If Forsyth was relieved because some squaws were killed, somebody had made a mistake, for squaws have been killed in every Indian war. –General William T. Sherman, U.S. Army, Retired

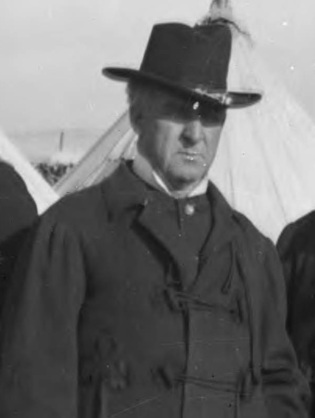

Major General Nelson Appleton Miles, January 13, 1891, cropped from G. E. Trager’s “Gen Miles and Staff during Late Indian War at Pine Ridge Agcy.”

Major General Nelson A. Miles, Commander of the Division of Missouri, telegraphed Major General John M. Schofield, Commander-in-Chief of the Army, on December 30, 1890 detailing all that he knew of the battle at Wounded Knee Creek. It was incomplete information. In his message, Miles does not appear to be displeased with the 7th Cavalry’s performance or the outcome of the battle indicating that, “their [the warriors’] severe loss at the hands of the 7th Cavalry may be a wholesome lesson to the other Sioux. . . . Their getting so near the Pine Ridge Agency just at this time has complicated the surrender of all the hostiles in the Bad Lands, which would have been consummated before this had it not occurred; still the severity of their loss at the hands of the troops may possibly bring favorable results.” Schofield replied, “Your dispatch . . . further encourages my hope and belief that you will soon master the situation. Give my thanks to the brave 7th Cavalry for their splendid conduct.”[1]

When General Miles sent his report to General Schofield he was unaware of the extent of the 7th Cavalry’s casualties. En route from Rapid City to Pine Ridge, Miles spent much of the afternoon and the night of December 30 at Chadron, Nebraska. Late in the evening he learned of the number of troopers killed and wounded the previous day, perhaps from newspaper accounts. Bad news did not age well with Miles, and he was livid that his subordinates had not informed him of all they knew, particularly since this lack of information made Miles’ report to Schofield incomplete at best, and deceptive at worst. Firing off a telegram at 10:30 p.m. to Brigadier General John R. Brooke, commanding the Department of the Platte and all forces at the Pine Ridge Reservation, Miles was curt with Brooke, “I hear that twenty-five men were killed and thirty-four wounded in fight with Seventh Cavalry. Some one seems to be suppressing facts. I have made my report to the Adjutant General of the Army on what is received regarding skirmish between Forsyth and Indians. State position of Forsyth’s command and also the other troops.” The newly learned facts clearly altered Miles’ view of the effect that Wounded Knee had on the other Indians. Where he reported to Schofield that the Indians’ severe loss may bring favorable results, Miles telegram to Brooke stated, “Whatever the circumstances of that fight with Big Foot may be it must have had the effect of increasing the hostile element very largely.”[2]

Clearly on the defensive Brooke responded thirty minutes later, “Your telegram about losses is not understood.” Realizing his error Brooke continued, “Yesterday Forsyth lost Captain Wallace and twenty-four men of the Seventh Cavalry and one Indian scout killed and Lieutenants Garlington, 7th Cavalry, and Hawthorne, 2nd Artillery, and thirty-six men wounded in the fight with Big Foot. I was sure I reported this to you last night, but it seems I did not, but sent it to General Ruger.” He offered his superior his apologies, “I regret that there was a mistake in sending to General Ruger the information which should have gone to you,” and then tried to smooth any ruffled feathers, “I feel that everything is going well here.” Brooke concluded his response with an excuse for half-measures, “I did telegraph you at 9:25 last night that Forsyth had about seventy killed and wounded.”[3]

General Brooke’s telegram from the previous evening was vague and the number of casualties listed appeared to refer to Indian casualties, not soldiers. Was Brooke’s failure to report to Miles an act of omission, or commission? The telegram he sent to General Thomas H. Ruger, commanding the Department of Dakota, the evening of December 29 was thorough and detailed the most accurate casualty numbers available at the time. So too was a similar telegram that Brooke sent to his own adjutant general at Fort Omaha. Brooke had been in almost constant telegraph communication with Miles throughout the day, but the telegram to Ruger was the only one sent from Brooke on the 29th. Perhaps Brooke was reluctant to send the startling casualty numbers to Miles and instead forwarded his report to Ruger in hopes that he would pass on the tragic numbers to their superior officer. Following the campaign, Brooke twice indicated that he thought in general that he should report to Ruger, as the disturbances were all within the territory of the Dakota department. However, Brooke’s correspondence throughout November and December 1890 demonstrates that he regularly reported to Miles, not Ruger. Intentional or not, Brooke’s failure to report accurate casualty numbers to Miles in a timely manner created, or at least added to, the negative view that the commanding general was developing toward the tragic outcome of Wounded Knee.

That night, December 30, Miles wrote a letter to his wife, Mary, the niece of the former commander-in-chief of the Army, Lieutenant General William T. Sherman, in which he did not hide the displeasure he felt toward his subordinates. “Two nights ago I thought I had the whole difficulty in my hand, and without the loss of a single life. But all my efforts to prevent a war appear to have been destroyed by the action of Lt. Col. [Edwin V.] Sumner and Col. [James W.] Forsyth.”[4]

General Miles’ ire turned exclusively toward Forsyth as the newspapers began circulating stories that sensationalized the battle and voiced severe criticism of the killing of non-combatants, some characterizing the affair as a “slaughter of innocents.” Many of these same papers leveled their criticism directly at the commanding general. For an ambitious man such as Nelson Miles, any negative publicity of his campaign was a personal attack on his character, an unjust attack for which he felt James Forsyth’s actions were to blame. By the first of the new year, Miles was sure that Forsyth’s handling of the entire incident was incompetent, if not criminal.[5]

On January 1, 1891, Miles telegraphed Schofield.

Your telegram of congratulations to the 7th Cavalry received, but as the action of the Colonel commanding will be a matter of serious consideration, and will undoubtedly be the subject of investigation, I thought it proper to advise you. In view of the above fact, do you wish your telegram transmitted as it was sent? It is stated that the disposition of four hundred soldiers and four pieces of artillery was fatally defective and large number of soldiers were killed and wounded by the fire from their own ranks and a very large number of women and children were killed in addition to the Indian men.[6]

The next day General Schofield concurred with Miles’ recommendation stating, “. . . please withhold it until further advised by me.” Later that day, Schofield passed Secretary Proctor’s instructions on to Miles.

He [the president] hopes that the report of the killing of women and children in the affair at Wounded Knee is unfounded, and directs that you cause an immediate inquiry to be made and report the results to the Department. If there was any unsoldierly conduct, you will relieve the responsible officer, and so use the troops engaged there as to avoid its repetition.[7]

Miles wasted no time in preparing for an investigation into Forsyth’s actions, and in fact had already set the wheels in motion the previous day by instructing Captain F. A. Whitney, 8th Infantry, to examine the battlefield and determine how many Indians were killed and wounded. Miles sent orders late on the night of January 2 for Major S. M. Whitside to accompany a burial party to Wounded Knee and assist the acting division engineer in making a detailed map of the battleground showing exact troop positions. Miles also sent his assistant inspector general, Major J. Ford Kent, and perhaps his closest protégé, Captain Frank D. Baldwin, to observe the battlefield and oversee Whitside’s work on the desired map. Whitside spent the next two days with Lieutenant Sydney A. Cloman, Acting Engineer Officer for the Division of the Missouri, detailing every aspect of the battlefield. While Whitside and Cloman surveyed the ground, a burial party went about the gruesome work of collecting the frozen Indian corpses and dumping them unceremoniously into a ditch where they were buried at a rate of two dollars a body.

![[]](https://armyatwoundedknee.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/1004799_quarter-copy.jpg?w=640&h=375)

(Click to enlarge) Chief Big Foot’s frozen body on January 3, 1891. Pictured in the background are from the left to right Lieutenant S. A. Cloman, Major J. F. Kent, Major S. M. Whitside, and a surveying party.[8]

Captain Folliott A. Whitney reported the number of Indian casualties remaining on the battleground on January 3, five days after the incident.[9]

Camp U.S. Troops.

Rosebud Crossing, Wounded Knee Creek,

January 3, 1891.Acting Assistant Adjutant General.

Department of the Platte,

Pine Ridge Agency, S. D.Sir: In compliance with instructions contained in your letter of January 1st, 1891, I have the honor to report that I have examined the ground where the fight with Big Foot’s band occurred, and counted the number of Indians killed and wounded, also number of ponies and horses with the following result:

82 bucks and 1 boy killed, 2 bucks badly wounded, 40 squaws killed, 1 squaw wounded, one blind squaw unhurt; 4 small children and 1 papoose killed, 40 bucks and 7 women killed in camp; 25 bucks, 10 women and 2 children in the canon [sic] near and on one side of the camp; the balance were found in the hills; 58 horses and ponies and 1 burro were found dead.

There is evidence that a great number of bodies have been removed. Since the snow, wagon tracks were made near where it is supposed dead or wounded Indians had been lying. The camp and bodies of the Indians had been more or less plundered before my command arrived here. I prohibited anything being removed from the bodies of the Indians or the camp.

I have not furnished a sketch or map of camp or vicinity, as Major Whitside arrived about noon to-day and informed me had an officer with him for this purpose.

Very respectfully, Your obedient servant,

F. A. Whitney,

Captain, 8th Infantry, Commanding Camp.[10]

In all the burial party interred 146 Indians at a cost to the government of $292. All the while, photographers recorded for posterity, the horrifying images of dead Indians frozen in their death throes. The slain Indians appeared even more grotesque as photographers turned their stiff corpses over, and in some cases posed them with weapons.

(Click to enlarge) This grisly photograph, advertised as being the medicine man seen as responsible for the carnage, was taken on January 1st, a day prior to the burial and survey parties. Carl Smith of the Chicago Inter-Ocean provided a description for his readers, “He had originally fallen on his face, and he must have lain in that position for some time, as it was flattened on one side. His hands were clenched, his teeth were clenched, and his body seemed to have a tense appearance. One hand was raised in the air. The arm had frozen in that position.” The rifle was likely posed next to the body.[11]

Whitside returned to the agency the following evening only to discover that he was now commanding the regiment. Miles’ aide-de-camp had delivered an order to Colonel Forsyth earlier in the day. “By direction of the President, you are hereby relieved from your present command, pending the inquiry to be made concerning the affair on Wounded Knee.” The same day Miles also issued orders establishing a board of inquiry to look into four charges against Forsyth.[12]

Headquarters Division of the Missouri, In the Field,

Pine Ridge, S.D., January 4, 1891.Special Orders No. 8.

1. In order to comply with the telegraphic instructions of the President of the United States Colonel E. A. Carr, 6th Cavalry, Major Jacob F. Kent, 4th Infantry, A.I.G., and Captain Frank D. Baldwin, 5th Infantry, A.A.I.G., are hereby directed to make an immediate inquiry into, and examination of, all the circumstances and acts connected with the disarming of a band of Indians by troops under the command of Colonel James W. Forsyth, 7th Cavalry, encamped on Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota, December 29th 1890.

They will ascertain whether the disposition made of the troops was judicious, and such as should be made to prevent unnecessary destruction of life while disarming the Indians, and whether the troops were so placed as to make their power most effective in case of resistance.

They will also ascertain whether any non-combatants were unnecessarily injured or destroyed, and whether orders that have been given, prohibiting commanding officers from allowing their commands to be mixed up with armed bodies of Indians, have been complied with.

They will render a full report of what was done with or by the commands in that affair, putting the result of their examination in such form as to render full and impartial justice to all concerned, and sustain the character and integrity of the service.

By command of Major General Miles:

Marion P. Maus, 1st Infantry,

Aide-de-camp.[13]

Miles notified Schofield the following day that he had relieved Forsyth, and inquired if his proposed inquiry met the President’s intentions. After discussing the matter with Proctor, Schofield fired back a message stating, “I am directed by the Secretary of War to inform you that it was not the intention of the President to appoint a court of inquiry…. You were expected yourself first to inquire into the facts and in the event of its being disclosed that there had been unsoldierly conduct, to relieve the responsible officer.”[14]

The relief of Colonel Forsyth and an investigation into Wounded Knee created a furor across the officer corps over action taken against a commander in the field while active campaigning continued, and the confusion over who directed the relief, played out in newspapers across the country. On January 5 the Evening Star ran an article detailing the atmosphere in the Nation’s capital over Forsyth’s relief.

The relief of Col. Forsythe [sic] of his command of the seventh cavalry by Gen. Miles, which has been telegraphed east from unofficial sources, forms the prevailing topic of conversation around the War Department today. It is being talked about with a vigor and an openness of criticism that reminds old timers of the war times, when shuch troubles were frequent. One officer said to a Star reporter: “At this rate the Sioux troubles will grow to be just as bad as events of the first three years of the [Civil] war, when every officer with an independent command had not only an enemy in front of him but a court-martial behind him.”

Officers say that it was a grave error to order the relief of Col. Forsythe at this stage of the proceedings, and thus hold up a warning finger to every colonel in the little army around Pine Ridge, to tell them that the death of each Sioux must be explained. It will have, it is openly asserted, a very demoralizing effect upon the enterprising bravery of the commanding officers in the field, and there are predictions that with the example that is being made of Col. Forsythe in full view there will hardly be a man in the army with any responsibility who will dare to do anything but take part in a negative campaign.

The true inwardness of Gen. Miles’ action in relieving Col. Forsythe has not yet come to light, but it is generally believed that this course was inspired by the officials here. Neither Secretary Proctor nor Gen. Schofield are willing to say very much on the subject, although both practically admit that Gen. Miles did not act entirely upon his own responsibility. Secretary Proctor said to a Star reporter: “Gen. Miles did it. It is a very much mixed up matter and I may explain it later.”[15]

Despite the apparent blunder in relieving Forsyth before determining the facts, Miles was not about to reinstate the cavalry colonel unless explicitly directed. On January 6, the day before the investigation began, Miles privately aired his low opinion of Forsyth in a letter to his wife. “Forsyth’s actions [are] about the worst I have ever known. I doubt if there is a Second Lieutenant who could not have made better disposition of 433 white soldiers and 40 Indian scouts, or could not have disarmed 118 Indians encumbered with 250 women and children.”[16] That same day he also relieved Colonel Carr from the board of inquiry owing to his continued active roll in containing the outbreak that was still ongoing. This left just Major Kent and Captain Baldwin on the board, creating an irregularity with both officers being junior to Colonel Forsyth. Had the outcome of the board resulted in formal charges and a general court martial against Forsyth, his defense certainly would have challenged the validity of the inquiry.

Headquarters Division of the Missouri In the Field,

Pine Ridge, S.D., January 6, 1891.Special Orders No. 10.

4. Colonel Eugene A. Carr, 6th Cavalry, is hereby relieved from the operations of Paragraph 1, Special Orders No. 8, current series, these Headquarters, and will continue on his present duties.

5. Major Jacob F. Kent… and Captain Frank D. Baldwin… will proceed with the investigation contemplated… which will be conducted under the requirements of Army Regulations 945-946 of 1889.

By command of Major General Miles;

H.C. Corbin, Assistant Adjutant General.[17]

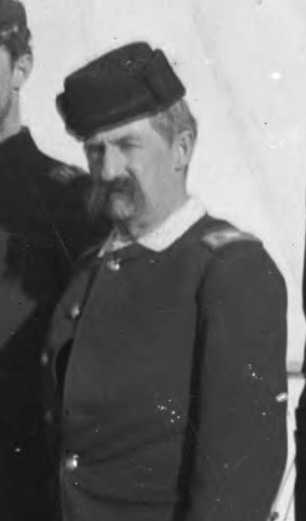

Major Jacob Ford Kent, January 13, 1891, cropped from G. E. Trager’s “Gen Miles and Staff during Late Indian War at Pine Ridge Agcy.”

Major Jacob Ford Kent was a fifty-five-year-old infantry officer that had served continuously since graduating from the Military Academy in 1861. His service during the Civil War spanned from first Bull Run to the Siege of Petersburg. Kent was wounded in two engagements, captured in one, and awarded with brevets for gallantry twice, finishing the war as a captain in the 3rd Infantry with a brevet rank of lieutenant colonel. Following the war, he taught tactics at West Point for four years. He continued service with the 3rd on the frontier at posts from Fort Lyons, Colorado, to Fort Missoula, Montana. In 1885, Kent was promoted to major in the 4th Infantry and had served in that capacity at Fort Omaha, Nebraska, up to the campaign of 1890. Major Kent had served on numerous assignments as an assistant inspector general, his role during the Pine Ridge Campaign. Prior to the conclusion of the Wounded Knee investigation, Kent was promoted to lieutenant colonel in the 18th Infantry.[18]

Captain Frank Dwight Baldwin, January 13, 1891, cropped from G. E. Trager’s “Gen Miles and Staff during Late Indian War at Pine Ridge Agcy.”

Captain Frank Dwight Baldwin was a forty-eight-year-old officer on General Miles’ staff as the inspector of small arms practice. Assigned to the 5th Infantry, Miles’ former regiment, Baldwin had long been a confidant of the major general. The captain was a native Michigander, the state from which he entered the Volunteers during the Civil War. He distinguished himself several times in combat, particularly in action at Peach Tree, Georgia, in 1864, again at McClellan’s Creek and Red River, Texas, in 1874, and at Wolf Mountain, Montana, in 1877. For the first two engagements he was eventually awarded two Medals of Honor, the first issued in December 1891 while working on Miles’s staff. Baldwin was also awarded a brevet to captain for gallantry at Red River, and for the Wolf Mountain engagement, he was awarded a brevet promotion to major for gallantry. General Miles likely played a role in all four accolades, and personally made the recommendations for one of the Medals of Honor and both brevet promotions. Baldwin had been with the 5th Infantry since 1869 and a captain since 1879. For the purposes of the Wounded Knee inquiry, General Miles appointed Baldwin an acting assistant inspector general at the beginning of January 1891, an appointment Miles made just three days after the Wounded Knee Creek affair, and the day before he was instructed to look into “any unsoldierly conduct,” leading some officers to conclude that Miles was stacking the deck with officers more likely to render findings in accordance with the commanding general’s wishes than in rendering “full and impartial justice.”[19]

George E. Trager’s “Gen Miles and Staff during Late Indian War at Pine Ridge Agcy,” January 13, 1891. From left to right are Captain Ezra P. Ewers, Lieutenant John S. Mallory, Captain Francis E. Pierce, Lieutenant Colonel Dallas Bache, Captain Francis J. Ives, Major Jacob Ford Kent, Lieutenant Colonel Henry C. Corbin, Major General Nelson A. Miles, Captain Frank D. Baldwin, Lieutenant Sydney A. Cloman, Captain Charles F. Humphrey, and Captain Marion P. Maus. General Miles was the commanding general of the Division of the Missouri.[20

Many in the military circles believed the action Miles was taking against Forsyth was unjustified. Major Whitside wrote to his wife, “The settlement of the Indian trouble has been a failure according to the plans arranged by Gen. Miles, and now some one must shoulder the responsibility and be sacrificed and from appearances Gen. F[orsyth] is the man selected, for other people to unload on.” Forsyth recognized the scrutiny he faced in a letter to his daughter writing her, “From the time I got here I knew that some one would be selected as a scapegoat, for the character of the general officer running this thing indicated this, but I did not believe that I was to be selected by Providence to carry the load.” Some of the criticism came closer to Miles’ own home. The retired Commanding General of the Army, William T. Sherman, wrote on January 7 to his niece, who was also Miles’ wife, “If Forsyth was relieved because some squaws were killed, somebody had made a mistake, for squaws have been killed in every Indian war.” Sherman’s comment was not to insinuate that killing non-combatants was acceptable but rather to reinforce that no commander during the Indian Wars had been held accountable for the unavoidable deaths of women.[21]

That General Miles had already formed his opinion of what transpired at Wounded Knee before his investigation even began can be seen in a letter he wrote to the adjutant general of the army on January 5, 1891. He stated in part:

The report of Colonel Forsyth and accompanying map shows what dispositions he made, and the map, presents one erasible [sic] fact, namely, the commands were so placed that the fire must have been destructive to some of their own men, while other portions of the troops were so placed as to be non-effective. It also appears that after a large number of their arms (47) had been taken away from the Indians, the fight occurred between the troops and Indians in close proximity. The additional map places the troops in somewhat different position. These positions were indicated by Major Whitside, 7th Cavalry as at [the] time [the] fight commenced. Captain Wallace was killed with a war club, others were stabbed with knives, and bows and arrows were used.

The number of casualties were Captain Wallace and 24 men killed, Lieutenants Garlington, Gresham and Hawthorne and 33 men wounded. There were 82 Indian men killed and 64 women and children killed and buried on the ground, and four have since died of wounds, 30 Indians, including men, women and children, some wounded have reached the hostile camp on White Clay Creek, eight men, eleven women and sixteen children, all wounded and thirty women and children not wounded were brought to this place. Another body of Indians, numbering 63, 20 of whom were men, were captured on American Horse Creek, 25 miles from Wounded Knee by 15 scouts, and brought to this camp and disarmed without casualties occurring.

While the fight was in progress with Colonel Forsyth’s command, about 150 Brule Indians left camp then en-route from the Bad Lands to this agency, and went down to the assistance or rescue of the Big Foot Indians. The troops had then become widely separated in chasing the Indians, and this band of Brules attacked Captain Jackson, and recaptured 26 prisoners.[22]

Major J. Ford Kent and Captain Frank D. Baldwin began their investigation on January 7, 1891 by taking sworn testimony from officers and depositions from witnesses. Following was the evidence compiled by the board including the order in which the officers appeared before the two investigators.

Colonel James W. Forsyth’s field reports dated December 28, 29 and 31, 1890.

Major Samuel M. Whitside’s field report dated January 1, 1891.

First Lieutenant Sydney A. Cloman’s map of the Wounded Knee battlefield dated about January 5, 1891.

January 7, 1891 testimony: Major Samuel M. Whitside, Captain Myles Moylan, Captain Charles A. Varnum, First Lieutenant William J. Nicholson.

January 8, 1891 testimony: Captain John Van R. Hoff, Captain Edward S. Godfrey, Second Lieutenant Sedgwick Rice, First Lieutenant Charles W. Taylor.

January 9, 1891 testimony taken at camp on White Clay Creek: Captain Charles S. Ilsley, Captain Henry Jackson, Captain Winfield S. Edgerly, First Lieutenant William W. Robinson, Jr., Second Lieutenant Thomas Q. Donaldson, Second Lieutenant Selah R. H. Tompkins.

January 10, 1891 testimony: Captain Allyn Capron, Captain Henry J. NowlanCaptain Henry J. Nowlan, First Lieutenant Loyd S. McCormick, Captain Charles B. Ewing.

January 11, 1891 testimony: Major Samuel M. Whitside, Colonel James W. Forsyth.

Depositions: Scout Philip H. Wells, Frog (translated by Wells), Help Them, Father Francis M. J. Craft.

January 13, 1891 initial findings.

Colonel James W. Forsyth letter detailing experience in Indian engagements.

January 17, 1891 testimony: Brigadier General John R. Brooke.

January 18, 1891 final findings.

January 31, 1891: Major General Nelson A. Miles endorsement.

February 4, 1891: Major General John M. Schofield endorsement.

February 12, 1891: Secretary of War Redfield Proctor decision.

Endnotes

[1] National Archives “Sioux Campaign, 1890-91,” 635, 636, and 641.

[2] Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Sioux Campaign 1890-91, vols. 1 and 2 (Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1919), 692.

[3] Ibid., 693.

[4] Peter R. DeMontravel, The Career of Lieutenant General Nelson A. Miles from the Civil War through the Indian Wars, (PhD diss, St. John’s University, Ann Arbor: University Microfilms International, 1983), 360.

[5] James W. Forsyth, “Statement of Brigadier General James W. Forsyth, U.S. Army, concerning the investigations touching the fights with Sioux Indians, at Wounded Knee and Drexel Mission, near Pine Ridge, S. D., December 29 and 30, 1890,” in Reports and Correspondence Related to the Army Investigations of the Battle at Wounded Knee and to the Sioux Campaign of 1890–1891, the National Archives Microfilm Publications (Washington: The National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration, 1975), Roll 2, Target 4, Sep. 1, 1895 – Dec. 21, 1896, 7.

[6] National Archives “Sioux Campaign, 1890-91,” 785.

[7] DeMontravel, Lieutenant General Nelson A. Miles, 359.

[8] L. T. Butterfield, photo., “Big Foot. Dead,” Deadwood Pictorial Works, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, New Haven (http://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3432007) accessed 27 Jul 2014.

[9] Samuel L. Russell, “Selfless Service: The Cavalry Career of Brigadier General Samuel M. Whitside from 1858 to 1902,” Masters Thesis, (Fort Leavenworth: U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 2002), 144.

[10] National Archives “Sioux Campaign, 1890-91,” 824 (Whitney’s report dated 3 Jan 1891).

[11] L. T. Butterfield, “The Medicine Man taken at the Battle of Wounded Knee, S.D.” (Chadron, Neb.: Northwestern Photographic Co., 1 Jan 1891), from Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, New Haven (http://brbl-dl.library.yale.edu/vufind/Record/3432008) accessed 27 Sep 2015; Carl Smith, Chicago Inter-Ocean, 7 Jan 1891, from Richard E. Jensen, R. Eli Paul, John E. Carter, Eyewitness at Wounded Knee (Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1991), 110.

[12] Jacob F. Kent and Frank D. Baldwin, “Report of Investigation into the Battle at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota, Fought December 29th 1890,” in Reports and Correspondence Related to the Army Investigations of the Battle at Wounded Knee and to the Sioux Campaign of 1890–1891, the National Archives Microfilm Publications (Washington: The National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration, 1975), Roll 1, Target 3, Jan. 1891, 653-654. Hereafter abbreviated RIBWKC.

[13] Ibid.

[14] National Archives “Sioux Campaign, 1890-91,” 828 (telegram from Schofield to Miles dated 6 January 1891).

[15] Evening Star, “Relief of Col. Forsythe” (Washington, D. C., 5 Jan 1891), 3.

[16] DeMontravel, Lieutenant General Nelson A. Miles, 360–361.

[17] RIBKWC, 655.

[18] George W. Cullum, Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U. S. Military Academy, vol. 2, (New York: James Miller, Publisher, 1879), 539-540, and 800-802.

[19] Military Times, “Valor Awards for Frank Dwight Baldwin,” Military Times Hall of Valor (https://valor.militarytimes.com/hero/907) accessed 27 Jul 2014; Robert H. Steinbach, “BALDWIN, FRANCIS LEONARD DWIGHT,” Handbook of Texas Online (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fba43), accessed 27 Jul 2014, uploaded on 12 Jun 2010; Adjutant General’s Office, “Baldwin, Frank D.,” Letters Received, compiled 1871 – 1894, documenting the period 1850 – 1917, File Number: 3365 ACP 1875, image: 791 (http://www.fold3.com/image/1/303446614/) accessed 28 Jul 2014. This file on Frank D. Baldwin contains the following regarding his brevet promotions: “Frank D. Baldwin, now captain 5th Infantry, when recommended was 1st Lieut. 5th Infantry. Recommended for gallantry at Red River, Indian Territory, August 30, 1874, by Major General N. A. Miles, May 26, 1890, (late commanding Indian Territory Expedition) and by the same officer at the same time for gallant and successful attack on Sitting Bull’s Camp on Big Dry River, Montana, December 18, 1876. Also recommended for distinguished services in a fight with hostile Indians, on Salt Fork of Red River, Texas, November 8, 1874, to date from September 7, 1874, and for distinguished services in an engagement on McClellan’s Creek, Texas, November 8, 1874, resulting in the complete routing of a large body of Indians, and the re-capture of two white girls held captive by them, to date from November 8, 1874, by Colonel N. A. Miles, 5th Infantry, commanding Indian Territory Expedition, and General Pope, Sheridan, March 11, 1873. Also recommended for conspicuous gallantry in leading his command in a successful charge against a superior number of hostile Indians, strongly posted, at the battle of Wolf Mountain, Montana, January 8, 1877, to date January 8, 1877, by Colonel N. A. Miles, 5th Infantry, commanding District of the Yellowstone, and Generals Terry, Sheridan and Sherman, February 9, 1877. June 25, 1890, General Schofield will recommend two brevets for the whole of foregoing.”

[20]] George E. Trager, photo., “Gen. Miles & staff during late Indian War at Pine Ridge Agcy,” Northwest Photographic Co., Denver Public Library Digital Collection (http://cdm15330.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15330coll22/id/24030) accessed 27 Jul 2014.

[21] Russell, “Selfless Service,” 145; University of Washington, “James W. Forsyth Family Papers,” (Seattle: University Libraries, 2011); Peter R. DeMontravel, A Hereo to His Fighting Men: Nelson A. Miles, 1839-1925, (Kent: The Kent State University Press, 1998), 206.

[22] National Archives “Sioux Campaign, 1890-91,” 813-814 (letter from Miles to Schofield dated 5 Jan 1891).

Citation for this article: Samuel L. Russell, “Wounded Knee Investigation” Army at Wounded Knee (Sumter, SC: Russell Martial Research, 2013-2015, http://wp.me/P3NoJy-vD), updated on 27 September 2015, accessed date __________.

Dear sir My name is Janet Snavely I’m looking for info on myGreat Grandfather Archie Bruch this is the info I do know , Troop D regiment 7th Calvary Fort Riley Kansas it was told that he was in Wounded Knee . If you could contact me with information on him it would be greatly excepted

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ms. Snavely… I have your relative listed on the D Troop muster roll. Following is the entry for Private Burch:

Private Burch, Archie: Enlisted on April 29, 1890 at Concordia, Kansas, by Lieut. Donaldson. Sick in quarters from Dec. 23, 90 to Dec. 25, 90. Disease “acute bronchial catarrh” contracted in line of duty.

There is quite a bit of information about Archie Burch on Ancestry.com including this photograph.

LikeLike

There has been a granite monument erected 2014 in Niagara Falls NY. to 1st Sgt. Fredrick Toy who participated in the so called battle at Wounded Knee. A meeting took place Wednesday the 14th of January 2015 between myself, a Niagara Falls reporter and a representative of the Seneca Nation. There is controversy and concerns over this monument and the history and meaning behind it. Was 1st Sgt. Fredrick Toy deserving of this medal along with the other 19 Troopers? An article in the Niagara Falls Gazette will follow after the 14th of January interview. Tom Poor Bear Vice president of the Oglala Nation is also aware of this monument, and is hoping this monument in the future will be removed. In 2001 The National Congress Of American Indians passed two resolutions to have these medals rescinded to no avail.

LikeLike

Sir… Thank you for the comment on my blog post concerning Sergeant Frederick Ernest Toy and the monument erected in his honor in Niagara Falls, NY. I was unaware of the monument and am very interested in it and the forth coming article that you mentioned. I would appreciate greatly any additional information concerning both that you care to provide.

You asked specifically if Sgt. Toy was deserving of his medal. The short answer is, yes. Understand that the Medal of Honor as awarded in 1891, is not the same as the Medal of Honor that we know of and understand today. I address this change in the Medal of Honor criteria as set forth by Congress and implemented by the War Department in my post, Gallantry in Action.

Sergt. Toy met that criteria in 1891 when his commander, Capt. Winfield Scott Edgerly, recommended him. The recommendation in accordance with standards of that time was endorsed through the regiment’s commander, Col. James W. Forsyth, through the Department Commander, Brig. Gen. Wesley Merritt, and through the Commanding General of the Army, Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield, before being approved by the Assistant Secretary of War, Lewis A. Grant, all of which was the established process for that era. Moreover, Sgt. Toy’s Medal of Honor was one of thousands that were reviewed in 1916 and 1917 by a Congressional review process to determine if previous recipients were deserving of their medals. This board was headed by Lieutenant General (retired) Nelson A. Miles, who was the most outspoken military or government critic of Colonel Forsyth’s and the Seventh Cavalry’s performance at Wounded Knee. Following are the notes from that board concerning the review of Sergt. Toy’s medal.

[1] United States Congress, 66th Congress, 1st Session, May 19 – November 19, 1919, Senate Documents, Volume 14, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1919), 410.

One cannot look at or pass judgement 125 years removed from an event, on a specific Medal of Honor, or group of Medals of Honor, without considering the context in which medals were awarded during that era. Looked at holistically, the medals awarded to troopers and artillerymen during the Pine Ridge Campaign of November 1890 to January 1891, pass the same muster as all other medals awarded during the Indian Wars period. To revoke any one of them, would, in my opinion, necessitate revoking all. Moreover, the trite and misinformed opinion that more medals were presented for Wounded Knee than any other single day’s action is patently false as I point out in my previously referred to post on the subject. Following is what I have written on that topic when reviewing a book that made that claim.

I believe Sergeant Toy’s descendants and his community at large are justified in their pride of Sergeant Toy’s actions while serving his nation in the 7th U.S. Cavalry. Not only was his medal deserving, the monument erected in his honor is a fitting, and what I hope will be a lasting, tribute to this heroic American soldier.

Colonel Sam Russell, U.S. ArmySergeant Frederick Ernest Toy

LikeLike

My husband Edward Feigenbaum II is the great-grandson of Sgt. Frederick Toy. We inherited Frederick’s Medal of Honor and display it with honor in our home. We are all proud of the valor Sgt. Toy showed during the war, and his legacy will always be revered. My father-in-law Edward P. Feigenbaum I, also carried on the military legacy, serving in the Army during World War II and was a POW. And lastly, my husband Ed followed in the steps of these great men, serving in the active Army for 20 years and is an Iraq war veteran. Your blog and your research Col. Russell is amazing! Thank you for your service!

LikeLike

Thank you for your heartfelt comment. Do you have a picture of Frederick Toy’s Medal of Honor that you can share?

LikeLike

Yes I do! I have it in my formal living room! How can I send you a picture?

LikeLike

Please send it to v8m8i@aol.com. A picture of the engraving on the back of the medal would be greatly appreciated.

LikeLike

Andrew white is buried in woodside cemetery paisley scotland.

The rumors where he served at the battle of little big horn, when he returned to paisley where on well street he was killed by horse and cart..

Photo:

https://plus.google.com/u/0/b/105450673022006301003/105450673022006301003/posts/ErWNFUekmNt

You have my permission to use the photo in the link above…

LikeLike

Mr. Cameron… Thank you for the post. According to his headstone, Andrew White was born in 1860 making it highly unlikely that he fought at the Little Bighorn in 1876. Sergeant Andrew White was at Wounded Knee assigned to Captain Moylan’s A Troop. He first enlisted on 17 July 1882 at St. Louis, Mo. He listed his age as 22 years and 4 months, born in Paisley, Scotland, a bookkeeper with blue eyes, sandy hair, and a fair complexion, standing five feet six and a half inches. He retired on 18 June 1907 after twenty-five years service. As inscribed on his grave marker, he retired as a Regimental Quartermaster Sergeant of the 7th Cavalry.

LikeLike

Thanks for that info, it all adds to the myth and Woodside’s history..

By the way and off topic, Ronald Reagan visited Paisley in the early 90s when he was president, where at Castlehead cemetery he laid flowers to relatives buried their. We’ve had on going issues with the church being sold off and the new owners wanting to remove grave stones. Though they plane to leave the graves, where they’d like to turn this historic and our cultural ties with the US into a car park of all things. Shocking to say the least.

Woodside & Castlehead church are a stones throw away, much like the statues to John Witherspoon who signed your declaration of independence thus strengthening paisley & the US ties that should never be broken or desecrated for the sake of tarmac… His statue stands outside the university west of SWcotland

Thanks Sam,

you have great weekend and greater life ;))

LikeLike

Updated 7 Sep 2015: On a recent trip to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania I was able to obtain copies of Brigadier General Brooke’s correspondence from the Sioux Campaign of 1890-91. I discovered the 30 December telegram exchange between Generals Miles and Brookes regarding the failure to report timely and accurate troop casualties at Wounded Knee. I have updated this post based on those telegrams.

LikeLike

Dear Mr. Russell:

I have been an historian for almost five decades now. I must say I find your work very authoritative, complete, and objective. Well Done Sir.

Recently, I have been researching the various Native American – U.S. conflicts, including Wounded Knee. In delving into the details of the incident, I have come across two accounts mentioning the four Hotchkiss guns supporting the cavalry. In one, they are referred to as machine guns and both state they were firing at a combined rate of 55 rounds per minute and 1 round per second respectively.

However, that contention seems highly unlikely, as further examination showed the guns were single shot breech loading 1.65 inch cannons. Especially when the facts they lacked recoil mechanisms and would have had to be re-positioned after every shot; and would quickly overheat at that rate of fire are taken in to account.

Neither of the above mentioned narratives cites a source for this information. Do you know of any report by members of the artillery unit that could clarify this issue or where the figure of one round a second came from? Any information would be greatly appreciated.

LikeLike

Mr. Hitchcock… Thank you for your comment. I addressed this very issue last year in a letter I wrote to Congress addressing proposed resolution to rescind Medals of Honor https://armyatwoundedknee.com/2019/08/02/setting-the-record-straight-regarding-h-r-3467-remove-the-stain-act/. Below is that section of my letter and my source citation.

House Resolution 3467 Remove the Stain Act. Section 2 Findings, paragraph (8) This engagement became known as the “Wounded Knee Massacre”, and took place between unarmed Native Americans and soldiers, heavily armed with standard issue army rifles as well as four “Hotchkiss guns” with five 37 mm barrels capable of firing 43 rounds per minute.

For the record, this Act incorrectly describes the Hotchkiss gun as having five revolving 37mm barrels. There was a Hotchkiss Revolving Cannon matching that description but not at Wounded Knee. The Hotchkiss mountain howitzers employed at the fights at Wounded Knee and White Clay creeks were 1.65-inch caliber (42mm) with a single barrel. While rates of fire for this gun is difficult to ascertain, one artillery expert estimated it at 12 to 24 rounds a minute per battery (six guns), which would equate to 2 to 4 rounds per gun. There were four Hotchkiss guns at Wounded Knee. There is no historical evidence available to accurately estimate how many rounds were fired at Wounded Knee, much less any gun’s rate of fire. It certainly was not 43 rounds per minute even across the whole battery, as deceptively described in the Act. [Source: Larry D. Roberts, “Battery E, 1st Artillery at Wounded Knee – December, 1890,” South Dakota State University, 6.]

LikeLike

Sir, your work has been instrumental in helping me work on an Article for the Army Lawyer. I am working on the Killing of Lt. Casey at the moment but in the future am probably going to do an in-depth analysis of whether or not Wounded Knee was a “war crime,” as it was known then and now. If you want to collaborate let me know!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Always glad to collaborate on anything related to the Army’s actions at Wounded Knee. Reach me at v8m8i @ aol.com

LikeLike