Several of these Indians were wounded, and I had my dressers care for the wounds dressing a child’s wound myself.

Captain Winfield S. Edgerly, Commander, G Troop, 7th Cavalry, at Pine Ridge Agency, 16 January 1891. Cropped from John C. H. Grabill’s photograph, “The Fighting 7th Officers.”

Captain Winfield Scott Edgerly was forty-four years old at Wounded Knee. He joined the 7th cavalry two decades earlier after graduating from West Point in June 1870. As the second lieutenant of D Company, Edgerly fought in Captain Benteen’s battalion at the Battle of Little Big Horn. Edgerly was appointed the captain of G troop in 1883 while on recruiting service and joined his new troop in the fall of 1884 commanding it since that time. He had with him at Wounded Knee his first lieutenant, Edwin P. Brewer, but his second lieutenant, J. Franklin Bell, had not yet rejoined the troop by the end of December. Edgerly’s first sergeant was twenty-five-year-old Frederick E. Toy, a New York native two years into his second enlistment. G Troop had four of its five sergeants present and four corporals. His troop served as part of the regiment’s 2nd Battalion, then commanded by Captain Charles Ilsley, and formed up mounted on the eastern side of the cavalry camp at Wounded Knee the morning of December 29th.

Writing to his wife at Fort Riley on the evening of December 29 after returning from Wounded Knee, Capt. Edgerly described his and his units actions that day.

Pine Ridge S. D.

Pine Ridge S. D.

Dec. 29, 1890. 10 55 P.M.

My Darling Wife:

I shall give up predicting about Indians when they are Ghost dancers after today’s work.

Brewer and I sat on our horses in front of the tents and watched the surrounding and disarming of those and said “The jig is up and this means Riley for us in a week or two.” I never felt much surer of anything in my life than that we would have no fight until a couple of Indians commenced dancing the ghost dance and then all at once one of them commenced tossing dust in the air and I said “It has come” and before I could dismount my Troops a terrific battle was going on. I had the horses put in a ravine and the men in skirmish line in about a minute and they behaved beautifully and shot to kill. I didn’t see a single case of lack of bravery and saw several Indians bite the dust from G. Troop bullets. As soon as the heavy firing was over I was ordered to go after the escaped Indians and when I was about a mile or two from camp and we has just captured nineteen men women and children I first heard of poor Wallace’s death and Garlington’s wound. I didn’t hear of Hawthorne’s wound until after I got back to camp. Garlington is hit in the right elbow and Hawthorne in the groin. We don’t know yet how serious either of them is but just as soon as I find out I will let you know.

Everybody behaved beautifully as far as I saw or have heard and the 7th needn’t be ashamed of today’s record. I have been thinking of Mrs. Wallace a great deal today and pity her from the bottom of my heart. Give her my love and tell her I will write her about the noble way her gallant husband died. We didn’t have a man scratched in G Troop altho’ we had two horses killed and holes shot in our guidon and the men’s clothing. Serg’t Campbell rec’d a bad wound in the face and I understand tonight that twenty five of our people were killed outright and three of the wounded died on their way in here. The Indians lost more than one hundred bucks and a great many squaws and papooses.

I found Jackson and Donaldson at the end of a ravine, where I went after runaway Indians as I told you, and they had the nineteen Indians corralled. Lieut. Taylor with his scouts was under my command and thro’ his interpreter we got them to surrender after they had killed one of Jackson’s men, Defreide. A spent bullet hit Donaldson’s belt and he has the bullet and Doctor Hoff was hit in the belt twice but not hurt. When the report of our fight got here the Indians here were very much excited and a large number of them including some of Little Wound’s and Two Strike’s bands left, presumably for the bad lands.

I am afraid that means a Winter campaign for us and only this morning I felt so sure of a speedy and happy home coming. Nowlan came in while I was writing the above and just left it is now 12.40 and I must get some sleep. Good bye. God bless us all together and bring us happily together very soon. I thank Him for my preservation and for you.

With love to all my friends I remain

Your Loving and Devoted Husband,W. S. Edgerly

Captain 7th Cavalry

Good Love Kiss.Dec. 30. Morning. Boots and saddles have sounded again. They say the 9th Cav’y wagon train has been attacked

Your Loving Husband

Winfield [1]

Captain Edgerly concisely recorded his unit’s actions at Wounded Knee and the mission fight in his December muster roll and casually mentioned “exterminating” Big Foot’s band.

Marched from Pine Ridge Agency, S.D., to Wounded Knee Creek, S.D., Dec. 28th, ‘90, distance 17 miles. Participated in disarming and exterminating the Sioux Indians under Chief Big Foot. 2 horses killed and one wounded. Dec. 29th, ‘90, marched from Wounded Knee Creek to Pine Ridge Agency, S.D., distance 17 miles. Dec. 30th, 1890, participated in the engagement with Hostile Sioux Indians under Chief “Two Strike” six miles north of Pine Ridge Agency, S.D. Private Francischetti killed in action. 1 Horse wounded.[2]

It was Captain Edgerly’s firm belief that Private Franceschetti was killed on 30 December, but the troop commander made no mention that the private’s body was left on the battlefield. Edgerly was called to testify in the Wounded Knee investigation on 9 January 1891 at the second battalion’s camp on a branch of White Clay Creek where he expounded on the actions of this troop.

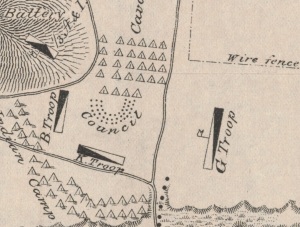

(Click to enlarge) Inset of Lieut. S. A. Cloman’s map of Wounded Knee depicting the scene of the fight with Big Foot’s Band, December 29, 1890.

I commanded Troop G, 7th Cavalry, during the engagement of the Wounded Knee on the 29th of December, 1890, and my Troop is approximately correctly located on the map (appended). My Troop was not endangered in its position from the fire of the other Troops. I had no men wounded there.[3]

Captain Edgerly’s testimony on whether or not his troop was endangered by friendly fire–and he was emphatic that they were not–was critical, as the map clearly showed his troop positioned across from and facing Captain Varnum’s B Troop.

Very shortly after the heavy firing commenced I received an order from General Forsyth, through the Regimental Adjutant, to move off in pursuit of the escaped Indians. I also had Lieut. Taylor, with some scouts, and soon after we got away from the camp we saw a little bundle on the side of the hill, which I took to be a baby, and I sent a scout, cautioning the men not to shoot, and the scouts took it in. I saw no more live Indians within carbine range until I got to the head of the ravine, which ran back of the tepees. There I found Captain Jackson with his Troop, who had corralled some Indians. They were firing on the Indians, who answered the fire and had just killed one of his men. I found that the Indians had dug under an overhanging bank and were entirely covered from sight. Then Lieut. Taylor reported to me that he had a scout who had relatives amongst that crowd, and he thought if we promised not to kill them that they could be induced to surrender. I spoke to Captain Jackson, and he gave permission for this offer to be made, which was done, he drawing off with his command a little distance. They tried to make a condition that the soldiers we had in line should be drawn further back. This was refused, but they were assured that they would not be killed if they would surrender. One or two were so badly wounded they had to be brought out, and the rest, making in all 23, walked up to where we were. We took two belts of ammunition off the persons of the squaws. There were 7 bucks in the party, and they had left 9 rifles in the ravine, which we took. Several of these Indians were wounded, and I had my dressers care for the wounds dressing a child’s wound myself. I don’t know that my men fired at a squaw. I had no occasion to caution my men. I saw no squaws within rifle range and saw no men firing at them after the first heavy fire; neither did they fire at them then.[4]

One of the two investigators then asked, “Under all the circumstances attached to the work of the day in question, do you consider that the disposition made of all the troops was judicious before the opening of the engagement?” to which Captain Edgerly responded:

It seemed to me that those troops situated to the south across the ravine, were in danger in case of the firing that took place from our troops, which I did not, however anticipate. I thought it was good as a display of force to prevent their attempting to escape. No human beings, I thought, would attempt a fight under such circumstances. I think it was simply a display of troops with a view to overawe the Indians, and that nothing but fanaticism would have induced an attempt to resistance. I wish to say that we were not in much danger where located as described; we could have been hit from the fire of our men had they aimed at running Indians coming towards us.[5]

Following the campaign toward the end of March, Captain Edgerly recommended four of his troopers be awarded Medals of Honor for actions in the Wounded Knee and Drexel Mission fights. Where Edgerly had testified that his troop was not in danger from the small arms fire during the opening of the fight, his narrative in one of the award recommendations indicated that his troop did indeed take fire.

At the time the firing at Wounded Knee commenced, my troop was mounted and near the Indians. I immediately dismounted it and ordered the horses to be taken to the ravine close by, for cover. Bullets whistled over our heads, two horses were hit and they were all more or less frightened. The pack mule carrying extra ammunition and several of the horses stampeded and ran away in the direction in which the bullets were flying.[6]

Later that fall during Colonel Edward M. Heyl’s investigation into acts of heroism, gallantry, and fortitude, Captain Edgerly was asked to state if he had “observed any acts of conspicuous gallantry or heroism on the part of officers or enlisted men during the engagements at Wounded Knee and Drexel Mission,” to which he answered:

There were no conspicuous acts of gallantry or heroism that I observed. I noticed several officers under fire who behaved with coolness and bravery, but their acts were not specially conspicuous. They were Nowlan, Lieut. Gresham and Lieut. Brewer.

I did not observe Major Whitside.

I saw Captains Ilsley and Godfrey and Lieut. Donaldson; they all behaved well throughout the day as far as I saw them.

I also wish to metion [sic] Dr. Glennan; he was cool and acted nobly at both Wounded Knee and the Mission fights.

Four men received medals: Sergeant E. Hennesse, Private F. Mahoney, 1st Sergeant F. E. Fog [sic: Toy] and Private M. H. Hamilton.[7]

Colonel Heyl was mistaken in that only two men from Captain Edgerly’s troop, Toy and Hamilton, were awarded Medals of Honor. The other two mentioned, Hennessee and Mahoney, were recommended by Edgerly for medals for actions at White Clay Creek, but Major General John M. Schofield approved the recommendations for honorable mention only. Also during the course of Colonel Heyl’s investigation, Lieutenant Brewer testified that he thought Captain Edgerly’s conduct at Wounded Knee was conspicuous. This led the Adjutant General’s Office to prepare a citation for honorable mention in general orders, but General Schofield ruled out the citation from the order, his Adjutant General stating, “Maj. Genl. Schofield will not take up cases of gallantry and good conduct, for honorable mention in orders, referred to by various officers in their testimony taken by Col. Heyl, and embodied in his report of Oct. 27, 1891, but not recommended by Col. Heyl or General Miles, or other Department Commanders.”[8]

Winfield Scott Edgerly was born on 29 May 1846 at Farmington, New Hampshire, the sixth of seven children of Josiah Bartlett and Cordelia (Waldron) Edgerly. Josiah, then in his forty-sixth year, made a living as a wheelwright, a farmer, and a carpenter according to census takers, but he also served as a state commissioner and a state justice for the county of Strafford and was addressed as the Honorable Josiah B. Edgerly. Additionally, Josiah served as an Auxiliary for the Strafford County Temperance Society. Born and raised in Strafford, Josiah met and married Cordelia Waldron there in 1833. She was the twenty-two year old daughter and the sixth of twelve children of Jeremiah and Mary (Scott) Waldron. Cordelia bore Josiah seven children: James Bartlett, born in 1834, was a prominent New Hampshire banker and died in 1922; Eliza Waldron, born in 1835, died a few weeks after her second birthday; Henry Irving, born in 1838, was a shoemaker and died in 1923; George Prentiss, born in 1840, was a student when he died of scrofula in 1864; Cordelia Augusta, born in 1844, became Mrs. Thomas F. Cooke and was last of the Edgerly children still living before she died in 1932; Winfield Scott, born in 1846, is the subject of this post; and Mary was born in 1849 and died before her first birthday. Mrs. Cordelia Edgerly died in 1854 at the age of forty-three. Josiah married Eliza Jane Hayes in 1856, and she bore him one daughter, Mary Alice, a year later. Eliza died in 1877 and Josiah in 1888.[9]

Growing up in Farmington, Winfield S. Edgerly attended school in that town before furthering his education at the Effingham Institute and Phillips-Exeter Academy. He was appointed to the United States Military Academy from the state of New Hampshire and entered West Point in 1866. Edgerly graduated forty-ninth in a class of fifty-seven and was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the 7th Cavalry, where he joined Captain Tom Weir’s black horse D Troop in 1870.[10]

Growing up in Farmington, Winfield S. Edgerly attended school in that town before furthering his education at the Effingham Institute and Phillips-Exeter Academy. He was appointed to the United States Military Academy from the state of New Hampshire and entered West Point in 1866. Edgerly graduated forty-ninth in a class of fifty-seven and was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the 7th Cavalry, where he joined Captain Tom Weir’s black horse D Troop in 1870.[10]

With D Troop, Edgerly served briefly in Kansas at Forts Riley and Leavenworth before taking up reconstruction duties in the South at places like Mt. Vernon, Kentucky, Meridian, Mississippi, Chester, South Carolina, Opelika, Alabama, and Memphis, Tennessee. In 1873, the 7th Cavalry was assigned to the Department of Dakota and Edgerly served the summers of 1873 and 1874 escorting the Northern Boundary Survey and wintering at Fort Totten. He was eventually posted with the 7th Cavalry at Fort Abraham Lincoln in May 1875.[11]

Later that year on 27 October Edgerly married a young nineteen-year-old St. Paul, Minnesotan named Grace Corey Blum. Born on 3 October 1856 at Cooperstown, New York, she was the daughter of Louis and Nancy (Cory) Blum. Her father was a German emigrant and made a living as a merchant and a clerk. Louis moved the family from Cooperstown to St Paul in the Minnesota Territory when Grace was an infant where he had established a dry goods business selling fashionable and costly items. St Paul was the only home Grace knew until her dashing six-foot-tall cavalry officer took her to the Dakota Territory. Married just eight months when catastrophe befell the regiment at the Little Big Horn, Edgerly wrote his wife from the Yellowstone Depot July 4th providing details of the battle in a well published letter. He tried to comfort her–and perhaps himself–by closing with, “Now, my precious, I must kiss you goodbye. I wish I could really hold you in my arms and kiss you now.” Thier marriage produced one child, Winifred, born in July 1881 in the Datkota Territory, but the girl died three and a half years later at Fort Leavenworth where the Edgerly’s had her buried.[12]

Later that year on 27 October Edgerly married a young nineteen-year-old St. Paul, Minnesotan named Grace Corey Blum. Born on 3 October 1856 at Cooperstown, New York, she was the daughter of Louis and Nancy (Cory) Blum. Her father was a German emigrant and made a living as a merchant and a clerk. Louis moved the family from Cooperstown to St Paul in the Minnesota Territory when Grace was an infant where he had established a dry goods business selling fashionable and costly items. St Paul was the only home Grace knew until her dashing six-foot-tall cavalry officer took her to the Dakota Territory. Married just eight months when catastrophe befell the regiment at the Little Big Horn, Edgerly wrote his wife from the Yellowstone Depot July 4th providing details of the battle in a well published letter. He tried to comfort her–and perhaps himself–by closing with, “Now, my precious, I must kiss you goodbye. I wish I could really hold you in my arms and kiss you now.” Thier marriage produced one child, Winifred, born in July 1881 in the Datkota Territory, but the girl died three and a half years later at Fort Leavenworth where the Edgerly’s had her buried.[12]

Edgerly continued assignment with the 7th Cavalry regiment for most of his career. In the later half of the 1890s he served as an instructor in Maine at State College and as an instructor of the National Guard in his native state at Concord. During the war with Spain he was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in the U.S. Volunteers and served as an inspector general at various state-side postings. Promotions came quickly during the war, and Edgerly was promoted Major in the 6th Cavalry in the summer of 1898 but never joined that regiment. He reverted to his regular rank the following spring after being discharged from the Volunteers and transferred back to the 7th Cavalry, which he joined on occupation duty in Havana, Cuba in 1899. While still serving in Cuba Edgerly was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in 1901 in the 10th Cavalry and was again transferred back the his old regiment the following month. He returned to duty in the U.S. serving briefly at Chickamauga Park. Edgerly was promoted to Colonel of the 12th Cavalry in 1903 taking command of that regiment at Fort Myer, Virginia, before deploying to the Philippines where he served for eighteen months commanding Camp Wallace de Union and Camp Stotsenburg.[13]

Edgerly continued assignment with the 7th Cavalry regiment for most of his career. In the later half of the 1890s he served as an instructor in Maine at State College and as an instructor of the National Guard in his native state at Concord. During the war with Spain he was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in the U.S. Volunteers and served as an inspector general at various state-side postings. Promotions came quickly during the war, and Edgerly was promoted Major in the 6th Cavalry in the summer of 1898 but never joined that regiment. He reverted to his regular rank the following spring after being discharged from the Volunteers and transferred back to the 7th Cavalry, which he joined on occupation duty in Havana, Cuba in 1899. While still serving in Cuba Edgerly was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in 1901 in the 10th Cavalry and was again transferred back the his old regiment the following month. He returned to duty in the U.S. serving briefly at Chickamauga Park. Edgerly was promoted to Colonel of the 12th Cavalry in 1903 taking command of that regiment at Fort Myer, Virginia, before deploying to the Philippines where he served for eighteen months commanding Camp Wallace de Union and Camp Stotsenburg.[13]

(Click to enlarge) President Roosevelt greeting Lieut-Colonel Edgerly of the 7th U.S. Cavalry, Chickamauga, Tenn. (Washington: Underwood & Underwood, 1902).

Edgerly was promoted to Brigadier General in the summer of 1905 and took command of the Department of Luzon and later Fort William McKinley. He returned to the U.S. in January 1907 to take command of the Department of the Gulf. That summer he and Gracie traveled to Germany where Edgerly was a guest of the emperor and served as an official observer of the Kaiser maneuvers. The Edgerly’s returned to Washington, D.C., for six months when in May 1908 they returned to Mrs. Edgerly’s hometown of St Paul where he took command of the Department of Dakota. In the summer of 1909 Edgerly was assigned to command Fort Riley and the Cavalry and Artillery School. He was less than a year from mandatory retirement at age sixty-four and was on a short list to be promoted to Major General but was ailing badly. Edgerly had suffered from chronic cystitis in 1899 in Cuba and again in the Philippines. Eventually, the symptoms of swollen testicles coupled with an enlarged prostate precluded the cavalry general from riding a horse. In July he was ordered before a medical board where the examiners pronounced that the debilitating disease was permanent in a man his age and incapacitated him for active service. General Edgerly was medically retired in December 1909 at the age of sixty-three.[14]

Edgerly was promoted to Brigadier General in the summer of 1905 and took command of the Department of Luzon and later Fort William McKinley. He returned to the U.S. in January 1907 to take command of the Department of the Gulf. That summer he and Gracie traveled to Germany where Edgerly was a guest of the emperor and served as an official observer of the Kaiser maneuvers. The Edgerly’s returned to Washington, D.C., for six months when in May 1908 they returned to Mrs. Edgerly’s hometown of St Paul where he took command of the Department of Dakota. In the summer of 1909 Edgerly was assigned to command Fort Riley and the Cavalry and Artillery School. He was less than a year from mandatory retirement at age sixty-four and was on a short list to be promoted to Major General but was ailing badly. Edgerly had suffered from chronic cystitis in 1899 in Cuba and again in the Philippines. Eventually, the symptoms of swollen testicles coupled with an enlarged prostate precluded the cavalry general from riding a horse. In July he was ordered before a medical board where the examiners pronounced that the debilitating disease was permanent in a man his age and incapacitated him for active service. General Edgerly was medically retired in December 1909 at the age of sixty-three.[14]

In retirement, the Edgerly’s lived in Ostego, New York, and Dover, New Hampshire. General Edgerly was called back to active service briefly for two months in the summer of 1917 as a member of the Military Emergency Board in New Hampshire and commanded Mobilization Camp Concord. He lived for another decade and passed away on 10 September 1927 at his home in Farmington, New Hampshire, the town of his birth. Brigadier General Winfield Scott Edgerly was laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery. Gracie Edgerly joined her husband in death twelve years later and was buried by his side.[15]

Brigadier General Winfield Scott Edgerly and his wife, Grace, nee Blume, are buried in Arlington National Cemetery.[16]

Endnotes:

[1] Winfield S. Edgerly, letter to Mrs. W. S. Edgerly, dtd 29 Dec 1890, from “Wounded Knee Massacre Same Day Eyewitness Account by,” LiveAuctioneers [https://www.liveauctioneers.com/item/81343069_wounded-knee-massacre-same-day-eyewitness-account-by], posted 26 Feb 2020, accessed 16 Sep 2020.

[2] Adjutant General’s Officer, “7th Cavalry, Troop G, Jan. 1885 – Dec. 1897,” Muster Rolls of Regular Army Organizations, 1784 – Oct. 31, 1912, Record Group 94, (Washington: National Archives Record Administration).

[3] Jacob F. Kent and Frank D. Baldwin, “Report of Investigation into the Battle at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota, Fought December 29th 1890,” in Reports and Correspondence Related to the Army Investigations of the Battle at Wounded Knee and to the Sioux Campaign of 1890–1891, the National Archives Microfilm Publications (Washington: The National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration, 1975), Roll 1, Target 3, Jan. 1891, 37-40.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Adjutant General’s Office, Medal of Honor file for Matthew H. Hamilton, Principal Record Division, file 3466, Record Group: 94, Stack area: 8W3, Row: 7, Compartment 30, Shelf: 2. Research conducted by Vonnie S. Zullo of The Horse Soldier Research Service.

[7] Adjutant General’s Office, Case of Honorable Mention for Winfield S. Edgerly, Principal Record Division, file 3466, Record Group: 94, Stack area: 8W3, Row: 7, Compartment 30, Shelf: 2. Research conducted by Vonnie S. Zullo of The Horse Soldier Research Service.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ancestry.com, United States Federal Census (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009), Year: 1850; Census Place: Farmington, Strafford, New Hampshire; Roll: M432_440; Page: 311A; Image: 246; Year: 1860, Census Place: Farmington, Strafford, New Hampshire, Roll: M653_680, Page: 432, Image: 436, Family History Library Film: 803680; Year: 1870, Census Place: Farmington, Strafford, New Hampshire, Roll: M593_849, Page: 177B, Image: 365, Family History Library Film: 552348; Year: 1880, Census Place: Farmington, Strafford, New Hampshire, Roll: 769, Family History Film: 1254769, Page: 173C, Enumeration District: 249, Image: 0346; Ancestry,com, New Hampshire, Marriage and Divorce Records, 1659-1947 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2013); The New Hampshire Annual Register and United States Calendar, vol. 46 (Concord: G. P. Lyon, 1866), 24 and 46; Fifth Annual Report of the New Hampshire Temperance Society (Concord: Statesman Office–M’Farland and Ela, Printers, 1833), 16; Ancestry.com, U.S., Newspaper Extractions from the Northeast, 1704-1930 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014), Newspaper: Boston Transcript, Publication Date: 10 Apr 1888, Publication Place: Massachusetts, Call Number: 486680.

[10] Henry B. F. MacFarland, District of Columbia: Concise Biographies of its Prominent and Representative Contemporary Citizens, and Valuable Statistical Data, 1908-1908 (Washington: The Potomac Press Publishers, 1908), 139; Ernest A. Garlington, “Winfield Scott Edgerly,” Sixty-Second Annual Report of the Association of Graduates of the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York (Chicago: The Lakeside Press, 1931), 93.

[11] George W. Cullum, Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, since its establishment in 1802, vol. 3, 163.

[12] Ancestry.com, United States Federal Census, Year: 1860, Census Place: St Paul, Ramsey, Minnesota, Roll: M653_573, Page: 97, Image: 101, Family History Library Film: 803573; Year: 1870, Census Place: St Paul Ward 5, Ramsey, Minnesota, Roll: T132_10, Page: 1406, Image: 210, Family History Library Film: 830430; Ancestry.com, Minnesota, Territorial and State Censuses, 1849-1905 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007), Census Date: 21 Sep 1857, County: Ramsey, Locality: St Paul, Line: 39, Roll: MN1857_4; Census Date: 1 May 1875, County: Ramsey, Locality: St Paul Ward 5, Line: 18, Roll: MNSC_14; Ancestry.com, Minnesota, Marriages Index, 1849-1950 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011), FHL Film Number: 1314548; Thomas M. Newsome, Pen Pictures of St Paul, Minnesota, and Biographical Sketches of Old Settlers from the Earliest Settlement of the City, up to and Including the Year 1857, vol. 1 (St Paul: Thomas M. Newsome, 1886), 722; Gordon C. Harper, The Fights on the Little Horn Companion: Gordon Harper’s Full Appendices and Bibliography (Havertown, PA: Casemate Publishers, 2014), 2.10; Ancestry.com, U.S., Burial Registers, Military Posts and National Cemeteries, 1862-1960 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012), Burial Place: Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, Cemetery: Fort Leavenworth National Cemetery, Grave Site: A-1879.

[13] Cullum, Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the United States Military Academy, vol. 4, 203, and vol. 5, 175; Garlington, “Winfield Scott Edgerly,” 95-96.

[14] Cullum, Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the United States Military Academy, vol. 5, 175, vol. 6, 155, and vol. 7, 102; Garlington, “Winfield Scott Edgerly,” 96; Fold3.com, “Edgerly, Winfield S.,” Letters Received by the Appointment, Commission and Personal Branch, Adjutant General’s Office, 1871-1894 (), Publication Number: M1395, Record Group: 94, Roll Name: M1395_Drum-Edgerly, Images: 459-491.

[15] Cullum, Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the United States Military Academy, vol. 7, 102; Garlington, “Winfield Scott Edgerly,” 96; Ancestry.com, U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962 (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012), Images: 528 and 534.

[16] Michael W. Patterson, photo., “Winfield Scott Edgerly,” Arlington National Cemetery Website (http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/wedgerly.htm) posted 3 Dec 2004, accessed 12 Sep 2015.

Citation for this article: Samuel L. Russell, “Captain Winfield Scott Edgerly, Commander, G Troop, 7th Cavalry,” Army at Wounded Knee, (Carlisle, PA: Russell Martial Research, 2016-2020, http://wp.me/p3NoJy-N1) updated 16 Feb 2020, accessed _______.

The officer in full dress cradling the saber is not Edgerly. It is Lt. Charles Larned, USMA class of 1870; he was a classmate of Edgerly’s. Benny Hodgson was also in that class. Larned was the son of Paymaster William Larned. He joined the regiment in Oct. 1870 assigned to Co. F. He served in the south and took part in the 1873 Yellowstone Expedition. Thereafter he was on detached duty in Washington D.C. as an aide to President Grant; then appointed as professor of drawing at the USMA. One who Benteen would surely have labeled a “coffee cooler” , Larned was promoted to 1Lt to fill Little Big Horn KIA vacancies. He stayed at West Point until resigning his commission in Sept. 1876, possibly due to medical reasons. He was not an admirer of George A. Custer; the book Custer’s Seventh Cavalry Comes to Dakota by Roger Darling provides some of insight into Larned, containing some of his letters to his mother. This is an excellent work on the 1873 transfer of the regiment from Reconstruction duty to their new assignment in Dakota Territory; the only book dealing solely with this period in the history of the regiment.

LikeLike

Outstanding. Thank you for the correction and update. I didn’t think the photograph looked like the others I have of Edgerly. I’ll remove the photograph and replace with another known to be Edgerly.

From Bill Thayer’s site detailing Charles Larned, it seems he did not resign his commission. Rather he spent almost four decades teaching at West Point:

Charles W. Larned held the rank of Colonel at the time of his death.

LikeLike

Sam, both Nichols/Hammer (Men With Custer) and Williams (Military Register of Custer’s Last Command) as well as Klokner (Officer Corp of Custer’s Seventh Cavalry) have Larned resigning his commission. Not sure where they got that. I don’t have Heitmann’s register; wonder what that states. John Carroll, another Custer/7th Cavalry scholar in They Rode With Custer doesn’t mention Larned resigning; citing his appointment as instructor of drawing in July 1876, but receiving the rank of “Colonel, acting” in 1902. “Acting”? This implies to me he did resign and taught at West Point as a civilian and received his “acting” colonel rank as an honorary title. Don’t know. Wonder if there is an historian or librarian at West Point who could clear this up. The link you provided didn’t work.

As I mentioned, there is a fair amount on Larned in Darling’s Dakota transfer book. Larned was a correspondent for the Chicago Inter-Ocean during the 1873 Yellowstone Expedition providing escort for the NPRR survey. Custer, knowing this, tried to get on his good side as to be the beneficiary of favorable press coverage. His father died when he was 14 and apparently his mother, Mary Hobbs Larned, was a woman of some influence. Larned was not favorably looked upon by fellow officers; Godfrey writes in his diary that General Terry was “mad” at the news of Larned’s appointment to West Point; Godfrey labelling Larned a “systematic shirk”.

LikeLike

Steve… Here are a couple of sources for you. The first is the U.S. Army Register for 1891. Larned is listed on page 245 under the section of Professors at the Military Academy with pay as Colonel dating from 25 July 1876. https://archive.org/stream/officialarmyregi1891unit#page/245/mode/1up

The Association of Graduates Annual Reunion 1912 edition detailed his life and career in the Necrology section beginning on page 30 (image 40). http://digital-library.usma.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/aogreunion/id/14018/rec/6

And the Cullum Register of Officers and Cadets of the United States Military Academy can be found in the various volumes, or Bill Thayer’s consolidated version online at http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Gazetteer/Places/America/United_States/Army/USMA/Cullums_Register/2339*.html

LikeLike

Sam, if you look at page 243 of the USMA register, you will see the listings of all instructors and professors. Note that instructors and assistant professors are listed by their army ranks. Those with the tilte “professor” are not. There is one exception to this, Major John W. Clous, Judge Advocate, with an asterisk *by assignment under act of 6 June 74. There is no military rank next to the name Charles Larned. He is listed as receiving the PAY of colonel. Do you think he was a First Lieutenant getting a full bird colonel’s pay?? If he did not resign his commission, and retired a colonel, what are his dates of rank for Captain, Major, and Lt. Colonel? Do you think he was promoted from 1Lt. to full colonel just for teaching drawing? I don’t know who Mr. Thayer is; the links don’t work at least on my laptop (page cannot be displayed) but three of my sources have him resigning his commission in 1876; most likely to take the Professor job at higher pay than his army rank of 1st Lt. It would make sense; then too, he had medical issues and not being a rugged sort suited to frontier army duty he would have desired rear echelon type assignments.

LikeLike

Steve… Heitmann is a great reference, particularly for officers that did not attend West Point. I can’t say why he states that Larned resigned his commission. There is no indication in the Army and West Point references that I’ve consulted that he ever resigned. I tried to locate his personnel documents on Fold3, with no luck. Clearly he went from being a 1st Lieut, 7th Cav., to being an Assistant Professor, to being a Professor. By 1890 he was paid as a Colonel, at a time when West Point professors were paid as Colonels or Lieutenant Colonels. I’m not sure when he began to be paid as a Colonel. He is listed in the 2005 Register of Graduates and Former Cadets of USMA as being a Colonel. His Obit photograph shows him an elderly man in uniform, and although the rank is not visible, I have no doubt that he is wearing colonel insignia. Permanent professors at West Point today continue to hold their current rank/commission, and are considered for promotion in due course with their respective cohort year group. They can serve as colonels to the age of 64, thus they often are the last members of their class still on active duty, and upon retirement, are promoted to Brigadier General, often called a “tombstone promotion.” I have not done any research, nor do I care to, on the history of West Point professors and the history of their promotions or commissions. I will leave judgment as to the character of Larned to his peers and whether we was or was not a “shirker” or “coffee cooler” or “showed the white feather.”

LikeLike

This post was updated in 17 September 2020 to add in Capt. W. S. Edgerly’s 29 December 1890 letter to his wife describing Wounded Knee. The letter was published in February 2020 on an online auction website detailed in footnote 1.

LikeLike