. He worked carefully, patiently and coolly, up the ravine, searching among the dead and wounded, brought out Nineteen women and children, disarmed some wounded men, was always in the lead himself, and continued to advance until orders were received from the Regimental Commander to withdraw. He was cool and deliberate as though there was nothing to fear, although in addition to the dangers already mentioned was the constant danger of suddenly running into those who were still unhurt and who had been firing on the Troops at every opportunity.

I think Lieut. Gresham worthy of recognition for his gallant conduct on this occasion.

Again on December 30th, 1890, when the Troop formed part of a dismounted skirmish line in action in the Valley of White Clay Creek, S. D. The position was for a while an important one, covering the withdrawal of other troops, and holding the crest of a ridge.

Orders for our withdrawal had been given and the movement commenced, when a heavy fire opened on our line while falling back, which threatened for the moment to demoralize it. Orders were given to at once retake and hold the crest. Lieut. Gresham ran among the men, catching hold of three, and by word and example urged them back. The line was re-occupied, but not until our fire had silenced that of the Indians did Lieut. Gresham leave his erect position on the crest of the ridge. This was done under a heavy fire and the act was, I think, well worthy of the notice of the Regimental Commander.

I am Sir, Very Respectfully, Your Obedient Servant.

Chas. A. Varnum,

Captain 7th Cavalry, Commanding Troop B.[13]

Major Whitside endorsed the letter and three weeks later Colonel Forsyth recommended five officers receive honorable mention in orders: First Lieutenants Robinson, Gresham, and Brewer, and Second Lieutenants Tompkins, Preston, and Nicholson. Forsyth did not include Varnum’s letter in his recommendation, and the Adjutant General’s Office returned the recommendations requesting additional details as to Gresham’s actions. The letter that Forsyth wrote did not contain enough detail as to what Gresham had done to deserve recognition. Colonel E. M. Heyl’s investigation into acts of gallantry included statements from several officers regarding the actions of Lieutenant Gresham.[14]

Captain Nowlan, Troop I commander, stated, “Lieut. Gresham rendered me a great deal of assistance while on the line. He was exposed to a very severe fire during the whole time, and acted in a very gallant manner.” Captain Varnum added to his earlier letter, “I saw Lt. Gresham, 7th Cav’y. go into the ravine (at Wounded Knee) among the wounded Indians, with a pistol in his hand, disarming the dead and wounded Indians. I consider his conduct under the circumstances conspicuous and gallant, as he was liable to be shot at any moment by one of the wounded Indians. Lieut. Gresham also displayed coolness and gallantry at the Mission fight, Dec. 30, 1890.” Lieutenant Sedgwick Rice added, “At Drexel Mission… Capt. Varnum and Lieut. Gresham both sprang forward, leading and cheering their men under a heavy fire from the Indians, retaking the position and driving the Indians back. I thought at the time their conduct was particularly gallant and that they were conspicuous in their bravery.” Captain Edgerly, who commanded the regiment’s second battalion, provided a simple statement that he “noticed several officers under fire who behaved with coolness and bravery, but their acts were not specially conspicuous.” He want on to list Gresham as one of these officers. Finally, Gresham’s battalion commander at Wounded Knee, Major Whitside, testified, “I observed Lieut. Gresham, 7th Cav’y. He was under a heavy fire giving orders to his men and acting in the coolest manner: I regard his conduct as superb.”[15]

In December of that year, General John M. Schofield, Commanding General of the Army, recognized Lieutenant Gresham in General Order No. 100 for actions at both Wounded Knee and White Clay, one of the few individuals to receive accolades for both engagements.[16]

December 29 and 30, 1890. 1st Lieutenant John C. Gresham, 7th Cavalry: For coolness and gallantry while in charge of a detachment of Troop B, in actions against hostile Sioux Indians in the ravine at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota, on the 29th, and on the crest near the Catholic Mission, on White Clay Creek, South Dakota, on the 30th.[17]

Born September 25, 1851, in Lancaster County, Virginia, John Chowning Gresham was the second of four children of Samuel and Kitty Gresham. Samuel Gresham, born in 1810 and the eldest son of John and Margaret (Chowning) Gresham, was an attorney that had served in the Virginia State Legislature in the 1850s. When Samuel married Katharine “Kitty” Dunaway in 1848, he was a widower and she a widow. He brought at least two daughters and three sons from his first marriage and she a daughter. Together they added four more children to this brood: Walter Raleigh, born in 1850; John Chowning, the subject of this post; Mrs. Florence Rebecca Chowning, born in 1852 and died in 1940; and George Sanford, born in 1854 and died in 1880. Samuel Gresham was a wealthy slave owner, with as many as sixteen men, women and children listed as his property in 1860. His eldest son from his first marriage, Samuel Preston, attended the Virginia Military Institute and served in the Confederacy as a Captain of Company F, 47th Virginia Infantry Regiment; he was wounded in the shoulder, contracted Typhoid Fever, and was eventually dropped from the unit’s rolls. Samuel Gresham, the elder, died in May 1873 a year after his son, John Chowning, entered the United States Military Academy at West Point. Kitty Gresham lived to see her son become an officer in the 7th U.S. Cavalry and be commended for gallantry at Canyon Creek; she died in 1887.[18]

Inspired by a familial tradition of service to the Nation, John C. Gresham entered West Point in 1872 and graduated four years later. Gresham was aware not only of his older brothers’ service in the Confederacy, but also of his maternal grandfather, Rawleigh Dunaway’s service during the War of 1812 as a Quartermaster Sergeant in the 92nd Virginia Militia Regiment, and of his great grandfather, William Chowning’s service in the American Revolution serving as a Surgeon’s Mate aboard the USS Tartar. Gresham stood thirty-fourth of forty-eight 1876 Military Academy graduates and was one of four from his class to serve in the 7th Cavalry at Wounded Knee, the others being Lieutenants Garlington, McCormick, and Sickel.[19]

Lieutenant Gresham was originally appointed to the 3rd Cavalry but was reassigned to the 7th a few weeks after graduation following that regiment’s devastating losses at the Little Big Horn. He served during the remainder of that campaign season, and received honorable mention in 1877 from a commander rarely given to commending his officers. Captain Frederick Benteen listed Gresham among three officers of his battalion for their gallantry in the fight at Canyon Creek against Nez Perce Indians.

The gallant charge into and beyond Canon Creek made by this battalion against the Nez Perce Indians led by Chief Joseph and the charge through the gap held by the same Indians in the afternoon of the same day will ever be memorable in the history of Indian fighting and was of such quality as to draw praise and commendation from the detachment of the First United States Cavalry, who witnessed the charge. First Lieut. George D. Wallace, Seventh Cavalry, commanding Troop G, Lieut. John C. Gresham and Lieut. W. J. Nicholson, Seventh Cavalry, are especially recommended for gallantry, dash, and devotion to duty exhibited by them.[20

While stationed at Fort Yates, Dakota Territory, Lieutenant Gresham married Miss Isabel Cass Gilbert on December 22, 1882. She was the twenty-year-old daughter of the post commander, Colonel Charles Champion Gilbert, 14th Infantry, and West Point class of 1846. The Gilbert’s also boasted of a military tradition dating from the American Revolution. Isabel was a member of the Daughters of the American Revolution and had two ancestors who served as officers during the War of Independence: Captain Jonathan Cass and Colonel Henry Champion. John and Isabel Gresham had three daughters and a son: Katherine, born in 1883 and died in 1969; Mrs. Isabel Holliday, born in 1885 and died in 1944; Mrs. Louise VanHorn Harrell, born in 1887 and died in 1972; and son Champion Gilbert born in 1894 at Fort Riley and died a year later at New Orleans.[21]

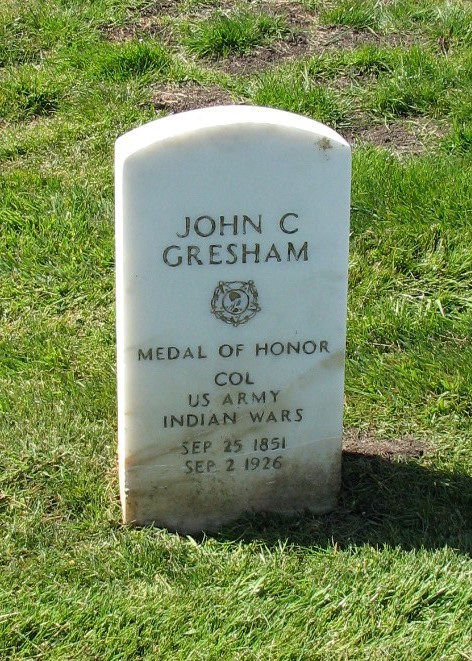

Four and a half years after the battle of Wounded Knee, President Grover Cleveland awarded Captain Gresham the Medal of Honor on March 26, 1895. The citation reads:

Four and a half years after the battle of Wounded Knee, President Grover Cleveland awarded Captain Gresham the Medal of Honor on March 26, 1895. The citation reads:

…for extraordinary heroism on 29 December 1890, while serving with 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. First Lieutenant Gresham voluntarily led a party into a ravine to dislodge Sioux Indians concealed therein. He was wounded during this action.

Of his later career Roger G. Alexander, Secretary of the U.S. Military Academy’s Association of Graduates, wrote the following.

Of his later career Roger G. Alexander, Secretary of the U.S. Military Academy’s Association of Graduates, wrote the following.

Colonel Gresham was a graduate of the Army War College. From September 28, 1876 to December 14, 1896, most of Colonel Gresham’s service was in the West, largely on frontier duty. This service included duty at Fort Lincoln, Standing Rock Agency, Fort Rice and Bear Butte, Dakota, Fort Vancouver, Washington, and Fort Yates, Dakota, where he was on duty guarding construction parties of the Northern Pacific Railroad part of the time. Other subsequent duties included frontier duty at Fort Meade, Dakota, service at Fort Riley, Kansas, Fort Grant, Arizona, mustering officer at Raleigh, North Carolina, in May, 1898 and on duty with his regiment at Havana, Cuba, from March 18, 1899, to September 17, 1901.

He sailed for the Philippines January 1, 1902, and was with the 6th Cavalry in Luzon until June, 1902. He took part in the Malvar campaign, and was on detached service in Lipa and Maguiling Mountains, in command of some six hundred men, and received congratulation and commendation from General J. F. Bell. He was in command of three troops of Cavalry and a company of scouts at Binan in May and June, 1902, during the terrible cholera epidemic, but lost only two men. He was also acting inspector general from June to September, 1903. After serving a tour of duty in the United States, he sailed again for the Philippines in October, 1905 and was Inspector General, Department of the Visayas.

Colonel Gresham was placed on the retired list for age, September 25, 1915. He was a member of the Society of the Cincinnati and the Society of the War of 1812; authorized to wear badges for Indian Wars, Philippine campaign and service in Cuban occupation. He has been also highly commended in the pages of the Army and Navy Journal, the Baltimore Sun and the English Army and Navy Gazette for sundry articles on military subjects. He was recommended for promotion to the grade of Brigadier-General by five different general officers. Colonel Gresham’s people fought on both sides in the Civil War.[22]

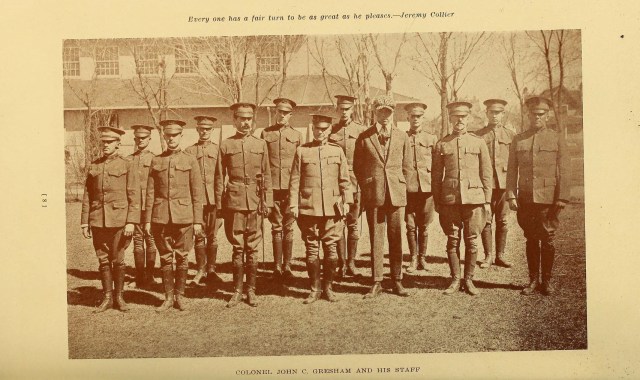

(Click to enlarge) Colonel John C. Gresham and his staff at the University of Denver, 1918. He is the gentleman in the front center with a book in his left hand.[23]

Colonel Gresham was not finished with serving his nation upon his retirement. The following day he was assigned to duty with the California National Guard and served with them until 1918 when he was selected to run the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps and later the Students’ Army Training Corps at the University of Denver, ultimately retiring on December 20, 1918, at the age of sixty-seven. He spent his final years in San Diego where he died September 2, 1926. His wife, Isabel, joined him in death twelve years later. They are buried in the San Francisco National Cemetery.[24]

Colonel John C. Gresham is buried in the San Francisco National Cemetery.[25]

Endnotes

[1] L. T. Butterfield, photo., cropped from “Officers of the 7th Cav at P.R. Age S.D.” Chadron, Nebraska, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University.

[2] John C. Gresham, “The Story of Wounded Knee,” Harper’s Weekly, Vol. XXXV, No. 1781, 106.

[3] Ibid.

[4] National Archives Microfilm Publications, “Sioux Campaign, 1890-91,” Roll 1 Target 3, Jan 1891, 822.

[5] Gresham, “The Story of Wounded Knee,” 106.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] National Archives, “Sioux Campaign, 1890-91,”668-669.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Gresham, “The Story of Wounded Knee,” 106.

[11] Ernest A. Garlington, “Seventh Regiment of Cavalry,” The Army of the United States Historical Sketches of Staff and Line with Portraits of Generals-in-Chief, (New York: Maynard, Merrill, & Co., 1896), 265.

[12] Frederic Remington, Pony Tracks, (New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1895), 50-51.

[13] Adjutant General’s Office, Medal of Honor file for John C. Gresham, Principal Record Division, file 3466, Record Group: 94, Stack area: 8W3, Row: 7, Compartment 30, Shelf: 2. Research conducted by Vonnie S. Zullo of The Horse Soldier Research Service.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] James W. Forsyth, James W. Forsyth Papers, 1865-1932, Series I. Correspondence, Box 1, Folder 1 – Box 2, Folder 49, The Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Libraray, Yale University Library; Medal of Honor file for John C. Gresham.

[17] Adjutant General’s Office, General Orders, G.O. 100 page 4.

[18] Augusta Gresham Bagwell, “Gresham Family,” (1915), 17-20; James M. Baylor, ed., “Family Register Births,” Virginia Genealogical Society Quarterly, Vol. 3, No. 4, October 1965, page 70; Ancestry.com, 1850 United States Federal Census [database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009, Year: 1850, Census Place: , Lancaster, Virginia, Roll: M432_955, Page: 278B, Image: 86, Family Number: 57; Year: 1860, Census Place: Eastern District, Lancaster, Virginia, Roll: M653_1357, Page: 613, Image: 195, Family History Library Film: 805357; Ancestry.com, 1860 U.S. Federal Census – Slave Schedules [database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2010; VMI Archives, Historical Rosters Database, http://www9.vmi.edu/archiverosters/show.asp?page=details&ID=471&rform=search accessed 17 Jan 2014; Ancestry.com, Virginia, Deaths and Burials Index, 1853-1917 [database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011, FHL Film Number: 2048575.

[19] The National Archives, Index to Compiled Service Records of Volunteer Soldiers Who Served During the War of 1812, Roll: M602_0062, State: Virginia, Given Name: Rawleigh, Surname: Dunaway, Regiment: 92 (Chowning, Jr’s,) Virginia Mil, http://www.fold3.com/image/307801042/ accessed 18 Jan 2014; Sons of the American Revolution, “First Lieutenant John Chowning Gresham,” https://www.sar.org/book/export/html/1712 accessed 18 Jan 2014; George W. Cullum, comp., Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the United States Military Academy, Volumes 3 – 6 (Boston and New York: Hougton, Mifflin and Company).

[20] House of Representatives, “Promotion of Certain Officers,” Hearings before a Subcommittee and the Committee on Military Affairs, Sixty-seventh Congress, Second Session on H.R. 10349, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1922), 13.

[21] National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Washington, D.C.; Returns from U.S. Military Posts, 1800-1916, Microfilm Serial: M617, Microfilm Roll: 1476, Post Commander: Charles C Gilbert, Military Place: Fort Yates, Dakota Territory, Return Period: Dec 1882; Martha L. Moody, historian general, Lineage Book: National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution, Vol. 1, (Washington D.C.: Press of Judd & Detweiler, Inc., 1919), 160-161; Orleans Death Indices 1894-1907; Volume: 110; Page: 148; .

[22] USMA AOG, “Fifty-ninth Annual Report of the Association of Graduates of the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, June 8, 1928,” (Saginaw: Seeman & Peters Printers & Binders, 1929), 75-76. John C. Gresham was a member of the Sons of the American Revolution, not the Society of Cincinnati.

[23] University of Denver, University Bulletin, Vol. 19, No. 4, Year Book, 54th Year: 1918, (Denver: University of Denver, 1918), 8.

[24] George W. Cullum, comp., Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the United States Military Academy, Volumes 3 – 6 (Boston and New York: Hougton, Mifflin and Company); Ancestry.com, U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962[database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012, Name: John Chowning Gresham, Death Date: 2 Sep 1926, Cemetery: San Francisco National Cemetery.

[25] David Habben, photo., “San Francisco National Cememtery (Presidio),” United States Cemetery Project, accessed 15 Jan 2014 http://www.uscemeteryproj.com/california/kern/zfolder/from%20David%20Habben/California%202/San%20Francisco%20National%20Cemetery%20(Presidio)/.

Citation for this article: Samuel L. Russell, “First Lieutenant John Chowning Gresham, B Troop, 7th Cavalry – Extraordinary Heroism,” Army at Wounded Knee (Sumter, SC: Russell Martial Research, 2013-2014, http://wp.me/p3NoJy-mt), updated 14 Nov 2014, accessed __________.

![First Lieutenant John C. Gresham at Pine Ridge Agency, c. 1891.[a]](https://armyatwoundedknee.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/lieut_j_c_gresham.jpg?w=640)

I recently came into possession of a digital copy of the majority of award recommendations stemming from the Pine Ridge campaign to include Captain Charles Varnum’s letter recognizing Lieutenant John C. Gresham’s conduct at Wounded Knee and White Clay creeks. I have updated this post on 14 Nov 2014 to include an excerpt from that letter.

LikeLike