There were four or five Indians lying on the ground with their blankets on, supposedly dead. But suddenly a shot was fired and we saw a man drop.

Andrew Mitchell Flynn was a twenty-five-year-old Scottish emigrant and a private in Captain Myles Moylan’s A Troop at Wounded Knee; he filled the role of a medic during the battle. Almost five decades after that fateful day, Flynn provided his reminiscences, which were published originally in the November-December 1939 edition of Winners of the West. Flynn’s account is a fascinating look at the earliest advent of soldiers as combat medics. Following is a portion of his account of the fights along the Wounded Knee and White Clay Creeks.

….By this time, I was getting very well acquainted with the place [Fort Riley] and the people there. I used to go to chapel on Sundays and take part in the services and I became acquainted with Major Van R. Hoff. As they had no children, they invited me to their home and were very nice to me.

About this time, our head sergeant surgeon asked me if I would like to learn first aid to the injured. I told him I would like to very much and he gave me all the instructions. I learned it very thoroughly, passing two examinations in it. Then I asked for a transfer to the hospital detachment but was refused. I asked my captain, Myles Moylan, who had always been very nice to me, why I had been refused. He told me that he wanted me with him as a “non-com.” I told him that I thought that I was too young for that, but he said that I would do all right. About that time there were rumors of the Indians going on the warpath and I said to my captain, “If you were wounded, would you want someone who did not know how take care of you, or would you rather have me?” He just laughed it off.

This 1890 photograph titled, “Pine Ridge Agency, S.D. (field maneuvers)” depicts soldiers of the hospital corps at the Pine Ridge Agency practicing their craft. (From the Louise Stegner collection held in the Denver Public Library Digital Collections)

Well, we did get into that war. In the latter part of September, 1890, we had word to pack up and go to Pine Ridge, South Dakota. We traveled over the F. E. and M. V. [Fremont-Elkhorn & Missouri Valley] Railroad and detrained at a junction point named Rushville in Nebraska, which we left as soon as possible for Pine Ridge, where we pitched our tents in a little valley. There were some negro troops there who gave us food.

We were encamped there until the 27th of December, when we were ordered out to Wounded Knee to intercept Chief Big Foot and his tribe of renegade Indians. We had only four troops with us, but we went after the enemy and captured them without a fight and brought them into camp at Wounded Knee. This was on the afternoon of the 28th December. Half of A and I Troops had charge of guarding the Indians, so we put a chain guard around them and had them pretty well tied up, we thought, though we were not as confident as we might have been because we had a feeling that they had some guns with them. We discovered later that they did, but it turned out that the guns were their undoing because they did not know how to reload them. We were very glad when about eight o’clock we saw the four troops coming on the other side. That evening as I was lying down with a piece of a bale of hay for my pillow and the stars for my canopy, there was a great commotion among the Indians which lasted most of the night. We discovered that it was the old medicine man chanting over a death.

One of our scouts asked me if I knew what he was saying. I replied that I did not. He then said to me, “Have you said your prayers yet?,” and I said “yes.” [The scout replied] “The medicine man is telling the Indians not to give up their guns because they were to be killed anyway.”

We were formed in a hollow square which was a bad thing for us because it took our men so long to get out of each other’s way when the firing started. That was how so many of our men were killed or wounded before we had a chance to use our guns.

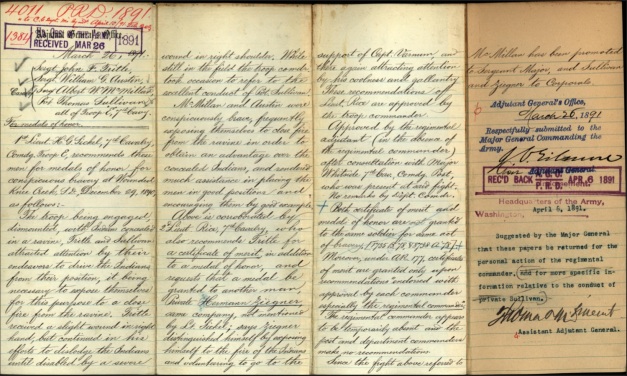

As I had charge of a squad of first aid men, I handled the bandages and other medical supplies and was quite busy. I may say here that the first man we picked up was our first lieutenant, Ernest A. Garlington, of Troop A. He had a compound fracture of the right elbow. I first stopped the flow of blood, although he had lost quite a lot of it. I took my lance and ripped the sleeve from his blouse. But before I had it all done, he said, “Hell! That’s my new blouse!” I cut not only the sleeve of his blouse, but his shirt sleeve, too, and stopped the flow of blood, and then took him to his tent and laid him on his bed.

Then he fainted and I had quite a time with him, but had a little medicine on my hip and found a silver teaspoon and put some of the “medicine” in it and worked till I got some of it into his mouth and he opened his eyes and said, “The red devils got me!” He wanted to get his pistol, but I told him he did not need it and if he did have it he could not use it. I then went down to the hospital tent and told the surgeon, Major John Van R. Hoff, about Lieutenant Garlington, telling him that I had done the best I could for him and I was hurrying out to look for some more of the wounded, when he told me to sit down and rest. I told him I could not stop and he said that there were a lot more of the men out there who could handle the rest of the wounded. He then went to his medicine chest and brought me something in a little glass. I told him that I did not drink, but he said he knew but that this was medicine and he held up a small mirror to my face. It was as white as a sheet. Then he gave me some more. It did seem to help some.

On my going out on the field again, I met Second Lieutenant John C. Waterman. There were four or five Indians lying on the ground with their blankets on, supposedly dead. But suddenly a shot was fired and we saw a man drop. Lieutenant Waterman and I went around the corner of a tent near the Indians and watched them. We saw one of them raise his head a little and as he saw someone coming toward him, fired on him. Lieutenant Waterman sent for the sharpshooter crew and they came on the double quick and each of them got this man. As I was walking towards the ravine where there was still some shooting going on, I met Second Lieutenant Thomas Q. Donaldson, Jr.* He had been shot in the groin. He had his watch in his little pocket of his pants and it was all smashed.

* Lieutenant Donaldson was not wounded in the battle. Flynn certainly treated Second Lieutenant Harry L. Hawthorne, 2nd Artillery, who was wounded in just such a manner.

I picked out the broken glass and other stuff and cleaned the wound with medicated gauze and sent him to the hospital. While doing this, we were crouching behind an old wagon. A bullet hit him on the rim of the wheel quite close and we hurried to better cover as there were quite a few Indians in that part of the ravine, which overhung, giving a shelter from the outside. The bravest deed that was done to my knowledge was that of a corporal from the artillery.* He ran his little Hotchkiss gun right up to the mouth of the ravine and stayed there until he had gotten the last man there. In looking over his gun after the battle, the marks of the Indians’ bullets were right over the muzzle of his gun.

* This was Corporal Paul H. Weinert, E Battery, 1st Artillery, who was awarded the Medal of Honor for this feat.

There have been various stories told by others and these have been taken from reports. I was there on the job from the beginning to the end–first in the capture of Big Foot and then in the bloody fight. Our men did not have much chance to get at the Indians as we were formed in a hollow square and it took some time to get in position to use our guns and they did good work then, but the Indians were better armed than we were. The old medicine man had about sixteen bullet holes in his body. The first shot was fired by some crazy Indian. The one mistake that I saw was that the Indians should have been made to remove their blankets, for after the first shots were fired, before inspection, there were four or five big bucks who dropped down on their faces as though they were dead and as I was passing near them there was a man a few yards from where I was standing who was shot through the calves of both legs. Some of the first aid men picked him up.

I met Lieutenant Waterman and he asked if I knew where the shots had come from. I told him that I was going to find out. So I went behind one of our tents and hid and by and by there was a man going across from where we stood and one of the supposed-to-be-dead Indians lifted his head and fired at this man. Fortunately, he missed. I told the lieutenant that he should call the firing squad, which he did in a hurry. When they opened fire on these men, they let out a great yell and threw their blankets and guns away. But it was no good. They were all killed. It was shortly after that that I had saved Lieutenant Garlington’s life. He was very severely wounded. He had suffered a compound fracture of the right elbow. I know that I saved his life and Surgeon Major John Van R. Hoff will bear me out in my statement, as I reported to him about Lieutenant Garlington. He was our lieutenant of A Troop. I did not see my captain, Myles Moylan, during the fight, but he was on the job like all the other good soldiers.

As I went up and down the camp to see the wounded and give them a drink of water and speak words of comfort to them, a man called me over to where he was laying in the hospital then and told me he had some kind of weight on his back. I examined him and found that a bullet had lodged between his flesh and his skin and I just took my little lance and cut a little hole there and took out the bullet and gave it to him as a keepsake. When I fixed him up he felt much more comfortable. I believe this man was Sergeant George Lloyd of Troop I. There were many others whom I helped, also, but the shooting finally ended and I was very glad to get to our troop again. That was a trying time.

As we did not have much room, we had to load up the dead and put the wounded on top of them. Just as I was looking over the field, I came across a dead squaw and a little papoose who was sucking on a piece of hardtack. I picked up the little papoose and carried it in my arms. A little way farther on, I found another dead squaw and another papoose. I picked it up, too, and brought them over near the hospital tent, where there were a number of Indian women.

As I came over to where they were, I met a big, husky sergeant who said, “Why didn’t you smash them up against a tree and kill them? Some day they’ll be fighting us.”

I told him I would rather smash him than those little innocent children. The Indian women were so glad that I saved the papooses that they almost kissed me. But I told them I didn’t have time for that.

I also found a white woman who was shot in the wrist. I asked here how she came to be there and she said that she had been stolen from her people. On going a little way farther, we passed on old outhouse and we heard a noise inside, somewhat like a cat, and we looked in and saw a little papoose. She was a beautiful child and clothed in a fine buckskin suit. Second Lieutenant Herbert G. Squires* went in and got it and it began to laugh so he said it’s name would be Laughing Swan, and that he was going to take it home to his wife, which he did. After everything was loaded up, we saddled our horses and prepared to march to Pine Ridge and on getting outside of Wounded Knee we saw that the prairie ahead of us had been set on fire. We had to detour for quite a way before we got on the road to Pine Ridge. Then we met a troop of horsemen. We did not know whether they were friend or foe, so they called out to us to find out who we were and we did the same. We found that they were coming out to help us so we finally got to Pine Ridge, where the wounded were taken care of.

* Lieutenant Herbert G. Squiers was not present at the battle of Wounded Knee, having returned to Fort Riley a few days earlier to appear before a board of promotion. Flynn may have confused him with another officer, although I have found no historical evidence that any officer present at the battle adopted a Lakota infant. The most famous abduction and subsequent adoption of an infant survivor of Wounded Knee was General Colby of Nebraska National Guard and his Lakota daughter, Lost Bird. Colby was not at Wounded Knee.

On the following day, December 30, six troops of the Seventh Cavalry were ordered out to White Clay Creek or Mountain. Some claim this was almost another Custer field, as shots were fired at us from all directions as we left our horses in a sheltered place and crawled up the side of the mountain. Major Whitside had to call for a volunteer to go into Pine Ridge and get out the ninth Cavalry (colored), commanded by Colonel Guy V. Henry.

The volunteer came up to Major Whitside and saluted him and said: “Well, Major, I got to go sometime once, so I will go.”

He had a fine horse and then Major Whitside took him by the hand and shook it heartily and said, “God be with you!” and away he went in flying charge you ought to have seen the bullets fly. He got away safely and reached General Miles* at Pine Ridge. His horse dropped dead and he lay down by the dead horse and cried as though his heart would break.

* General Miles was at Rapid City on 30 December. The trooper likely reported to Brigadier General John R. Brooke.

General Miles said to him, “I will get a new horse.”

But he said, “Oh, General, there is no more like him. We were great pals.”

The reason for sending for reinforcements was that the Indians were coming from all sides. You could take your hat and put it on your gun, and, Bang! The bullets came flying. Major Whitside called for the sharpshooters to get their guns loaded. Then someone put his hat on his gun, so that they could see where the shots would come from. As soon as they found out, they fired two volleys and there were no more shots from the Indians.

In the meantime, Colonel Guy V. Henry’s Black Demons came up the side of the mountain yelling and shooting. They came in the shape of a V. Out of this victory we had seven wounded and one killed. First Lieutenant James D. Mann was wounded and died when he reached Fort Riley. We lost two very fine officers–George D. Wallace, who was killed [at Wounded Knee] by an Indian war club by a squaw; his skull being partly lifted off his head, but there were six dead Indians at this feet and he still had his gun.

We got down from the side of the mountain and got our field guns across on the other side and fired a volley out of them. It went into the Indian powwow that was being held. We shelled it and broke it all up. There were a large number of Indians seemingly on the warpath and there were strict orders sent to the several chiefs to turn all guns over to the government. There were a few weeks spent in getting the guns and sending the men back to where they belonged, as they had buried a lot of the guns in pits. Then the Indians went into a place which looked like an amphitheater. When they went in they had some cattle and when they had eaten them all up they wanted to get out and get some more.

Some of the chiefs wanted to have a powwow with some of the generals and told them they would not give in their guns or men. General Miles told them to tell the Indians that they had to give up their guns. In the meantime, the artillerymen during the night had put up the field guns and put a tent over them. They were standing on the side of a hill and the Indians did not know what was in the tent. It was almost directly across from where the Indians were camped and during the powwow General Miles and his staff told the chiefs to come with them and they went right up to the tent and were told that every gun they had in the camp where they were and those guns that they had buried must be given up. They said, “No give up the guns! No go back to reservation.”

At a given signal, the tent was opened up and the two guns were pointed right at the place where the Indians were camped. They grunted, then they saw the guns. They were told, “Now, you give up the guns and send the Indians back to the reservation or there will be no Indians left.” There were two chiefs whose names I remember, …Rain in the Face and Young Man Afraid of His Horses, who, by the way, was made a chief of all the scouts. So the chiefs were told that there would be wagons placed near them and every man was to give his gun to be put in the wagons. Then Young Man Afraid of His Horse’s (which was a misnomer, for he was not afraid of anything) told them to get busy and the first Indian that wanted to go and fight would be shot and I will be the shooter, he said. They gave up their guns and started back to their tepees and it took quite a few days before this was done. There were some scouts sent out around to see if they could dig up any more guns.

I shall never forget that last day when they buried the dead soldiers. They could not fire a volley over the graves for fear of arousing the Indians. All they could do was to blow taps. It was a terribly dreary day–the sky seemed to bend down to earth. Of course, I was just a young chap then and had not seen anything like this before. There were lots of the older soldiers who had never seen it either. We broke up camp from Pine Ridge and camped away towards Nebraska. It seemed the whole United States Army was there. The tents seemed to stretch away about five miles, and you could see the Indians peeking over the tops of the mountains. I had quite a few talks with Old American Indian Horse. He said that the man that started the ghost dances was a fanatic. Someone was saying that he must have heard the missionaries talking about it. But why blame the missionaries? They had not told this man about the Indians and buffaloes coming back at that time. The missionaries did a great deal of good all over the western country.

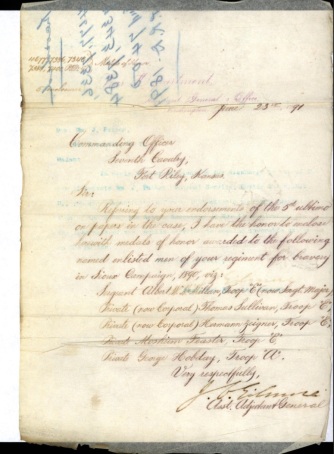

In closing this narrative of forty-nine years ago, I should like to say that I believe that I have given a true story. An article in which appears a list of eighteen men upon whom Congress has seen fit to bestow the nation’s highest award, the Congressional Medal for their conduct at Wounded Knee. I should like to know just what those men did at the Battle of Wounded Knee. I myself had charge of a crew of first aid to the injured and was on the field all day taking care of the wounded. I saved Lieutenant Garlington’s life, as he had a compound fracture of the right elbow. I administered first aid to Lieutenant Donaldson. I removed a bullet from Sergeant Lloyd’s back, and helped many others. To cap the climax, I saved two papooses from someone who would doubtless have killed them and gave them to the squaws, who said “Pale Face heap good.”

I believe that I, too, was entitled to a medal for what I did. Of course, I was just a young lad and a rookie, but I did my share of good….

Source: Andrew M. Flynn, “An Army Medic at Wounded Knee,” in Indian War Veterans: Memories of Army Life and Campaigns in the West, 1864-1898, comp. Jerome A. Greene (New York: Savas Beatie, 2007), 186-192.

Citation for this article: Samuel L. Russell, “Reminiscences of Private Andrew Mitchell Flynn, A Troop Medic, 7th Cavalry,” Army at Wounded Knee (Sumter, SC: Russell Martial Research, 2013-2015, http://wp.me/p3NoJy-qq), posted 11 Dec 2014, accessed date __________.

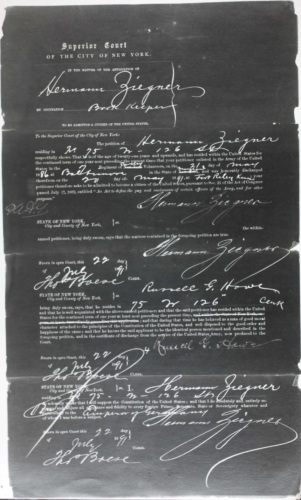

![Sergeant Ziegner's death was run in several New York Newspapers.[12]](https://armyatwoundedknee.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/sergt-ziegners-death.jpg?w=300&h=174)