…immediately the whole lot of bucks rose, threw off their blankets, faced about and delivered a volley directed towards K Troop and their own tepees, which were surrounded or occupied by women and children.

First Lieutenant William J. Nicholson, A Troop, 7th Cavalry, at Pine Ridge Agency, Jan. 1891. Photographer L. T. Butterfield, Chadron, Nebraska.

On 29 December 1890 Lieutenant William J. Nicholson was thirty-four and had been with the regiment for over fourteen years. He had been assigned as the First Lieutenant of Captain Nowlan’s I Troop since his promotion in 1884, but was serving as Major S. M. Whitside’s battalion adjutant during the campaign. It was in that capacity that he rode out with Whitside the previous day to demand the surrender of Chief Big Foot and his band of Miniconjou Lakota. Lieutenant Nicholson was the final officer called to testify on the first day of Major General Miles’ investigation into the affair at Wounded Knee. His answers to the court’s questions were documented as follows.

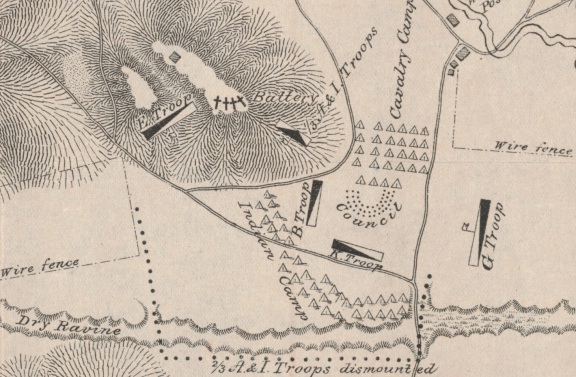

Just before the firing commenced on the part of the Indians on the 29th of December last, Troop K, Captain Wallace’s, was posted by me about 30 paces in rear of the Indian circle of bucks towards the ravine; in other words, facing north and towards the Indian bucks. Troop B was located on the right hand of the circle of Indian bucks perpendicularly to K Troop, about the same distance from the Indians and faced east or towards the general direction of Wounded Knee Creek. I posted G Troop in the position located on the map (which was here handed to the Lieut.) at least 1,000 yards from the circle of Indian bucks. This Troop was mounted and was facing about west and towards the Indians. E Troop was posted, mounted, to the right of the battery, in a little depression of ground, and about 150 yards from the Indian circle facing in a general direction towards the bucks and their village.

Inset of Lieut. S. A. Cloman’s map of Wounded Knee depicting the scene of the fight with Big Foot’s Band, December 29, 1890.

The first thing I saw of a disturbance was in a buck who started up with a handful of dirt, which he threw in the air. I immediately heard a shot fired from the circle. I was about 30 yards off, in the angle between Troops K and B, and then immediately the whole lot of bucks rose, threw off their blankets, faced about and delivered a volley directed towards K Troop and their own tepees, which were surrounded or occupied by women and children. Then the mass of the bucks broke through K Troop and their own tepees into the ravine accompanied by their women and children. Just before the firing took place, I was in rear of the center of the line of tepees on the edge of the ravine with Lieut. Garlington, who was one of the officers on guard, when he remarked to me that the squaws were saddling up and packing and that he was satisfied that they would make a break. He advised me to report the fact to Major Whitside, and I was on my way to him and had reached the opening between B and K Troops when the first shot was fired by the Indians. I then made a break, going in rear of B Troop to a point just behind the crest of the hill to the left of the Battery. I heard several cautions given by officers, and gave some myself, to the soldiers, not to fire on squaws, and remember one particular case; there was an object in the left hand corner of the village moving round on its hands and knees; two or three shots were fired at this object; I got the glasses from Captain Capron, 1st Artillery, and saw that it was an old squaw, and immediately stopped the men from firing, and she came out all right. I heard cautions given all along the line: “For God’s sake don’t fire, she is a squaw.” This in several instances. The first fire of the Indians inevitably endangered the lives of their own women and children; every shot that did not kill a soldier must have gone through their village. I saw several squaws’ bodies after the fight was over, and all were in close proximity to warriors’ bodies. The fire from warriors continued as long as it was possible for them to fire; they even fired after they were wounded and lying on the ground and from the midst of the women and children. I saw many instances of humanity on the part of our men, particularly towards children. I saw one trooper, with a child in his arms, going towards the women, by orders, to deliver it in a place of safety.[2]

In early March 1891, Colonel Forsyth recommended that the Commanding General of the Army recognize five of his lieutenants with honorable mention in general orders for their conduct at Wounded Knee and during the Sioux Campaign. Of the five lieutenants, Robinson, Gresham, Brewer, Tompkins, and Nicholson, only Gresham received honorable mention and ultimately a Medal of Honor. Major General Schofield’s decision to not recognize the other four lieutenants likely stemmed from General Miles’ recommendations in December 1891, after having his inspector general, Colonel Edward M. Heyl, investigate the campaign for acts of valor.[3]

William Jones Nicholson was born on 16 January 1856 at Washington, District of Columbia, the second son of U.S. Naval officer Somerville Nicholson (b. 1822 – d. 1905) and Hannah Maria Jones (b. 1837 – d. 1897). Somerville Nicholson at that time was serving as a lieutenant on ordnance duty at the Washington Navy Yard. In addition to their son, William Jones, the Nicholsons had six other children all born in the Nation’s capitol: Reginald Felix (b. 1852 – d. 1939), Mrs. Helen Cooke (b. 1860 – d. 1935), Augustus Somerville (b. 1862 – d. 1936), Henry William Ducachet (b. 1864 – d. 1913), Mrs. Mary Blake Matthews (b. 1866 – d. 1921), and Reynolds Lispensard (b. 1871).[4]

Raised and educated in Washington, D.C., Nicholson desired a commission in the army, and family connections served him well. In a letter dated 11 August 1875 to President U. S. Grant, Dr. John B. Blake, Secretary of the Washington National Monument Society, recommended the nineteen-year-old Nicholson for a commission in the army.

Understanding that there are a number of appointments of Second Lieutenants soon to be made in the army I respectfully recommend my young friend, Mr. Wm. J. Nicholson of this District, as peculiarly fitted for that branch of the public service, especially cavalry, possessing as he does a fine physique, great activity, a liberal education and promising talents. He is a son of Capt. S. Nicholson of the Navy and a nephew of Mr. W. W. Corcoran, who I am satisfied, but for his absence from the city, would cordially unite with me in this application. His grandfather, the late Dr. Wm. Jones, was my preceptor and partner, and hence I feel a personal favor. I place this application on personal grounds because of the confidence you manifested in me by tendering me an appointment on the board of public works for this District, which, however unfortunately it eventuated for me, I shall ever hold in proud and grateful recollection.[5]

President Grant acted on the recommendation, and in August 1876, William Nicholson was commissioned from civil life at the age of twenty. The young Second Lieutenant was assigned to B Troop, 7th Cavalry, and ordered on detached service to the Cavalry Depot at Saint Louis, Missouri, ostensibly to take charge of recruits and deliver them to Fort Abraham Lincoln, Dakota Territory, but more than likely to receive at least some rudimentary military training before reporting to his first duty station. Nicholson arrived at Fort Lincoln in October and immediately joined his company in the field it was the beginning of almost four decades with the 7th Cavalry Regiment.[6] Despite the lack of formal military training, neither through West Point nor enlisted service, the young Nicholson acquitted himself well during the remainder of the Little Big Horn Campaign of 1876-’77. Captain Frederick Benteen, a difficult officer to impress, was nonetheless moved by Nicholson’s actions at Canon Creek. He was one of three lieutenants that Benteen gave honorable mention to in his official report.

The gallant charge into and beyond Canon Creek made by this battalion against the Nez Perce Indians led by Chief Joseph and the charge through the gap held by the same Indians in the afternoon of the same day will ever be memorable in the history of Indian fighting and was of such quality as to draw praise and commendation from the detachment of the battalion of the First United States Cavalry, who witnessed the charges.

First Lieut. George D. Wallace, Seventh Cavalry, commanding Troop G, Lieut. John C. Gresham and Lieut. W. J. Nicholson, Seventh Cavalry, are especially recommended for gallantry, dash, and devotion to duty exhibited by them.[7]

Nicholson’s most impressive, or at least his most recognized, military performance came at the twilight of his career when as a sixty-two-year-old National Army brigadier in command of the 157th Infantry Brigade during the Great War, he was awarded a Silver Citation, a Distinguished Service Medal, and eventually a Distinguished Service Cross for his performance during one of the final offensives of the war. His citation is all the more astounding considering his advanced age.

…for extraordinary heroism in action while Commanding the 157th Infantry Brigade, 79th Division, A.E.F., near the Bois-de-Beuge, Montfaucon, France, 29 September 1918. General Nicholson established and maintained his brigade post of command on an exposed elevation near the Bois-de-Beuge, in order that he might effectively direct the attack of his brigade upon the Madeleine Farm and its surrounding woods. Realizing the importance of increased artillery support, he personally visited the division post of command behind Montfaucon to seek such support. In his absence the brigade post of command open to enemy observation was swept by a concentration of enemy machine-gun fire and artillery fire. In the face of this terrific fire General Nicholson, with great coolness and with complete disregard for his own safety, rode forward on horseback to his brigade post of command to issue orders for the renewed attack upon the Madeleine Farm, supervising the formation for attack, and by his brave and gallant example inspired the men of his command with renewed courage and determination, which enabled them to reach their objective and hold it against repeated enemy counterattacks.[8]

Nicholson retired in 1920 by requirement of law at age sixty-four. He was eventually promoted to Brigadier General from the retired list in 1927. He died on 20 December 1931, and an obituary in the New York Times paid tribute to the veteran cavalry officer and four and a half decades of service in the saddle.

Washington, December 20. Brigadier General William J. Nicholson, United States Army, retired, who commanded the Maryland troops in the World War, died tonight at his apartment here after a brief illness in his seventy-sixth year. Funeral services will be held in St. Matthew’s Catholic Church on Tuesday morning. Burial will take place in Arlington Cemetery.Brigadier General William J. Nicholson, National Army, in 1918 while commanding the 157th Infantry Brigade during the First World War.[10]

General Nicholson was born in Washington on January 16, 1856. His father was Commodore Somerville Nicholson, United States Navy. The son was commissioned a Second Lieutenant of Cavalry in 1876. After graduating from the Infantry and Cavalry School in 1883, he served in the Spanish-American War and later in the Mexican punitive expedition. As Commander of the Maryland troops he participated in the Meuse-Argonne offensive and other battles.

The Distinguished Service Medal was awarded to him. He was an Officer of the Legion of Honor. He was promoted to the rank of Brigadier General in the regular Army by an Act of Congress on February 27, 1927. He married Miss Harriet Fenlon of Wichita, Kansas in 1883. They have had a son and a daughter.

Of the forty three years of his continuous service in the Army, General Nicholson, who retired in January 1920 spent thirty seven with the Seventh Cavalry, General Custer’s old Regiment, which he commanded for a time. The Distinguished Service Cross awarded him in April 1919 was in recognition of distinguished and exceptional gallantry at Bois de Bouge on September 19, 1918. He received the Distinguished Service Medal in the same year, 1919. He is said to have had a wider experience with enlisted men than any other American officer.

At the outset of the World War General Nicholson had charge of the Officers’ School at Fort Sheridan, where he prepared for their commissions many young Chicagoans. In 1917 he was in command at Camp Meade. Overseas he led the Brigade of the Seventy-ninth Division that included the 313th and 314th Infantry. With these troops he captured Montfaucon and then moved over to the Verdun sector, where he was stationed at the Armistice. On his return to the United States he held command of Camp Upton during the period of demobilization in 1919.

In September 1920 General Nicholson was elected President of the Army and Navy Club of America. He held that office when, the following February, the club acquired the clubhouse at 112 West Fifty-ninth Street, formerly occupied by the German Club. He was also a member of the Chevy Chase Club of Washington.[9]

Brigadier General William J. Nicholson and his wife, Harriet Fenlon, are buried in Arlington National Cemetery.[10]

Endnotes:

[1] L. T. Butterfield, photo., cropped from “Officers of the 7th Cav. at P.R. Agc. S.D.,” Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, http://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3432005 accessed 11 Oct 2013.

[2] Jacob F. Kent and Frank D. Baldwin, “Report of Investigation into the Battle at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota, Fought December 29th 1890,” in Reports and Correspondence Related to the Army Investigations of the Battle at Wounded Knee and to the Sioux Campaign of 1890–1891, the National Archives Microfilm Publications (Washington: The National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration, 1975), Roll 1, Target 3, Jan. 1891, 669 – 671 (Nicholson’s testimony dated 7 Jan 1891).

[3] Adjutant General’s Office, Letter to Major General Nelson A. Miles dated 2 Oct 1891, The Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, James W. Forsyth Papers, 1865-1932, (New Haven: Yale University Library), Series I, Correspondence, Box 1, Folder 1 – Box 2, Folder 49.

[4] Ancestry.com, 1870 United States Federal Census [database on-line], Census Place: Georgetown, Washington, District of Columbia, Roll: M593_127, Page: 553B, Image: 104, Family History Library Film: 545626; United States Congress, Reports of Committees of the Senate of the United States for the First and Second Sessions of the Forty-sixth Congress 1879-’80, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1880), 74.

[5] John Y. Simon, ed., The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Vol. 26: 1875, (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2003), 268-269.

[6] National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Washington, D.C., Returns from U.S. Military Posts, 1800-1916, Microfilm Serial: M617, Microfilm Roll: 628.

[7] United States Congress, “Promotion of Certain Officers,” Hearings Before a Subcommittee and the Committee on Military Affairs, House of Representatives, Sixty-seventh Congress, Second Session, on H.R. 10349, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1922), 13.

[8] Military Times Hall of Valor, “William John Nicholson,” http://projects.militarytimes.com/citations-medals-awards/recipient.php?recipientid=15684 accessed 12 Oct 2013. Nicholson’s middle name is sometimes shown as John and sometimes as Jones. I have found no definitive document, such as a birth certificate or christening document to settle the matter. Most documents list only his middle initial. I have listed his middle name as Jones, as that was his mother’s maiden name.

[9] Associated Press, “Brigadier General Nicholson Dies in 76th Year,” New York Times, 21 Dec 1931.

[10] History Committee 79th Division Association, History of the Seventy-ninth Division A.E.F. During the World War: 1917-1919, (Lancaster: Steinman & Steinman, 1922), 188.

[11] Edward Tyler, photo., “Gen William Jones Nicholson,” FindAGrave, http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=pv&GRid=23535669&PIpi=9556038 accessed 13 Oct 2013.

Citation for this article: Samuel L. Russell, “Lieutenant William Jones Nicholson, Adjutant, 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry,” Army at Wounded Knee, posted 13 Oct 2013, accessed date __________, http://wp.me/p3NoJy-cB.

![Brigadier General William J. Nicholson, National Army, in 1918 while commanding the 157th Infantry Brigade during World War I.[10]](https://armyatwoundedknee.files.wordpress.com/2013/10/brig-gen-wm-j-nicholson-157th-inf-brig.jpg?w=246&h=300)