I turned to Major Whitside saying “By God they have broken,” and the Indians faced my troop and the next thing we got a volley, and the shooting was lively.

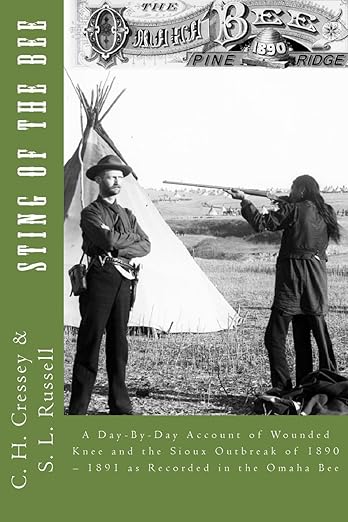

Captain Charles A. Varnum, B Troop, 7th Cavalry, at Pine Ridge Agency, 16 Jan. 1891. Cropped from John C. H. Grabill’s photograph, “The Fighting 7th Officers.”

At forty-one, Captain Charles Varnum, was one of the youngest captains in the regiment at Wounded Knee. He had been promoted the previous July when he was serving as the Post Quartermaster and Adjutant at Fort Sill, Indian Territory. Following his promotion, Varnum took leave and joined his new company, B Troop, at Fort Riley in September just two months before deploying to Pine Ridge at the end of November.

Captain Varnum’s First Lieutenant, John C. Gresham, was present with B Troop at Wounded Knee, but his Second Lieutenant, Edwin C. Bulluck, was not. Bullock deployed with the regiment to Pine Ridge, but quickly became ill and returned to Fort Riley at the beginning of December. Varnum’s First Sergeant was Dora S. Coffey, a young twenty-four-year-old with little more than four years in the Army and the regiment; he did not survive the battle. A review of Varnum’s muster roll for the month of December 1890 indicates that the strength of the troop the morning of 29 December 1890 was up to fifty-seven enlisted men and two officers. Ten recruits from a recruiting depot joined B Troop at Pine Ridge in early December comprising almost 24% of the privates in the company present at Wounded Knee.[1]

Captain Varnum, being a troop commander in Major S. M. Whitside’s battalion at the battle, was the third officer called to testify on the first day of Major General Nelson Miles’s inquiry into the Wounded Knee Affair.

My troop was brought into position from a place it had occupied opposite the head of my company street to one between the Indian circle and their village and facing our camp. I was ordered to take 18 men from my right to search the Indian village, commencing at the north end, the end towards the hill where the battery was located. I commenced the search, and the first rifle I found was under a squaw who was moaning and who was so indisposed to the search that I had her displaced, and under her was a beautiful Winchester rifle. I proceeded up the village, searching everything. I took knives, hatchets, axes, bows and arrows. I got rifles from the pockets of the tepees, and while I was searching Captain Moylan furnished me with a detachment to help carry them off; and nearly all my stuff was carried to the battery. Everything found was so hidden that I had to almost dig for it. One gun was found under the skirts of a squaw, and we had to throw her on her back to get it. After the search in the village, I also took part with a few of my men in the search of the bucks ordered by Major Whitside, telling him that my men said that those bucks are armed with guns under their blankets. He then said we will search them when you are through with the village. Major Whitside and I inspected about twenty Indians on the right of the circle and found no arms or ammunition. We then stood these back, and commenced to pass others between us for the search. Only two or three started which we examined, and I asked Major Whitside if we should take their belts as well as their cartridges, and he told me to let them have their belts. I took a hat and emptied into it the cartridges.

Inset of Lieut. S. A. Cloman’s map of Wounded Knee depicting the scene of the fight with Big Foot’s Band, December 29, 1890.

They all seemed to rise with a purpose of passing through to be searched, when I saw five or six bucks throw off their blankets and bring up their rifles. I turned to Major Whitside saying “By God they have broken,” and the Indians faced my troop and the next thing we got a volley, and the shooting was lively. They knifed some of my men immediately after the break. Shortly after, as soon as I could get at them, I mounted my Troop and reported to General Forsyth, and immediately after was ordered to cover the hospital and some hours after to take 20 men and clear the ravine. I cleaned that up towards the head of the ravine some 150 yards. In that ravine there were lots of dead and wounded Indians. One of my men crawled up who spoke Sioux, and an Indian said “I am an Oglala.” Lieut. Gresham said see if he has a gun, and if there is no danger leave him, and we left him. Shortly after Lieut. Gresham, who was near me, yelled “Send me more men; there is a whole raft of them; let’s get them out; I don’t know what they are.” I concentrated the detail and Pvt. Spinner commenced to talk Sioux to them, when some 19 women and children came out, and I took them out of the ravine and sent Spinner with them to camp. This ends the part I took in the affray.[2]

B Troop, which formed one of the legs around the Indian council, was in the thick of the fight at the opening volley. The unit suffered five killed and eight wounded including two that later died, amounting to a 22% casualty rate in B Troop. The troop’s two officers had close calls themselves. Several years after the battle, Major Ernest A. Garlington wrote a regimental history of the 7th Cavalry in which he related that Lieutenant Gresham suffered an abrasion on his nose from a bullet and that the bowl of Varnum’s pipe was shot off, with the captain still clutching the stem in his teeth at the end of the initial melee.[3]

After the 7th Cavalry returned to Fort Riley and the Secretary of War restored Colonel Forsyth to command of the regiment, he set to work recognizing some of his officers for their conduct. On 14 February 1891, Forsyth recommended:

That Captain Charles A. Varnum, 7th Cavalry, be given a brevet of Major, for conspicuously gallant conduct while engaged under fire, with the Indians of Big Foot’s band at the battle of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, Dec. 29th, 1890. He was commanding his troop (B) one of the troops used in guarding the warriors when the fight began.[4]

The War Department took no action on Forsyth’s brevet recommendations. However, Major General John M. Schofield, Commanding General of the Army, did recognize Captain Varnum, and a number of officers, with Honorable Mention in General Orders at the end of 1891, “For gallant service in action against hostile Sioux Indians, at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota.”[5]

Charles Albert Varnum, born 21 June 1849 at Troy, New York, was the second of seven children and the eldest son of John and Nancy (Greene) Varnum. John Varnum was working as a carpenter in 1850s and ’60s. In 1862, the thirty-nine-year-old carpenter enlisted as a corporal in Company A, 33rd Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. Seven months later he was commissioned a lieutenant in Company C, 82nd Infantry Regiment, U.S. Colored Troops. He received a brevet of Major for gallantry and was eventually mustered out in 1866 at New Orleans at the rank of captain, U.S. Volunteers. Following his service, John Varnum was in charge of reconstruction work at Tallahassee, Florida. His family joined him and settled there where he operated a lumber yard and grist mill, and eventually served as the State Adjutant General. The Varnums moved west sometime after 1880, and Nancy Varnum passed away in 1897 in Colorado. By 1900, John Varnum had settled with his daughter Mrs. Sarah Collins, in Valverde, Colorado, where at seventy-seven he was working as a gold miner. He died in 1911. John and Nancy Varnum had seven children: Mrs. Mary Elizabeth Butler was born 1847 and died in 1873, Charles Albert–the subject of his post, Lydia Ann was born in 1851 and died just before her fifth birthday, John Prescott was born 1854 and died in 1888, Archibald Oakley was born in 1856 and died in 1865, Mrs. Sarah Vivia Collins was born in 1860 and died after 1930, and the youngest child was Henry Archibald born in 1862 and died in 1938.[6]

Charles A. Varnum entered the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York in September 1868, from Florida.[8]

Lieutenant Charles Varnum’s exploits with the 7th Cavalry Regiment are well documented, particularly his role as Lieutenant Colonel George Custer’s chief of Indian scouts on the Little Bighorn campaign and need not be repeated here. As a retired colonel in his seventies, Varnum shared with The Bismarck Tribune a fascinating episode that was likely just one of the many experiences that a young cavalry officer encountered in the unsettled Dakota territory in 1873.

My first visit to Bismarck was in the fall of 1873. I was sent by General Custer to get the body of Blacksmith Dalton, of L troop, 7th cavalry, who was killed by Dave Mullen, who was afterwards killed by the soldiers. I crossed in a yawl to the old ‘Point’ and went up in an ambulance that was sent down from Camp Hancock. I tried to investigate the cause of death, but concluded that discretion was the better part of valor. I got the body down to the boat. The river was running ice, which knocked us about, and twice the coffin went overboard, but we got it ashore at last, and I was about exhausted with the effort.[9]

In November 1885 Lieutenant Varnum oversaw an incident involving the public corporal punishment of the wife of a sergeant in his company. The incident was of such a nature that Varnum was eventually charged and tried by a General Court Martial for conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman. One newspaper wrote that the charges were “of such a character that they cannot be published in any newspaper, and scarcely in a court-martial order.”[10] Varnum entered a guilty plea to the specification, that is the details of the incident, but not guilty to the charge. The jury of his peers found him guilty of a lesser charge of conduct prejudicial to good order and discipline and sentenced him to receive a reprimand in orders by the receiving authority, Brigadier General Thomas H. Ruger. Ruger was livid that the jury did not find him guilty as charged and provided the following reprimand, aimed as much at the jury as at the guilty officer.

…Lieutenant Varnum, acting as troop commander, was present when soldiers of his troop, under his direction, inflicted punishment upon the wife of a non-commissioned officer, by placing her face downward upon a table and beating her with a barrel stave. The conduct of Lieutenant Varnum must, with reference to the charge upon which he was arraigned, be considered the same as though he had done, personally, all that he directed, or permitted, to be done in his presence by men of his command. Infliction of blows upon the person has long since been discarded by most civilized nations, including our own, as revolting to public taste and too degrading to all concerned for retention as a method of punishment. The commanding general cannot concur in view that an officer of the army may be present at and direct the illegal beating of a woman by soldiers under his command, and still be held guiltless of conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman. In his opinion, the acts of Lieutenant Varnum, as admitted in his defence, were so disgraceful to the service, and injurious to discipline in nature and degree, as to sustain the charge set aside by the court; and he cannot, by his approval, aid in establishing so low a standard for estimating propriety of conduct on the part of officers of the army. Lieutenant Varnum will be relieved from arrest and restored to duty.[11]

At the end of 1886, Charles Varnum married thirty-two-year-old Mary Alice “Mollie” Moore, the daughter of George D. and Lydia Moore. George Moore was a riverboat captain from Pittsburgh and had been associated with a number of steam ships including the Winchester, the Forest City, the Eclipse, the Gladiator, the Prima Dona, the Allegheny Belle No. 4, the Bayard, the Argosy, and the Mollie Moore. The wedding took place on 1 December in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The Moore family were not strangers to the Army or the 7th Cavalry. Two of Mollie’s brothers, Frank and Joseph Hayes Moore, were post traders at Fort Abraham Lincoln in the Dakota Territory. Additionally, Mollie’s youngest sister, Georgetta, was married to another 7th Cavalry officer, Lieutenant Ezra B. Fuller, making Varnum and Fuller brothers-in-law. Charles and Mollie’s marriage produced three children: Georgia Moore was born at Fort Yates in 1887 and died in 1964, Mary Lydia was born at Fort Sill in 1889 and died within a couple of weeks, and John Prescott was born at Fort Riley in 1892 and died sometime after 1944, although the family appears to have cut off all ties with the son in the early 1930s before Colonel Varnum passed away.[12]

In 1895 and 1896, Brigadier General J. W. Forsyth, Varnum’s regimental commander at Wounded Knee, took to correcting the official record regarding the regiment’s actions at Wounded Knee and particularly at the Drexel Mission fight on White clay creek. Forsyth and his aide-de-camp, former 7th Cavalry Lieutenant J. Franklin Bell, took to corresponding with many of the officers present at each battle. Lieutenant Sedgwick Rice wrote to Bell in August 1896 and detailed Varnum’s actions at the close of the Drexel Mission fight. This letter to Bell likely began a series of letters that led to Varnum receiving the Medal of Honor.

Seventh Cavalry Mess

Fort Grant, Arizona, Aug 12 1896.My dear Frank [J. Franklin Bell],

You say “I have gone on the basis that after re-taking the 2d position and driving the Indians away, Varnum then went back to the 3d position again and there remained sometime protecting the crossing of the creek while all the other troops withdrew.” You are right; that is just what he did. Varnum did not withdraw from this 3d position until every thing in front of him had gone to the rear including the two troops of the 9th Cavalry which were in the hills to our left rear, and never did cross the creek. Those are the facts as I remember them and I am sure are correct. Still if there remains any doubt in your mind on the subject Gresham would probably be better able to clear it up than I; he was with Varnum all of the time and as I was a trifle “woozy” in those days it might possibly be that I might make a slight mistake as to detail while he would not be apt to.[13]

In the summer of 1897 Captain Varnum was serving as the Professor of Military Science at the University of Wyoming. Unbeknownst to him, his former lieutenant, Captain John C. Gresham, likely following up on the correspondence between Rice and Bell, submitted a certificate to the Adjutant General’s Office regarding Captain Varnum’s gallant conduct on 30 December 1890 at White Clay Creek and recommended he be awarded a Medal of Honor. Gresham was still assigned to the 7th Cavalry, but was serving as the commandant of the Military Department at North Carolina College. He had received his Medal of Honor two years earlier in March 1895 for his actions at Wounded Knee.

I certify that on December 30th, 1890, in action with Sioux Indians on White Clay Creek, S. D., Captain Charles A. Varnum, 7th Cavalry, did a work of great importance in a manner of uncommon gallantry.

For some time the command of General (then Colonel) James W. Forsyth had been retiring before a superior force, who were so bold and persistent that the only safety lay in withdrawing by detachments. Such was the nature of the country that great loss if not massacre might have fallen on the Seventh Cavalry, had this plan been conducted less skillfully.

At the moment Captain Varnum distinguished himself, the following were the conditions: The fire of “B” and Part of “E” Troops under his direction sweeps effectually ground whose hostile occupation must be disastrous to “G” Troop which according to plan is duly retiring under command of Captain W. S. Edgerly. Lieut. J. D. Mann of Varnum’s line has just been wounded. Closely pressed in spite of the efficient fire just mentioned, Edgerly has lost several men, and to come abreast of Varnum must still measure several hundred yards.

The latter now receives an order to withdraw; and for reasons I have never understood, unless it be the men heard the order when given by the Adjutant, the whole line starts hastily to the rear. Varnum, who, doubtless for better view, has constantly remained in dangerous prominence on horseback, orders the crest to be instantly occupied, rides among the men, who seem somewhat panicky, rebukes or encourages them, and with the assistance of his officers soon restores order and regains the position.

His officers were Lieut. Sedgwick Rice, and myself.

On learning the circumstances a little later, Edgerly and his Lieutenant, now Captain E. P. Brewer, warmly acknowledged the debt they owed for themselves and their men to the judgment and gallantry of Varnum.

The conduct of the latter, in my opinion, evinced not only military ability of a high order but also prompt resolution and bravery that are quite exceptional and entitle him fully to a medal of honor.

As an eyewitness of the events I ask that a medal be awarded to Captain Varnum. It may be proper to state that I have written this paper without suggestion from Captain Varnum or any of the officers whose names are given, and who will doubtless be called as witnesses.[14]

The Adjutant General promptly sent letters to Captain Brewer and Lieutenant Rice, both still with the 7th Cavalry, requesting they provide a narrative description of Captain Varnum’s actions at White Clay Creek. Captain Brewer was serving at Fort Apache, Arizona and did not respond. Lieutenant Rice, serving at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, provided the following response the next week.

In the second position occupied by the first battalion of the 7th Cavalry in that engagement, I was ordered with a platoon of Troop E, 7th Cavalry, to re-enforce the line occupied by Capt. Varnum. On reporting to him I found him very hotly engaged with a force of Indians in his front, who were evidently making an attempt to turn the flank of Captain Edgerly’s position on our right. I had been in position assigned me by Captain Varnum for a short time, when an order was received by him to withdraw to a position in our rear. After the movement had commenced, the Indians made a desperate attack on our line, rendering it necessary to re-occupy the position we had just left. Captain Varnum placed himself in front of his line, ordered a charge, which he led most gallantly, drove the Indians from his front, and by occupying his former position made it possible for Captain Edgerly to withdraw in good order. Throughout the entire time I was with Captain Varnum I was much impressed by his coolness and gallantry. Constantly exposing himself to a hot fire, he led and encouraged his command in a manner which, in my judgment, distinguished him for gallantry of a very high degree.[15]

This photograph of Captain Charles A. Varnum, was taken in 1897 shortly after he received his Medal of Honor by registered mail.[17]

On 14 September 1897 the Secretary of War wrote to Captain Varnum notifying him that by direction of the President he was awarded a Medal of Honor. There was no solemn ceremony in the East Room of the White House, rather Secretary Russell A. Alger informed Varnum that his medal would be mailed to him once engraved.[16]

While on occupation duty at Camp Columbia in Havana, Cuba, still a captain in the 7th Cavalry, Varnum wrote to the Secretary of War on 20 February requesting an appointment as a Colonel commanding one of what he believed would be thirty new infantry regiments. In his letter he provides an outstanding narrative of his twenty-seven years in the 7th Cavalry Regiment.

I learn by the papers that Congress appears to be about to pass a bill for increasing the Army by thirty regiments of infantry and I have the honor to request appointment to the Colonelcy of one of them. I would respectfully call attention to my record as an officer of the Army as my recommendation. I was appointed to the U.S. Military Academy from the state of Florida in 1868 and graduated in 1872 and was recommended for promotion in Artillery, Infantry or Cavalry. I chose the Cavalry and was appointed to the 7th. After a short time in the South on reconstruction duty, I went to Dakota and was engaged on all General Custer’s campaigns up to his death. I was his Chief of Indian Scouts on that campaign and discovered the village that brought on the Custer massacre, and came out of the fight with Maj. Reno. I was wounded in the fight. Prior to this I was on the Stanley Expedition of 1873 and was engaged in action with hostile Indians on Aug. 4th and Aug. 11th, 1873 on the Yellowstone River. I was also on General Custer’s Black Hills exploration of 1874. I was on the Nez Perce Campaign in 1877 and the Cheyenne Campaign of 1878. From this to 1890 I was on various smaller expeditions in Dakota and Montana. I was Regimental Quartermaster for three years viz: 1876 to 1879. I was on the Sioux Campaign of 1890-91 and fought Big Foot when that Indian band was exterminated Dec. 29, ’90, and also fought the Sioux the following day at Drexel Mission on White Clay creek; and for my conduct on this occasion was awarded the Congressional Medal for “most distinguished gallantry in action.” For the part taken by my troop at Wounded Knee Dec. 29th, 1890, Gen’l Schofield, then Commanding the Army, offered us the detail at Fort Sheridan, Ill., and we were sent there in 1892 and were engaged in protecting property during the R. R. troubles of 1894. I remained twenty-three years continuously with my Regiment before I left it for a school detail in 1895. If the 7th Cavalry has a history to be proud of, I think I helped, to some extent, to make it. I am now serving with my Regiment in command of my Troop in this camp.[18]

Captain Varnum fell ill with typhoid fever shortly after making the request for a colonelcy in a new regiment, and never received the position he sought. Varnum was finally promoted to Major in 1901 after twenty-nine years of service and was stationed with the 7th Cavalry. He was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in 1905 and served in Manila with the 4th Cavalry. Over his objection, Lieutenant Colonel Varnum was retired by a medical board in 1907. The physicians found “this officer is a very corpulent man of fifty-eight years of age…” and that he had a defective heart. They went on to conclude that “it is evident that while Colonel Varnum could do ordinary garrison duty for years to come, he is not in good condition for active service in the field.”[19]

Varnum would go on to prove that he was capable of duty for years to come, as he continued to serve the military in the National Guard and Reserves for another twelve years. The day after he was retired, at his request Varnum was assigned as an instructor to the Idaho National Guard. He subsequently served as a Professor of Military Science and Tactics at the University of Maine. In 1912 he was put in charge of military recruiting at Portland, Oregon, and based on his six years of success there, he was put in charge of recruiting at Kansas City. His final assignment as a “retired” Lieutenant Colonel came in September 1918 as the finance and disbursing officer at Fort Mason in San Francisco, California.[20]

Varnum’s final military accolades came in July 1918 when he was promoted to Colonel on the retired list. Three decades after his troop received the full blast of the opening volley at Wounded Knee, the Army again recognized his gallantry from that day with a Silver Star Citation. Varnum was the last soldier recognized with the Medal of Honor for actions during the Pine Ridge Campaign. He was the only officer that was recognized with Honorable Mention and later a Silver Star Citation for actions at Wounded Knee and with a Medal of Honor for actions at White Clay Creek, two separate engagements during the Pine Ridge Campaign November 1890 – January 1891. When he finally retired in 1919 at the age of seventy he had served the military for over forty-seven years, not including his four-year cadetship at West Point.[21]

During his retirement years, Colonel Varnum wrote several drafts of a memoir that were later published in two separate versions. In his own words at the twilight of his life some forty years beyond the battlefield the retired colonel provided additional details of that tragic day at Wounded Knee.

In order to picture the dramatic action that followed, a word of explanation is necessary. Drawn up on the banks of a dry branch was the long Indian line formed in a flat arc, facing the line of the two dismounted troops about fifteen yards away. The squaws and children in the far rear. It was bitterly cold. The warriors’ blankets covered them completely, exposing only their eyes. My first sergeant and I, with a few men, started the search of the left of the line. The first Indian stood up, threw open his blanket showing a belt full of cartridges, but no gun. As I was turning to secure a receptacle for the cartridges, the entire hostile line rose to their feet as one man, turned their backs, shook off their blankets and turning again with the hidden rifles in their hands fired a volley point blank at the troops. The latter was ready, for there was but one deafening crash as Indians and soldiers fired together. The surrounding troops joined the melee as soon as it began. The hostile line wilted and the few survivors disappeared over the bank into the ravine. Unwittingly that one volley of the troops swept through the village and doubtless killed many women and children. Big Foot fell in the cross-fire and I lost my lifelong chum, Captain Wallace, who met his death in the brush where he had gone searching for arms. The toll was heavy on both sides. My troop alone sustained a loss of four killed and seven wounded.[22]

Colonel Varnum and his wife, Mollie, remained in San Francisco in retirement. He passed away on 26 February 1936 and was buried at the San Francisco National Cemetery. His wife joined him in death in 1939. At the time of his death he was the last surviving officer from the Little Bighorn battle and one of only seven from Wounded Knee.[23]

Colonel Charles A. Varnum is buried along with his wife, Mollie Varnum, in the San Francisco National Cemetery.[24]

Endnotes

[1] Adjutant General’s Officer, “7th Cavalry, Troop B, Jan. 1885 – Dec. 1897,” Muster Rolls of Regular Army Organizations, 1784 – Oct. 31, 1912, Record Group 94, (Washington: National Archives Record Administration).

[2] Jacob F. Kent and Frank D. Baldwin, “Report of Investigation into the Battle at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota, Fought December 29th 1890,” in Reports and Correspondence Related to the Army Investigations of the Battle at Wounded Knee and to the Sioux Campaign of 1890–1891, the National Archives Microfilm Publications (Washington: The National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration, 1975), Roll 1, Target 3, Jan. 1891, 667 – 669 (Varnum’s testimony dated 7 Jan 1891).

[3] Muster Roll; Ernest A. Garlington, “The Seventh Regiment of Cavalry,” from The Journal of the Military Service Institution of the United States, Volume 16, edited by James C. Bush, (Governor’s Islands: Military Service Institution, 1895), 663.

[4] National Archives Microfiche Publication M1395, “2260 ACP 1876: Varnum, Charles A.,” Letters Received by Commission Branch, 1874-1894, 330.

[5] Adjutant General’s Office, General Orders, G.O. 100 page 3.

[6] New England Historic Genealogical Society, Massachusetts, Town Birth Records, 1620-1850 [database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 1999; Ancestry.com, 1850 United States Federal Census [database on-line], Year: 1850, Census Place: Troy Ward 6, Rensselaer, New York, Roll: M432_584, Page: 230A, Image: 467; Year: 1860, Census Place: Dracut, Middlesex, Massachusetts, Roll: M653_506, Page: 792, Image: 788, Family History Library Film: 803506; Year: 1870, Census Place: Tallahassee, Leon, Florida, Roll: M593_131, Page: 679B, Image: 760, Family History Library Film: 545630; Year: 1900I, Census Place: Valverde, Arapahoe, Colorado, Roll: 121, Page: 2B, Enumeration District: 0155, FHL microfilm: 1240121; Year: 1910, Census Place: Denver Ward 16, Denver, Colorado, Roll: T624_117, Page: 12A, Enumeration District: 0197, FHL microfilm: 1374130; Historical Data Systems, comp., American Civil War Soldiers [database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 1999, Side served: Union, State served: Massachusetts, Enlistment date: 5 Aug 1862.

[7] Timothy M. Coughlan, “Charles Albert Varnum,” Sixty-seventh Annual Report of the Association of Graduates of the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, June 11, 1936, (West Point: USMA AOG, 1936), 82-90.

[8] Florida Department of State Division of Library & Information Services, “Charles Albert Varnum, Medal of Honor Recipient,” Family Memory, http://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/146174 accessed 2 Nov 2013.

[9] Associated Press, “Incidents of Dakota History are Reviewed,” The Bismarck Tribune, April 08, 1922, page 3.

[10] Associated Press, The Washington Critic, April 23, 1886, page 4.

[11] National Archives Microfiche Publication M1395, “2260 ACP 1876: Varnum, Charles A.,” Letters Received by Commission Branch, 1874-1894, 99.

[12] Riverboat Dave’s Paddlewheel Site, http://www.riverboatdaves.com/riverboats/m-3.html accessed 3 Nov 2013; Associated Press, The Bismarck Tribune, Dec. 3, 1886, page 8; Tenth Census of the United States, 1880. (NARA microfilm publication T9, 1,454 rolls), Year: 1880, Census Place: Billings, Dakota Territory, Roll: 111, Family History Film: 1254111, Page: 48C, Enumeration District: 101, Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29, National Archives, Washington, D.C.; United States of America, Bureau of the Census, Twelfth Census of the United States, 1900, Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1900. T623, 1854 rolls, Year: 1900, Census Place: Denver, Arapahoe, Colorado, Roll: 119, Page: 16A; Enumeration District: 0069, FHL microfilm: 1240119.

John Prescott Varnum appears on 22 Apr 1943 at Tacoma, Washington on a WWII draft registration. He lists no employer and indicates that there is no one who would always know his address. His sister was still alive and living in San Francisco at the time. It appears the family broke off ties with him sometime in the first half of the 1930s. There is no mention of John Prescott Varnum, or a son at all, in Col. Charles A. Varnum’s obituaries in 1936, which do list his wife and daughter. John P. Varnum is carried on the prison rolls and is listed in the 1940 Census as a divorced 48-year-old inmate in California’s Folsom State Prison; his prison enrollment also indicates he was divorced with one child. He was sentenced to a 14 year sentence on 11 Mar 1936 for forgery and writing fraudulent checks and was paroled in 1941. The 31 Dec 1941 edition of the L. A. Times has the following entry: “John P. Varnum has a cute little racket. He pretends to be a Navy commander and visits the homes of Pearl Harbor victims, claims to have known the men and asks for money to get to San Pedro, where he can get his paycheck.” By October 1943 he was again serving time at San Quentin and was paroled 25 Dec 1944 with his sister, Georgie, listed as his family contact.

[13] Sedgwick Rice to J. Franklin Bell dated 12 Aug 1896, James W. Forsyth Papers, 1865-1932, Series I. Correspondence, Box 1, Folder 1 – Box 2, Folder 49, The Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Libraray, Yale University Library.

[14] National Archives Microfiche Publication M1395, “2260 ACP 1876: Varnum, Charles A.,” Letters Received by Commission Branch, 1874-1894, 145.

[15] Ibid., 144.

[16] Ibid., 156.

[17] Ibid., 11-12.

[18] Ibid., 211-213.

[19] Ibid., 388-389.

[20] Coughlan, “Charles Albert Varnum,” 82-90.

[21] Military Times, “Charles Albert Varnum,” Military Times Hall of Valor, http://projects.militarytimes.com/citations-medals-awards/recipient.php?recipientid=365 accessed 3 Nov 2013.

[22] John M. Carroll, ed., Custer’s Chief of Scouts: The Reminiscences of Charles A. Varnum, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1982), 22-23.

[23] Ancestry.com, U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962[database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012, Interment Control Forms, 1928–1962, Interment Control Forms, A1 2110-B, Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774–1985, Record Group 92, The National Archives at College Park, College Park, Maryland.

[24] Carol, photo., “Mary Alice Moore Varnum,” FindAGrave, http://image1.findagrave.com/photos250/photos/2008/93/3544750_120727065380.jpg accessed 2 Nov 2013.

Citation for this article: Samuel L. Russell, “Captain Charles Albert Varnum, Commander, B Troop, 7th Cavalry – Most Distinguished Gallantry,” Army at Wounded Knee, updated 11 Oct 2014, accessed date __________, http://wp.me/p3NoJy-aE.

Very well done, Sam. Exceptional post.

LikeLike

I just received a copy of John M. Carroll’s, Custer’s Chief of Scouts: The Reminiscences of Charles A. Varnum. In the forward, Carroll presents a later account of Wounded Knee that Varnum recorded in an unfinished memoir. It is similar to his testimony presented at the beginning of this post, but has some additional detail. I have added Varnum’s later account of the Wounded Knee battle toward the end of the post.

LikeLike

While reviewing a microfilm of the James W. Forsyth papers that I obtained from teh Beinecke Rare Book Room and Library from Yale, I rediscovered a letter from Lieut. Sedgwick Rice to Lieut. J. Franklin Bell, in which the former details Varnum’s actions at White Clay Creek. As this letter likely led to Varnum being awarded the Medal of Honor, I have updated this post to include Rice’s letter to Bell.

LikeLike