Don’t fire, let them go, they are squaws….

Here come the bucks; give it to them!

Photograph of Henry J. Nowlan from Memorials of Deceased Companions of the Commandery of the State of Illinois, Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States.[1]

Capt. Nowlan brought I Troop to Wounded Knee with almost all of its authorized officers and soldiers; he was short one corporal and one private. Of his privates, nine had arrived from the recruiting depot during the campaign three weeks earlier, meaning that 20% of his privates were green soldiers with less than a month in the troop. Nowlan’s first lieutenant was W. J. Nicholson, who had served for six years at that rank and had been with the regiment for fourteen years, joining it a couple of months after the Little Big Horn. During the fight at Wounded Knee, Nicholson served as Major S. M. Whitside’s acting battalion adjutant. The I troop second lieutenant was J. C. Waterman, a thirty-three-year-old West Pointer who had been with I Troop since graduating from the academy in 1881. Jacob Trautman was Nowlan’s first sergeant, a twenty-seven year veteran who had served as the troop’s senior non-commissioned officer for the past decade and had joined the regiment a month after the Little Big Horn.[2]

At Wounded Knee, Capt. Nowlan’s troop suffered four soldiers killed and six wounded, of which three later died. Another soldier was wounded the following day at White Clay Creek, resulting in a 19% casualty rate among the I Troop enlisted men. The killed included Blacksmith Gustav Korn–a veteran of the Little Big Horn–and Privates Pierce Cummings, James Kelly, and Bernhard Zehnder. Those who died of wounds were Sergeant Henry Howard, Corporal Albert Bone, and Private Daniel Twohig. The other wounded were Sergeant Loyd George, Farrier Richard Nolan (White Clay Creek), and Privates Hipp Gottlob and Harvey Thomas.[3]

Capt. Nowlan was the second of four officers to testify on January 10, 1891, the fourth day of Maj. Gen. N. A. Miles’s Wounded Knee investigation.

Cropped from “Officers of the 7th Cavalry, Pine Ridge,” 1891. This is the only photograph showing Capt. Nowlan from the time of Wounded Knee, his distinctive sideburns appearing completely gray.[4]

Captain H. J. Nowlan, 7th Cavalry, was then called in, and having been duly sworn, testified as follows, in answer to questions:

I commanded Troop I, 7th Cavalry, in the engagement with Big Foot’s band of Indians on the 29th of December, 1890. It came under my personal observation during that day that it was the cry all over the field, both on the part of officers and enlisted men, not to kill women or children – “Don’t fire, let them go, they are squaws.” I still further state that from the position I occupied on the far side of the ravine, I saw the Indians come towards us into the ravine and go up and down it. The first mass of people that came down into the ravine, directly in my front, were squaws and children. I positively state that not a shot was fired into them by my own or other parties that I could see, except the fire of their own people; but that they were allowed to escape. But immediately following behind them came the bucks, and then the cry came from myself and the men around me, “Here come the bucks; give it to them,” and our fire was returned by the bucks.[5]

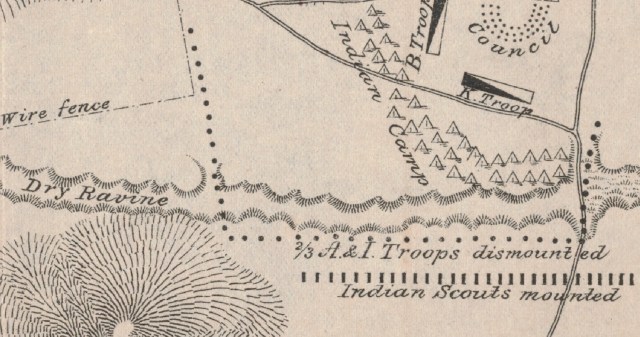

(Click to enlarge) Inset of Lieut. S. A. Cloman’s map of Wounded Knee depicting the scene of the fight with Big Foot’s Band, December 29, 1890. Capt. Nowlan was positioned on the south side of the ravine where the map says “2/3 A & I Troops dismounted.”

The investigators then asked Capt. Nowlan if he thought the troops were “judiciously located,” given the work to be done. He responded, “Yes, sir, I do; so much so that with the overwhelming number we had there to disarm the Indians, I did not suppose, that any human beings would have the temerity to make even an attempt to break away from us, and their effort to do so was a complete surprise to me.”[6]

Following the campaign, Private Walter R. Crickett recorded in a letter his recollection of his troop commander’s actions. “They made a break for a ravine just were we was posted and kept up a running fire, but by the time they reached the ravine there was dozens down. The man that stood next to me was shot down in the first discharge. I fired at the Indians at the same time but only struck him in the leg. He returned my fire and struck my revolver which knocked me down, which saved me but if it hadent been for the pistol I should of got it through the thigh, but he dident go much farther out. Capt. (Nolan) shot him through the heart.”[7]

(Click to enlarge) Adjutant General’s Office referred Col. J. W. Forsyth’s brevet promotion recommendations to Maj. Gen. N. A. Miles for remarks.

Crickett was not the only one to make notice of Capt. Nowlan’s actions that day. Col. Forsyth recommended five officers, including Nowlan, be awarded brevet promotions for their conduct at Wounded Knee. These recommendations eventually found their way to Maj. Gen. Miles, who initiated an investigation into acts of gallantry, heroism, or fortitude at the battle. On October 20, 1891, Miles’s inspector general, Col. Edward M. Heyl, took the following testimony from Captain Nowlan regarding his recollections of the fights at Wounded Knee and White Clay Creek.

I was with Major Whitside’s battalion when Big Foot came in, or surrendered. We received orders on the morning of December 28th to saddle up, and marched out of camp about six or seven miles. I saw a body of Indians about one-half mile off displaying a white flag. We dismounted to fight on foot. The Hotchkiss guns were placed in the centre, and the troops on each flank. Big Foot was in a wagon, and Major Whitside went forward to meet him, and after a short talk the Indians were placed under guard and marched back to the 7th Cavalry camp at Wounded Knee.

….I saw Major Whitside several times. He was on foot directing the movements of part of the command. I cannot specify any special acts of conspicuous gallantry on the part of Major Whitside, but I noticed, particularly, the manner in which he exposed himself to the Indians’ fire.

On arriving at Lieut. Sickel’s party to deliver an order, I found Lieut. Rice there trying to encourage the men. Lieut. Gresham rendered me a great deal of assistance while on the line. He was exposed to a very severe fire during the whole time and acted in a very gallant manner.

Three men of my troop, “I”, were recommended for acts of gallantry, and have received medals. 1st Sergeant Troutman, Far. Nolan and Sergeant Loyd.

Captain Capron’s (Battery E, 1st Artillery) conduct at the Mission fight was conspicuous and cool. I saw him sighting the guns himself as well as directing the fire. I was supporting his battery at the time.

I saw Assistant Surgeon Hoff attending to the wounded about the close of the Wounded Knee fight. I saw him at the Mission fight, his conduct was cool and conspicuous and gallant in bringing his ambulance up under a hot fire to attend to some men who were wounded of my troop. He dressed the wounds and helped off the field a wounded man where the fire was very hot on the skirmish line.

I noticed Major Whitside at the Mission fight, his conduct was conspicuous throughout. I noticed him particularly as he was in command of my battalion at that time.[7]

During the course of the investigation, several officer’s provided testimony regarding Capt. Nowlan’s conduct at the fights along the Wounded Knee and White Clay creeks. Lieut. S. Rice told Col. Heyl, “I saw Captain Nowlan while we were engaged with the Indians in the ravine. He came up dismounted with an order from Colonel Forsyth, exposing himself to the fire of the Indians all the time. Captain Nowlan stayed with us on the skirmish line until it was withdrawn.”[8]

Lieut. J. W. Nicholson of Nowlan’s troop stated, “I saw Captain Nowlan, Troop “I”, 7th Cavlary, at Drexel Mission December 30th, 1890. He was on the left of the line, and with six or seven men charged the crest of the hill, and dislodged the Indians who were annoying Captain Varnum’s line.”[9]

Lieut. E. P. Brewer commented, “I also saw Captain Nowlan, he was in a very conspicuous place, so much so that I sent his sergeant to tell him there were some Indians to his right and rear, that would shoot him. This was during the hottest part of the fight.”[10]

Capt. W. S. Edgerly testified, “I noticed several officers under fire who behaved with coolness and bravery, but their acts were not specially conspicuous. They were Nowlan, Lieut. Gresham and Lieut. Brewer.”[11]

Finally, Maj. S. M. Whitside testified, “I noticed Captain Nowlan, 7th Cavalry, at a certain stage of the fight. It was reported to me that a number of Indians had passed into a ravine close by. Captain Nowlan had his troop standing on the right of it waiting for orders, dismounted. I directed him to proceed, double time, to the ravine where the Indians were reported to be, and make a thorough search for any Indians that might be there. Although under a fire from another ravine, he moved with the greatest coolness, and gave his orders intelligently and deliberately. He acted as if on parade. His coolness was conspicuous, so much so that he attracted my attention by his conspicuous conduct.”[12]

The brevet recommendation led to the Commanding General of the Army, Maj. Gen. J. M. Schofield, to consider Capt. Nowlan for honorable mention in general orders, along with dozens of other officers and soldiers from the campaign. The Adjutant General’s Office had the task of compiling the proposed honorable mentions and verifying the recommended conduct with official records and letters of recommendation. The original phrasing of honorable mention recommended for Capt. Nowlan mirrored the recommendation for a brevet promotion to major that Col. Forsyth submitted, “For conspicuous coolness and courage under fire, in the disposition and management of the men under his charge during the action against hostile Sioux Indians at Wounded Knee Creek.” Lt. Col. Merritt Barber, Assistant Adjutant General, initially indicated On December 3, 1891, “In view of the endorsement of Major General Miles of Nov. 18th, 1891, on these papers, Maj. Gen’l. Schofield decides not [to] include this officer at present.” However, Gen. Schofield reversed his decision in the case of Nowlan. Writing four days later, the Adjutant General recorded, “Approved for hon. men. for gallantry in action—in view of the controversy regarding this action that phrase will be used.” Apparently Gen. Schofield found this wording still to strong. Lt. Col. Barber added “On recommendation” to the front of the sentence and changed “gallant” to “gallant service.”[13]

Nowlan received honorable mention in General Order No. 100 dated December 17, 1891.

Henry James Nowlan was born on the Greek island of Corfu, on June 17, 1836 or ‘37, to Irish parents John Nowlan and Mary Bowman. Henry Nowlan’s British military records indicate he was born in 1836 while his American records state 1837. Henry was the second of three boys. His older brother, John, was born a decade earlier in 1826 or ‘27 in Ireland, and the youngest brother, Edward, was born a decade after Henry, between 1845 and ‘48 in Manchester, England. John Nowlan, the father, was born in Doon, County Limerick, Ireland, in 1792 and was a British soldier serving as a colour-sergeant in the 11th Regiment of Foot stationed in the Ionian Islands when Henry was born. Little is known of Henry’s mother. Nowlan indicated on the 1880 U. S. Federal Census that both his parents were born in Ireland, but nothing in his records indicates her name. Mary Bowman’s maiden name is recorded only on the older brother John’s marriage entry in a Dublin parish registry, and her first name is listed on an Australian death index for the younger brother Edward. So far, no record has turned up showing when or where Mary was born, when or where she and John Nowlan were married, whether there were any other children, and when or where she died. Far more is known of the Nowlan father.[14]

Capt. John Nowlan’s campaign medals included a Military General Service 1793-1814 with 4 clasps: Nivelle, Nive, Orthes, Toulouse; Crimea 1854-56 with 1 clasp, Sebastopol; and Turkish Crimea, Sardinian issue. Although Nowlan’s records indicate credit for Alma and Inkerman clasps, his Crimea campaign medal displays only the clasp for ‘Sabastolpol.’ Henry J. Nowlan was awarded the two campaign medals shown on the right.

John Nowlan’s British military service began by 1813 when he was about twenty years old. He enlisted in the 11th Regiment of Foot when it was known as the North Devonshire Regiment and served in several of the later battle’s of the Duke of Wellington’s Peninsula Campaign during the Napoleonic wars. Specifically he served at the battles of Nivelle in November 1813, Nive in December, Orthez in February, and Toulouse in April 1814. In 1815, Nowlan was assigned with the regiment’s 1st battalion to a post at Cashel in Southern Ireland where he reenlisted in 1816. He was listed as just over six feet tall with a fair complexion, hazel eyes, brown hair and a round visage. Nowlan was promoted to corporal in September 1820, to sergeant in April 1823, and to colour-sergeant at Cork, Ireland, in November 1825. He was assigned to the island of Corfu in the Ionian Sea in 1827 where the British maintained six barracks to house almost 3,000 troops stationed there. Nowlan was posted to Canada in 1838 and commissioned, without purchase, as an ensign (equivalent to a second lieutenant) in the 11th Foot in November 1840. He was transferred to the 77th Foot in October 1841 as a quarter-master and returned to various posts in England and Ireland in 1843. Nowlan was transferred to the 62nd Regiment of Foot as quarter-master and served with that unit during the Crimean War. On January 27, 1857, Quarter-Master John Nowlan of the 62nd Foot retired on half pay with the honorary rank of Captain, under the Royal Warrant of December 17, 1855. In retirement, he lived in Dublin where his wife, Mary, may have died in April 1865. Nowlan then married the widow Frances Duhigg Harrison, née Roberts, on November 10, 1865. The second marriage was a short one, for John Nowlan died April 9, 1866, leaving his estate to Frances, who survived him by two decades. She died in 1894.[15]

(Click to enlarge) Record of Henry J. Nowlan’s commission from the Royal Military College at Sandhurst.[16]

On September 14, 1854, the 41st Foot along with the remainder of the English and French armies landed near Lake Kamishlu in the Crimea. Ens. Nowlan was unable to join his already deployed regiment for several months. His father and older brother were present in the Crimea from the onset, John Nowlan Sr as the Quarter-Master of the 62nd Foot and John Nowlan Jr as the Paymaster of the 50th Foot. Both were credited with participating in the battles of Alma on September 20 and Inkerman on November 5. None of the Nowlan mens’ records mention Balaclava. Because of heavy losses in the officer ranks across the British regiments, promotions came quickly. Henry Nowlan, still waiting to join his regiment in the Crimea, was promoted to lieutenant, without purchase, on December 8, 1854. He finally joined the Crimean campaign at the end of January, and reported to his regiment on February 6 along with a draft of ninety-eight replacement soldiers from Templemore, Ireland. The teenage lieutenant was in the Crimea less than six months, but was credited with being at the Battle of the Great Redan, the day after Nowlan’s nineteenth birthday. His service qualified him for the Crimea War medal with the ‘Sebastopol’ clasp and the Turkish War medal awarded by the Ottoman Empire to her allies during the war. Neither medal was awarded for gallantry as some historians have erroneously stated. Almost two decades later Nowlan was photographed in his 7th Cavalry dress uniform adorned with both of his campaign medals.[18]

One of Nowlan’s peers, Lieutenant Byam, who had just joined the 41st Foot at the siege of Sevastopol on June 16, 1855, described the Battle of the Great Redan in letters home:

(Click to enlarge) “Capture of the Malakoff Tower.” The French briefly held their objective, but the British were unable to take the Great Redan on June 18, 1855. Lieut. Nowlan of the 41st Foot participated that day, but was not present in September when the Russian stronghold fell.[19]

Directly daylight began, the Russians opened a heavy fire upon us and the batteries; immediately the French, who were the first, commenced on the Round Tower. In the meantime we were in the trenches waiting to be moved forward, the grape, round shot and shell flying about us in style, as we were immediately between one of our battalions and the Redan. We were to have advanced when the French had taken the Round Tower, as that commanded the Redan, but they failed altogether; they once hoisted their flag on the top and two companies were in, but they were not supported, and consequently were taken prisoners. Then, through some mistake, a few of the light division were advanced into the Redan and were repulsed with frightful loss, some officers being even killed on the scaling ladders. It was a failure throughout, in consequence of several mistakes and the Russians being perfectly aware of what we were about (as they have since told us); besides, not half enough men were sent on. They moved us up out of the trenches about eight o’clock amidst a shower of grape and musketry. Our Lieutenant-Colonel Goodwyn had a slight wound on the forehead from a piece of shell, and we had one man killed and a few wounded. The poor fellow was sitting next to me when killed by a piece of shell. On Monday morning we were told off for the trenches, nine officers and nearly four hundred men. We were just in the advanced trench within two hundred yards of the Redan, with orders, as soon as it was dark, to go out and bring in the ladders and wounded men. We had just done so without being found out, the Russians being so busy repairing damages, that we went close up to the ditch to get the ladders, when they opened a tremendous fire for about a quarter of an hour or more. The firing was so sharp that the army was under arms immediately, and the old Crimean officers say they never heard anything like the firing, and that it was even sharper than Alma or Inkerman.[20]

Lieut. Nowlan served with the 41st Foot in the British West Indies–Trinidad, Barbados, and Jamaica–for two years from March 1858 to April 1860. Perhaps disillusioned by his inability to purchase a captain’s commission, and being the most senior lieutenant in his regiment for three years, Nowlan is recorded to have sold his commission in May 1862.[21]

With having sold—or ‘sold up’—his commission, Nolan immigrated to New York where he joined the 14th New York Cavalry Regiment in January 1863, perhaps seeking more rapid advancement in the officer ranks of the Union Army during the Civil War. Nowlan’s ambitions for wartime promotion were dashed less than six months later when he and his command were captured during the siege of Port Hudson.[22]

The 14th N. Y. Cav. were serving as part of Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks’s 1863 Red River Campaign. Nowlan was serving as a first lieutenant and in command of Company A, located near Brashear City, Louisiana. Official records state that he and his command were captured on June 15, 1863, Nowlan stated in a letter to the Secretary of War Stanton that it occurred on June 18, but this Chicago Tribune article puts the event a week earlier.[23]

Nolan, as he spelled his name during the Civil War, served in A Company, 14th New York Cavalry, when captured in 1863 near Port Hudson, Louisiana.[24]

On the 11th ult., five companies of the 14th New York cavalry, Col. Thaddeus B. Mott, doing outpost duty near Port Hudson, were captured by a daring cavalry raid of rebels, under the command of [Lieut.] Col. [John L.] Logan, of Bragg’s command, while encamped within three miles of Gen. Banks’ headquarters.

The capture was owing to the negligence of the officer (Capt. Porter, we are informed), who should have posted and attended to the picket guard. It seem that the guard were either never posted, or were at that time fast asleep, for in the middle of the night the Rebels rode into the Union camp, surprised the Unionists, roughly awakened them, ordered them to saddle up, and actually under the very nose of the Commander-in-Chief, run off five companies of our cavalry, with all their horses, arms and equipments.

The rebels made them ride at speed for 38 miles, making but one stop in that distance. When a horse gave out they entered a farmer’s premises and impressed another. At the journey’s end, our soldiers were thrown into a black hole, where, at last accounts, they were under close confinement.

The companies were Co. G, under command of Capt. Porter; Co. A, under Lieut. Nolan; Co. C, under Lieut. Leroy Smith; Co. F, under Capt. Thayer, who himself alone escaped, and the greater part of Co. E, under Capt. Ayers. Lieut. Vigel was also captured with Lieut. Smith’s men.

These five companies were under command of Maj. Mulvey, who was taken with his little boy, twelve years old. This boy, Michael Mulvey, was sent back within our lines by Gen. Bragg, to bring us the news….[25]

There is no specific mention of the capture of these five companies of cavalry in the War of the Rebellion Official Records, either from Union or Confederate reports. However, an exchange of correspondence between Brig. Gen. W. H. Emory and Maj. Gen N. P. Banks may reference it indirectly. Writing on July 3 from his headquarters at New Orleans, Emory stated, “The enemy have sent a flag of truce from Des Allemands Bayou, saying they have 1,200 prisoners they wish to deliver. Where they came from I do not know.” Banks replied two days later, “The prisoners referred to in your letter are doubtless the garrison and convalescents captured at Brashear City. This was a most discreditable affair to the officers in command. It would have been impossible, with any watchfulness whatever, for the enemy to prepare his rafts and crossed the waters above the city without such notice as to have enabled them to escape.”[26]

A review of the 14th New York Cavalry roster provides a different picture than the newspaper article. Rather than capturing five companies of cavalry with all equipment and horses, the roster reflects that two officers, Lieutenants Nolan and Smith, and forty-four enlisted men were captured, twenty-two from F, fourteen from G, six from C, and two from A companies. All of the enlisted men were paroled two weeks later on July 2 at City Point, Virginia. Nolan and Smith remained in confinement until the two escaped from prison around March 1865.[27]

(Click to enlarge) Capt. Nowlan was a prisoner at Columbia, S. Car., possibly at Camp Sorghum, when he escaped and joined Gen. Sherman’s march through the Carolinas.[28]

Capt. R. G. Richards, 49th Pennsylvania Infantry, was held at the Columbia jail and related his account of several escapes, including two officers who made it into Gen. Sherman’s lines.

The thought uppermost in the minds of the prisoners was to devise ways and means of escape, and their ingenuity and engineering skill were always exercised in that direction. In a short time after we were incarcerated in that filthy den, two of our number were enabled to escape, one very dark night, by being let down out of the front window onto the sidewalk below, and within ten feet of a guard, who stood in the recess of the main entrance. One (Lieutenant Williams) arrived safely within our lines near Beaufort, S. C. The fate of the other is unknown. They were let down by a sort of wooden rope, made by tying together strips of wood.[30]

Nowlan made his escape in February or March 1865 after twenty-one months of confinement, and made his way into Sherman’s lines. Whether he was aware or not, during his captivity, Nowlan was promoted to Captain in August 1863, to date from the previous February. Capt. Nowlan served with the staff of the 15th Corps through the rest of Sherman’s campaign through the Carolinas and eventually rejoined his regiment two months later in New Orleans. He was transferred to command of Company K, 18th New York Cavalry, and posted to Texas on reconstruction duties in January 1866. It was on that assignment that Nowlan almost lost his life. An article in the San Antonio Herald and carried in several other papers recorded the events of March 8, 1866.[31]

Capt. Nolen, 18th New York Cavalry, was detailed to arrest one Porter, a desperate character, who had killed an old gentleman last August, and whom Gen. Stanley had issued an order at the time, ordering any officer, civil or military, to arrest. The son of the murdered man reported to Capt. Nolen that Porter and his party would be at a neighbor’s house on a certain night to attend a wedding.

The captain proceeded to the house with a file of sixteen soldiers, and as soon as he entered the house, put his hand on Porter’s arm and ordered him to surrender, whereupon a man stepped up and shot the Captain through the wrist; the Sergeant of the detail promptly shot the rascal dead in his tracks, when Porter drew his pistol and fired at Captain Nolen, the ball entering his breast near the heart and coming out between the shoulders; the Captain drew his pistol and shot Porter dead and mortally wounding two others. At this time the soldiers were in line and were about to fire a volley on the crowd–when Capt. N. told his men “not to kill the women, for God’s sake.” Twenty-one of the men were arrested and were to have reached this place last night, under guard. Capt. Nolen was not dead at last accounts, although his recovery is almost impossible; a physician started from here on Sunday to attend upon him.[32]

Conditions were indeed critical for Capt. Nowlan in the aftermath of the gun fight. Reporting less than a week afterward, Brig. Gen. J. Shaw, commanding the Central District of Texas wrote, “Brevet Major Kelly, fourth United States cavalry, who was present soon after Captain Noolan was shot, near Yorktown, reported on his return that there was great danger of the captain being murdered while lying there wounded, and unless a large force were sent down, Anderson [one of the men wounded and arrested] would be rescued as soon as he was able to move.” However, Nowlan’s wound was not mortal and he recovered rather quickly. Writing less than two weeks later from Yorktown, Texas, Capt. Chesbrough of the 18th N.Y. Cav., reported, “Captain Nowlan is still here–is improving very fast, and will be in a short time able to move about.” Maj. Davis, who was commanding the detachment of 18th Cav. at Yorktown reported on March 29, “I have the honor to forward you a prisoner named Wat. Anderson, who has been in custody in Clinton and Yorktown since the night of the affair in which Captain Nowlan was shot. The man Anderson is the man who grabbed Captain Nowlan by the arm, at the time he was shot. He is a notorious character, and is one of the leaders of a band of desperadoes that have been infesting this part of the county.” Nowlan’s tribulations were not yet over. Traveling by ambulance from Yorktown to San Antonio along with another wounded civilian and the prisoner Anderson, two soldiers from the party who had halted to rest their horses were waylaid. While waiting for the soldiers to catch up, “two teamsters overtook them [Nowlan’s party] and reported that the two [soldiers] were shot dead and lying on the road.” The fate of Anderson and the other “desperadoes” is not listed in the Congressional records. Nowlan was mustered out of service at the end of May 1866 at Victoria, Texas. [33]

Lieut. H. J. Nowlan, 7th U.S. Cavalry, wearing dress uniform with 1872 model cavalry helmet and his two campaign medals from the Crimean War.[35]

Of all the officers in the newly formed regiment, Lieut. Nowlan’s closest friend was fellow Irishman Capt. Myles W. Keogh. Almost six years his junior, Keogh was born in Carlow, Ireland, and had served as an officer in the Papal Army before immigrating to America to join the Union. By November 1867, Keogh commanded I Company, 7th Cav., and held brevet promotions to major and lieutenant colonel. In an 1867 letter to his brother, Keogh wrote of his new friend Nowlan, he is “quite handsome and exceedingly passionate… He will come to Ireland with me next year.” Keogh went on to write, “I am living with Nowlan and I find he is engaged to be married… to a sweet girl. He seems to like being in love.” What became of Nowlan’s betrothed is unknown, for he never married.[36]

Nowlan was quickly promoted to first lieutenant in August 1867, to date from December the previous year. Assignments with the 7th Cav. saw Nowlan in numerous duties, as acting commissary, acting adjutant, acting regimental quartermaster, post commissary, etc. In August 1871, he was in command of L Company and posted to Winnsboro, South Carolina, not far from where he had been held prisoner during the war seven years earlier.[37] His brief assignment in the post-reconstruction South brought him into conflict with the Ku Klux Klan. Writing from his post at Winsborro, Nowlan informed his higher headquarters at Columbia of the following incident. It shows his frustration with not being able to engage civilian criminals and the inability to get local authorities to take action:

On the night of July 29th a party of men (number unknown) set fire to and burned the school house at Feasterville… about 18 miles north west of this place. A colored man named “Alick Des.” and his wife, living near the school house, being attracted to their door to witness the fire, were shot at, one of the shots taking effect wounding the man and killing the woman. I cannot learn the names of any of the persons engaged in this outrage, but believe it to have been committed by members of the Ku Klux organization as the people appear to be intimidated and afraid to give evidence. It does not appear that an inquest was held after the occurrence, nor can I ascertain that the county authorities have taken or intend taking any steps to investigate the matter. Having no authority to act in a case of this kind, except in conjunction with the civil authorities, I consider it advisable and would recommend that the U. S. Marshal or his Deputy be directed to investigate this case with as little delay as possible….[38]

“Comanche (horse) and Captain Keogh (separate pictures made into one plate) full length” from the Denver Public Library Digital Collections.

Nowlan was appointed the Regimental Quartermaster in March 1872 and served in that position for the next four years at various posts. In that capacity, he was serving as the post quartermaster at Fort Lincoln, Dakota Territory, when the 7th Cavalry departed on its fateful expedition in 1876. Nowlan was detached from the regiment, serving as the acting assistant quartermaster for Brig. Gen. A. H. Terry, thus he was not in the fight at the Little Big Horn. He arrived on June 27 and with a detachment under the command of Capt. F. W. Benteen, searched the carnage of Lt. Col. G. A. Custer’s last battlefield. There he found the body of his best friend, Myles Keogh, stripped of clothing but left unmutilated. Nowlan also recognized Keogh’s mount, Comanche, who had several serious wounds but had survived the battle. Nowlan ensured Comanche was cared for and placed onboard the steamship taking wounded back to Bismarck and eventually to Fort Lincoln.[39]

In the wake of so many casualties among the officers of the regiment, Nowlan was now the senior first lieutenant and promptly promoted to captain along with James M. Bell and Henry Jackson. Perhaps in recognition of their close friendship, or merely by coincidence, Nowlan filled the vacancy created by the death of Keogh, and became the commander of I Company.[40]

The following summer Capt. Nowlan returned to the Little Big Horn battlefield as part of an element sent to bring back the remains of several officers, including those of Keogh. The young Irish cavalry officer was buried in Fort Hill Cemetery, Auburn, New York, later that year. Nowlan was unable to attend as he was actively campaigning.[41] In September, Nowlan and his Company I formed part of Maj. Lewis Merrill’s battalion of the 7th Cavalry under Col. S. D. Sturgis that fought against Chief Joseph’s Nez Perce Indians. Nowlan had fifty-one enlisted men and Lieut. E. P. Brewer with him. The battalion also consisted of Capt. Bell’s Company F and First Lieut. Wilkinson’s Company L. Merrill recognized Nowlan and most of the officers that fought that day. Eventually in 1893 all the officers, excepting Wilkinson who died in 1892, were awarded brevet promotions based on Merrill’s report.[42]

I cannot too highly commend the conduct of both officers and men, the latter especially, mostly recruits, for the first time engaged, and under a fire which was frequently severe, and always delivered by the Indians from well-sheltered positions, where it required both exposure and good shooting to return with any effect. They fought on foot over some eight miles of difficult and intersected ground, on the heels of a forced march of 80 miles, almost without rest and on half rations, and this preceded by two days of severe exertion, during which 70 miles, chiefly of mountain climbing, had been covered, and men and horses were pushed to the very verge of physical endurance, yet there was not seen a falter or moment’s need of urging forward. Captain Nowlan, Captain Bell, and Lieutenant Wilkinson, commanding companies, handled their men with skill and courage, constantly exposing themselves in encouraging and giving examples to their men…. Among the enlisted men I especially commend Sergeant Costello, of Troop I, who executed, with great skill and courage, my order to scale the bluff of the Cañon, and whose success saved us great loss in advance up the Cañon.[43]

On September 18, 1890, while detached on recruiting service in Chicago, Nowlan became a naturalized U. S. citizen. He rejoined his company and regiment at Fort Riley two months later in time to depart to Pine Ridge, South Dakota.[44]

Following that sanguinary winter campaign, Capt. Nowlan continued in command of Troop I at Fort Riley. Comanche, the mount of Nowlan’s old friend Keogh, that had survived the Battle of the Little Big Horn, was still serving in Nowlan’s company. The old war horse had gone with his troop to Pine Ridge and may have been present at Wounded Knee where his caretaker, Blacksmith Korn, was killed. By the following summer the renowned horse was not well. Nowlan revealed in a letter, “I fear the famous horse will not last much longer.” Comanche died of colic on November 6, 1891. According to fellow 7th Cavalry officer Edward S. Godfrey, Nowlan gathered the officers and decided to allow Professor Dyche, a naturalist at the University of Kansas, to mount Comanche’s remains and retain him at the university in Lawrence.[45]

In December 1891, when Capt. Nowlan was recognized for gallantry at Wounded Knee in General Order No. 100, he was assigned as the acting assistant inspector general for the Department of the East and served in that capacity until the summer of 1894. By the following summer he was again with Troop I commanding the sub-post of San Carlos, Arizona Territory. By then he was the senior captain in the Cavalry and was promoted to major in July 1895. Serendipitously, he filled the vacancy created when Maj. S. M. Whitside of the 7th Cavalry was promoted to lieutenant colonel, effectively keeping Nowlan in that storied regiment without having to request a transfer.[46] The promotions from within the 7th Cavalry, even by the mid-1890s, were still effected by the large casualty rate from the Little Big Horn two decades earlier.

An order has been issued by Secretary Lamont retiring Lieutenant Colonel George A. Purington, Third Cavalry… The retirement promotes Major Samuel M. Whitside to be Lieutenant Colonel; Captain Henry J. Nowlan to be Major; First Lieutenant Lloyd S. McCormick to be Captain…. Whitside, Nowlan, and McCormick all belong to the Seventh Cavalry, and it is noticeable that the next promotions, both to Major and Captain, will be in that regiment. Captains Nowlan, Bell, and Henry are the three ranking captains of the army, and all are in the Seventh. All received their last promotions on the same day, June 25, 1876. That was the day that Custer and a portion of the Seventh Cavalry were wiped out on the Little Big Horn by Sitting Bull’s band of Sioux.[47]

By the summer of 1896, Major Nowlan, now sixty years old, was commanding Fort Huachuca. It would be his final assignment. Over the next two years he felt the effects of heart disease and departed on leave on a surgeon’s certificate in October 1898. He was authorized to seek treatment at the Army and Navy Hospital at Hot Springs, Arkansas, where he died November 10. Being a single officer with no known family, he was buried in the Army cemetery at Little Rock.[48]

Major Henry J. Nowlan is buried in the Little Rock National Cemetery in Arkansas.[49]

Nowlan’s older brother, John, died in 1892, but his younger brother, Edward, was still alive. Nowlan had filed a will in Washington, D.C., in 1897 in which he left all his property to “my only living brother, Edward David Nowlan,” living in New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. Nowlan’s will stipulated that, “all my personal belongings (except my personal (private) papers, which I request may be forwarded to him) be sold and the proceeds sent to him.” However, Henry Nowlan also had a niece and nephew of his brother, John, still living in Ireland. Maude Nowlan and her brother Thomas Bowman Nowlan contested the will in 1899. The case was not yet resolved when Edward Nowlan died in 1900 and was still in the courts in 1901. Whether or not Maude and Thomas Nowlan prevailed in contesting the will is not known. Maude died in 1920 unmarried, and Thomas died in 1929, leaving a widow but no children.[50]

Of interest to the historian is what became of Major Nowlan’s private papers that he requested be forwarded to his only living brother. Did they end up going to his niece or nephew in Ireland? Little has been published about the life and career of Henry James Nowlan, and those papers would certainly help to shed light on an otherwise “anonymous” Custer officer.

Endnotes:

[1] “Henry James Nowlan,” Memorials of Deceased Companions of the Commandery of the State of Illinois, Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS: Chicago, 1901), 397.

[2] Adjutant General’s Officer, “7th Cavalry, Troop I, Jan. 1885 – Dec. 1897,” Muster Rolls of Regular Army Organizations, 1784 – Oct. 31, 1912, Record Group 94, (Washington: National Archives Record Administration).

[3] Ibid.

[4] A. G. Johnson, pub., “Officers of the 7th Cavalry,” Denver Public Library Digital Collections, [https://digital.denverlibrary.org/digital/collection/p15330coll22/id/24410/rec/33] accessed 12 Sep 2020.

[5] Jacob F. Kent and Frank D. Baldwin, “Report of Investigation into the Battle at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota, Fought December 29th 1890,” in Reports and Correspondence Related to the Army Investigations of the Battle at Wounded Knee and to the Sioux Campaign of 1890–1891, the National Archives Microfilm Publications (Washington: The National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration, 1975), Roll 1, Target 3, Jan. 1891, 700-701.

[6] Kent and Baldwin, RIBWKC, 700-701.

[7] Walter R. Crickett, “Letter written at Wounded Knee,” American Museum and Gardens [https://americanmuseum.org/object/letter-written-at-wounded-knee/] accessed 12 Sep 2020, page 6.

[8] Adjutant General’s Office, Medal of Honor, Principal Record Division, file 3466, Record Group: 94, Stack area: 8W3, Row: 7, Compartment 30, Shelf: 2.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] National Library of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland, Microfilm Number: Microfilm 09200 / 07, Ireland, Catholic Parish Registers, 1655-1915 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2016); Ancestry.com and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1880 United States Federal Census (Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2010), Year: 1880, Census Place: Fort Abraham Lincoln, Burleigh, Dakota Territory, Roll: 111, Page: 197B, Enumeration District: 081; Ancestry.com, Australia, Death Index, 1787-1985 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010).

[15] “Orders, Decorations and Medals (1 December 2010), Lot 716, Quarter-Master John Nowlan, 62nd Foot, late 11th Foot,” DNW [https://www.dnw.co.uk/auction-archive/past-catalogues/lot.php?auction_id=188&lot_uid=194033] accessed 12 Sep 2020; Robert Montgomery Martin, Statistics of the Colonies of the British Empire in the West Indies, South America, North America, Asia, Australia-Asia, Africa, and Europe (London: Wm. H. Allen and Co., 1839), 597; Ancestry.com, UK, British Army Muster Books and Pay Lists, 1812-1817 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc, 2015), The National Archives of the UK, Kew, Surrey, England, General Muster Books and Pay Lists, Class: WO 12, Piece: 2851; Colburn’s United Service Magazine and Naval and Military Journal, vol. 1 (London: Hurst and Blackett, Publishers, 1857), 315; Ancestry.com, Ireland, Select Marriages, 1619-1898 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014), FHL Film Number: 101484, Reference ID: 584; Ancestry.com, Ireland, Select Deaths, 1864-1870 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014);The National Archives of Ireland, Calendars of Wills and Administrations 1858 – 1920, Administrations, 1866, page 169; Ancestry.com, Web: Ireland, Calendar of Wills and Administrations, 1858-1920 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2016).

[16] Geoff Topliss, email to Sam Russell, “Subject: Nowlan-Sandhurst records,” dtd 22 Mar 2013, with attachment of record. A copy of this record can also be obtained from The Sandhurst Collection, Royal Military College (RMC) Cadet Register, vol. 1 (1806 – 1864) War Office 151, Page 200.

[17] Ibid. The register shows that when Nowlan began his cadetship on January 21, 1851, he was 14 years and 7 months old, putting his year of birth in 1836; D. A. N. Lomax, A History of the Services of the 41st (The Welch) Regiment, (Now 1st Battalion the Welch Regiment,) from its Formation, in 1719, to 1895 (Devonport: Hiorns & Miller, 1899), 209-210.

[18] Ibid., 210-211; Ancestry.com, UK, Military Campaign Medal and Award Rolls, 1793-1949 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010), National Archives of the UK, Kew, Surrey, England, Class: WO 100; Piece: 31; Class: WO 100; Piece: 30; Class: WO 100; Piece: 29; Ancestry.com, UK, Officer Service Records, 1764-1932 (Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2019), The National Archives, Kew, London, England, WO 76 – War Office: Records of Officers’ Services; Reference: WO 76/239; James Donovan, A Terrible Glory: Custer and the Little Bighorn, the Last Great Battle of the American West (New York: Back Bay Books, 2008), 178. Donovan is one historian who states that, “Nowlan had been decorated for gallantry at the siege of Sebastopol.” Neither of Nowlan’s medals were awarded for gallantry. To qualify for the British Crimean War medal it was not enough to be present with one’s unit in the Crimea. One had to be documented by their unit as having taken part in one of the four battles—Alma, Balaclava, Inkerman, or Azoff—or during the year long siege have taken part in one of the assaults. As an example, Henry Nowlan’s father and brother were both on rolls crediting them with Alma and Inkerman. Despite being with their units in the Crimea when Balaclava occurred, neither unit participated and thus those officers did not receive a clasp for that battle. In Henry Nowlan’s case, he was not present for the battles of Alma, Balaclava, and Inkerman, but did participate in the June assault on the Great Redan, thus qualifying him for the Sebastopol clasp. However, there is conflicting information in Nowlan’s British service records. The first page of his statement of services reads, “Was present at the attack on the Redan, 18 June 1855.” The second page states, “Medal for Crimea and clasp for ‘Sebastopol’.” However the same document lists his service abroad dates in the Crimea from “29 Jan ’55 to 16 Jun 1855,” indicating that he left just prior to the battle. Additionally, his name is listed on a UK Medals roster for the 41st Foot showing officers and soldiers entitled to wear a clasp for the fall of Sebastopol, an event that occurred on September 9, 1855, after Nowlan had departed according to his service statement.

[19] Edward H. Nolan, “Capture of the Malakoff Tower,” The Illustrated History of the War Against Russia, vol. II (London: James S. Virtue, 1857), 466.

[20] Lomax, A History of the Services of the 41st Regiment, 247.

[21] The National Archives, Kew, London, England, WO 76 – War Office: Records of Officers’ Services; Reference: WO 76/239; Geoff Topliss, email to Sam Russell, “Subject: Nowlan-my article,” dtd 22 Mar 2013, with attachment of essay. In an unpublished essay, British researcher Geoff Topliss recorded the following regarding Nowlan selling his commission. “As the story goes, he had grown frustrated with his inability to progress up the ranks because he lacked the funds to purchase a captaincy. He thus ‘sold his commission’, on May 27th 1862. In fact he couldn’t have sold it. [The fact that Nowlan ‘sold up’ has long been the established line-see Williams, Military Registers, p-234.] A Lieutenant who’d received a free commission had to serve for 15 years before he could sell it. Nowlan had served for less than eight years in May 1862. What he could and probably did do, was to use the provision for non-purchase officers, with between 3 and 20 years service, to retire and receive a one off cash payment of £100 per year for each year of foreign service, and £50 per year for years home service; in Nowlan’s case this would have come to over £525. [See Bruce, Antony, The Purchase System in the British Army (Royal Historical Society-1980) for an examination of the workings of the purchase system-the financial settlement for Nowlan may have been higher, but the exact amount of time he was in the West Indies is unknown.] That gave Nowlan more than enough money to head to the USA, where trained experienced officers were desperately wanted because of the Civil War.”

[22] Historical Data Systems, comp., U.S., Civil War Soldier Records and Profiles, 1861-1865 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2009).

[23] Henry J. Nowlan, letter to Edwin M. Stanton dtd 10 May 1866, and Hnery J. Nowlan letter to Maj. Gen. Hunter dtd 24 Oct 1866, from National Archives personnel file for Henry James Nowlan, 3714-ACP-1876*, provided as attachments in email from Lee Noyes to Sam Russell, dtd 13 Oct 2020.

[24] Historical Data Systems, comp. U.S., Civil War Soldier Records and Profiles, 1861-1865 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2009), photo courtesy of Mike Medhurst.

[25] “Capture of Five Companies of Union Cavalry,” Chicago Tribune (Chicago: 6 Jul 1863), 2.

[26] Robert N. Scott, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, series I, vol. XXVI, part 1 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1889), 50.

[27] New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center, Report of the Adjutant General Fourteenth Cavalry, page 428 [https://dmna.ny.gov/historic/reghist/civil/rosters/cavalry/14thCavCW_Roster.pdf] accessed 27 Sep 2020.

[28] Asa B. Isham, Henry M. Davidson & H. B. Furness, Prisoners of war and military prisons; personal narratives of experience in the prisons at Richmond, Danville, Macon, Andersonville, Savannah, Millen, Charleston, and Columbia with a list of officers who were prisoners of war from January 1, 1864 (Cincinnati: Lyman & Cushing, 1890), 75.

[29] Historical Data Systems, comp., U.S., Civil War Soldier Records and Profiles, 1861-1865 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2009); Isham, Davidson & Furness, Prisoners of war and military prisons, 79.

[30] Ibid., 90.

[31] L.R. Hamersly, Records of the Living Officers of the United States Army (Philadelphia: L. R. Hamersly & Co., 1884), 168; New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center, Report of the Adjutant General Eighteenth New York Cavalry, page 1267, [https://dmna.ny.gov/historic/reghist/civil/rosters/cavalry/18thCavCW_Roster.pdf] accessed 27 Sep 2020; Ibid., Report of the Adjutant General Fourteenth Cavalry, page 428 [https://dmna.ny.gov/historic/reghist/civil/rosters/cavalry/14thCavCW_Roster.pdf] accessed 27 Sep 2020; Henry J. Nowlan, letter to Edwin M. Stanton dtd 10 May 1866, and Hnery J. Nowlan letter to Maj. Gen. Hunter dtd 24 Oct 1866. Regarding when Nowlan escaped from prison, he wrote to Secretary Stanton that “I remained in the hands of the enemy till February 1865, when I succeeded in making my escape from Columbia, S.C.” He later wrote to Maj. Gen. Hunter “I was captured and remained a prisoner till March 1865, when I escaped.” Regarding Nowlan’s promotion to captain during the Civil War, the records do not agree. The entry for “Nolan, Henry J.” in the 14th N.Y. Cav., Regiment roster states, “commissioned captain, August 10, 1863, with rank from February 7, 1863.” The 18th N.Y. Cav. roster states, “mustered in as captain, Co. K, January 14, 1866.” The Official Army Register records that Nowlan was promoted to Captain in the 14th N.Y. Cav. on October 24, 1864. Williams in Military Register of Custer’s Last Command records that he was promoted to Captain January 24, 1866. Memorials of Deceased Companions uses the October 24, 1864 date from the Official Army Register. I have chosen to use the dates recorded in the 14th N.Y. Cav. roster, but certainly Nowlan would have been aware of and, at least tacitly, agreed with the October 24, 1864, date.

[32] “Two Men Killed and Three Wounded,” New Orleans Crescent (New Orleans: 24 Apr 1866), 2; “Fight in Texas.” Chicago Tribune (Chicago: 31 Mar 1866), 1. In the several newspaper accounts and official records, Nowlan’s name was spelled variously as Nowlan, Nolan, Nolen, and Noolan.

[33] James Shaw Jr, letter dtd 19 Mar 1866, Collins Chesbrough, letter dtd 26 Mar 1866, William Davis, letter dtd 29 Mar 1866, Davis, letter dtd 24 Apr 1866, “Removal of the Hon. E. M. Stanton and Others,” Executive Documents Printed by Order of The House of Representatives during the Second Session of the Fortieth Congress, 1866-’67, vol. vii (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1868), 95, 107 & 109.

[34] Roger L. Williams, Military Register of Custer’s Last Command (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2012), 234.

[35] David F. Barry, “Captain Henry J. Nowlan, standing, in uniform & hat, 3/4 length,” Denver Public Library Digital Collections, [https://digital.denverlibrary.org/digital/collection/p15330coll22/id/68670/rec/1] accessed 16 Sep 2020.

[36] Williams, Military Register of Custer’s Last Command, 176-177; Elizabeth A. Lawrence, His Very Silence Speaks: Commanche–The Horse Who Survived Custer’s Last Stand (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1989), 87.

[37] Williams, Military Register of Custer’s Last Command, 234.

[38] Henry J. Nowlan, Letters Received by the Adjutant General, 1871-1880, NARA M666. Unbound letters, with their enclosures, received by the Adjutant General, 1871-1880, [https://www.fold3.com/image/298434958] accessed 13 Sep 2020.

[39] Williams, Military Register of Custer’s Last Command, 234; Lawrence, His Very Silence Speaks, 87, 97 & 98.

[40] Adjutant General’s Office, Official Army Register for January 1877 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1877), 66.

[41] Forty-Fifth Congress, Report of the Secretary of War; Being part of the Messages and Documents Communicated to the Two Houses of Congress Beginning of the Second Session of the Forty-Fifth Congress, vol. 1 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1877), 544. The Secretary of War’s report includes the following entries regarding the expedition to recover the 7th Cavalry officers’ remains:

June 20, 1877.–About 7 o’clock Company I, Seventh Cavalry (Captain Nowlan), reached the north bank of the Yellowstone, having been detached as escort of Colonel Sheridan, who was to proceed to the Little Bighorn for the purpose of securing the bodies of the officers who fell in the Custer fight. Later in the day Colonel Sheridan passed up the river on the steamer Fletcher….

June 21, 1877.–Captain Nowlan continued on his march to the Little Bighorn to meet Colonel Sheridan at that point….

July 8, 1877.–The steamer Fletcher arrived to-day from the Bighorn River, having on board Colonel Sheridan, of Lieutenant-General Sheridan’s staff, in charge of the bodies of General Custer and 9 other officers killed in the fight on the Little Bighorn June 25, 1876.

July 13, 1877.–Company I, Seventh Cavalry (Captain Nowlan), returned from escorting Colonel Sheridan in the Little Bighorn country, going into camp on the north bank of the Yellowstone.

[42] Ibid., 571; Adjutant General’s Office, Official Army Register January 1894 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1894), 295, 296, 317, 319, 325, and 330.

[43] Lewis Merrill, “Merrill’s and Benteen’s Battalions, Seventh Cavalry, in the Battle of Cañon Creek, Mont., September 13, 1877,” Report of the Secretary of War, 569-571. Captain Nowlan commended ten men of his company for their actions: First Sergeant Murphy, Sergeant Costello, Corporal Culbertson, Privates George Smith, H. Williams, Korn, Mayer, Miles, Thresh, and Crowley. He had two men wounded in the fight: Private E. B. Crowley and Farrier Rivers (slightly). In addition to Nowlan, Lt. Col. L. Merrill, Maj. F. W. Benteen, Capts. C. Bendire, J. M. Bell, and Lieuts. R. H. Fletcher, E. B. Fuller, H. J. Slocum also were awarded brevet promotions for their conduct at Canyon Creek.

[44] National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Washington, D.C., Soundex Index to Naturalization Petitions for the United States District and Circuit Courts, Northern District of Illinois and Immigration and Naturalization Service District 9, 1840-1950, Microfilm Serial: M1285, Microfilm Roll: 130; NARA, Washington, D.C., Returns from U.S. Military Posts, 1800-1916, Microfilm Serial: M617, Microfilm Roll: 1014.

[45] Lawrence, His Very Silence Speaks, 111; Edward S. Godfrey, General George A. Custer and the Battle of the Little Big Horn (New York: The Century Co., 1908), 38.

[46] Williams, Military Register of Custer’s Last Command, 234; NARA, Washington, D.C., Returns from U.S. Military Posts, 1800-1916, Microfilm Serial: M617, Microfilm Roll: 1092;

[47] “Promotions Caused by Lieutenant Colonel Purington’s Retirement,” The Daily Inter Ocean (Chicago: 20 Jul 1895), 6.

[48] Williams, Military Register of Custer’s Last Command, 234; Ancestry.com, U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012), Image: 375; “Military Funeral,” Arkansas Democrat (Little Rock: 11 Nov 1898), 2.

[49] Ancestry.com, Little Rock, Arkansas, Little Rock National Cemetery, 1868-2010 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011), Little Rock National Cemetery; Section: 11.

[50] Ancestry.com, Washington, D.C., Wills and Probate Records, 1737-1952 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015), Probate Records (District of Columbia), 1801-1930, Case Number: 9108; Item Description: Wills, Boxes 0184 Gorham – 0188 Wells, 1899; “In the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia,” Evening Star (Washington: 6 Oct 1899), 4; “Contests Her Uncle’s Will,” Washington Times (Washington: 30 Apr 1901), 4; PGK, “Maude Nowlan,” FindAGrave (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/199437062/maude-nowlan), posted 25 May 2019, accessed 3 Oct 2020, “Maude daughter of the late Colonel John Nowlan died 18th Sept 1920 aged 54”; Ancestry.com, England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1858-1995 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010), Name: Thomas Bowman Nowlan; Death Date: 8 Jan 1929; Death Place: Somerset, England; Probate Date: 5 Feb 1929; Probate Registry: London, England.

Citation for this article: Samuel L. Russell, “Captain Henry James Nowlan, Commander, I Troop 7th Cavalry—Gallant Service,” Army at Wounded Knee, (Carlisle, PA: Russell Martial Research, 2020, https://wp.me/p3NoJy-1GN) posted 4 Oct 2020, accessed date __________.

I posted a comment with my email address. Your computer kept asking for the address and need forwarded it. I asked if you researched the man who treated the wounded at the mission after the massacre, The book Oniashu (sp?) mentions a woman in the ravine and a man on horseback who came up to the ravine, emptied his gukker into the women, laughed, and rode away.

>

LikeLike

Cheryl… Thank you for your comment. I am unable to determine the source that you reference in your comment. Can you be more specific?

LikeLike

Great research. Enjoyed all the background on Nowlan.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sam– Great report on Nowlan, and I learned a lot! Keep up your wonderful research on WK.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Update 1: This post was updated on October 5, 2020, to insert analysis of the 14th N.Y. Cav. Regt. Roster detailing the number of soldiers reported captured near Port Hudson on June 15, 1863. It is the paragraph annotated with footnote [26] (now footnote [27]).

Update 2: This post was updated on October 16, 2020, to insert the date that Nowlan was captured (June 18, 1863) and the date that he was wounded (March 8, 1866) according to a letter that he wrote to the Secretary of War on May 10, 1866, requesting an appointment in the Regular Army. The footnotes were updated and renumbered accordingly.

LikeLike

Congratulations, Sam, on another outstanding 7th Cavalry profile that reflects your usual exhaustive research based on original and other primary sources. You certainly do justice to the captain!

While researching at the National Archives in the 1990s I had the opportunity to review briefly his ACP file and to make a few copies, including the attached PDF documents, which might be of interest. They verify that Nowlan escaped from Confederate custody at Columbus, SC but provided conflicting 1865 dates as your column states.

We plan to forward your message to our email network.

Best Regards,

Lee

Attachments:

1. Henry J. Nowlan ACP Fie NARA.pdf

2. Henry J. Nowlan application May 10, 1866 ACP file.pdf (2 pages)

3. Henry J. Nowlan statement Oct. 24, 1866 ACP file.pdf (3 pages)

LikeLiked by 1 person