The Major General Commanding takes pleasure in publishing… the names of the following… men who, during… the recent campaign in South Dakota, distinguished themselves by “specially meritorious acts or conduct in service.”

The Pine Ridge Campaign of November 1890 to January 1891 became one of the more controversial military ventures in the annals of the U.S. Army, not just due to the number of non-combatants killed at Wounded Knee, but also for the number of Medals of Honor bestowed on its participants. Eventually thirty soldiers received the Nation’s highest military decoration for their actions in South Dakota in the winter of 1890 and 1891, five received the president’s Certificate of Merit and another thirty soldiers received honorable mention from the Commanding General of the Army, although many of those men were not at the battle of Wounded Knee.

Not long after the dead were buried–Indian and soldier alike–and the wounded were in the care of medical professionals, the commanders of the units that had fought along the Wounded Knee Creek, White Clay Creek and White River began recognizing their soldiers for their conduct during the campaign. In 1891, there were only four options available to commanders to recognize soldiers for courage, bravery, or meritorious service: Honorable Mention through published General Orders, Certificates of Merit for enlisted soldiers, Brevet Promotions for officers, or Medals of Honor. Thresholds for each were ambiguous and discretion was left largely to regimental and department commanders. The War Department and Congress had not yet created lesser combat awards such as the Distinguished Service Cross, Silver Star, or Bronze Star for Valor; the first of those awards would come three decades later in 1918. The requisites for a Medal of Honor in the 1890s had remained largely unchanged since being established by Congress in 1862: soldiers who “distinguish themselves by their gallantry in action, and other soldier-like qualities.”[1] The War Department’s first attempt to more clearly define the criteria of actions that merited a Medal of Honor came in June, 1897, when Secretary Alger provided written instructions detailing the recommending and awarding of the Medal of Honor. His instructions were issued to the Army on June 30, 1897, in General Order No. 42.

…in order that the Congressional Medal of Honor may be deserved, service must have been performed in action as such conspicuous character to clearly distinguish the man for gallantry and intrepidity above his comrades–service that involved extreme jeopardy of life or the performance of extraordinary hazardous duty. Recommendations for the decoration will be judged by this standard of extraordinary merit, and incontestible proof of performance of the service will be exacted.[2]

Such a high standard for the Medal of Honor did not exist in 1891, which accounts for why so many were awarded following the Pine Ridge Campaign. Nor was that high a number of medals unusual for such action during the period called the Indian Wars. Fourteen years earlier twenty-four Medals of Honor were earned by 7th Cavalry soldiers for their actions on Reno Hill on June 25 and 26, 1876, at the Little Big Horn, all but two awarded in 1878. Moreover, thirty-one soldiers were recognized for their actions in October, 1876, at the Battle of Cedar Creek, Montana, receiving their medals six months after the engagement. In all, eighty-one medals were awarded for the Little Big Horn Campaign of 1876-1877, known by historians as the Great Sioux War. Thirty-one soldiers from the 1st and 8th Cavalry Regiments were decorated on February 14, 1870, for their actions against Cochise and his Apache warriors in a stronghold in the Chiricahua Mountains four months earlier. Those were in addition to the thirty-four medals bestowed on 8th Cavalry troopers for actions in Arizona in August, 1868, a period in the Army’s history that is not even recognized with a campaign streamer.[3]

At the conclusion of the Pine Ridge Campaign in 1891 regimental commanders submitted recommendations for all of the methods available to them. In addition to the thirty Medals of Honor, over sixty soldiers and officers were commended in General Orders, and five soldiers received Certificates of Merit. However, no officers were awarded brevet promotions, although several were recommended.

The first two soldiers were issued medals less than five weeks after the action for which they were recognized. On February 4, 1891, First Sergeant Cornelius Smith and Sergeant Fred Myers of K Company, 6th Cavalry, were decorated for repelling a superior force along the White River on January 1. By the end of March, 1891, three more Soldiers received their medals, each for action at Wounded Knee on December 29. Within a year of the close of the campaign President Benjamin Harrison bestowed medals on twenty-six soldiers. Congress recognized the gallantry of four more 7th Cavalry officers during the next five years.[4]

Of the thirty medals, seventeen were specifically for actions at Wounded Knee and one was for actions at both Wounded Knee and White Clay Creek, making it eighteen Medals of Honor awarded to soldiers for actions directly attributable to Wounded Knee. Three soldiers were recognized for actions solely at White Clay Creek. Three more troopers were decorated for their service throughout the campaign, including two from the 7th Cavalry and a Buffalo Soldier from the 9th Cavalry. The other six medals were presented to troopers from the 6th Cavalry for actions along the White River. In all, nineteen 7th cavalrymen and four Light Battery E artillerymen that fought at Wounded Knee were decorated. Following are the citations of the thirty Medals of Honor listed in the order in which they were issued.[5]

The President of the United States of America, in the name of Congress, takes pleasure in presenting the Medal of Honor to…

…First Sergeant Cornelius Cole Smith, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 1 January 1891, while serving with Company K, 6th U.S. Cavalry, in action at White River, South Dakota. With four men of his troop, First Sergeant Smith drove off a superior force of the enemy and held his position against their repeated efforts to recapture it, and subsequently pursued them a great distance. Awarded 4 February 1891.

…First Sergeant Cornelius Cole Smith, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 1 January 1891, while serving with Company K, 6th U.S. Cavalry, in action at White River, South Dakota. With four men of his troop, First Sergeant Smith drove off a superior force of the enemy and held his position against their repeated efforts to recapture it, and subsequently pursued them a great distance. Awarded 4 February 1891.

…Sergeant Frederick William Myers, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 1 January 1891, while serving with Company K, 6th U.S. Cavalry, in action at White River, South Dakota. With five men Sergeant Myers repelled a superior force of the enemy and held his position against their repeated efforts to recapture it. Awarded 4 February 1891.

…Sergeant Frederick William Myers, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 1 January 1891, while serving with Company K, 6th U.S. Cavalry, in action at White River, South Dakota. With five men Sergeant Myers repelled a superior force of the enemy and held his position against their repeated efforts to recapture it. Awarded 4 February 1891.

…Corporal Paul H. Weinert, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 29 December 1890, while serving with Battery E, 1st U.S. Artillery, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Taking the place of his commanding officer who had fallen severely wounded, Corporal Weinert gallantly served his piece, after each fire advancing it to a better position. Awarded 24 March 1891.

…Corporal Paul H. Weinert, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 29 December 1890, while serving with Battery E, 1st U.S. Artillery, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Taking the place of his commanding officer who had fallen severely wounded, Corporal Weinert gallantly served his piece, after each fire advancing it to a better position. Awarded 24 March 1891.

…Private Joshua B. Hartzog, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 29 December 1890, while serving with Company E, 1st U.S. Artillery, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Private Hartzog went to the rescue of the commanding officer who had fallen severely wounded, picked him up, and carried him out of range of the hostile guns. Awarded 24 March 1891.

…Private Joshua B. Hartzog, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 29 December 1890, while serving with Company E, 1st U.S. Artillery, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Private Hartzog went to the rescue of the commanding officer who had fallen severely wounded, picked him up, and carried him out of range of the hostile guns. Awarded 24 March 1891.

…First Sergeant Jacob Trautman, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 29 December 1890, while serving with Company I, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. First Sergeant Trautman killed a hostile Indian at close quarters, and, although entitled to retirement from service, remained to the close of the campaign. Awarded 27 March 1891.

…First Sergeant Jacob Trautman, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 29 December 1890, while serving with Company I, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. First Sergeant Trautman killed a hostile Indian at close quarters, and, although entitled to retirement from service, remained to the close of the campaign. Awarded 27 March 1891.

…Farrier Richard J. Nolan, United States Army, for bravery in action on 30 December 1890, while serving with Company I, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at White Clay Creek, South Dakota. Awarded 1 April 1891.

…Farrier Richard J. Nolan, United States Army, for bravery in action on 30 December 1890, while serving with Company I, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at White Clay Creek, South Dakota. Awarded 1 April 1891.

…First Sergeant Theodore Ragnar, United States Army, for bravery on 30 December 1890, while serving with Company K, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at White Clay Creek, South Dakota. Awarded 13 April 1891.

…First Sergeant Theodore Ragnar, United States Army, for bravery on 30 December 1890, while serving with Company K, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at White Clay Creek, South Dakota. Awarded 13 April 1891.

…Sergeant George Loyd, United States Army, for bravery, especially after having been severely wounded through the lung on 29 December 1890, while serving with Company I, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Awarded 16 April 1891.

…Sergeant George Loyd, United States Army, for bravery, especially after having been severely wounded through the lung on 29 December 1890, while serving with Company I, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Awarded 16 April 1891.

…Sergeant James Henry Ward, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 29 December 1890, while serving with Company B, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Sergeant Ward continued to fight after being severely wounded. Awarded 16 April 1891.

…Sergeant James Henry Ward, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 29 December 1890, while serving with Company B, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Sergeant Ward continued to fight after being severely wounded. Awarded 16 April 1891.

…Private Marvin Charles Hillock, United States Army, for distinguished bravery on 29 December 1890, while serving with Company B, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Awarded 16 April 1891. [Hillock was recommended for actions at White Clay Creek but was erroneously cited by the War Department for Wounded Knee.]

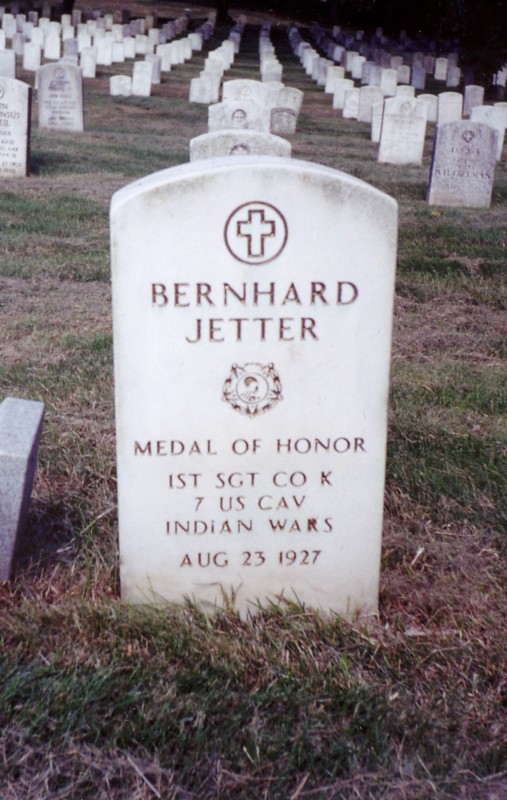

…Sergeant Bernhard Jetter, United States Army, for distinguished bravery on December, 1890, while serving with Company K, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action during the Sioux Campaign in South Dakota. Awarded 24 April 1891.

…Sergeant Bernhard Jetter, United States Army, for distinguished bravery on December, 1890, while serving with Company K, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action during the Sioux Campaign in South Dakota. Awarded 24 April 1891.

…Captain John Brown Kerr, United States Army, for distinguished bravery on 1 January 1891, while in command of his troop of the 6th U.S. Cavalry, in action against hostile Sioux Indians on the north bank of the White River, near the mouth of Little Grass Creek, South Dakota, where he defeated a force of 300 Brule Sioux warriors, and turned the Sioux tribe, which was endeavoring to enter the Bad Lands, back into the Pine Ridge Agency. Awarded 25 April 1891.

…Captain John Brown Kerr, United States Army, for distinguished bravery on 1 January 1891, while in command of his troop of the 6th U.S. Cavalry, in action against hostile Sioux Indians on the north bank of the White River, near the mouth of Little Grass Creek, South Dakota, where he defeated a force of 300 Brule Sioux warriors, and turned the Sioux tribe, which was endeavoring to enter the Bad Lands, back into the Pine Ridge Agency. Awarded 25 April 1891.

…First Lieutenant Benjamin Harrison Cheever, Jr., United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 1 January 1891, while serving with 6th U.S. Cavalry, in action at White River, South Dakota. First Lieutenant Cheever headed the advance across White River partly frozen, in a spirited movement to the effective assistance of Troop K, 6th U.S. Cavalry. Awarded 25 April 1891.

…First Lieutenant Benjamin Harrison Cheever, Jr., United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 1 January 1891, while serving with 6th U.S. Cavalry, in action at White River, South Dakota. First Lieutenant Cheever headed the advance across White River partly frozen, in a spirited movement to the effective assistance of Troop K, 6th U.S. Cavalry. Awarded 25 April 1891.

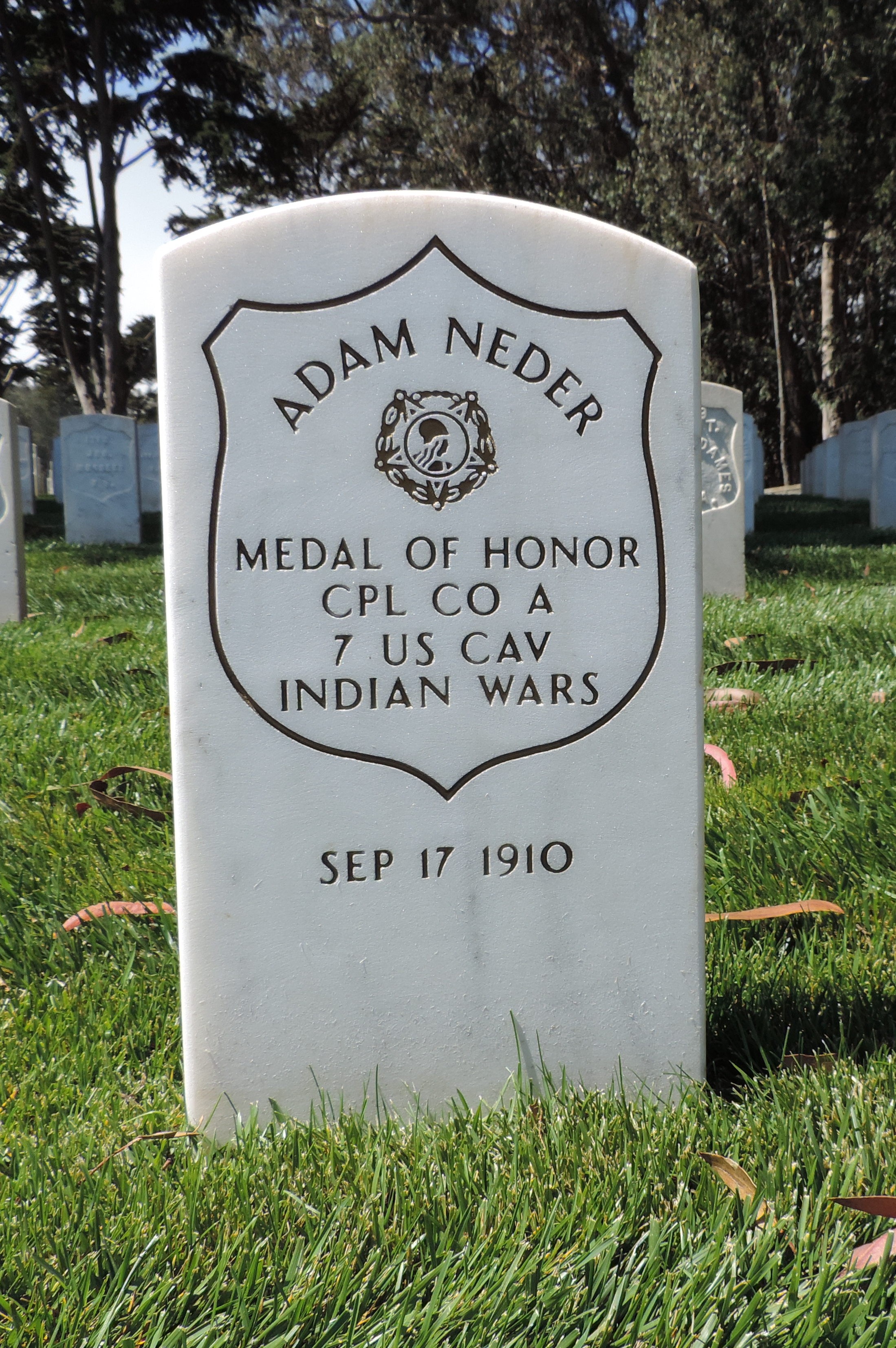

…Private Adam Neder, United States Army, for distinguished bravery on December, 1890, while serving with Company A, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action during the Sioux Campaign. Awarded 25 April 1891.

…Private Adam Neder, United States Army, for distinguished bravery on December, 1890, while serving with Company A, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action during the Sioux Campaign. Awarded 25 April 1891.

…Sergeant Joseph F. Knight, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 1 January 1891, while serving with Troop F, 6th U.S. Cavalry, in action at White River, South Dakota. Sergeant Knight led the advance in a spirited movement to the assistance of Troop K, 6th U.S. Cavalry. Awarded 1 May 1891.

…Sergeant Joseph F. Knight, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 1 January 1891, while serving with Troop F, 6th U.S. Cavalry, in action at White River, South Dakota. Sergeant Knight led the advance in a spirited movement to the assistance of Troop K, 6th U.S. Cavalry. Awarded 1 May 1891.

…Private Mathew H. Hamilton, United States Army, for bravery in action on 29 December 1890, while serving with Company G, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Awarded 25 May 1891.

…First Sergeant Frederick Ernest Toy, United States Army, for bravery on 29 December 1890, while serving with Company G, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Awarded 26 May 1891.

…First Sergeant Frederick Ernest Toy, United States Army, for bravery on 29 December 1890, while serving with Company G, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Awarded 26 May 1891.

…Sergeant Albert Walter McMillan, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 29 December 1890, while serving with Company E, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. While engaged with Indians concealed in a ravine, Sergeant McMillan assisted the men on the skirmish line, directed their fire, encouraged them by example, and used every effort to dislodge the enemy. Awarded on 23 June 1891.

…Sergeant Albert Walter McMillan, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 29 December 1890, while serving with Company E, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. While engaged with Indians concealed in a ravine, Sergeant McMillan assisted the men on the skirmish line, directed their fire, encouraged them by example, and used every effort to dislodge the enemy. Awarded on 23 June 1891.

…Private Mosheim Feaster, United States Army, for extraordinary gallantry on 29 December 1890, while serving with Company E, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Awarded on 23 June 1891.

…Private Mosheim Feaster, United States Army, for extraordinary gallantry on 29 December 1890, while serving with Company E, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Awarded on 23 June 1891.

…Private George Hobday, United States Army, for conspicuous and gallant conduct in battle on 29 December 1890, while serving with Company A, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Awarded on 23 June 1891.

…Private George Hobday, United States Army, for conspicuous and gallant conduct in battle on 29 December 1890, while serving with Company A, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Awarded on 23 June 1891.

…Private Herman Ziegner, United States Army, for conspicuous bravery on December 29 & 30, 1890, while serving with Company E, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek and White Clay Creek, South Dakota. Awarded on 23 June 1891.

…Private Herman Ziegner, United States Army, for conspicuous bravery on December 29 & 30, 1890, while serving with Company E, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek and White Clay Creek, South Dakota. Awarded on 23 June 1891.

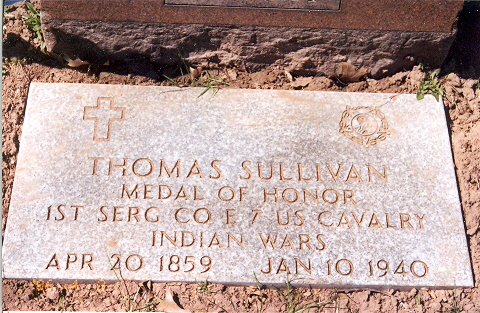

…Private Thomas Sullivan, United States Army, for conspicuous bravery in action against Indians concealed in a ravine on 29 December 1890, while serving with Company E, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Awarded 23 June 1891.

…Private Thomas Sullivan, United States Army, for conspicuous bravery in action against Indians concealed in a ravine on 29 December 1890, while serving with Company E, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Awarded 23 June 1891.

![Colonel W. G. Austin, Quartermaster Reserve Corps of the National Army.[19]](https://armyatwoundedknee.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/colonel-w-g-austin-n-a.jpg?w=118&h=229) …Sergeant William Grafton Austin, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 29 December 1890, while serving with Company E, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. While the Indians were concealed in a ravine, Sergeant Austin assisted men on the skirmish line, directing their fire, etc., and using every effort to dislodge the enemy. Awarded on 27 June 1891.

…Sergeant William Grafton Austin, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 29 December 1890, while serving with Company E, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. While the Indians were concealed in a ravine, Sergeant Austin assisted men on the skirmish line, directing their fire, etc., and using every effort to dislodge the enemy. Awarded on 27 June 1891.

…Second Lieutenant Robert Lee Howze, United States Army, for bravery in action on 1 January 1891, while serving with Company K, 6th U.S. Cavalry, in action at White River, South Dakota. Awarded on 25 July 1891.

…Second Lieutenant Robert Lee Howze, United States Army, for bravery in action on 1 January 1891, while serving with Company K, 6th U.S. Cavalry, in action at White River, South Dakota. Awarded on 25 July 1891.

…Corporal William O. Wilson, United States Army, for gallantry on 30 December 1890, while serving with Company I, 9th U.S. Cavalry, in carrying a message for assistance through country occupied by the enemy, when the wagon train under escort of Captain Loud was attacked by hostile Sioux Indians, near the Pine Ridge Agency, South Dakota.

…Corporal William O. Wilson, United States Army, for gallantry on 30 December 1890, while serving with Company I, 9th U.S. Cavalry, in carrying a message for assistance through country occupied by the enemy, when the wagon train under escort of Captain Loud was attacked by hostile Sioux Indians, near the Pine Ridge Agency, South Dakota.

…Musician John E. Clancy, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 29 December 1890, while serving with Company E, 1st U.S. Artillery, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Musician Clancy twice voluntarily rescued wounded comrades under fire of the enemy. Awarded on 23 January 1892.

…Second Lieutenant Harry Leroy Hawthorne, United States Army, for distinguished conduct in battle with hostile Indians on 29 December 1890, while serving with 2d U.S. Artillery, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Awarded on 11 October 1892.

…Second Lieutenant Harry Leroy Hawthorne, United States Army, for distinguished conduct in battle with hostile Indians on 29 December 1890, while serving with 2d U.S. Artillery, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Awarded on 11 October 1892.

…First Lieutenant Ernest Albert Garlington, United States Army, for distinguished gallantry on 29 December 1890, while serving with 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Awarded on 26 September 1893.

…First Lieutenant Ernest Albert Garlington, United States Army, for distinguished gallantry on 29 December 1890, while serving with 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. Awarded on 26 September 1893.

…First Lieutenant John Chowning Gresham, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 29 December 1890, while serving with 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. First Lieutenant Gresham voluntarily led a party into a ravine to dislodge Sioux Indians concealed therein. He was wounded during this action. Awarded on 26 March 1895.

…First Lieutenant John Chowning Gresham, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 29 December 1890, while serving with 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota. First Lieutenant Gresham voluntarily led a party into a ravine to dislodge Sioux Indians concealed therein. He was wounded during this action. Awarded on 26 March 1895.

…Captain Charles Albert Varnum, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 30 December 1890, while serving with Company B, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at White Clay Creek, South Dakota. While executing an order to withdraw, seeing that a continuance of the movement would expose another troop of his regiment to being cut off and surrounded, Captain Varnum disregarded orders to retire, placed himself in front of his men, led a charge upon the advancing Indians, regained a commanding position that had just been vacated, and thus ensured a safe withdrawal of both detachments without further loss. Awarded on 22 September 1897.

…Captain Charles Albert Varnum, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 30 December 1890, while serving with Company B, 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at White Clay Creek, South Dakota. While executing an order to withdraw, seeing that a continuance of the movement would expose another troop of his regiment to being cut off and surrounded, Captain Varnum disregarded orders to retire, placed himself in front of his men, led a charge upon the advancing Indians, regained a commanding position that had just been vacated, and thus ensured a safe withdrawal of both detachments without further loss. Awarded on 22 September 1897.

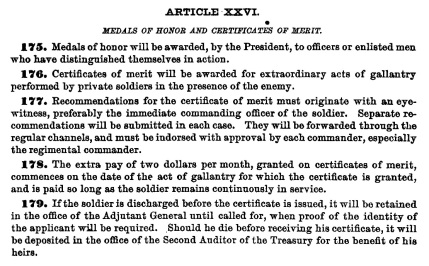

Article XXVI of the Army Regulations in 1889 provided minimal guidance on criteria for award of a medal of honor. By contrast, the specified criteria for award of the little known certificate of merit was specifically of gallantry in action.[6]

Two soldiers were later awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and one was awarded a Distinguished Service Medal. Following are the three soldiers that were decorated in later years with the newer medals.[8]

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross…

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross…

…in lieu of a previously issued Certificate of Merit and Distinguished Service Medal, to Corporal Harry W. Capron, United States Army, for extraordinary gallantry while serving as a member of Troop B, 7th Cavalry Regiment, in action at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota, 29 December 1890.

…(Posthumously) to Captain John Van Rennselaer Hoff, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism while serving as Assistant Surgeon, Medical Corps, in action against hostile Sioux Indians at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, 29 December 1890. When the Indians made a sudden treacherous attack upon the troops Captain Hoff, with utter disregard for his personal safety, attended to the dressing of the wounds of fallen soldiers.

…(Posthumously) to Captain John Van Rennselaer Hoff, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism while serving as Assistant Surgeon, Medical Corps, in action against hostile Sioux Indians at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, 29 December 1890. When the Indians made a sudden treacherous attack upon the troops Captain Hoff, with utter disregard for his personal safety, attended to the dressing of the wounds of fallen soldiers.

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Army Distinguished Service Medal to Second Lieutenant Sedgwick Rice, United States Army, for services against hostile Indians while serving with the 7th Cavalry near the Catholic Mission on White Clay Creek, South Dakota, on 30 December 1890.

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Army Distinguished Service Medal to Second Lieutenant Sedgwick Rice, United States Army, for services against hostile Indians while serving with the 7th Cavalry near the Catholic Mission on White Clay Creek, South Dakota, on 30 December 1890.

Following are the citations of the remaining thirty-two soldiers who were recognized with Certificates of Merit and Honorable Mentions by the Commanding General of the Army but were not awarded medals for their actions.

December 29, 1890. Sergeant John F. Tritle, Troop E, 7th Cavalry: For conspicuously gallant and meritorious conduct in action against hostile Sioux Indians, at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota, where, though slightly wounded in the right hand, he continued his efforts until disabled by a severe wound in the right shoulder. (Certificate of merit.)

December 29, 1890. Nathan Fellman (then private, Troop K, 7th Cavalry, and now out of service): For special bravery after the action against hostile Sioux Indians, at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota, in voluntarily accompanying an officer carrying dispatches on a most dangerous and difficult trip. (Certificate of merit.)

December 29, 1890. Nathan Fellman (then private, Troop K, 7th Cavalry, and now out of service): For special bravery after the action against hostile Sioux Indians, at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota, in voluntarily accompanying an officer carrying dispatches on a most dangerous and difficult trip. (Certificate of merit.)

December 30, 1890. Privates Richard Costner and William Girdwood, Hospital Corps, U. S. A.: For gallantry in action against hostile Sioux Indians, near the Catholic Mission, on White Clay Creek, South Dakota, in taking the ambulance, abandoned by its civilian teamster, and rescuing a wounded officer under fire, on the battlefield. (Certificates of merit.)

December 6, 1890. Captain Ezra P. Ewers, 5th Infantry: For gallant and meritorious services in traveling 60 miles through a country infested by hostile Indians, accompanied only by Lieutenant Hale, 20th Infantry (then of the 12th Infantry), and entering the camp of Chief Hump, an Ogallalla Sioux, on Cherry Creek, South Dakota, at the time when the Indians in the camp were in an excited and dangerous condition, pacifying the Indians, and changing their attitude from one of hostility and distrust to one of peace and confidence.

December 6, 1890. Captain Ezra P. Ewers, 5th Infantry: For gallant and meritorious services in traveling 60 miles through a country infested by hostile Indians, accompanied only by Lieutenant Hale, 20th Infantry (then of the 12th Infantry), and entering the camp of Chief Hump, an Ogallalla Sioux, on Cherry Creek, South Dakota, at the time when the Indians in the camp were in an excited and dangerous condition, pacifying the Indians, and changing their attitude from one of hostility and distrust to one of peace and confidence.

December 6 to 24, 1890. 1st Lieutenant Harry C. Hale, 20th Infantry (then 2d lieutenant, 12th Infantry): For conspicuous courage, fortitude, good judgment, and tact in dealing with the hostile Sioux Indians at their ghost-dance camp near the mouth of Cherry Creek, South Dakota, which resulted in the surrender and disarmament of a large band of them.

December 18 to 24, 1890. Captain Joseph H. Hurst, 12th Infantry, commanding Fort Bennett, South Dakota: For courage and good judgment in dealing with a band of hostile Sioux Indians, followers of Sitting Bull, at Cherry Creek, South Dakota, detaching them from other hostile Indians, and conducting them to Fort Bennett, where they were disarmed.

December 23 to 26, 1890. Captain Peter S. Bomus, 2d Lieutenant Peter E. Traub, with Troop A, 1st Cavalry, and 2d Lieutenant Samuel Burkhardt, jr., 25th Infantry, in charge of Hotchkiss gun detachment, and the men of their commands: For energy and fortitude in a forced march of 186 miles, of which 95 miles were made in 25 hours from Fort Abraham Lincoln, North Dakota, to Curtis Ranch, Cave Hills, North Dakota, to succor a troop of cavalry reported to be surrounded by hostile Sioux Indians.

December 23 to 25, 1890. 1st Lieutenant John G. Ballance, 22d Infantry, commanding Company D; 1st Lieutenant Tredwell W. Moore, 9th Infantry (then 2d lieutenant, 22d Infantry); Adam Forster (then 1st sergeant, and now out of service) and the enlisted men of Company D, 22d Infantry: For energy and fortitude in a forced march of 116 miles, of which 63 miles were made in 29 hours and 15 minutes, from the Cannon Ball River to New England City, North Dakota, part of the time during a heavy snow storm, to relieve a troop of cavalry reported surrounded by hostile Sioux Indians in the Cave Hills, North Dakota.

Winter of 1890 to 1891. Lieutenant Colonel Dallas Bache, surgeon, U. S. Army: For conspicuous skill and good judgment as medical director in the operations against hostile Sioux Indians near Pine Ridge, South Dakota, in collecting and preparing, with the efficient and prompt support of the Surgeon General, all the means and appliances necessary for the excellent care given to the sick and wounded of that campaign.

Winter of 1890 to 1891. Lieutenant Colonel Dallas Bache, surgeon, U. S. Army: For conspicuous skill and good judgment as medical director in the operations against hostile Sioux Indians near Pine Ridge, South Dakota, in collecting and preparing, with the efficient and prompt support of the Surgeon General, all the means and appliances necessary for the excellent care given to the sick and wounded of that campaign.

December 30, 1890. Major Guy V. Henry, 9th Cavalry: For conspicuous gallantry and enterprise in action against hostile Sioux Indians, near the Catholic Mission, on White Clay Creek, South Dakota, and for efficient and distinguished services during the whole campaign.

December 30, 1890. Major Guy V. Henry, 9th Cavalry: For conspicuous gallantry and enterprise in action against hostile Sioux Indians, near the Catholic Mission, on White Clay Creek, South Dakota, and for efficient and distinguished services during the whole campaign.

December 29, 1890. Captain Henry J. Nowlan, 7th Cavalry: For gallant service in action against hostile Sioux Indians, at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota.

December 29, 1890. Captain Henry J. Nowlan, 7th Cavalry: For gallant service in action against hostile Sioux Indians, at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota.

December 29 and 30, 1890. Captain Allyn Capron, 1st Artillery: For gallant service in actions against hostile Sioux Indians, at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota, on the 29th, and near the Catholic Mission, on White Clay Creek, South Dakota, on the 30th.

December 29 and 30, 1890. Captain Allyn Capron, 1st Artillery: For gallant service in actions against hostile Sioux Indians, at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota, on the 29th, and near the Catholic Mission, on White Clay Creek, South Dakota, on the 30th.

December 29, 1890. Captain George D. Wallace, 7th Cavalry: For conspicuous gallantry in action against hostile Sioux Indians at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota, where, holding his ground against overwhelming odds, his death at the hands of the enemy terminated a notably honorable and useful career.

December 29, 1890. Captain George D. Wallace, 7th Cavalry: For conspicuous gallantry in action against hostile Sioux Indians at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota, where, holding his ground against overwhelming odds, his death at the hands of the enemy terminated a notably honorable and useful career.

December 29, 1890. 1st Lieutenant Horatio G. Sickel, 7th Cavalry: For gallant service in action against hostile Sioux Indians, at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota.

December 29, 1890. 1st Lieutenant Horatio G. Sickel, 7th Cavalry: For gallant service in action against hostile Sioux Indians, at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota.

December 30, 1890. 1st Lieutenant James D. Mann, 7th Cavalry (since deceased): For gallantry in action against hostile Sioux Indians, near the Catholic Mission, on White Clay Creek, South Dakota, where he was mortally wounded.

December 30, 1890. 1st Lieutenant James D. Mann, 7th Cavalry (since deceased): For gallantry in action against hostile Sioux Indians, near the Catholic Mission, on White Clay Creek, South Dakota, where he was mortally wounded.

December 29, 1890. 2d Lieutenant Guy H. Preston, 9th Cavalry: For courage and endurance in carrying, with remarkable speed, an important dispatch during the action against hostile Sioux Indians, at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota, from the battle-field to the Pine Ridge Indian Agency, over a road exposed to the enemy.

December 29, 1890. 2d Lieutenant Guy H. Preston, 9th Cavalry: For courage and endurance in carrying, with remarkable speed, an important dispatch during the action against hostile Sioux Indians, at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota, from the battle-field to the Pine Ridge Indian Agency, over a road exposed to the enemy.

December 29, 1890. Privates George Green and John Flood, Battery E, 1st Artillery, serving with mountain-howitzer detachment: For gallantry in action against hostile Sioux Indians, at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota.

December 29, 1890. Private Frederick George. Troop K, 7th Cavalry: For gallant and meritorious conduct in action against hostile Sioux Indians, in holding possession of captured arms, at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota.

December 29, 1890. James Christianson (then trumpeter, Troop K, 7th Cavalry, and now out of service): For coolness and bravery in action against hostile Sioux Indians, at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota, where he was severely wounded.

December 30, 1890, to January 1, 1891. Sergeant John McTigue (since deceased), commanding detachment 6th Cavalry: For courage and skill in carrying important dispatches on December 30, 1890, to January 1, 1891, passing twice through the lines of the hostile Sioux Indians, then encircling Pine Ridge Indian Agency.

December 30, 1890. Sergeant Emanuel Hennessee and Private Frank Mahoney, Troop G, 7th Cavalry: For conspicuous bravery and good conduct in front of the skirmish line in action against hostile Sioux Indians, near the Catholic Mission, on White Clay Creek, South Dakota.

January and February, 1891. Captain Jesse M. Lee, 9th Infantry: For highly meritorious services in successfully conducting a band of over 600 surrendered Brule Sioux from the Pine Ridge to the Rosebud Agency, South Dakota, without military escort and under peculiarly trying circumstances, during the most inclement period of a Dakota winter.

February 8, 1891. 2d Lieutenant Sydney A. Cloman, 1st Infantry, commanding Troop C, Ogallalla Indian Scouts: For the excellent judgment and discretion with which he executed the instructions of Major General Miles in the arrest, at White Clay Creek, South Dakota, of the Indian Plenty Horses.

February and March, 1891. Captain Ezra P. Ewers, 5th Infantry: For highly meritorious services in conducting a band of 370 Cheyenne Indians from Pine Ridge, South Dakota, to Fort Keogh, Montana, a distance of about 400 miles, accompanied only by 1st Lieutenants Lewis H. Strother, 1st Infantry, and Robert N. Getty, 22d Infantry, commanding troops of Cheyenne Scouts, under peculiarly trying circumstances, and during the most inclement period of a Dakota winter; the services of both Lieutenant Strother and Lieutenant Getty were also highly efficient on this march.

February and March, 1891. Captain Ezra P. Ewers, 5th Infantry: For highly meritorious services in conducting a band of 370 Cheyenne Indians from Pine Ridge, South Dakota, to Fort Keogh, Montana, a distance of about 400 miles, accompanied only by 1st Lieutenants Lewis H. Strother, 1st Infantry, and Robert N. Getty, 22d Infantry, commanding troops of Cheyenne Scouts, under peculiarly trying circumstances, and during the most inclement period of a Dakota winter; the services of both Lieutenant Strother and Lieutenant Getty were also highly efficient on this march.

January 29 to February 13, 1891. 1st Lieutenant (then 2d Lieutenant) Hugh J. Gallagher, 6th Cavalry; George W. Short (then corporal, Troop F, 6th Cavalry, and now out of service), and the enlisted men of the detachment: For highly meritorious services in successfully conducting 72 Indian prisoners, the remnant of Big Foot’s band, from the Pine Ridge Agency to Fort Bennett, South Dakota, under peculiarly trying circumstances, during the most inclement period of a Dakota winter.

A periodical of the day that detailed all of the soldiers honored in General Order 100 summarized the feelings of the nation toward its soldiers that served during the winter campaign of 1890 and 1891. The correspondent also provided a contemporary view–a view that is perhaps alien to Americans more than a century removed from the trials and tribulations of the frontier–of a democratic republic recognizing publicly its military soldiers with certificates, medals, or honorable mention.

It has ever been the despair of some that the United States government gave no mark of a distinguishing nature to those citizens who rose above their fellows by reason of superior mental ability, ingenuity, or courage. To be sure, this is a republic, and all its citizens are on an equality—before the law. However true the theory may be, practice shows that official commendation is a great stimulant of acts calculated to foster national pride; and it is a source of congratulation for all Americans that this government has receded somewhat from the extremist view. It does not award titles of nobility, nor does it bemedal its artists and authors, but it does show its appreciation of courage, gallantry, and devotion in its very limited military service by Congressional thanks, medals of honor, and certificates of merit.

….

It is such small matters, such doles from the public treasury, that make these brave men feel that, after all, the government has a regard for them. In a country inhabited by millions it is an easy thing to forget that a scant thousand commissioned officers and twenty-five thousand enlisted men are struggling with the military duty of the whole nation; they are such an insignificant fraction; they are not producers; they have no political function; they can have no homes; their best endeavors can produce but a sorry imitation of settled domestic life. They are ordered hither and thither; the wind of alleged “needs of the service” may take them to Texas in July and Dakota in January; they are play things, till some day their masters open their eyes in surprise to see that they are men who will die for a principle, or even for an order; who hold duty to be paramount to all earthly considerations; who, facing life and all it holds for them execute a military order “about face,” and march through death to the beyond uncomplainingly, so that some millions of people unknown to them, uncaring about them, may consider themselves safe and at peace. Honors to those who face death and return should not be grudged. It is not in a pecuniary way that the matter has value to them, but in the thought that, through the government, the people know them and respect them, and that there is a place in the heart of the people for them.

This does not apply with equal force to the commissioned and enlisted sides of the army. The officer may become tolerably well known; the private’s chance of it is not worth mentioning. It is possible that each soldier in the ranks carries a pair of shoulder straps in his knapsack, but he seldom finds them. But devotion to duty is not a matter of pay or position; it is as common in the ranks as among the officers; it is the rule from which none may swerve and live respected. And these marks of recognition of merit by the rifle or the sword come with a particularly good grace. The people can afford them, and the army appreciates them.[9]

Endnotes:

[1] Adjutant General’s Office, Official Army Register for March 1891, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891), 378-380.

[2] Adjutant General’s Office, Regulations for the Army of the United States 1895 with Appendix separately indexed, showing changes to January 1, 1899, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1899), 245.

[3] United States Congress, “Senate Document No. 58, General Staff Corps and Medals of Honor, July 23, 1919,” 66th Congress, 1st Session, Senate Documents Vol. 14, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1919), 141-281. I arrived at these figures through a detailed analysis of the tables listed in the 1916 review of Medals of Honor, which included 428 medals awarded during the Indian Wars.

[4] Ibid.

[5] This paragraph depict the official numbers for medals awarded to 7th Cavalry soldiers at Wounded Knee and Drexel Mission. However, my research has revealed that one soldier, Marvin Hillock, was erroneously cited for action at Wounded Knee, despite clearly being recommended for action at White Clay Creek. Thus, an accurate reflection of medals surrounding Wounded Knee is thirteen 7th Cavalry soldiers received the Medal of Honor for their actions at Wounded Knee, four for their actions at Drexel Mission on the White Clay Creek, one for actions in both battles, and two for their conduct during the entire campaign.

[6] War Department, Regulations for the Army of the United States 1889 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1889), 18.

[7] Spencer Tucker, ed., The Encyclopedia of North American Indian Wars, 1607-1890: A Political, Social, and Military History, Vol. 1, (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2011), 879.

[8] Adjutant General’s Office, “General Order No. 100, Headquarters of the Army, December 17, 1891,” General Orders and Circulars – 1891, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1892), 2-9; Adjutant General’s Office, “General Order No. 33, Headquarters of the Army, May 16, 1892,” General Orders and Circulars – 1892, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1893), 1.

[9] George I. Putnam, “Honors in the Service.” Harper’s Weekly, June 18, 1892: 582-583.

Citation for this article: Samuel L. Russell, “Gallantry In Action,” Army at Wounded Knee (Sumter, SC: Russell Martial Research, 2013-2015, http://wp.me/P3NoJy-4N), last updated 9 Nov 2014, accessed date __________.

Very grateful to you for bringing these original sources to the public!

I worked at Custer Battlefield for several years during the early 1980’s which gave me a strong background with military records & sources. I’ve long wished that someone could make available to the public & researchers like myself these reports, maps etc. of wounded Knee, so that the frontier Army was given a fair shot for once. Have the military inquiries been made available in a published or downloadable form yet?

LikeLike

Ah I find that his name was misspelled..it was Ilsley…found out much about him. Thanks anyway

LikeLike

“When the Indians made a sudden treacherous attack upon the troops …” Hard to know what to make of this. I’m reading American Carnage at the moment and have a more or less broad understanding of what transpired on 29 December, and the events leading up to it. I hope if I ever have to defend myself against an armed incursion of my home, while in a weakened condition brought on by starvation, having been reduced to it by the actions of my Government, no one calls it a ‘treacherous’ act.

LikeLike

When you’re surrendered, been moved under custody, and then while being disarmed you suddenly open fire into you’re captors, they are quite right to call it treachery. The time for resisting was the day before, probably by dispersal and escape. They certainly weren’t so “weak” that they couldn’t show an aggressive front when the 7th cavalry first made contact.

LikeLike

Many questions exist why those among the 7th Cavalry said their actions were on revenge for the Little Big Horn or why so many women and children were killed and why those who fled Wounded Knee were chased and gunned down over two miles from Wounded Knee?

LikeLike

American soldiers heroically slaughtered Native American women and children (and elders)? Tell the truth!

LikeLike

I have an original photograph of a trooper F troop 7 th. cav. who has combined his marksmanship awards with part of a medal of honor. Wondered if you would like me to e-mail you a copy for your blog? No identification but photographers stamp is Philip S. Walton

LikeLiked by 1 person

Certainly. You can email me at Sam_Russell@RussellMartialResearch.com

LikeLike

My great grandfather, Nimrod Caple was conscripted into the army as a teamster in 1890 in Keystone, specifically to drive the cook wagon as they went after Sitting Bull’s followers. He was only in until 1891. During that time, on Jan.1, 1891, his wife gave birth to a son, alone in the gold fields. My great grandparents were never okay again.

LikeLike