I was hit early in the fight.

First Lieut. John Kinzie at Pine Ride in the summer of 1891.

The first published account of the battle at Wounded Knee from an officer present on the field came from an infantryman that had no official role in the battle and in all likelihood should not have been there. First Lieutenant John Kinzie was the forty-year-old adjutant of Colonel Frank Wheaton’s 2nd Infantry Regiment. The regiment was camped at the Pine Ridge Agency adjacent to the 7th Cavalry. The only indication of Kinzie’s reason for being at Wounded Knee on December 29, 1890, mentioned in the volumes of documents surrounding the campaign and Major General Miles’ investigation of the battle, came from a list of casualties compiled by Miles on January 3. He states that Kinzie was “by permission with Major Whiteside [sic].” A logical explanation of Kinzie’s presence at Wounded Knee would be as a liaison from the regiment to which Major Whitside was ordered to turn the Indians over to at Gordon, Nebraska, after securing the arms and ponies from Big Foot’s band.[1]

Kinzie probably came out to Wounded Knee the evening before the battle with Colonel James W. Forsyth and the 2nd Battalion of the 7th Cavalry. Regardless of the reason for being at Wounded Knee that day, Kinzie was shot at the onset of hostilities. His injury was such that he was returned to Fort Omaha, Nebraska, for recuperation in the following days. It was upon his arrival there that a reporter from the Omaha Bee caught up with the lieutenant on January 5 and recorded the first personal account of the battle from an Army officer.

The fight was a big surprise to all of us, as there hadn’t been a move to indicate that the Indians intended treachery. The Indian camp was in the bend of the ravine and the bucks were drawn up in front of their camp last Monday morning at 9 o’clock for the purpose of disarming them. The troops were dismounted and drawn up across the bend, and several detachments were deployed on the other side of the ravine to prevent the Indians from escaping in that direction. When they were called out they were told to hand over their arms, but they said they had none. Twenty of them were then told off, and sent to the tepees to get their guns. They returned with just one gun. A squad of soldiers was then sent to search the tepees, and they found about forty guns, although many of them were not apparently of much account. During this time the medicine man had been going through a kind of ghost dance, swinging his arms over his head and singing. He was finally ordered to sit down, but he looked very angry, and instead of obeying, he went clear around the bunch of Indians and finally sat down near Big Foot, who was sick with pneumonia and was huddled up on the ground under an old quilt. I had been standing with Major Whitside and Colonel Forsyth, and had received telegrams to send to General Brooke, presumably informing him that everything was peaceable, and had just gone to get into the wagon to drive to the agency. The order had been given to search the persons of the Indians and one or two had searched when I heard a sergeant say, ‘Look out.’

The medicine man grabbed a handful of dirt and threw it into the air. That seemed to be the signal. The first move was made by an Indian, who raised a big knife and tried to stab Phil West [sic: Wells], the interpreter, who was standing near Big Foot. West threw up his arm just in time to stop the blow, but the knife was just long enough to reach his nose, and it cut off the end of it as clean as could be. Just then another one of them stabbed Father Craft, and then the whole outfit threw open their blankets, pulled up their Winchesters and began to pump them for all they were worth. Then, of course, the troops began to return their fire, and for a while it was awful hot there. My horses started to run away, but finally wound up right in the thickest of it, where they stopped. I was hit early in the fight. The ball apparently struck one of the spokes and glanced upward, striking me just above the heel. It slid around, just grazing the ankle bone, and then passed out at the top of my overshoe. It was 9 o’clock when the fight began, and it was nearly 10 o’clock when the final skirmish firing was concluded. The hand-to-hand fight lasted only a few minutes, when the Indians broke and tried to get to cover. When the Indians were first called out the squaws had rounded up the ponies and began taking down the tepees and packing the saddles. When the firing began the squaws started to run. Some of them tried to cross the ravine and others rushed into the tepees. Some of them crowded into the wall tent that had been put up for Big Foot. The bucks sought the same shelter, and then began picking off the soldiers. It became necessary to dislodge them, and the Hotchkiss threw in a few shells, which tore up the tents and burned them. One Indian was roasted in Big Foot’s tent in this manner as completely as though baked in a brick oven. It was not intended to shoot down the squaws, although some of them were undoubtedly as bad as the bucks, but they could not be singled out. They got mixed up with the bucks and had to suffer with them. No one fired on a squaw intentionally. The result shows this to be so.

There were 119 bucks, and only one of them went scott free. Six got away, but five of them were badly wounded. There were 450 in the whole band, including women and children, and as only 180 were killed, of whom 113 were bucks, it shows that the greater part of the squaws and children escaped. I don’t think that we had the whole of Big Foot’s band in that bunch, because more Indians came up and attacked the soldiers on the hills after the fight was nearly over. I am of the opinion that they comprised the remainder of Big Foot’s band.

The Indians kept up the fight, and some of them sought shelter in a shallow cave on the side of the ravine and could not be dislodged. They picked off soldiers as fast as they showed themselves, and finally a shell was sent straight in there from the Hotchkiss. There wasn’t anything left of the Indians. Captain Wallace was killed with a war club, of which there were a great many on the battlefield. He was struck twice across the forehead, apparently by different instruments. He was also shot. When they found him his hand was raised, and in it was clenched his revolver. Every chamber was empty, and grouped around him were five dead Indians. He had done good work before he died.

It is not true that many of the soldiers were shot by their own comrades, although it is possible that a few were hurt in that way, as it was so terribly mixed up for a few minutes. The machine guns did good work, but the most of it was done with the musketry.

The attack on the agency could hardly be called a fight, as the Indians were out on the hills and fired at long range, and the soldiers did not return it. The situation up there is pretty badly mixed, and I think the Indians will soon be fighting among themselves. I would not be surprised to see in tomorrow’s dispatches that such is the case. The friendlies and hostiles are considerably at outs. General Miles reached the agency several days before I left. I heard nothing of Colonel Forsyth being relieved of his command until I saw it in this morning’s paper on the train. Nothing was heard at the agency of an officer being arrested for insubordination. I doubt if it is true.

It is hard to tell what the outcome will be. There are now about three thousand troops in the field and four thousand Indians, of whom about one thousand are bucks in good fighting trim. Many of the reds raising a disturbance about the agency are young bucks, and it is their first experience.[2]

Captain Charles B. Ewing, assistant surgeon for the Department of the Platte, whose presence at Wounded Knee also was little more than an observer, provided some detail of Lieutenant Kinzie’s wounding in a report he submitted directly to General Miles the following June.

Lieutenant Kinzie, Second United States Infantry, Mr. James Assay, Indian trader at Pine Ridge agency, and myself, were seated in an open wagon within ten to fifteen feet of one end of the parallelogram of soldiers that surrounded the Minneconjous Sioux band under Big Foot.

Colonel Forsyth, Seventh United States Cavalry, was writing a communication which one of our party was to carry to General Brooke, commanding Department of the Platte, then at Pine Ridge agency, and while waiting for communication, the firing commenced. A volley came in our direction, the bullets whistling unpleasantly about us; our horses took fright, and, becoming uncontrollable, ran right across the line of fire, but were turned, and finally stopped near Louis Mossoeu’s store, about three hundred yards distant from the field of battle; we alighted, and I was then informed by Lieutenant Kinzie that he had been shot in the foot; after examination of the same, I immediately returned to the camp and busied myself in the care of the wounded.[3]

Following the campaign, Lieutenant Kinzie became the source of the only court martial to stem from the Sioux Campaign of 1890-1891 when he brought charges against Captain Henry Catley, C Company, 2nd Infantry, for cowardice during the campaign. Catley, at fifty-five, suffered from a number of ailments and declined to take the field with his company when called to defend the Pine Ridge Agency at the end of December 1890. Ultimately he was acquitted of cowardice, but medically retired as a result of the trial.[4]

Born on August 19, 1850, possibly at Burlington, Kansas, John Kinzie was the eighth child and third son of Robert Allen and Gwenthlean Harriet (Whistler) Kinzie. Robert Kinzie, born in 1810 at Fort Dearborn, was the youngest child of John Kinzie and Eleanor Lytle, widow of Daniel McKillip, a British militia officer. His father was a trapper in the Michigan territory and founded the town of Chicago; the family were survivors of the Fort Dearborn massacre of 1812. Robert’s mother, Eleanor, had been abducted in Western Pennsylvania by Seneca Indians as a young girl along with her mother, brother, and sister. Despite her family being ransomed soon after the abduction, Eleanor remained with the tribe for years before being reunited with her family. Robert married Gwenthlean at Chicago in 1834. She was the daughter of Colonel William and Mary Julia (Fearson) Whistler, born in 1818 at Fort Howard in the Michigan territory, what is now Green Bay, Wisconsin.[5]

Interestingly, the Kinzie and Lytle connection made First Lieutenant John Kinzie of the 2nd Infantry twice the second cousin of Colonel James W. Forsyth, commander of the 7th Cavalry at Wounded Knee. Forsyth’s grandfather was William Forsyth, half-brother of John Kinzie, the founder of Chicago. Moreover, William Forsyth married Margaret Lytle, the older sister of Eleanor Lytle, making Forsyth and Kinzie second cousins through their grandmothers as well.[6]

Robert and Gwenthlean settled in Burlington, Kansas where he was a farmer. During the Civil War, he served as a paymaster in the Union Army and rose to the rank of major with a brevet of lieutenant colonel. Having a personal association with Ulysses S. Grant, Robert was able to secure officer commissions for three of his sons: David Hunter Kinzie, born in 1841, served during the Civil War where he received a brevet to major for meritorious service, and ultimately rose to the rank of brigadier general; Francis Xavier Kinzie, born in 1853, was commissioned a second lieutenant on 1874, a year after his father’s death, and resigned his commission in 1879; John Kinzie was appointed a second lieutenant in 1872. Robert Allen Kinzie returned to Chicago following the war and died in 1873. Gwenthlean died in 1894 while residing with her son, John, at Fort Omaha, Nebraska.[7]

John Kinzie married Myra Grace Bowles in her native state of Vermont on April 18, 1872. He was twenty-one and she, twenty. Myra was the daughter of Joseph Lewis and Juliettte (Brown) Bowles, an inn keeper in Washington, Vermont. Three months after their marriage, Kinzie accepted his commission as a second lieutenant in the 2nd Infantry on July 27, 1872, and was stationed at Mobile Barracks, Alabama. The Kinzies had two children while in Alabama, Grace (later Mrs. Paul Holbrook), born in 1874, and Robert, born in 1875. Kinzie next was stationed at Fort Lapwai, Idaho Territory, followed by assignments to Camp Chelan and later Fort Spokane, Washington Territory. He returned to the Idaho Territory at Fort Coeur D’Alene, where he and Myra had two more daughters, Gwenthlean, or Gwendolyn, born in 1880, and Eleanor (later Mrs. Augustus J. Rich), born in 1885. Their last child, Julia (later Mrs. Claude A. Halley) was born at Fort Omaha, Nebraska, in 1889. Kinzie was promoted to first lieutenant in 1879 and captain in 1892, little more than a year after being wounded at Wounded Knee.[8]

Captain John Kinzie was retired for disability in December 1897 and settled in Seattle, Washington. He served for four years as commandant at Washington State College at Pullman. In 1902, Kinzie was appointed a lieutenant colonel in the Washington National Guard where he served on the Governor’s staff as an inspector and instructor stationed at Olympia. In April 1910, Kinzie ran afoul of the state adjutant general, General Lamping, who requested the War Department remove Kinzie accusing the officer of drawing pay for services as instructor of militia while on duty at encampments and during inspections. He also asked that the 60-year old Captain Kinzie be replaced with a younger man. Kinzie countered with charges that the military organization of the Washington National Guard had steadily declined since Lamping assumed duties as Adjutant General and recommended that Lamping resign. The War Department telegraphed Kinzie its congratulations for his “honorable, straightforward and efficient work,” and informed him that Lamping had requested that he be relieved, to which Kinzie complied.[9]

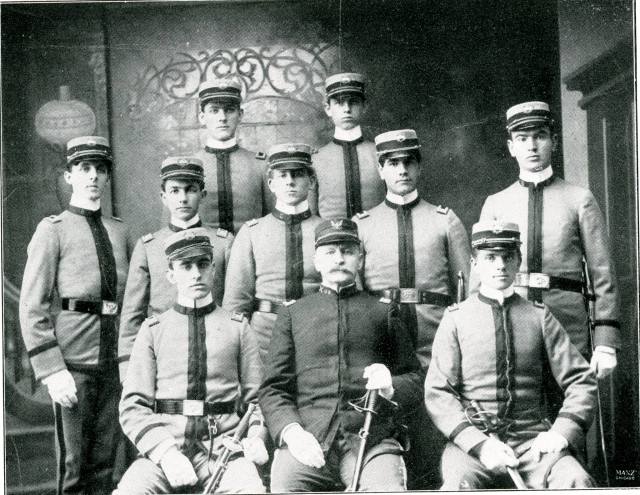

Capt. John Kinzie with his staff and line cadet officers during his first year at Washington State College. From the 1902 (published in 1901) Chinook year book.[10]

In 2017, during construction at the East Lake Cemetery in Seattle, John Kinzie’s cremains were discovered. He was inurned, or re-inurned, at the Washington State Veterans Cemetery at Medical Lake on 3 October, 2017, during a ceremony in which more than forty veterans’ ashes were laid to rest. The remains were delivered by a procession of veterans on motorcycles.[12]

Capt. John Kinzie was interred in the Washington State Veterans Cemetery at Medical Lake, Washington in 2017.

Endnotes:

[1] Nelson A. Miles, letter dated 3 Jan 1891 to Adjutant General’s Officer, National Archives Microfilm Publications, “Reports and Correspondence Related to the Army Investigations of the Battle at Wounded Knee and to the Sioux Campaign of 1890–1891.” (Washington: The National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration, 1975 ), 788; The picture of Lieut. Kinzie is cropped from a photograph taken by Clarence G. Morledge in June or July 1891, available at digital collections of the Denver Public Library (http://digital.denverlibrary.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15330coll22/id/23966/rec/1) accessed 10 Nov 2019. General John J. Pershing identified John Kinzie in the photograph in a letter to Elmo S. Watson dtd 24 Mar 1943, kindly provided by Mark L. Gardner, email to author dtd 10 Nov. 2019.

[2] Omaha Daily Bee, “The Fight at Wounded Knee,” 6 January 1891.

[3] George B. Shattuck, ed., The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, Volume CXXVI, January – June 1892, (Boston: Damrell and Upham, 1892), 463-464,

[4] Omaha Daily Bee, 10, 17, 21 and 29 Mar 1891.

[5] Ancestry.com, United States Federal Census [database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009, Year: 1860, Census Place: Burlington, Coffey, Kansas Territory, Roll: M653_347, Page: 764, Image: 176, Family History Library Film: 803347; Juliette Augusta Magill Kinzie, Narrative of the Massacre at Chicago, Saturday, August 15, 1812, and of Some Preceding Events (Chicago: Fergus Printing Co., 1914), 47. An outstanding source regarding the massacre at Fort Dearborn, and the abduction and captivity of Eleanor Lytle is Lieutenant Linai T. Helm’s The Fort Dearborn Massacre, edited by Nellie Kinzie Gordon and published in 1912 in Chicago by Rand McNally and Company.

[6] Ann Durkin Keating, Rising Up from Indian Country: The Battle of Fort Dearborn and the Birth of Chicago, (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2012), 44-45.

[7] United States Federal Census, Year: 1870, Census Place: Chicago Ward 20, Cook, Illinois, Roll: M593_211, Page: 366B, Image: 306, Family History Library Film: 545710; Historical Data Systems, comp., U.S., Civil War Soldier Records and Profiles, 1861-1865 [database on-line] (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2009); Ancestry.com, U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962[database on-line] (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012); National Archives Microfiche Publication M1395, “3702 ACP 1874: Kinzie, Francis X..,” Letters Received by Commission Branch, 1874-1894, 58; Ancestry.com, U.S., Select Military Registers, 1862-1985 [database on-line] (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2013) publication 1912, 441.

[8] Ancestry.com, Vermont, Vital Records, 1720-1908 [database on-line] (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2013) image: 3626; United States Federal Census, Year: 1860, Census Place: Washington, Orange, Vermont, Roll: M653_1323, Page: 612, Image: 624, Family History Library Film: 805323; Year: 1870, Census Place: Washington, Orange, Vermont, Roll: M593_1622, Page: 489B, Image: 546, Family History Library Film: 553121; Year: 1880, Census Place: West Durferin, Stevens, Washington, Roll: 1397, Family History Film: 1255397, Page: 88A, Enumeration District: 064.

[9] United States Federal Census, Year: 1910, Census Place: Seattle Ward 3, King, Washington, Roll: T624_1659, Page: 1B, Enumeration District: 0093, FHL microfilm: 1375672; “Charge Brews in the N. G. W.,” The Evening Statesman (Walla Walla, WA: 4 Apr 1910), 1; “Capt. Kinzie’s Report,” The San Juan Islander (Harbor, WA: 22 Apr 1910), 2.

[10] Junior Class of the Washington Agricultural College and School of Science, Chinook, 1901, page 58, (1902 cover date), from Washington State University Digital Collections (http://content.libraries.wsu.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/chinook/id/3841/rec/1).

[11] Ancestry.com, Washington, Select Death Certificates, 1907-1960 [database on-line] (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014) FHL Film Number: 1992077, Reference ID: cn2042 and FHL Film Number: 1992192, Reference ID: 1656; Pullman Herald, “Death of Captain Kinzie,” 14 Aug 1914; The Vancouver Independent (Vancouver, WA: 8 Jun 1882), 5.

[12] “Forgotten remains of Washington veterans arrive in Medical Lake with motorcycle escort,” The Spokesman-Review (Spokane, WA: 30 Aug 2017 https://www.spokesman.com/stories/2017/aug/30/forgotten-remains-of-washington-veterans-arrive-in/ accessed 10 Nov 2019) ; Find A Grave, database and images (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/176646896/john-kinzie : accessed 10 Nov 2019), memorial page for CPT John Kinzie (19 Aug 1850–10 Aug 1914), Find A Grave Memorial no. 176646896, citing Washington State Veterans Cemetery, Medical Lake, Spokane County, Washington, USA ; Maintained by Peter Joseph (‘PJ’) Braun (contributor 46869838); “Unclaimed Cremains Interment – Washington State Veterans Cemetery,” Washington State Department of Veterans Affairs (https://www.dva.wa.gov/unclaimed-cremains-interment-washington-state-veterans-cemetery-1, accessed 10 Nov 2019).

Citation for this article: Samuel L. Russell, “First Lieutenant John Kinzie, Adjutant, 2nd Infantry – An Officer’s Account of Wounded Knee,” Army at Wounded Knee (Sumter, SC: Russell Martial Research, 2013-2015, http://wp.me/p3NoJy-yX), updated 10 Nov 2019, accessed date __________.

I enjoyed this sequence. Very interesting.

Regards

Susan

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLike

I am kin to John Kinzie, His brother David Hunter Kinzie was my great grandfather. Thank you for this info. I have been working on our ancestry for many years.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I too, am a direct descendant of John Kinzie and his first wife Margaret Mckenzie, Kinzie, Hall and descend from their first born son William Kinzie, who was born around 1791. Being from Nebraska I had known Robert Kinzie’s son had been stationed at Fort Omaha and his mother lived there also. I had no clue as to what happened to John after he left Omaha and I sure didn’t know he got shot in the foot at Wounded Knee. I’ve tried to find where he is buried but all I’ve come up with is that he died in 1914 in Seattle. I had just told Cindy Mcanelly about this and shared the John Kinzie’s picture with the story. Is there anyway I could get a copy of that picture? Anyway, I love finding new things about my ancestors.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Once again, I want to thank you for all of the information on John Kinzie’s part in this. The Wounded Knee Massacre was awful.

LikeLike

When I heard John Kinzie managed to find his way over to Wounded Knee, I was not very happy. I don’t know long long he was there but did get shot in the foot. what happened to those poor Indians was awful. I used to not like Indians very well, as a group of them stole Margaret and elzabeth McKenzie from their house after scaring of the families horses. The dad and brother went off to get the horses and meanwhile there was scalping of their mom, a baby and I’m not sure who else. After the two young ladies were released to John Kinzie and Trader Clark, their father Moredoch Mckenzie finally found them and the girls returned back to Virginia, minus one young son of Elizabeth’s who was kept behind and eventually became part of Tecumseh’s Army and died with him at the Battle of the Thames. Andrew Clark was his name and he was found the next morning still alive and was able to tell what he saw. I’d love to know whatever became of his body. Probably rotted away where he went down. My family had a lot of interesting stories to tell. The John Kinzie at wounded Knee went back to Omaha and later went to the Northwest. I have no idea of what became of him and his family. But seeing pictures of wounded Knee, with frozen Indians in the snow makes me sick. Margaret, my 4th great grandmother who had children with thee John Kinzie of Chicago, had trouble getting used to white man’s ways, though she did remarry and have more children. Elizabeth was more or less the same way. what lives those people had. The John Kinzie picture in the picture, in the front row, was a son of thee John Kinzie’s son Robert Kinzie and his mother was a Whistler who died at fort Omaha when her son was out scouting. she was later sent back to Chicago for burial.

LikeLike

Ms. Scheer… I recently learned that Capt. John Kinzie was cremated in 1914, but for some unexplained reason, his cremains were lost. They were discovered recently by the Missing in America Project. This past February a group of Patriot Guard Riders escorted his cremains to the Washington State Veterans Cemetery at Medical Lake where they will be interred this fall. You can read more at the following article in the Spokesman-Review:

http://www.spokesman.com/stories/2017/aug/30/forgotten-remains-of-washington-veterans-arrive-in/#/0

A photo of Capt. Kinzie was posted on an Indian Wars forum. Kinzie is the seated officer in the center surrounded by cadets at Washington State College, circa 1901.

LikeLike

On 3 October 2017, Captain John Kinzie was interred at the Washington State Veterans Cemetery at Medical Lake with full military honors… he & 40 other veterans & their spouses (found by volunteers from the Missing in America Project (www.miap.us) were given their final honors.

Representatives of the five branches of the military, governmental officials, various veterans groups, including the Yakima Warriors, Patriot Guard Riders, American Legion Riders & Combat Veterans Association escorted the cremains of these military men & women to their final resting place.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Details of the ceremony when Captain Kinzie was interred at the Washington State Veterans Cemetery in August 2017 can be read at Forgotten remains of Washington veterans arrive in Medical Lake with motorcycle escort.

LikeLike

Your information on all of this is so interesting, I hope you can come up with interesting facts.

LikeLike

This post was, originally published 3 Dec 2014, was updated 10 Nov 2019 to include the cropped picture of Lieut. Kinzie in 1891 and details of his internment in 2017.

LikeLike