I was not aware that Big Foot or his people were considered hostile, and am now at a loss to understand why they were so considered, every act of theirs being within my experience directly to the contrary, and reports made by me were to the effect that the Indians were friendly and quiet.

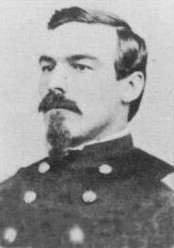

Edwin Vose Sumner, Jr., was fifty-five during the Pine Ridge Campaign of 1890-1891. Perhaps destined to serve in the cavalry, he was born in 1835 at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, where his father had established and was commanding the Army’s school for mounted troops. Sumner began his military service as a volunteer when he enlisted at the outset of the Civil War. During the course of the rebellion, he rose to the regular rank of captain in the 1st U.S. Cavalry, and was serving as a lieutenant colonel of U.S. Volunteers in the 1st New York Mounted Rifles. He received a brevet promotion to major for gallantry in the battle of Todd’s Tavern in 1864. At the end of the war he was awarded a brevet of brigadier general in the volunteers and a brevet of lieutenant colonel in the regular army, both for gallant and meritorious service. After the war he reverted to his regular rank of captain serving with the 1st Cavalry until promoted to major in the 5th Cavalry in 1879. Sumner was promoted to lieutenant colonel in the 8th cavalry in April 1890, the rank and position he held during the Pine Ridge Campaign.[1]

The same month that Sumner joined the 8th Cavalry, Brigadier General Thomas H. Ruger, commanding the Department of Dakota, ordered a camp be established on the Cheyenne River just south of the Indian reservation of the same name. The troops were there expressly to observe a band of Minicounjou Lakota under the chieftainship of Big Foot, also known as Spotted Elk. Captain Argalus G. Hennisee, commanding Troop I, 8th Cavalry, referred to the field site as the Camp on Cheyenne River, S. Dak., or more briefly, Camp Cheyenne. In the first post return, Hennisee wrote:

This inset is cropped from Brigadier General John R. Brooke’s campaign map and depicts Camp Cheyenne–the black flag–across the river from Big Foot’s village.[3]

The troops reported on this return left Fort Meade, S.D., Apr. 6, ’90 equipped for field service… April 2, 1890, arrived at this camp on the north bank of the Cheyenne River, S.D., 8 miles below the junction with the Belle Fourche, April 10, 1890. Distance from Fort Meade 77 miles. Distance from Rapid City, S.D., the nearest telegraph office, about 68 miles. Distance from Smithville, Meade Co., S. Dak., nearest post office, 25 miles by road, 23 miles by trail.[2]

Captain Hennisee went on to describe the Indians that he was ordered to observe, and indicated that they were not hostile.

The camp is about 1 mile from the village of “Big Foot” or Spotted Elk, the Chief man of the Cheyenne River Indians in the Cheyenne River Valley now living off the reservation. They are living in four villages along the river from three miles below junction to about three miles east of the S.W. corner of the near reservation, on the south side of the river. Number of Indians, including children, about 396–are living in log houses where they have lived for years, but, off the near reservation. They are peaceably disposed and have committed no depredations on the settlers of Meade County.[4]

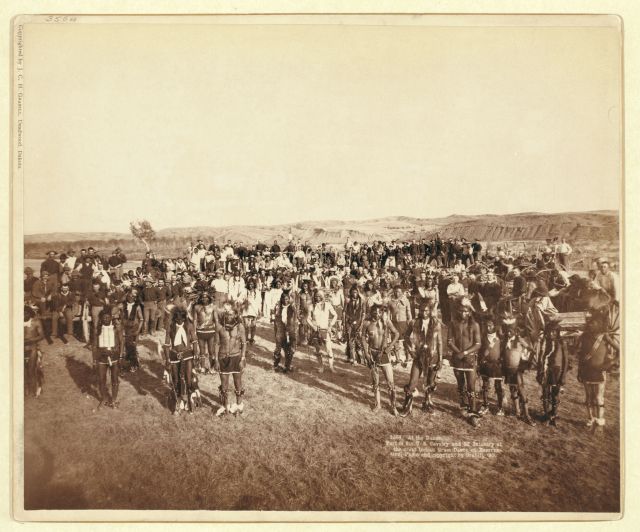

Relations between the soldiers at Camp Cheyenne and the Indians they were ordered to observe appeared to be amicable. At the end of the summer, photographer John C. H. Grabill captured a number of pictures of the soldiers of the camp and members of Big Foot’s band.

(Click to enlarge) “At the Dance. Part of the 8th U.S. Cavalry and 3rd Infantry at the Great Indian Grass Dance on Reservation. Photo and copyright by Grabill, ’90.” According to Jensen, et al., Eyewitness at Wounded Knee, 14, John C. H. Grabill took this photograph of Big Foot’s band in August 1890. Captain Argalus G. Hennisee of Troop I, 8th Cavalry, established Camp Cheyenne in April 1890 to observe Big Foot and his band of Miniconjou.[5]

It was my first experience with the Indians, and it was the hottest time I ever had. We had camped on a flat near the Cheyenne river, and when he couldn’t seriously annoy us otherwise Big Foot undertook to burn us up. He started fires at the same time in a circle several miles from our camp, and they burned in.

But, our commanding officer, Capt Hennissee, was too wise for Big Foot. He had already burned a plat three miles square where we had pitched our camp, and the flames didn’t reach us. But, my, it was hot in there while that fire burned. The trees were cedar, and they cracked when the flames struck them with a noise like revolver shots.

That was the closest call I had with Big Foot’s band of Indians. The detachment I was with had orders not to fire on the Indians except as a last resort. Big Foot found this out, and as a result was very brave in his attempts to annoy us. He brought his painted tribe one night with their tom-toms and held a war dance right in our camp. But, under the orders, the commanding officer let them alone, and he rode away, daring the soldiers to come out and get him.

He got too gay one day and his bluff was called. One troop of cavalry was out scouting by itself, and Big Foot and his entire tribe met it. Big Foot detailed two braves to seize the horse of each cavalryman and turn it back to camp. They went back in view of their orders not to fire until necessary.

When Capt. Hennissee saw them he was red-hot. ‘Go back,’ he said, ‘and stay there.’ The lieutenant in command ordered his men to draw their pistols. Then they rode back. Big Foot saw they meant business and quit his bluffing.[6]

By early fall 1890 Perian P. Plamer, the Indian agent for the Cheyenne River Reservation, had formed a different opinion of Big Foot and his band of Miniconjou. Writing on October 10, Palmer anxiously described the situation as he saw it:

A number of Indians living along the Cheyenne River and known as Bigfoot’s Band are becoming very much excited about the coming of a messiah. My police have been unable to prevent them from holding what they call ghost dances. These Indians are becoming very hostile to the police. Some of the police have resigned. Information has been received here that the same excitement exists at other agencies.

Nearly all of these Indians are in possession of Winchester rifles, and the police say they are afraid of them, being armed only with revolvers.[7]

During this same month, Captain Hennisee blandly reported that his troops, “performed the usual camp and escort duties,” with no indication that there was concern for Big Foot’s band. By the end of November Agent Palmer’s reports indicated a crisis was at hand.

The Indians are dancing continually…. Big Foot, ordered all the Indians belonging to the ghost dance to procure all the guns and cartridges possible to obtain and to stay together in one camp. There is no longer any doubt that the Indians are all well supplied with the best make of guns and cartridges, and in addition to rifles a large majority of them have revolvers. There is positive proof that some of the traders have been supplying the Indians with guns. The friendly Indians say that the dancers want to fight and will fight soon, but will not let them know anything.[8]

Captain Hennisee moved Camp Cheyenne about eight miles on November 24, and five days later Lieutenant Colonel Sumner was ordered to take command of elements of the 3rd Infantry and 8th Cavalry that were stationed at the camp. Sumner became a key individual during the campaign when he was ordered in the latter part of December to arrest and disarm Big Foot and his band. The cavalry officer drew the ire of the commander of the campaign, Major General Nelson A. Miles, when Big Foot’s band slipped away at night and headed south toward the Pine Ridge Reservation.

Sumner was directed to furnish a report to his department commander, Brigadier General Ruger, following the campaign at the end of January 1891. His report is critical in detailing the actions of the army elements ordered to observe and later arrest Big Foot’s band, and the actions of the group of Lakota when they fled south. Colonel Sumner’s lengthy report is provided here in its entirety. I have embedded the many enclosures he provided at the points in his report where he refers to each in an attempt to make the report more readable. I have excluded the lengthy sworn statements provided by Mr. John Dunn and Interpreter Felix Benoit and will present them in a separate post.

As with my posts in Hunting for Big Foot, hover the mouse over the names displayed in Red to display the full identity of the individual mentioned. Bold Red will also indicate location of the individual. Blue underlined texts are hyperlinks to other pages or cites. Also provided is the following map with inset depicting the location of Big Foot’s village and Camp Cheyenne with the location of key individuals mentioned throughout the report. Clicking on the map will open it in a new tab with an enlarged view that can be zoomed in for greater detail. Having this inset open and available in a separate tab is a useful reference while reading the report.

(Click to enlarge) “Map of the Pine Ridge & Rosebud Indian Reservations and Adjacent Territory,” prepared under direction of Chas. A. Worden, 7th Infantry, Acting Engineer, Department of the Platte, from 1890 authorities, with inset showing disposition of forces on 22 Dec. 1890.[9]

Fort Meade, S. Dak., February 3, 1891.[10]

The Assistant Adjutant-General, Department of Dakota:

Sir: I have the honor to acknowledge receipt of your communication directing me to submit a report of the flight of Big Foot’s band from Cheyenne River, and all circumstances connected therewith. In compliance therewith I respectfully submit the following statement:

On my arrival on Cheyenne River, December 3, reinforcing the command there under Capt. Hennisee, Eighth Cavalry, with D Troop, Eighth Cavalry, I took command of troops in the field. This command, then was C, D, and I Troops, Eighth Cavalry, and F Company, Third Infantry (later C Company, Third Infantry), and two Hotchkiss guns. My instructions were set forth in Post Orders No. 254, dated Fort Meade, S. Dak., November 29, and telegraphic instructions from headquarters Department of Dakota:

Barber to Commander, Fort Meade, S. Dak. (Nov 27): Send Troop D, Eighth Cavalry, Godwin, to join command in the field on Cheyenne River, and direct Col. Sumner to take command of full force. He may move the camp nearer Smithville if he thinks it will be better to enable him to keep the region of the east of between the Cheyenne and White River under observation, keeping at the same time the village of Big Foot under control, and giving assurance of safety to the people in the region about it.

Is probable command of Capt. Wells may be soon spared from its present place of duty, when it is intended to order it to join the command of Col. Sumner and put a stop to the unauthorized going back and forth of parties between the upper and lower Sioux Reservation. Acknowledge receipt. By command Gen. Ruger.In compliance with these instructions I moved the camp up the Cheyenne River nearer to Smithville, and opened a trail directly east over the hills and established an outpost at Davidson’s ranch, 20 miles east of my camp at head of Deep C[r]eek, and on the trail between Big Foot’s village and Pine Ridge. This trail was not practicable for wagons, but could have been used by cavalry, and the outpost was established to give information of any Indians passing north or south.

My orders specified protection to settlers on Belle Fourche and vicinity, as well as a watch on Big Foot’s camp. A few days after my arrival most of the chiefs and head men called to see me, including Big Foot. They remained two days about my camp, and without exception, seemed not only willing but anxious to obey my orders to remain quietly at home, and particularly wished me to inform my superiors that they were all on the side of the Government in the trouble then going on. This information was furnished December 8th, by letter dated Camp Cheyenne:

Sumner to Miles (Dec 8): I have just held a council with all the principal chiefs in this section of the country, and find that they are peaceably disposed and inclined to obey orders; but from their talk, as well as from reports I have received from officers here and others, I believe they are really hungry, and suffering from want of clothing and covering. I advise that 1,000 rations be sent me at once for issue to them, and authority to purchase a certain amount of fresh beef. [Two days later General Miles made reference to this message in a telegram to the Adjutant General of Army stating, “Colonel Sumner reports quite a large number in his vicinity who are willing to obey his orders. These belong to Big Foot’s following and others located about the southwestern part of Cheyenne River reservation.”]

Also in the letter from the same camp, dated December 12:

Sumner to Brooke (Dec 12): Your dispatch, 11th received. Have sent a troop of cavalry on Territorial Road, east of Smithville, to Mexican Kid’s, at intersection of road from Pine Ridge to Grindstone Buttes. Will catch the Indians if possible, but have not cavalry enough to cover this country as it should be and watch Indians here. When will the two troops of the Eighth Cavalry report to me from Oelrichs, and what do you wish done with any Indians I may capture? Mail for this camp leaves Rapid City Mondays and Fridays 6 a.m., and daily courier from Meade.

Also in letter from same camp, dated December 16:

Sumner to Asst Adj Gen Dept Dakota (Dec 16): On receipt of your dispatch of the 14th, I brought Henisee into Smithville, patrolling the road east only. On 15th we connected with cavalry patrol of Sixth Cavalry from Camp at Box Elder Creek.

Your dispatch of 15th just received. Will withdraw my troops from Smithville to my present camp, patrolling to Smithville, and on all roads east of my camp. I believe Indians on Cheyenne River are under full control. I can get all necessary information through my scouts and others, and will keep you well informed.Frequent communication, and always friendly, was kept up with all these leaders until about December 15, when Big Foot came to my camp to say good-by, as he and all his men, women, and children were going to Bennett for their annuities, again assuring me that none of the Cheyenne River Indians had any intentions or thoughts of joining the hostiles at Pine Ridge.

Notwithstanding this assurance, however, I was at that time impressed with the idea that Big Foot was making an extraordinary effort to keep his followers quiet, and seemed much relieved at having succeeded in getting them to go to Bennett. With this impression on my mind it appeared to me that he required at that time all the support I could give him, and I never failed, in the presence of his own men and others, to show good feeling and the utmost confidence. About this date came the telegram from department headquarters, dated December 16th [following the killing of Sitting Bull and the subsequent flight of his Hunkpapa followers.]:

Barber to Sumner (Dec 16): It is desirable that Big Foot be arrested, and had it been practicable to send you Wells with his two troops, orders would have been given that you try to get him. In case of arrest, he will be sent to Fort Meade to be securely kept prisoner. By command General Ruger.

Under the circumstances, and owing to the delicate situation of affairs at that moment, as described above, viz, my belief that Big Foot could alone control the young men, and was doing so under my advice and support, I thought it best to allow him to go to Bennett a free man, and so informed division commander by telegraph December 18:

Sumner to Miles (Dec 18): Communication from Colonel Carr just received. Have information that Standing Rock Indians from Sitting Bull’s camp are coming to Cherry Creek to-day with the intention of getting those Indians to join them to go to Pine Ridge. Will try to prevent their leaving Cherry Creek, but have not force enough to cover all the roads in the country. Ordered by department commander to arrest Big Foot; he has started with Big Foot and other Cheyenne River Indians to Agency for annuities. If he should return I will try and get him; if he does not, he can be arrested at Bennett. Have scouts and policemen in camp on Cherry Creek to give me information. Only heard so far what I have already informed you, and am awaiting news from that point, and have one troop of cavalry near Big Foot’s village. Camp on the Cheyenne.

Also telegram to department headquarters same date:

Sumner to Asst Adj Gen Dept Dakota (Dec 18): It is reported to me that Standing Rock Indians will be on Cherry Creek to-day with intention of getting Cheyenne River Indians to go to Pine Ridge. Big Foot and his band left for the agency to draw annuities, and is on the way there now. Will know if he returns and advise you, and will learn all I can of the Standing Rock Indians, and what influence they have. Please acknowledge receipt. Sixth Cavalry has withdrawn from Box Elder to Rapid Creek, on Cheyenne River, last accounts.

Also telegram to division commander at Rapid City, dated December 19:

Sumner to Miles and Ruger (Dec 19): Your dispatch received. Latest reports to me from chief of police at Cherry Creek is that all the Indians on Cheyenne River and Cherry Creek have started for Bennett to get their annuities and they are beyond the influence of Standing Rock Indians. Expect to hear positively every hour and will send detachment down to Cherry Creek to-day. If the statement from the police is correct all Indians named are out of the game and might be held at the agency after they arrive.

My main camp is on Cheyenne River and on the main trail traveled by Cheyenne River Indians to Pine Ridge. Another trail east of here, 20 miles, runs from Cherry Creek to Pine Ridge. Another west of here, same distance, is used by Standing Rock and all northern Indians. I am watching all these as closely as possible and can prevent any considerable force from passing over either them. As regards Sitting Bull Indians, so far only one man and woman have arrived on Cheyenne River; quite a number of them, women and children, are west of me on Cherry Creek. The bucks, whom the troops are pursuing, started up Grand River and may circle to join those on Cherry Creek and start for Pine Ridge on the trail west of me, through the settlement. Every citizen in the country, as it were, on outpost duty; they all know where my camp is, and I fear to move with any considerable force north lest the Sitting Bull bucks should pass me on the west. I am also watching to prevent any force from Pine Ridge coming north on trails east of us. A small force of infantry at mouth of Cherry Creek would be in good position.I invite special attention to this dispatch as showing that every effort was being made to keep informed, to inform my superiors, and to make the most of my command, and in this connection, see copy of dispatch to Gen. Carr, Sixth Cavalry, dated December 19th:

Sumner to Carr (Dec 19): Your scout with dispatch reached me safely and in good time. I have given him a good rest, and he starts back to-day. Your letter by mail has also been received, and I sincerely hope we may meet before long, but, as you cover it. Gen. Ruger seems to think I ought to know all that is going on or is likely to take place, and still have my troops in camp, which can not be done. I inclose herewith a copy of a dispatch received by me last night at 11 o’clock. It strikes me that orders to me and some other commander have become mixed, either at headquarters or in transmission. Perhaps from your orders you will understand the matter better than I do.

The last heard from the Sitting Bull Indians is that families are near head of Cherry Creek, and the bucks may turn south to join them, and then all take old trails to Pine Ridge, crossing Belle Fourche west of me at Wood’s, Elk Creek at Viewfield, and so on south near your command at Rapid.

I am on the lookout for any move of that kind, and will give you due notice. I have cavalry on Cheyenne River as far down as mouth of Cherry Creek, and scouting party between Cherry Creek and Cheyenne River; a detachment at Quinn’s ranch, about 25 miles west of my camp and courier line between, to that point. Citizens living on Belle Fourche will give me due notice of Indians in that direction.

If occasion requires, I can supply any detachment of yours in this direction with rations and forage at my home camp, or will send out supplies to them.

Good bye and good luck to you if you meet the enemy.

P.S. December 19. (10 o’clock p.m.)—Since writing above your second courier has reached me with your letter of this date. I believe with Gen. Miles that numbers are exaggerated, and I feel confident of capturing the whole outfit if I can find it, but the trouble is there are so many trails throughout the country that it is almost impossible to watch all of them, and the Indians knowing where the troops are, will avoid them and probably travel by night. My cavalry is on the jump all the time and in every direction, as you know from having seen several detachments, and I will do my utmost to carry out orders and wishes of the authorities. I will send a party to Wood’s, on Belle Fourche, this afternoon. I will hold your second courier until to-morrow.Also letter to Mr.Dunn same date, on Belle Fourche:

Sumner to Dunn (Dec 19): After the killing of Sitting Bull the Indians in his camp left their camp; the bucks, about 100 in number, started up Grand River to westward, and the families came south toward Cherry Creek, and are now there well up on the creek. A force of soldiers is following the bucks, and it is supposed they will scatter and come to their families on Cherry Creek. From there they may attempt to come south, crossing Belle Fourche about Wood’s or some other place. I am sending this small party out to watch the crossings on the Belle Fourche and will be glad if you will give the corporal any information you can. Besides this, I wish you and the other citizens on the Belle Fourche would inform me at once if you hear of any Indians approaching your neighborhood.

If you have time I would like to see you in my camp.On this day, December 19th, later in the day, intelligence reached me from detachment sent down the river to look after Standing Rock Indians, that the Cheyenne River Indians had stopped on their way to Bennett, and had assembled at Hump’s Camp to meet Sitting Bull Indians. (See dispatch to division and department headquarters, dated December 19th.):

Sumner to Miles and Ruger (Dec 19): It is reported to me just now by scouts that Sitting Bull Indians are coming in to mouth of Cherry Creek, on the Cheyenne, and all the Cheyenne River Indians down as far as Cherry Creek have assembled at Hump’s camp to meet the Sitting Bull Indians, and scouts report that they are defiant. I send one troop of cavalry in advance in that direction and will follow with the other two troops and a company of infantry in an hour. Would like to have infantry from Bennett hurry along.

On receiving this information from the officer in advance, Lieut. Duff, Eighth Cavalry, I marched at once down the river with two troops cavalry and one company of infantry, reinforced to fifty men and two Hotchkiss guns, and was soon in support of the troop, Godwin’s Eighth Cavalry, near Big Foot’s camp. On December 20th reached Narseilles ranch and went into camp, and there received a letter from Big Foot stating that he was my friend and wished to talk. December 21st, made an early start to join Godwin’s command, and to either fight or capture Big Foot if any resistance was offered. While on the march, and 4 miles east of Narseilles, Big Foot came to me, bringing with him two Standing Rock Indians. He expressed a desire to comply with any orders I had to give, and said all his men would do the same. I asked at once how many Indians were in his camp. He replied 100 of his own and 38 Standing Rock Indians. I asked why he had received the latter, knowing them to be off their reservation and refugees. His reply was certainly human, if not a sufficient excuse, and was to the effect that they were brothers and relations; that they had come to him and his people almost naked, were hungry, footsore, and weary; that he had taken them in, had fed them, and no one with any heart could do any less. The Standing Rock Indians with Big Foot, that is, those whom I saw, answered his description perfectly, and were, in fact, so pitiable a sight that I at once dropped all thought of their being hostile or even worthy of capture. Still my instructions were to take them, and I intended doing so. Since the flight of Big Foot and the fight on Wounded Knee, I believe I was to some extent imposed upon in regard to Standing Rock Indians, and I now think there were perhaps some warriors with them who were kept out of sight, but near enough to get food and to act in support should a fight take place.

However, everything went on quietly and I was not aware of it if any other Indians than those in sight were near us. I directed Capt. Hennissee, Eighth Cavalry, to go to the Indian camp with Big Foot, get all the Indians and return to my camp at Narseilles ranch, where I encamped on the night of the 21st. Godwin’s troop was recalled and at 3 p.m. Hennissee marched in with 333 Indians; the increase in numbers as given by Big Foot to me on the road being something of a surprise. I arranged my camp accordingly and was fully prepared for anything that might occur. The Indians went into camp as I directed, turned out their ponies and made themselves comfortable while preparing for the feast I had promised. The night passed quietly and on the morning of the 22d we all made an early start for my home camp, Big Foot at the time seeming willing to go there. On the march some of the young bucks undertook to pass the advance guard, and Lieut. Duff, the officer in charge, drove them back, and in so doing deployed a line faced to the rear. This action seemed to frighten some of the Indians, and the squaws in the wagons whipped up, threw out some of their loads and screamed, and this excitement was soon communicated down the column. I rode at once to the head, found Big Foot, who was driving his wagon, and asked him what this excitement meant. He laughed and in reply said—Nothing the matter, some old women screamed. I told him to have it stopped, and he at once got on his pony, rode about and allayed all confusion, and the march continued to the village.

I will here introduce copies of my dispatches sent to division and department commanders on the 19th, 21st, and 22d December, [The dispatch dated the 19th was presented in the previous block quote. Following are two dispatches dated the 21st and two dated the 22nd]:

Sumner to Miles (Dec 21): Your dispatch received at 12 o’clock last night. Sitting Bull Indians are in Big Foot’s camp, 3 or four miles in front of my advance. Big Foot sent me word last night that he heard I was coming with all the soldiers and that he wanted to talk. I hope to-day to get the surrender of Big Foot and all the Indians, including the Sitting Bull Indians. All the Indians on Cheyenne River and Cherry Creek have gone to Bennett, I understand. I intend moving on Big Foot’s camp immediately, and will let you know the result. If successful, will move back to my supplies in the old camp with the Indians.

—–

Sumner to Miles (Dec 21): On the march to Big Foot’s camp this morning met him and several Standing Rock Indians. They were willing to do anything I wish. I ordered them back to their camp and sent a troop of cavalry with them to pack up their stuff and to come into my camp at Narseilles’s ranch this evening. To-morrow I will take the whole crowd, probably 150, to my home camp, and, unless otherwise ordered, will send them to Fort Meade. One of the stipulations was something to eat, and I have ordered fresh beef and will give them rations. This clears up all Indians on Cheyenne River as far as Cherry Creek, and if any other Standing Rock Indians are out they must be few.

The day after this report General Miles telegraphed the Adjutant General of the Army, “Colonel Sumner reports the capture of Big Foot’s band of Sioux to-day, numbering about one hundred and fifty. He has been one of the most defiant and threatening.” General Ruger similarly reported, “Big Foot, with his following, including some Sitting Bull fugitives… surrendered yesterday to Col. Sumner.” What Sumner did not include in his report was another message that General Ruger included in a December 27 report, in which Ruger quotes Sumner as transmitting two hours after the previous message, “Indians have all surrendered and will bring them in to-morrow.”[11]

Colonel Sumner’s report continues:

Sumner to Miles and Ruger (Dec 22): In accordance with agreement which I telegraphed you yesterday, Big Foot, all the Cheyenne River, and Standing Rock Indians came into my camp at 4 p.m. yesterday; they number 333 Indians, 51 wagons, and a herd of ponies. There are 38 Standing Rock Indians in all, and among the Cheyenne River Indians about 30 young warriors, said to be well armed, although I have seen no arms so far. I am holding on to and feeding the crowd, to prevent, if possible, these young men from going south. I will march in a few moments for my home camp with the whole outfit, and expect to reach there this evening. Rations should be supplied me at once if it is expected that I retain these Indians any length of time, and instructions requested as to final disposition.

—–

Sumner to Miles (Dec 22): Did not succeed in getting the Indians to come into my camp on account of want of shelter for women and children. Did not feel authorized to compel them by force to leave their reservation.

Standing Rock Indians are at Big Foot’s village, with their friends, and Big Foot has agreed to hold them there or bring them here, either. They seem a harmless lot, principally women and children. There is no danger of their going towards the Bad Lands, having very little transportation.In that of the 19th, I state Indians were reported to me as defiant. That report was false, and I did not find them to be so. In dispatch [dated the 21st], I used the term surrender more in anticipation of what might have taken place.

When the meeting took place there seemed to be no occasion for surrender, and in all later dispatches I relate the fact that the Indians “come in,” and all statements in those dispatches are based on the supposition that I had only to deal with 138 Indians, whereas the number coming in was 333. Still, as will be observed in dispatch [dated the 22d], I hoped to carry out my designs with even that number, but on arrival at the village I saw that Big Foot himself could not control or overcome the desire they all had to go to their homes, and he came frankly to me and said: “I will go with you to your camp, but there will be trouble in trying to force these women and children, cold and hungry as they are, away from their homes.” And further said: “This is their home, where the Government has ordered them to stay, and none of my people have committed a single act requiring their removal by force.” I concluded that one of two things must happen—I must either consent to their going into their village or bring on a fight; and, if the latter, must be the aggressor, and, if the aggressor, what possible reason could I produce for making an attack on peaceable, quiet Indians on their reservation and at their homes, killing perhaps many of them, and offering, without any justification, the lives of many officers and enlisted men. I confess that my ambition was very great, but it was not sufficient to justify me in making an unprovoked attack on those Indians at that time, and even if an attack had been made to enforce my wishes, the result would have only been to have driven the Indians out of the country sooner than they did go. I was prepared to fight at any moment should provocation be afforded, but with my small force I could not have surrounded the Indians, nor could I have prevented their fleeing from me and going to the Bad Lands, or even to the hostile camp, with a reasonable demand for protection, which, in going as they did, they did not have. [The first dispatch dated the 22d] indicates the fear I had of a sudden departure of the young men in a stealthy manner. I considered that Big Foot’s presence and influence with them would be more powerful to prevent that than anything I could do; he was, as it were, working with me to accomplish my ends, and I had every confidence that he would be able to hold his people on the reservation, and also to deliver the Standing Rock Indians to me as he promised to do, and as I still believed he desired to do. It was not practicable at that moment to select the 38 Standing Rock Indians out of the crowd, as no one but the Indians themselves knew who they were. I therefore, for the reasons stated, left Big Foot with his people, and in connection with such action I believe I was acting in accordance with many precedents of early timers of later years, and with those established at Pine Ridge in the present campaign, where, even in the presence of a much larger force proportionately than I had, Indians were frequently allowed to be friendly one day and hostile the next, and then to return to a friendly status. It is fair to presume that those Indians who surrounded and fired upon the Seventh Cavalry December 30 came from the hostile camp and returned to it again. Leaving Big Foot, then, with his people in his village, but taking his promise to see me next day and bring with him the Standing Rock Indians, I returned to my camp, and purposely all the way there, to establish confidence, after the excitement on the march, which might have been continued, or perhaps increased, had I encamped and taken up an offensive position near the village, but which was no doubt allayed by my apparent reliance on the chief, whom I was bound at that time either to support or fight. Up to that time I had no reason to doubt the integrity of the chief; on the other hand, had every reason to believe in the sincerity of his motives. I decided to trust him, and in doing so was wholly unmindful of orders received, and desirous only of accomplishing what I understood to be the wishes of my superiors, especially those of the division commander, believing that his plans were to settle matters, if possible, without bloodshed. I have already stated what, in my opinion, would have occurred if I had taken the other course. While in my camp on the night of the 22d and 23d, I received the [following] dispatch from Gen. Miles:Chief Big Foot, or Sitanka, was about 64 years of age and a Miniconjou Lakota from the Cheyenne River Reservation. He was known among his people as a traditionalist and a peacemaker and had earlier in life been known as Spotted Elk, or Oh-Pong-Ge-Le-Skah. He was photographed in 1888 as a member of a Cheyenne River delegation to Washington, D.C., and is pictured above on the right with a peace pipe in his lap.[12]

Miles to Commanding Officer, Fort Meade (Dec 22): The following to be sent to Col. Sumner at once, without delay: A report comes from Minnesela that several hundred Indians near Camp Crook, near the Little Missouri, not far from Cave Hills, at head of North Fork of Grand River. The report comes from citizens, who state that 2 scouts with a command in their vicinity moving south had encountered Indians, and that the 2 scouts were notifying citizens. No report has been received of that number of Indians being absent and it does not agree with our official report; still there may be something in it. I think you had better push on rapidly with your prisoners to Meade, and be careful that they do not escape, and look out for other Indians. When will you be at Meade? I will send you orders through that place.

I had no thought of escape of the Indians as a body, but was only anxious lest a few warriors should run away, and I supposed I had taken the best precautions against that and was therefore obeying orders. The information relative to Indians from the north made me hesitate to leave my camp at all, but I hoped to accomplish matters with Big Foot on the 23d—get him started for Bennett and hurry back to camp, although I marched towards the village with every soldier I could take, and fully intended to enforce my orders for Bennett and make any refusal sufficient provocation to fight, and in that extremity take the chances on the call to Meade. My anxiety at this time to meet all the calls made upon me is apparent in [the following] dispatches to Gen. Miles dated 22d and 23d:

Sumner to Miles (Dec 22): Have received your dispatch of the 22d. Suppose you have received mine of this date stating the Indians would not be in until to-morrow. In view of the importance of your dispatch, shall I wait for them or march at once for Fort Meade? It would be very hazardous to leave this country unprotected just now. I can reach Fort Meade with my command in thirty hours from here, but will await further orders.

—–

Sumner to Miles (Dec 23): If the new complication from the north does not amount to anything, and if Big Foot does not keep his promise and come in to-day with those people, I think I will have temporized with him to keep peace long enough, and would like to go down and capture his village. He has heavy log buildings admirably situated for defense, and I would like a couple of guns sent out from Meade for this purpose and Capt. Rodney to take charge of them. Please answer.

At noon on the 23d December, not hearing anything from Big Foot or from any of my scouts who had been sent to the village, I had ordered the march of my command and was about moving when Mr. Dunn, a citizen living on Belle Fourche and friend of Big Foot’s, appeared at my camp. I obtained Mr. Dunn’s service to go to the village and see what was going on, and instructed him to take my order to Big Foot to go with his people to Bennett, and also to say to Big Foot that I would enforce the order. What Mr. Dunn said or did is a question—his statement and others are hereto attached [to be presented in a later post].

I was at one time inclined to believe that Mr. Dunn had played me false, but he is a man of good reputation, and from his statement and statements of officers who have seen and interviewed him since, I am now sure that I did him an injustice, and I do not believe or claim that Mr. Dunn was in any way responsible for events which afterwards occurred. Mr. Dunn, after seeing Big Foot, met me on the march and informed me that Big Foot and all his people had consented to go to Bennett—that there was a good feeling among them—no desire to fight or in any way to oppose my orders, and that they would move next morning. Big Foot intended to visit my camp that evening. I had no suspicion, nor had anyone else in my command, that anything else would happen. This record shows what confidence I already had in Big Foot, and certainly Mr. Dunn’s report was not calculated to weaken it; besides this I had a still later report from my interpreter, Benoit, who left the village after Dunn, that everything was all right and everybody going to Bennett. About 7 p.m. two scouts came in, one stating that although they were going up Deep Creek, he thought they would turn towards Bennett after reaching the divide, and that they did this to escape the soldiers coming up the Cheyenne River from Bennett. On the possibility that they had gone south I sent the [following] dispatch to Col. Carr, Sixth Cavalry:

Sumner to Carr (Dec. 24.): Big Foot did not come into my camp to-day as promised, and I started for him this afternoon. His lookouts, of course, let him know that I was on the road. He sent me word by messenger that he would go to Fort Bennett to-morrow with all his people, but when I approached his village I found it vacant, and my scouts have informed me that he has gone up Deep Creek Trail, due south; that he will probably pass Mexican Ed’s and head of Bull Creek near the Bad Lands. If you can move out to-morrow morning (a force) you will doubtless intercept him. They had yesterday 100 fighting men, and about 300 altogether, women and children. They started from here in very light order; no wagons; all had ponies, and will travel very fast. For fear they may return here I will stay here to-night, scout up Deep Creek to-morrow, and if I hear nothing, will march for Smithville and go out Bull Creek towards Bad Lands.

Dispatches from General Miles relative to Indians coming from the north and west of me in considerable numbers prevent my following the trail and getting out of reach. I hope you will get this in time and you will head them off.Also dispatch to Gen. Miles and Ruger:

Sumner to Miles and Ruger (Dec 23): Big Foot sent me word that he would go to Bennett with his people to-morrow. I marched down here to his village and found that he had started south in very light order, with ponies and lodge poles; no wagons. From your last dispatch in regard to going to Fort Meade to meet Indians said to be coming from the north, I feared to leave this vicinity in pursuit of Big Foot, but have sent couriers to Gen. Carr, which ought to reach him by daylight in the morning. If Carr pushes a force from his camp promptly to-morrow eastward he will have plenty of time to intercept him. Besides this, Big Foot might elude me, and return and commit depredations on the Belle Fourche. For reasons given I will remain subject to further information from you, and be ready to march in any direction.

On the morning of December 24, I received dispatch from Gen. Miles dated 23d, copy herewith:

Maus to Sumner (Dec 23): Report about hostile Indians near Little Missouri not believed. The attitude of Big Foot has been defiant and hostile, and you are authorized to arrest him or any of his people and to take them to Meade or Bennett. There are some 30 young warriors that run away from Hump’s camp without authority, and if an opportunity is given they will undoubtedly join those in the Bad Lands. The Standing Rock Indians also have no right to be there and they should be arrested. The division commander directs, therefore, that you secure Big Foot and the 20 Cheyenne River Indians, and the Standing Rock Indians, and if necessary round up the whole camp and disarm them, and take them to Fort Meade or Bennett.

Col. Merriam is moving up the Cheyenne River, and if he joins you turn this order over to him, with instructions to use both commands, and for him to take such force as may be needed to take the Indians to Fort Bennett or Fort Meade. On the completion of this duty your command will move down and extend Col. Carr’s line. By command of Gen. Miles.It will be observed that in this dispatch Big Foot is considered both hostile and defiant by the division commander, and that positive orders were sent me for action against him, but those orders came too late and could not be carried out.

The opinion of the division commander was quite the reverse of my own experience with these Indians and I may therefore be reasonably excused for not anticipating such orders, and with the exception of the dispatch from Gen. Ruger, indicating the desirability of arresting Big Foot, it will be difficult to find in any of my orders or instructions any intimation of hostility on the part of those Indians. On the other hand all anxiety seemed to point to my preventing their becoming hostile. I believe that duty was best performed in the course pursued up to the time they left their reservation, an event I did not look for, could not anticipate, and could not have prevented. Any move on my part to the south of Big Foot’s village would have left the settlements unguarded, the citizens unprotected, who were by orders under my protection, and my supply camp on the river at the disposal of the Indians on their way south by that route instead of the one they took. If Big Foot had been hostile and defiant in attitude I was not aware of it until receiving the orders making him so and authorizing his arrest and the arrest of others. My course would have been very plain if I could have received these orders in time, or could have known the wishes of the division commander. The result, however, would probably have been the same, as any display of hostile intent on my part would have caused the Indians to flee, and I could not have interposed any force to prevent. The fact that even in the opinion of my superiors I did not have sufficient force to do that is, I believe, made apparent in several dispatches from department headquarters stating that I would be reinforced first by Wells’ command, then by Fechét’s command, then by Adams’s First Cavalry and Cheyenne scouts, then by Col. Merriam, Seventh Infantry, none of whom ever reached me in time; also in several of my dispatches are reports that I did not have force enough to guard the trails leading south. I did not ask for more troops or for any reinforcements.

I never for a moment considered that my command was not strong enough to meet any force likely to be brought against it, but that is quite a different matter from surrounding and capturing an enemy, especially of the character of the Indian, who considers a surrender merely a halt in the fight to be fed, but had no idea of being disarmed. In the case of Big Foot’s band now under consideration no surrender was made, no arms were demanded. The march to the vicinity of Big Foot‘s camp, situated down the Cheyenne River 22 miles below his village, was for the purpose of arresting any warriors from the Standing Rock Agency who were supposed to have been concerned in the Sitting Bull fight, and who, it was feared, might go further south, to have a check on Big Foot’s band and other Cheyenne River Indians. As I already stated, the mere appearance of the few Standing Rock Indians in sight, as reported, precluded anything like the use of military force against them. The Big Foot band and other Indians belonging to Cheyenne River were on their reservation and willing to go to their village in compliance with my wishes. This was a complete surrender as far as I was authorized to act; any further demand on my part would have provoked hostilities and would have placed me clearly outside of my orders, and even beyond any excuse for such action. Nor could it be presumed that an attack by my force on Big Foot would have resulted in any other way than that experienced by every commander in our service who has made such an attack. The Modocs were attacked and fled to the lava beds, killing every citizen within reach. The Bannocks were attacked and scattered over the country, killing innocent people and committing depredations. The Nez Percés were attacked by Gen. Howard and led his command and others for thousands of miles, and when finally surrounded and attacked by fresh troops a number succeeded in escaping to Canada. In the ’76 campaign on one occasion the Indians were met in hostile array and the troops were withdrawn, and it is supposed the commanders, having discretion, did a wise thing. In the campaign of this year, at Pine Ridge, it is the common rumor, and generally supposed to be true, that Two Strikes’ band and other bands of Indians were allowed to pass back and forth between the agency and the hostile camp, always armed and alternately friendly and hostile, at their own will. I do not presume to question the management of these affairs or the wisdom of the policy pursued, but in connection with that management and policy I would like to have my action considered. My orders were positive to prevent the escape of the Indians I had in charge; to prevent any Indians from coming from the south to join those on the Cheyenne River; to protect the settlements in my rear and on the Belle Fourche, and to watch for Indians coming from the northwest (that was in my rear), and to be prepared to march rapidly for Fort Meade. In the face of these several duties, all to be performed by my small command, I could only hope to succeed by using a peaceful policy rather than force.

I hoped to hold Big Foot, and that he would be able to control his men and take them to Bennett, and up to 7 p.m. on the night of the 23d I felt reasonably assured that I would not only succeed in that measure but I would also be prepared for any other demands. So that, instead of being in disobedience of orders, as reported by the division commander, I was, I know, doing my utmost to carry out his orders and even to fulfill what I thought were his wishes. The flight of Big Foot’s band, no doubt, interfered with the plans of the campaign; I was prepared to hear that, and further, perhaps, that I had not met with the expectations of the major-general commanding in permitting the Indians to go. I should have regretted even that censure, but to see that I am accused of disobedience of orders is a surprise to me, and, in my opinion, is as unjust as it is unwarranted either by facts, circumstances, or a possibility of intention. My orders from Gen. Miles, after the flight of the Indians for Pine Ridge, were to return to my camp and remain in that vicinity. (See following dispatch dated December 24.):

Miles to Sumner (Dec 24): The reports of Indians up north are false. I can not understand your telegram of 22d, stating that Big Foot’s band and Indians to number 330 had surrendered, and you would march in a few moments with them to your home camp. Col. Merriam had orders to march up till he joins you, unless he had found you had taken Big Foot’s band to Fort Meade. Endeavor to communicate with him at once. You have two Hotchkiss guns and over 200 men, which certainly ought to be enough to handle 100 warriors in any place. Those Standing Rock Indians, the 30 Cheyenne River Indians, and Big Foot and his immediate followers should all be arrested, disarmed, and held until further orders. Big Foot has been defiant both to the troops and to the authorities, and is now harboring outlaws and renegades from other bands. Turn this over to Col. Merriam should he join you.

—–

Miles to Sumner (Dec 24): Your orders were positive, and you have missed your opportunity, but such does not often occur. Endeavor to be more successful next time. Hold your command in that vicinity, but in close communication with Fort Meade, and be prepared to intercept any body of Indians that may escape from the troops south. Communicate with Col. Merriam, and notify him he is directed to join you.

Since the departure of the Indians I have learned through other Indians that Big Foot was forced to go with his people; that there was probably no intention of hostilities, but rather a desire on the part of all to seek the crowd at Pine Ridge Agency, and being there to get better terms than at Bennett. My opinion is that the advance of Col. Merriam up Cheyenne River and the report that the Standing Rock Indians at Bennett had been disarmed caused a sudden change of plan in Big Foot’s village, and that the young men, on account of the situation, were able to overcome all objections to going south. They certainly passed through the country without committing any depredation or harming any one.

They passed near a detachment from my command at Davidson’s ranch on head of Deep Creek; passed within sight of citizens at Pinaugh’s ranch; at Howard’s went through his pasture filled with horses and cattle and it is reported disturbed nothing. They had passed all roads, as I understood it, to the hostile camp, and were met by Maj. Whitside 12 miles from the agency and going in that direction; were willing to surrender to him and did march with him to his camp and remain quietly with him all night. This command having, as was reported, captured Big Foot’s band, was as large, if not greater, than mine, and was within supporting distance of other troops. Still Maj. Whitside asked for reinforcements and they were promptly sent, as he reported he had not considered it safe to make the attempt to disarm them with his command. Reinforcements having arrived, this band of Indians was then in the presence of regimental headquarters, eight troops cavalry, and three or four guns with artillery detachments; a fight occurred, the details of which have been published and have no place here except to show that any attack by my command, although without provocation, would, if successful, have driven the Indians out of the country, but could not have held or disarmed them.

It will be observed from the evidence accompanying this report that on the day on which the major-general commanding was writing his dispatch [dated] December 23, proclaiming Big Foot to be hostile and defiant and ordering his arrest, he (Big Foot) was in reality quietly occupying his village with his people amenable to orders, having given no provocation whatever to my knowledge for attack, and no more deserving punishment than peaceable Indians at any time on their reservation. I was not aware that Big Foot or his people were considered hostile, and am now at a loss to understand why they were so considered, every act of theirs being within my experience directly to the contrary, and reports made by me were to the effect that the Indians were friendly and quiet.

Respectfully submitted.

E. V. Sumner, Lieutenant-Colonel Eighth Cavalry.

From the official record it may appear that Lieutenant Colonel Sumner’s report was sufficient in allaying any concerns that General Miles or General Ruger may have had, as no charges for disobeying orders were filed against the cavalry officer. However, buried in the Nelson A. Miles papers at the Military History Institute at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, is a confidential report from General Miles’s headquarters that appears to have never been filed with the War Department. Dated March 4, 1891, on the letter head of the Headquarters Division of the Missouri at Chicago, Illinois, the letter expresses Miles’s unchanged opinion of Colonel Sumner’s actions regarding the capture and escape of Big Foot and his band of Miniconjou Lakota.

(Click to enlarge) First page of Major General Nelson A. Miles’s personal censure of Lieutenant Colonel Edwin V. Sumner. The orignal document is unsigned and shows no markings indicating that it was ever sent outside of Miles’s own headquarters.[13]

Up to the date of Big Foot’s capture, December 21st, 1890, Colonel Sumner seems to have acted with great discretion. To have accomplished the capture of this chief and his following without loss of life was very commendable, and the wishes of his superiors so far had been accomplished, and all danger of further trouble from these Indians was assured when Colonel Sumner reported that he had Big Foot and his people prisoners, and made it possible to utilize Colonel Sumner’s command at other points to great advantage, but all this was more than counterbalanced by subsequent events. Big Foot once a prisoner should not have been allowed to escape, and under the orders or expressed desire of his superiors, Colonel Sumner should have prevented such escape by using his entire command effectively. It appears that this was not done, but instead, after the Indians had surrendered, and had been marched some distance under guard of the troops, they were allowed to go wherever they wished without guard, and the troops were marched several miles distant from that place to camp. This was certainly not in compliance with the letter or spirit of General Ruger’s instructions, to wit: in case of his arrest, he will be securely guarded and sent to Fort Meade. To say the least, this was very poor judgment on Colonel Sumner’s part. Once in his power,

he(Big Foot) should not have been allowed to escape.

His(Col. Sumner’s) action in this case brought about a most serious complication of affairs in other parts of the field of operations, by making it possible for the entire hostile element to effect a concentration, and necessitated the using of nearly the entire mounted force of troops in the field to accomplishthe thing(and not without great loss of life), and what wasfully(so completely ) within the grasp of Colonel Sumner, without bloodshed.

Edwin V. Sumner was promoted to colonel in 1894 when he succeeded Colonel James W. Forsyth as the commander of the 7th Cavalry Regiment. Sumner served as a brigadier general in the U.S. Volunteers during the Spanish-American War when he commanded the Department of the Missouri. He was promoted to brigadier general in the regular army at the end of March 1899 and retired three days later.

Brigadier General Edwin V. Sumner, Jr., died on August 23, 1912, at the age of seventy-seven. He was buried next to his wife in the United States Military Academy Post Cemetery at West Point, New York.[14]

Endnotes:

[1] Adjutant General’s Office, Official Army Register for 1891 (Washington: 1891), 75 and 298.

[2] Argalus G. Hennisee, “Post Return of Camp on Cheyenne River, S. Dak., commanded by Captain A. G. Hennisee, 8th Cavalry, for the month of April 1890,” National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington, D.C.; Returns from U.S. Military Posts, 1800-1916, Microfilm Serial: M617, Microfilm Roll: 1502, Military Place: Cheyenne River S Dak, Return Period: Apr 1890. Hereafter cited as Hennisee, Camp Cheyenne Post Return.

[3] William F. Kelley, Pine Ridge 1890: An Eye Witness Account of the Events Surrounding the Fighting at Wounded Knee, edited and compiled by Alexander Kelley & Pierre Bovis (San Francisco: Pierre Bovis, 1971), cropped from fold out map attached to back of book. Hereafter cited as Brooke Campaign Map.

[4] Hennisee, Camp Cheyenne Post Return.

[5] John C. H. Grabill, photo., “At the Dance. Part of the 8th U.S. Cavalry and 3rd Infantry at the Great Indian Grass Dance on Reservation. Photo and copyright by Grabill, ’90,” Collection: Grabill Collection, Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C., Call Number: LOT 3076-2, no. 3564, (http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/99613793/), accessed 11 Mar 2017.

[6] “Campfire Stories. After Thirty Years. Eventful Life of a Faithful Soldier Who Retires on a Pension,” Williston Graphic, Williston, N.D., Nov 8, 1906, 3.

[7] United States Congress, “Letter from The Secretary of the Interior, 11 December 1890, page 4, from The Executive Documents of the Senate of the United States for the Second Session of the Fifty-first Congress. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891).

[8] Ibid.

[9] Brook Campaign Map, with inset.

[10] Sumner Jr., Edwin Vose, Exhibit H to Brig. Gen. Thomas H. Ruger’s “Report of Operations Relative to the Sioux Indians in 1890 and 1891,.” in Report of the Secretary of War; being part of the Message and Documents Communicated to the Two Houses of Congress at the beginning of the First Session of the Fifty-Second Congress, vol. 1, by Redfield Proctor (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1892), 223-235.

[11] National Archives Microfilm Publications, “Reports and Correspondence Related to the Army Investigations of the Battle at Wounded Knee and to the Sioux Campaign of 1890–1891.” (Washington: The National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration, 1975),757-763, 604, 605, and 628.

[12] Smithsonian Institution Research Information System (SIRIS), repos., “Cheyenne River Delegation, 1888,” BAE GN SI 5737, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution (http://siris-archives.si.edu/ipac20/ipac.jsp?&profile=all&source=~!siarchives&uri=full=3100001~!248682~!0#focus), accessed 11 Mar 2017.

[13] Samuel L. Russell, photo., Nelson A. Miles Papers, Sioux War, 1890-1891, Wounded Knee, Pullman Strike, Commanding General, Box 4 of 10, US Army Military History Institute, Carlisle, PA.

[14] Russ Dodge, photo., “Edwin Vose Sumner, Jr,” FindAGrave (https://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=4912), uploaded 20 Oct 2000, accessed 11 Mar 2017.

Citation for this article: Samuel L. Russell, “Lieutenant Colonel Edwin V. Sumner Jr. and the Flight of Big Foot’s Band,” Army at Wounded Knee (Carlisle, PA: Russell Martial Research, 2015-2017, http://wp.me/p3NoJy-1kr) updated 3 Nov 2018, accessed date __________.

Sam;

After reading your latest article I must ask you this. Do you still feel it was a justifiable act on the part of the Army to round up and provoke Big Foot’s band in what seemingly was a needless battle at Wounded Knee Creek? Was General Miles correct after all in going after Colonel Forsyth and relieving him of his command? It seems that the units of the 7th were at least in part, poorly led, and much to “Hot to Trott” after Big Foot’s Band . As usual I look forward to these articles on the Wounded Knee Battle that you present so well. Thank you, Lawrence F. Nirenberg

LikeLike

Mr. Nirenberg… “Justifiable act on the part of the Army to round up and provoke,” interesting interpretation of my posts, but not a position I hold. All of my research is an attempt to make these events more understandable. This report certainly makes it all the more tragic. Sumner’s report is interesting because it runs contrary to most of the officers’ and soldiers’ perspectives. It was written with the purpose of convincing his superiors that he did not disobey orders. He left out, either conveniently or inadvertently (I believe it was the former) the message he sent to Brig. Gen. Ruger on 22 Dec in which he stated “Indians have all surrendered and will bring them in to-morrow.” Makes me wonder what else he failed to include.

Decision making based on military intelligence is more art than science, as a commander is taking often conflicting information from multiple sources and making a judgment on what is correct, what it indicates an adversary may do in the future, and deciding how and when to commit forces to affect the results that will ultimately achieve tactical and strategic victory. That is far more difficult than historically analyzing events a century after they occurred and assuming to know better what commanders should have known and should have done. General Miles certainly was receiving conflicting intelligence on Big Foot’s actions and intentions, and the correspondence sent by Sumner as events unfolded seem to conflict at times. I would think a military commander would weigh heavy the observations of the commander on the ground that has observed and interacted with a potential adversary. Captain Hennisee would have been an exceptional source of information, as he had been commanding the camp on the Cheyenne River since April 1890. Unfortunately, I have found little from that officer other than the first Post Return quoted above. I would also expect a military commander to weigh heavily the opinion of the Indian Agent at the location, who presumably was also interacting regularly with the Indians on the Cheyenne River. Ultimately, General Miles, in the latter part of December, gave more weight to the intelligence received from Agent Palmer than the at times conflicting information from Colonel Sumner.

Interestingly, I just came across an article published in 1906, in which one of the infantry soldiers stationed at Camp Cheyenne in 1890 described hostile, or at least adversarial, actions by Big Foot’s band.

Source: “Campfire Stories. After Thirty Years. Eventful Life of a Faithful Soldier Who Retires on a Pension,” Williston Graphic, Williston, N.D., Nov 8, 1906, 3 (http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn88076270/1906-11-08/ed-1/seq-3/) accessed 12 Mar 2017.

LikeLike

Sam, when you have time let’s chat…”every act of theirs being within my experience…” is instructive. The racism of the time being what it was and the expectations of those “in charge” of ensuring the transition of “the savage to the man” is most telling.

The NODAPL movement is just a continuance.

Go Army! Beat Navy!

Regards, Rod…

Rodney G. Thomas | Colonel, U.S. Army, Retired |

Amazon Author’s Page – http://www.amazon.com/-/e/B01G42WOEW

Rubbing Out Long Hair – Pehin Hanska Kasota: The American Indian Story of the Little Big Horn in Art and Word. The 2010 Custer Battlefield Historical & Museum Association G. Joseph Sills Jr. Book Award

LikeLiked by 1 person

This article was originally posted on 11 Mar 2017. I updated it today, adding Maj. Gen. Miles’s unsigned confidential letter of censure of Lieut. Col. Sumner’s actions regarding the capture and subsequent escape of Big Foot.

LikeLike