The gallantry of officers and soldiers in the action at Wounded Knee is worthy of the highest praise. Women and children were killed and wounded, but this could not be avoided under the circumstances.

By the fall of 1890 Brigadier General John R. Brooke had been in command of the Department of the Platte for two and a half years. He was a portly fifty-two-year-old infantry officer. As a young man Brooke had accepted a commission as a Captain in the 4th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry in 1861 and served continuously through the war ending as a Brigadier General, U.S. Volunteers. Brooke was awarded brevet promotions for gallant and meritorious services at the battles at Gettysburg, Spottsylvania Court House, and Cold Harbor. He resigned his volunteer commission in 1866 to accept a regular commission as a Lieutenant Colonel in the 37th U.S. Infantry Regiment. Most of his service since 1869 had been in the frontier west as a Lieutenant Colonel and later Colonel of the 3rd Infantry before being promoted to Brigadier General in April 1888 and taking command of his department.[1]

The Department of the Platte included the states of Iowa, Nebraska, and Wyoming, the territory of Utah and most of Idaho. At the outset of the campaign, Major General Nelson A. Miles placed General Brooke in command of forces in the field at the Pine Ridge and Rosebud Agencies near the southern border of South Dakota. Both agencies lay within the boundaries of General Thomas Ruger’s Department of Dakota. This caused confusion in command and reporting channels several times during the campaign. Brigadier Generals Ruger and Brooke were peers and direct subordinates of Major General Miles. Both reported to his headquarters. However, General Brooke’s placement inside of General Ruger’s department left open the question of whether Brooke would take orders and guidance from and report through General Ruger. General Miles’s adjutant general tried to clarify the command relationship in a telegram to Ruger on 23 November, but likely only added to the confusion.

In order that you may fully understand the situation, while you were engaged in the important duties of attending to the Indians on the reservations north of Rosebud and Pine Ridge, the appeals of the agents for protection of life and property at those two agencies were so urgent and the condition of the Indians so threatening that the Division Commander ordered troops sent there at once, and directed General Brooke to go, as he also had command of the troops sent there and in his Department, made available to use them if necessary. That brought him within your Dept. where he now is, and of course under your command for such directions as may be necessary to give within your Department.

The Division Commander does not anticipate any friction or conflict of authority, and is well satisfied with the action of both yourself and General Brooke. Copy of this will be sent to General Brooke in order that he may fully understand the situation. The Division Commander expects all to work in harmony for the one object of preventing an Indian outbreak, or suppressing it quickly if one should occur.[2]

Ruger and Brooke did cooperate harmoniously with little friction between the two, but on several occasions Brooke reported information to Ruger that Miles thought should have been reported immediately to himself. Reporting from Brooke certainly caused friction with General Miles with the latter General occasionally receiving more detailed information through newspaper reports rather from his subordinate. On 7 December General Miles telegraphed, “Newspaper accounts from Pine Ridge report council between yourselves and Indians, and represent that the matter was being managed by other parties than yourself, and seemed to indicate that you were not the master of the situation at that place.” Miles continued, “Correspondence also report large number of depredations have been committed by these same Indians, also the capture and destruction of the government herd belonging to the agent. No official report of this has been received.” General Brooke took the message as a chastisement and responded within the hour, “I cannot be responsible for the newspaper statements. All depredations were reported to you except possibly about the beef herd, which may not have been mentioned specially and which has not been destroyed…. I do not think I have in any way exceeded the power placed in my hands. I have used my best judgment and have not only carried out the order of the President but have obeyed yours.” Brooke closed with, “I have done nothing to call forth the censure conveyed in your dispatch.” General Miles, on this and several more occasions, walked back his admonishment and tried to smooth ruffled feathers, “Your telegram received and am somewhat surprised that you should have interpreted mine of this morning as in any sense conveying censure. No such purpose was intended.”[3]

Brooke’s occasional failure–intentional or not–to report timely and accurate information to General Miles evoked his superior’s ire on the most critical day of the campaign, 29 December, the evening following the fight at Wounded Knee. General Brooke reported to General Ruger detailed information regarding the 7th Cavalry’s fight that day and the extent of their casualties but failed to render the report to General Miles. Again, the Division Commander learned of the large number of killed and wounded from news reports the next day. He fired off another angry telegram to Brooke, “I hear that twenty-five men were killed and thirty-four wounded in fight with Seventh Cavalry. Some one seems to be suppressing facts.” Likely Miles thought that that “some one” was Brooke, and upon his (Miles) arrival at Pine Ridge the following day, he immediately ordered his subordinate to take the field for the duration of the campaign. As General Brooke and staff marched out of the Pine Ridge Agency toward White River, General Miles sent a sarcastic message, “I hope you will see that the troops are in position with as little delay as possible, as it is a fine day for marching, and accept my best wishes for the best results and a very happy New Year.”[4]

Newspapers rightly took note of the slight, reporting that General Brooke had been relieved. Regarding Brooke’s departure from the agency, the Omaha Bee stated, “From the expression upon the faces of the officers and men, as they pulled out through the snow and bitter cold, it was evident that they didn’t relish General Miles’ order that came like the sharp crack of a whip.” General Miles’s staff had to address in the press the false rumor of General Brooke being relieved, “Captain Higgins [sic: Eli L. Huggins was Miles’s senior aide-de-camp] discredited the report, saying it was the natural order of events that General Miles, being the superior officer, should on his arrival at Pine Ridge assume command.”[5] Throughout the campaign General Brooke was sensitive to the criticism he received in the press. As the campaign was winding down General Brooke became exasperated with the negative reporting and sent the following message to General Miles:

General: There is little in this life to an officer but the dignity of his position, and in connection with the difficulties which we have been trying to settle there is no glory. It is like the reward given the dead soldier, i.e. spelling his name wrong in the dispatches. I enclose you clipping from the Bee which the World Herald quotes as from the official bulletin of your headquarters. I would like to be considered as in command of the officers mentioned, not as one of the commanders. As it now stands I am one of the many commanders of the cordon not its commander. I feel that this is not in accordance with the facts and that you will not permit this thing to go unnoticed.[6]

General Miles again reassured Brooke responding with, “I am aware that the press have been somewhat severe in their criticisms and unfair to you. As far as possible I shall endeavor to see that you receive full credit.” Indeed, the day previous to General Brooke’s message bemoaning his lack of credit, General Miles, in an update to the Adjutant General of the Army stated, “General Brooke has commanded his forces with commendable skill and excellent judgment.”[7]

This view certainly was not shared by the press and other civilians at Pine Ridge. Writing to General Leonard W. Colby in the middle of January, Miss Emma C. Sickel wrote of Brooke, “General Brooke is unanimously, and justly, characterized as obstinate, short-sighted and easily deceived…. He was one who knew about facts after they had happened, and seemed to be constructed so that he was mentally incapable of anticipating or preventing any event.”[8]

General Brooke certainly did not relish his role during the campaign. When the Adjutant General of the Army forwarded to General Brooke for endorsement several of Colonel Forsyth’s recommendations for 7th Cavalry officers, Brooke shirked any such responsibility by responding, “At the time this event took place these troops were under my command but all on the Pine Ridge reservation were within the limits of the Department of Dakota. Because of this I reported to General Ruger and considered myself under his control as Department Commander.”[9]

Apparently General Brooke held that winter’s campaign–in which he was perhaps the principal commanding general–in such low regard that he made only an oblique reference to it in his annual report to the Secretary of War for 1891: “In November [1890] the disaffection among the Sioux Indians became so great that it was deemed advisable by the President to use troops in restoring order. This matter was made the subject of a special report at the close of the operations. Since the withdrawal of troops from the Rosebud and Pine Ridge Agencies there has been no evidence of any further disaffection amongst the Indians.” Indeed, General Miles devoted twenty-three of his twenty-four-page report to the Sioux disturbances and subsequent campaign. General Wesley Merritt, who played no role during the campaign but had since taken command of the Department of Dakota, deferred a detailed account of the campaign to his predecessor, General Ruger, but still devoted three of the eight pages of his report to providing extracts from department records detailing events during the campaign. General Ruger, who was by the fall of 1891 commanding the Department of the Pacific, devoted more than seventy pages to detailing the campaign. Despite the lengthy report he refrained from stating anything involving the actions of Brooke and his units during that winter, writing, “In what follows I do not include the operations of the forces assembled at the Rosebud and Pine Ridge agencies… for the reason that Brig. Gen. John R. Brooke, who was in immediate command at Pine Ridge, has, as I am informed, included the services of these forces in his annual report.” General Ruger was misinformed, for General Brooke made no mention of his forces’ services during the campaign.[10]

General Brooke’s failure to render a report on the campaign left a void in the Secretary of War’s annual report regarding the most significant military element of the Pine Ridge Campaign of November 1890 to January 1891. It is an unfortunate gap in the historical record. However, a copy of the “special report” that General Brooke eluded to does exist. It is found in the final pages of the two-volume set of records Brooke presented to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in 1919. Following is Brigadier General John Rutter Brooke’s missing campaign report, excluding the appendixes that he references.

Headquarters Department of the Platte,

Omaha, Nebraska, March 21, 1891.Assistant Adjutant General,

Division of the Missouri, Chicago, Ills.Sir: I have the honor to make the following report of operations during the recent disturbance among the Indians of Pine Ridge and Rosebud Agencies, S.D.

In the first place, I wish to say, that for two years past there has been a growing dissatisfaction and uneasiness among the Indians at these Agencies. This grew more pronounced during the past spring and summer until during the autumn, it became so pronounced that I expected serious consequences in the near future. As I now know, the Indian Agents at these points reported to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs this condition of discontent among the Indians of their respective Agencies.

The Messiah craze seemed to be a means of expressing the feelings of the discontented element.

In November last the feeling of discontent reached such a pass as to lead the Indians to disregard the regulations of the Indian Bureau and they were finally in a condition of open revolt.

I called upon Captain Earnest, of the 8th Infantry, who was Inspector of Indian supplies at the Rosebud Agency, for report of the condition of the Indians of that Agency, copy of his report is hereto appended marked “A.”

I also received two telegrams dated November 16, 1890, from the Agent at Pine Ridge Agency, in which he represented the condition of affairs as very alarming. I transmitted these to the Division Commander who directed me, on the 17th of November, to send two (2) companies of Infantry and one troop of Cavalry, under an efficient field officer, to each Agency to protect the lives and property thereat, and also authorized me to employ such other troops of my Department as might be necessary to restrain, or, in case of an outbreak, to capture or destroy any hostiles at or from these Agencies, and authorizing me to visit them and use my best judgment in avoiding a serious outbreak. In reply to this, I suggested that I be permitted to send more troops at once to each of these Agencies, viz: three (3) Troops of Cavalry and four (4) Companies of Infantry to Pine Ridge, and two (2) Troops of Cavalry and three (3) Companies of Infantry to Rosebud, and also suggested the movement of Infantry to such points along the Freemont, Elkhorn and Missouri Valley Railway, as would give protection to settlers in case of an outbreak. I immediately gave orders for all the troops in the Department, except those at Forts DuChesne and Washakie, and Camp Pilot Butte, to be prepared for immediate field service, leaving one company of Infantry at each post except at Fort Omaha, from which post all the companies were eventually taken.

Being authorized to exercise my judgment, I immediately ordered one (1) Troop of the 9th Cavalry and Major Guy V. Henry, 9th Cavalry, from Fort McKinney to Rushville, and four (4) companies of the 2nd Infantry, under Major Edmund Butler, 2nd Infantry, to proceed by rail from Fort Omaha to Pine Ridge, via Rushville, and one (1) company of the 8th Infantry, and three (3) troops of the 9th Cavalry, from Fort Robinson, via Rushville, to Pine Ridge; also two (2) troops of the 9th Cavalry and three (3) companies of the 8th Infantry, under Lieutenant Colonel Smith being given specific instructions as to his action.

I proceeded in person, via Rushville, to Pine Ridge, arriving there with Major Butler’s command in the early morning of November 20th. The troops for Rosebud arrived there before daylight on November 20th.

After informing myself as to the condition of affairs at Pine Ridge, and in execution of the orders to separate the well-disposed from the disaffected, I requested the Agent to send for those Indians who were well-disposed and who had not defied the authority of the Interior Department, to come to the Agency. This, within a few days, brought nearly all the Ogallala Indians to the Agency. While this was going on reports reached me that 500 lodges of the Indians from the Rosebud Agency were on their way to Pine Ridge. Reports to this effect were also received from the Commanding Officer at Rosebud Agency. Several of the Brles [sic] from the Rosebud Agency subsequently told me that the immediate cause of their hurried move from their homes was the news brought to the reservation by a man named Shaw, living at Valentine, Neb., that the soldiers were coming, and that the Indians would have all their arms and ponies taken from them, together with much more of the same tenor. That the movement was like a prairie fire, the people dropped everything when they heard the news, and gathering such of their property as they could carry, started for the White River and then turned towards Pine Ridge.

The fact, that afterwards appeared, that of certain communities only part of the Indians fled in this way, and that only about 1500 in all left their homes seems to discredit part of this story. The fact that Shaw carried wild stories to the Indians has not been denied up to this time.

Finding that Pine Ridge would be the point at which the trouble would be settled I remained there.

Little Wound’s band of Pine Ridge Indians and the band of White Face became mixed up with these Rosebud Indians and traveled with them as far as the Wounded Knee on their way to the Agency. Little Wound’s people succeeded in extricating themselves at this point and joined that portion of this band that were encamped near the Agency.

From what I could learn of the state of affairs I became convinced that the Indians were alarmed by the action of the Indian Bureau in cutting down their rations, in taking a census which largely decreased the number on which the issues were made and by the non-fulfillment of the promises made by the Sioux Commissioners, and by the fact that the Government seemed to have forgotten its promises or had determined to break them. The failure of their crops had also a very depressing effect on them. They also thought the Army was sent to their reservation as an act of war. I therefore set to work to correct these impressions. I told the Indians I came as a friend, not as an enemy; that I wanted to know the cause of the trouble, &c. &c.

Being authorized by the Secretary of War, I prepared to issue subsistence to suplement [sic] the inadequate issues of the Agency.—see copy of telegram enclosed marked “B”—but the Interior Department prepared to increase the ration to that fixed by the treaty of 1877 and made an issue of rations except beef. I directed an issue of beef to complete the issue made by the Agent in this instance and did not find it necessary to issue again to the Ogallalas, but continued to issue to the Brules who were unable to draw rations at Pine Ridge.

The policy pursued was that of conciliation, and soon its good effects became visible in many ways. The Indians began to feel confidence in the Government and remained quietly in their camps, the influence of the changed feelings reached those in the “Bad Lands” and aided those sent there to bring in the few who seemed to need more than influence alone, and, had not the approach of Big Foot’s band disturbed, for a time, the peaceful situation, I am satisfied there would have been no shot fired and not one drop of blood spilled at Pine Ridge. The fact that no citizen of Nebraska or South Dakota was killed during the troubles is sufficient proof that this opinion is well founded.

The Brules, whose principal leader was Two Strike, together with White Face’s band and some families of the Pine Ridge Agencies, were alarmed by the reports they received from various sources, and turned down Wounded Knee towards White River, and thence to the “Bad Lands.” Finding that these Indians were alarmed by the stories told them by Indians or others and that it was necessary to communicate with them through some source they would regard as reliable, I had a conversation with Father John Jutz, who has charge of the “Mission School” near Pine Ridge Agency. Father Jutz offered to carry any message to the Indians that I might send, I sent by him a message to the effect that I wanted their principal men to come in and talk with me; that we were not there as enemies but as friends. The Reverend Father proceeded at once to their camp, which he found 10 or 15 miles north of White River on the edge of the so-called “Bad Lands.” He gave my message to them, and Two Strike and about thirty of the principal men came back with him, and, on the 6th of December, had a talk with me at my Headquarters.

They represented their grievances and stated that they desired to change their residence from Rosebud to Pine Ridge Agency; that in council with the Ogallalas during the past summer, the latter had consented to their coming to the Pine Ridge Agency; that they had made known to the Department their desires and consent of the Ogallalas, but that they had received no reply. And they asked me what I wanted them to do. I told them that I wanted them to come in with all their people and to do what they were told to do. They replied that they had nothing to eat. I told them that I would give them food and that I would also employ many of them to work. They then said they would return to their people and that they would all return as quickly as they could. I impressed upon them the importance that all should come. To this they assented and left me with the assurance that all their people would be at Pine Ridge as soon as it was possible to get there; and they immediately started for their camp. Meantime Major Henry and one (1) Troop of the 9th Cavalry, Headquarters and eight (8) Troops of the 7th Cavalry and Capron’s Battery, and Headquarters and four (4) Companies of the 2nd Infantry, had reported to me, making the force at Pine Ridge, nine (9) companies of infantry, twelve (12) troops of Cavalry, and Capron’s Battery, which I considered to be sufficient for all purposes at this point. I had ordered four (4) companies of the 21st Infantry, from Fort Sidney, to join me at Pine Ridge, but afterward directed them to Rosebud Agency. The march of this battalion from Valentine to Rosebud Agency—35 miles in 13 hours—was one of the best on record and deserves special commendation. Seven (7) companies of Infantry from Fort D. A. Russell, were ordered to Fort Robinson to encamp, and arrived there on December, 18th. The 1st Infantry from the Department of California was ordered, on December 8th, to Fort Niobrara to there await further orders.

I had received several reports from Col. Carr, commanding 6th Cavalry, as to his whereabouts, but had no information that he was to report to me. I was subsequently informed from my Headquarters at Omaha, that transportation had been furnished the 6th Cavalry to Fort Meade. I then suggested to General Ruger, Commanding the Department of Dakota, that this regiment be stopped at Rapid City, for service along the Cheyenne River—The situation at this time, December 7th, was this, all the Ogallalas, except those with the Brules in edge of “Bad Lands” and Young-Man-Afraid-of-his-Horses’ band, were in camp about the Agency. All the Indians of the Rosebud Agency not near the “Bad Lands” were at their homes on their reservation. There were seven (7) companies of Infantry and two (2) troops of Cavalry at the Rosebud Agency, nine (9) companies of Infantry, twelve (12) troops of Cavalry and Capron’s Battery at Pine Ridge Agency, the 1st Infantry en-route to Fort Niobrara and the Battalion 17th Infantry en-route to Fort Robinson, two (2) troops 8th Cavalry and Battalion of Cavalry from Fort Leavenworth at Oelrichs.

The temper of the Indians at Pine Ridge was apparently all that could be desired.

Every effort was being made to properly equip the troops for a winter in the field, preparing Hotchkiss guns and otherwise making all possible preparations for a successful winter campaign, should it become necessary.

At the same time every effort was being made to convince the Indians that the Government desired no war with them, but that it insisted upon them obeying the regulations prescribed for their government, I believe that the large force of troops, present, and the plainly visible preparations being made for continuous and active field operations, aided largely in impressing the Indians with the futility of any hostile acts on their part. This with the increase of food tended to allay the disaffection existing amongst them, and the promises of the Government to fulfill its treaty obligations with them took away all cause of disaffection on their part, which disaffection had its main origin in the reduction of supplies secured to them by treaty, together with the deferred execution of the promises made them by the Sioux Commission.

All this time a number of Ogallalas and Cheyennes were being enlisted as scouts.

On the return of Two Strike and those with him to their village they were accompanied by two interpreters, Baptiste Garnier and Louis Shangroux, and a small detachment of Indian scouts. Reports were received from the interpreters by couriers, daily, which indicated that Two Strike and his comrades were carrying out their promise to come in, and that the whole band had agreed to stand by the promises which the delegation had made me. The Indians commenced to move back to White River where a few young Indians, said to be led by an Indian named White Tail, developed strong opposition to this movement. This led to an altercation in which clubs and like weapons were freely used, and which resulted finally in about six hundred (600) or Seven hundred (700) of both sexes turning back, voluntarily, and being driven back, and finally settling on the high table land called “Bad Lands.” The rest of the Indians moved towards the Agency, and about the 15th of December arrived there about eight hundred and fifty (850) strong, camped at the spot designated and rations were then issued to them. Some bread coffee and sugar had also been sent to them while on their way in.

Considering that every means had now been exhausted to bring in the Indians and feeling satisfied that a rigid compliance with the President’s order to avoid war and bloodshed had been made, I felt that the time had arrived when the Indians now camped in the “Bad Lands” should be surrounded and brought in by the troops. I believed that this should be done at the earliest possible moment, and thus prevent these Indians leaving the reservation and endangering the border settlements. I therefore commenced preparations to do this, at the same time keeping up a constant communication through well-disposed Indians with this camp and making every effort to withdraw the families, one by one. In this way probably one hundred (100) Indians were withdrawn from the camp.

![(Click to enlarge) Section of “Map of the Pine Ridge & Rosebud Indian Reservations and Adjacent Territory,” prepared by the Department of the Platte Engineer Office from 1890 authorities.[2]](https://armyatwoundedknee.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/brookes-map-from-pine-ridge-1890.jpg?w=625&h=541)

(Click to enlarge) Section of “Map of the Pine Ridge & Rosebud Indian Reservations and Adjacent Territory,” prepared by the Department of the Platte Engineer Office from 1890 authorities. William F. Kelley, Pine Ridge 1890: An Eye Witness Account of the Events Surrounding the Fighting at Wounded Knee.

All arrangements being completed and stations of various commands being appointed, orders were given for all troops to be in position indicated, on December 17th and to move on those encamped in the “Bad Lands.” I reported, then, my purpose to General Ruger, Commanding Department of Dakota.

When news came of the killing of Sitting Bull, the Division Commander ordered a suspension of the movement, upon which I immediately resumed my efforts to disintegrate the camp, by means of large delegation of Ogallalas and Brule Indians. About forty (40) of both tribes were selected in their councils and an Ogallala, Plenty Buffalo Chips, placed in charge. These Indians went to the camp and were met with insults and defiance. They returned and reported the failure of their mission. I then asked them what they thought had better be done with these people. The reply was “we will consult our people and let you know what we think.” A council was called by the Indians at the Agency, who then numbered nearly seven thousand (7000), and it was decided to send five hundred (500) men to bring the Indians in from the “Bad Lands,” but during the night some influence became active among them to defeat this, and the next day but few Indians were found ready to go. I sent a message to Red Cloud, American Horse, Little Wound, Big Road, and others, which resulted in about one hundred and forty (140) Indians under the leadership of Little Wound, Fast Thunder, Big Road and other lesser chiefs starting for the “Bad Lands.” They were unaccompanied, by their own desire, by any of my interpreters or scouts. I was to be kept informed daily of their movements however, and finally a message in writing (Sioux) was received from them, stating that they were bringing in the whole band.

During the negotiations, on December 23rd, I was informed by the Division Commander that Big Foot’s band had eluded Colonel Sumner and was moving south. I immediately started Major Henry with his battalion of the 9th Cavalry, and Lieutenant Hayden’s platoon of Hotchkiss guns to take position north of White River and east of the “Bad Lands,” and prevent Big Foot from joining the Indians there. Major Henry’s march of 45 miles in 7 hours, most of which was at night, deserves especial mention as one of the best evidences of what can be done by an able and energetic commander with a well equipped and well disciplined body of troops. Colonel Carr was to the north and east of Major Henry.

These movements effectually prevented the junction of Big Foot with the Indians on the way to the Agency.

Early on December 26th, I learned that Big Foot’s band was south of White River and moving towards the Agency. I sent a battalion of the 7th Cavalry and a platoon of Hotchkiss guns under Major S. M. Whitside, 7th Cavalry, to Wounded Knee at the crossing of the Rosebud road, to scout south and north on Wounded Knee Creek, connecting with Major Henry, and to capture and hold any Indians found. The Ogallala scouts sent with this command, being new to service and undisciplined, passed beyond the reach of the command and were of little use to it. Ascertaining this on the 27th, I sent Baptiste Grainer [sic] with a few selected Indian scouts to Major Whitside, to supply their place. During the time I received reports from the Indians coming from the “Bad Lands,” who were making their way slowly towards the Agency. On the 28th, I received a report from Major Whitside, announcing the capture of Big Foot and his band east of Wounded Knee Creek. In this report Major Whitside stated that he did not consider it prudent to attempt to disarm them with the force he then had. I then sent Col. Forsythe with the remaining battalion of his regiment and a platoon of Hotchkiss guns to Wounded Knee, directing him, verbally, to assure the Indians of kind treatment and to disarm them, and if they should fight to destroy them. I communicated the capture of Big Foot’s band to the Division Commander, and suggested that they be sent to Gordon, Nebraska, and thence by rail out of the country, indicating Omaha, as a point to which to send them, and this being approved, I immediately made preparations for this purpose and suggested also, that the troops on Cheyenne River be moved down to White River.

On the morning of the 29th, rumors reached me of a fight in the direction of Wounded Knee, which was confirmed about 11 a.m., by a report from Colonel Forsyth, saying that in attempting to disarm Big Foot’s band, they fought, which resulted in the killing of about ninety (90) bucks and wounding of about twenty (20) more. A large number of squaws and children were also killed and wounded. Our loss being one officer and twenty-five (25) enlisted men killed, one being an Indian scout, and two (2) officers and thirty-two (32) enlisted men wounded. Interpreter Wells was also wounded. The dead and wounded officers and soldiers were brought to the Agency; also all wounded Indians that were found. As soon as the news of the fight reached the Brule camp of Two Strike, a number of young Indians from that camp, estimated to number about one hundred and fifty (150), started out in the direction of Wounded Knee. These attacked Captain Jackson’s Troops, of the 7th Cavalry, and in the fight which ensued, he was compelled to drop twenty-three (23) prisoners he had gathered up. On returning these Indians attacked the Agency. Their fire was replied to by the Indian Police. The troops were placed in positions previously indicated in case of necessity but did not fire a shot. Two (2) soldiers were wounded, however, by the fire from the attacking party.

The bands of Big Road and Little Wound moved during the morning of this day and joined Red Cloud’s camp. The attack upon the Agency was principally from the ridge to the north, but a number of shots were fired from the camps before named. The return fire drove the people out of their camps, and towards evening they were gathered together by the young men, evidently those engaged in the attack, and were driven up the ridge to the west and thence north and into the valley of the White Clay below the “Mission,” there joining the Indians who were on their way from the “Bad Land.” The Indians who were bringing in those from the “Bad Lands,” and those of the camps mentioned, were now practically prisoners under control of the young Brules, who were, doubtless, joined by some young Ogallalas.

About 10 o’clock P.M., Colonel Forsyth arrived with his regiment bringing the dead and wounded officers and soldiers, and the wounded Indians and some prisoners. On this day the Commanding Officer at Rosebud Agency was directed to send his two (2) troops of Cavalry and one company of Infantry to Pine Ridge. This command was subsequently stopped at the crossing of the Rosebud road with the Wounded Knee, and assisted in the burial of the Indians killed in the fight at that point.

I communicated with Major Henry, at the mouth of Wounded Knee, the situation about the Agency and warned him of probable attack in large force, and directed him to communicate with Colonel Carr or any troops near him, and united with them. Major Henry seems not to have received this communication, and, acting upon a previous one, marched with all speed towards the Agency, reaching there about daylight on the morning of the 30th. His train being some distance in the rear, escorted by Loud’s Troop D, 9th Cavalry, was attacked about three (3) miles from the Agency by the Indians. A soldier of the advance guard and his horse were killed by the Indians dressed in the uniform of soldiers. Captain Loud parked the train and prepared to defend it and sent a courier to Major Henry announcing the state of affairs.

Major Henry, having barely arrived in the camp, started back with all speed, relieved the train and brought it in. I sent Colonel Forsyth with his regiment to join Major Henry and avoid any possibility of disaster.

Early on the morning of the 30th, a column of smoke being seen down the White Clay in the direction of the “Mission,” I sent Colonel Forsyth, with his regiment, to save the “Mission,” should the Indians be trying to destroy it. They found, however, that the Indians were burning some of the school houses above and below the “Mission.”

The scouts reported that the sound of guns was heard down White Clay towards White River, and Colonel Forsyth moved in that direction, sending back for the battalion of the 9th Cavalry, encountered the Indians, and after skirmishing with them for some time, returned to the Agency. In this affair one soldier was killed and one (1) officer and five (5) soldiers wounded.

The gallantry of officers and soldiers in the action at Wounded Knee is worthy of the highest praise. Women and children were killed and wounded, but this could not be avoided under the circumstances.

During the excitement of the 29th and 30th, the Indians classed as well-disposed or friendly, numbering about three-fifths (3/5) of the Ogallalas and all the Cheyennes, remained in their camp at the Agency, and announced their willingness to fight with us against the other Indians, and asked for arms and ammunition. Subsequent events satisfied me that these Indians were sincere, and I believe would have been trustworthy had arms and ammunition been placed in their hands. During the 29th and 30th frequent communications was had with the Division Commander in which I suggested the advisability of pushing all troops along the Cheyenne River to a new line on White River. The troops at Oelrichs, being under my command, were ordered to the Agency, moving down White Clay Creek, I directed Lieutenant Colonel Sanford, 9th Cavalry, commanding troops from Oelrichs, to halt at the mouth of White Clay, and to prevent the Indians escaping to the north, and to cover the country to the south and west.

I was informed by the Division Commander that the commands of Wells, Offley and Carr, would be on White River on the evening of the 30th, or morning of the 31st.

The 31st of December was spent in preparing the command at the Agency for any service they might be called to perform. The Division Commander arrived at the Agency at about 12 o’clock noon on the 31st of December, and after consultation, verbally directed me to take such troops as I saw proper from the force then at the Agency and to place a force between the point where the Chadron and Pine Ridge road crosses Little Beaver Creek, and the right of Lieutenant Colonel Sanford’s line on the White River; and to proceed along the line of troops on White River and up on Wounded Knee and thence back to the Agency. The advance of the 1st Infantry arrived at the Agency in the afternoon and I was advised that the rest of it was on its way. I therefore ordered the 2nd Infantry, Major Henry’s Battalion of the 9th Cavalry, and Hayden’s platoon of Hotchkiss guns to be prepared to march at an early hour, taking with them fifteen days rations and forage. Later in the day I received written instructions from the Division Commander, giving in considerable detail, general directions for dispositions & action of the troops forming the circle around the Indians between the Agency and the White River. On the early morning of this day a blizzard set in which continued until late at night.

On the 1st of January I marched with the 2nd Infantry and battalion of the 9th Cavalry for White River. After proceeding a few miles I found a shorter road to White River than that by way of Beaver Creek. I took this road and reached White River at a point about fourteen (14) miles from the Agency. I left Colonel Wheaton’s command at this point. On the following morning, about January 2nd, I went down White River, finding Lieutenant Colonel Sanford and his command and Casey’s and Strother’s Cheyenne scouts. Going on I reached Offley’s camp at the “flour-road” crossing of White River. On this day I gave specific instructions to all commanders on White River and Wounded Knee Creek, regarding patrols and scouts, with a view to preventing any Indians from escaping through the lines.

Colonel Carr forwarded, under date January 2nd, the report of Captain Kerr, 6th Cavalry, of an engagement between his Troops and Indians, on the north bank of White River, near mouth of Little Grass Creek. After a skirmish the Indians were defeated with loss. Copy of Captain Kerr’s report enclosed marked “C”.

I changed the location of Offley’s camp and then went on to Colonel Carr’s camp on Wounded Knee, near its junction with White River. I remained at this camp the following day, acquainting myself with the country between this point and the adjacent camps. I also withdrew Strother’s Cheyenne scouts from Sanford and ordered them to report to Colonel Carr. At this point I received directions from the Division Commander to remain on this line and to gradually close it and force the Indians towards the Agency.

On January 4th I directed Colonel Wheaton to move down White River to a point about five (5) miles from Sanford’s camp. On the 5th of January I returned to Sanford’s camp and established my Headquarters there. On the 6th I directed four (4) companies of the 2nd Infantry to report to Colonel Sanford, and the company of the 17th Infantry then with him, to join the rest of the regiment under Lieutenant Colonel Offley, four (4) miles below. On the morning of this day one of the Cheyenne scouts came into camp and informed me that Lieutenant Casey had been killed by a young Brule, while he was reconnoitering near the hostile camp. Later in the day Lieutenant Getty succeeded in securing the body, which was partially stripped but not mutilated.

Scouts and patrols were active. Those from Carr moved to the south and west, Offley’s south and east, Sanford’s to the east and west, and Wheaton’s to the south and east, the Cheyenne and Ogallala scouts observing the camp of the Indians on White Clay Creek. A bridge was constructed across White River by Colonel Wheaton and the ford at Sanford’s camp improved, and two (2) fords constructed at Offley’s camp, thus enabling a quick passage of the River by the troops of these commands.

While at this point many Indians communicated with our scouts and some came in to talk to me. They all claimed that they were being practically held as prisoners by the young Brules.

From information received from the Division Commander, I made every preparation to close the line towards the Agency and directed all commands to be ready to move at short notice.

On the 9th of January, I directed Colonel Carr to move two (2) battalions of his regiment up the Wounded Knee to positions between his camp and that of Whitney, who was on the battle ground of Wounded Knee, and to scout continually towards the White Clay. I also moved Captain Wells’ battalion of the 8th Cavalry down White River to mouth of Little Grass Creek.

On January 10th I directed Colonel Wheaton to move back to near his original camp on White River and to the “Two Well”, on the road on which he marched out, which proved to be impracticable, however, and Colonel Wheaton camped on White River.

The Indians on this day, 10th, moved down from the hills on No Water Creek towards White Clay, and all preparations were made to follow them closely on their way to the Agency, Colonel Carr being ordered to close up on his left and cover the country towards White Clay and be prepared to move in towards the Agency on receipt of orders to do so. On the 10th Captain Wells moved in close to the Indians, scouting the country between Little Grass Creek and White Clay. On the 11th Lieutenant Colonel Sanford and Lieutenant Colonel Offley moved up White Clay, Captain Wells moving parallel to and a little distance east of White Clay and joined the main command at its camp. In the evening I ordered Colonel Wheaton to send Major Henry’s battalion to join me the next morning and also communicated the situation to Colonel Carr, and ordered him to be ready to move towards the Agency upon the receipt of orders. On the evening of the 12th, the Indians continued the march towards the Agency and were followed closely by the troops, Captain Wells’ battalion moving to the eastward of White Clay, scouting as far east as possible, seeing the scouting parties of Colonel Carr’s command. Major Henry’s battalion joined on the march. Colonel Wheaton camped at “Two Wells.” Carr moved up Wounded Knee, his right being on White Horse Creek, about twelve miles from the “Mission,” at which latter point the main body camped on the evening of the 12th. On the 13th I brought Colonel Wheaton’s command over from the “Two Wells,” to join the main force. During this and the following day the troops remained in camp at this point, patroling [sic] to the east and west and keeping a close observation of the Indian Camp, which was between this point and the Agency.

Captain Whitney’s command and Major Perry, with one battalion 6th Cavalry, were ordered, on the 14th, to camp on Wolf Creek near the Agency, Colonel Carr accompanied this battalion of his regiment.

On the morning of the 15th, the Indians, who were driven from the Agency by the young Brules, moved into camp south of the Agency.

On this same morning, in pursuance of the orders of the Division Commander, Colonel Wheaton, with his regiment and five troops of Cavalry, were ordered to march to Craven Creek, south-west of the Agency, and the 6th Cavalry was ordered to move to Wolf Creek, near the beef corral.

The main command moved forward and occupied the ground vacated in the morning by the Indians.

At this point troops and companies of the various regiments, which had been separated during the recent movements, were united as much as possible.

The troops were kept moving in patrols, connecting the various camps, for a few days.

On January 18th, in General Orders No. 3, the Division Commander announced the cessation of hostilities.

On January 21st all troops engaged in the campaign, except the 1st Infantry and the Indian scouts, were assembled in camp on White Clay Creek near mouth of Craven Creek.

From the 1st of January, and in fact from the 28th of December to the 20th of January, a season of intense activity prevailed and all officers and men acquitted themselves most creditably. The Cheyenne scouts under Lieutenants Casey and Getty, were conspicuous for the good service they performed. The Cheyenne scouts under Lieutenant Strother’s command did exceedingly well considering the fact that they were but a short time in service. Taylor’s company of Ogallala scouts were at the fight at Wounded Knee and did excellent service during the whole period of the disturbance. A detachment of these scouts under Lieutenant Preston deserves the same mention as the Cheyennes under Lieutenant Strother.

On the 20th of January was commenced the work of reducing expenses and preparations to withdraw the troops and distribute them to their various stations.

The necessary orders being issued, and all the troops having left the Agency, except the Cheyenne scouts and Taylor’s Ogallala scouts, 1st Infantry, battalion of the 9th Cavalry under Major Henry, and six (6) troops of the 6th Cavalry, which latter were to remain for a few days only, I left the Agency on the 25th of January and reached my Headquarters on the 26th.

It seems to me to be proper to state here that I had several telegrams from the Governor of Wyoming, saying that the people of the northeastern portion of the state were very apprehensive of attacks from Indians, and saying that there were a large number of Indians in the “Powder River Country” I know that Young-Man-Afraid-of-His-Horses and his band were moving through that section towards the Crow Agency on a visit to those Indians and that they were hunting as they went along. This band of Indians was absent by permission of the Agent at Pine Ridge, and I was satisfied there was nothing hostile in their intentions, all of which was communicated to the Governor and the people became quiet. The reports here alluded to were found to be groundless in fact, but in the excited condition of the public mind such reports did not surprise me.

There were many instances of personal inquiry by people on the border of the Indian Reservation regarding the situation, to all of which I replied that ample protection would be afforded in case necessity arose. I had troops at Forts D. A. Russell and Douglas ready to send to any threatened points at short notice, and these troops were brought to the field finally, those from Fort D. A. Russell on December 17, and those from Fort Douglas on December 31st.

I sent Major Benham of my staff to investigate certain reports from Merino, Wyoming, to the effect that there was a large number of Indians in that section of the country and believed to be planning mischief; that the Indians were near the camp of the graders on the Burlington and Missouri Railway, who were unprotected. Major Benham reported (copies of reports enclosed marked “D” and “E”), after investigation, that the general impression at the points visited by him was to the effect that the few Indians in the country were harmless and that the presence of troops was unnecessary.

I would invite attention to telegram of November 25th, 1890, from Division Headquarters (copy enclosed marked “F”), with reference to cause of disaffection and remedies to be applied, and to my telegram of November 26th and letter of November 30th (copies enclosed marked “G” and “H” respectively) in reply thereto.

I desire in closing my report to say that I do not think anything was omitted by the various departments to thoroughly equip and supply the troops under my command, and I do not think troops ever were so thoroughly equipped for winter service before. Nor have the sick and wounded in Indian campaigns ever had such thorough provision made for their care and comfort.

The Chiefs of Departments in Washington acted promptly in all cases and the result is seen in the reports of the Chiefs of the Staff Corps under my command.

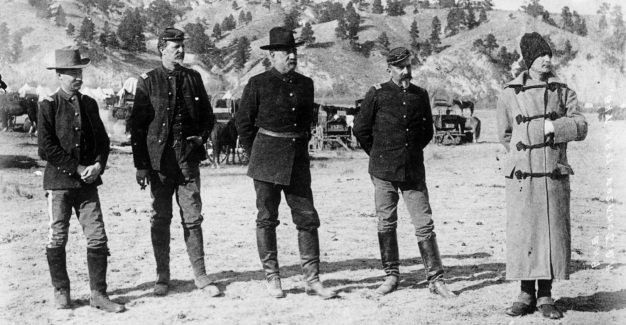

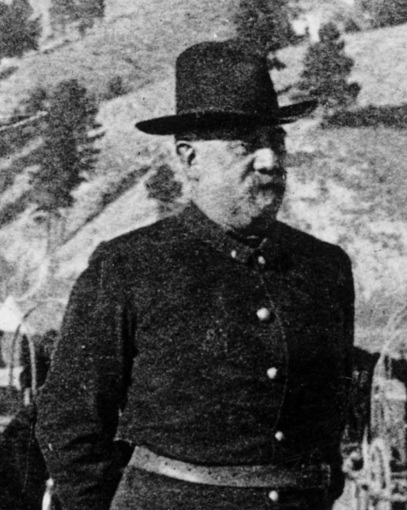

Brigadier General John R. Brooke and staff at Pine Ridge, published January 1891 by A. G. Johnson, York, Nebraska. Left to right 1st Lt. C. M. Truitt, 21st Infantry, Aide-de-camp; Maj. D. W. Benham, 7th Infantry, Inspector of rifle practice; Gen. Brooke, Commander, Department of the Platte; Maj. J. M. Bacon, 7th Cavalry, Inspector General; 1st Lt. F. W. Roe, 3rd Infantry, Aide-de-camp. Photograph is from the Denver Public Library Western History Collection, Call number x-31491.

The officers of my Staff in the field with me, 1st Lieutenants F. W. Roe and C. M. Truitt, Aides-de-Camp, Major J. M. Bacon, Acting Inspector General, Major D. W. Benham, Inspector of Small Arms Practice, and Lieutenant Colonel D. Bache, Medical Director of the Department and Captain C. F. Humphrey, A. Q. M., Acting Chief Quartermaster in the field, 1st Lieut. J. S. Mallory, 2d Infantry, Acting Chief C. S., in the field, and Capt. Geo. Ruhlen, A. Q. M., on duty at Rushville, Neb., all of whom deserve especial mention for the able manner in which they performed their various duties.

The labors of Major M. V. Sheridan, Asst. Adjutant General, Lieut. Colonel W. B. Hughes, Chief Quartermaster, Major W. H. Bell, Chief Commissary of Subsistence and Captain J. C. Ayers, Chief Ordnance Officer of the Department were great and conducted largely to the success of the campaign.

Very respectfully, Your obedient servant,

John R. Brooke, Brigadier General, Commanding.[11]

Endnotes:

[1] U.S. Army Register for 1891 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891), 6 and 274.

[2] John R. Brooke, Sioux Campaign 1890-91, vols. 1 and 2 (Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1919), 104. These documents were typed and certified as true copies by 1st Lieut. James T. Dean who served as aide-de-camp to General Brooke from February 1893 to May 1895. These original certified copies appear to have been bound into two volumes and an index likely by Lieut. Dean during that same time frame. A label in the front of each volume indicates that they were presented by General Brooke to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania on 21 May 1919.

[3] Ibid., 236-238.

[4] Ibid., 692-739.

[5] Omaha Bee, 2 Jan 1891.

[6] Brooke, Sioux Campaign 1890-91, 901.

[7] Ibid., 899 and 902.

[8] Leonard W. Colby, “The Sioux Indian War 1890-’91” in Transactions and Reports of the Nebraska State Historical Society, vol. 3 (Freemont, NE: Hammond Bros., Printers, 1892), 180-185.

[9] Adjutant General’s Office, Medal of Honor, Principal Record Division, file 3466, Record Group: 94, Stack area: 8W3, Row: 7, Compartment 30, Shelf: 2. Research conducted by Vonnie S. Zullo of The Horse Soldier Research Service.

[10] United States War Department, Annual Report of the Secretary of War, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1892), 162, 181, and 252.

[11] Ibid., 1030-1047.

Citation for this article: Samuel L. Russell, “Brigadier General John Rutter Brooke and His Forgotten Campaign Report,” Army at Wounded Knee (Carlisle, PA: Russell Russell Martial, 2015-2016, http://wp.me/p3NoJy-UT) posted 6 Feb 2016, accessed date __________.

As a historian of the Lakota, I’m thrilled to read so much more detail about the native political background as the tragedy of 1890 unfolded. Thanks for this great website, Sam!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Kingsley… Thank you for taking the time to comment. Your expertise is and commentary are always welcome.

Sam

LikeLike

Thank you for your research and making available documents key to the unfolding of events before and after Wounded Knee. The story of Chief Spotted Elk (aka “Big Foot”) and his people has sadly been forgotten and debased by the histrionic narrative and historical degradation of those events by radical scholars in the company of criminals like Leonard Peltier and Dennis Banks. Chief Spotted Elk was a man of peace, who reluctantly but ably endeavored to help his people transition to the “white mans” ways. My grandmother was a half-blood Miniconjou, the land Spotted Elk and his people left that cold day in December, headed to Pine Ridge, a mere 30 miles west of where I grew up, on a ranch, on the Cheyenne River in western South Dakota. Spotted Elk was invited to spend the “holidays” with Red Cloud at Pine Ridge and was not headed to the badlands as many people have been lead to believe. Spotted Elk wanted nothing to do with the ghost dance and it’s practitioners and did not approve of his people practicing the ceremony in his camp. Indeed, the reason Sitting Bull died, was because he allowed his people to practice the ghost dance ceremony, which had been forbidden. James McLaughlin, stationed at Ft Yates, agent for Standing Rock reservation, sent tribal police to arrest Sitting Bull because Sitting Bull refused to stop practicing the bastardized version of Wavoka’s peaceful “ghost dance”. Like the American Indian Movement of the 20th century, Sitting Bull wanted the white man removed by any means necessary, including murder, if need be. So they practiced a form of the ghost dance that included the blessing of a shirt (white), that when worn by a practitioner, would repel bullets. The day Sitting Bull was shot, most his people scattered, fearful of harsh retribution for the killing of four indian police. Some of these people joined with Spotted Elks group, who were not far from where Sitting Bull was camped on the Grand River in north-central South Dakota. Spotted Elk was camped on the Cheyenne River about 100 miles south. I wanted you to understand the lead up to these events, many documented by Lt Sumner, who Gen Brooke claims “allowed(Big Foot) to escape”. Lt Sumner had a good rapport and trusted Spotted Elk. The day that Spotted Elk left for Pine Ridge, he had promised Lt Sumner he would take his people to their agency located on the Missouri River at Lower Brule (Lower Brule/Crow Creek agency), on order of Gen Ruger. Possibly because of rumors started and spread by gossip among and between tribes (referred to in Gen Brookes report), regarding the movement of troops to crush any uprising, then the arrival of Sitting Bulls people, warning of retribution, a sickly Spotted Elk headed south to meet his fate. Mr Russell, I cannot express the appreciation for your finding and posting of these documents. It bothers me that to this day, most of the sites who refer to wounded knee claim it was a massacre, a slaughter, many claiming all 300 of Spotted Elks tribe were murdered. Even members of my family cling to the narrative that soldiers were supposed to have said “this is for Custer”, just because Custer happened to be 7th Calvary. Makes for great theater, but it shames the dead who deserve to have the truth told. Mr Russell, the only piece of the puzzle that I cannot reconcile is the use of the Hotchkisses. Who ordered them fired? And with combat hand to hand, and so many women and children in close proximity, Why?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mr. Mortenson…

Thank for commenting and for providing such detail.

I understand that Big Foot was called Spotted Elk earlier in life, and I often see modern day references to him by that name, particularly from Lakota Native Americans. All contemporary references address him as Big Foot, and historians like Utley and Greene have explained that at the time of Wounded Knee, he went by the name Big Foot. I assume that the Lakota today prefer to use his younger name because of a perceived negative connotation to the name he was known by at the time of his death.

Regarding the Hotchkiss steel mountain rifles, Maj. Whitside and Lieut. Hawthorne placed the first two in an over watch position on the hill above the Indian camp when they brought the captured band back to the cavalry camp at Wounded Knee. Capt. Capron, commander of Light Battery E, brought out two more Hotchkiss rifles with Col. Forsyth the evening of December 28, and positioned them on the hill as well. During the opening of hostilities, and during the initial melee and hand-to-hand fighting, Capt. Capron ordered the primers removed from the guns to ensure that they were not inadvertently fired on soldiers engaged in the fight. He ordered the guns to fire once the Indians broke through the soldier perimeter and headed toward the ravine. According to testimony, some Indians took up concealed positions on the ground under blankets, in tepees, and in government tents. Capt. Capron fired on the village tepees where they could identify that Indians were firing from within. As the Indians fled to the ravine and took up covered and concealed positions, they began returning effective fire on the soldiers, creating a number of casualties, including several dead. Capt. Capron then ordered his guns to move toward the ravine to pour in more effective fire and eliminate the enemy fire coming from the ravine. Unfortunately, many women and children were killed in the ravine from the Hotchkiss fire.

LikeLike

Thank you for the explanation. You’re correct, it was not uncommon for men to have two or more names in their lives, Crazy Horse comes to mind as an example. Were the Hotchkiss the 42mm revolving cannons? I can’t help but place blame on those in Big Foots group who knowingly placed innocent women and children at risk. Normally, the Sioux (Lakota) were very protective of their women and children, fierce when holding off soldiers long enough for innocents to escape. Many of Crazy Horses contemporaries said he was haunted by the faces of dead women and children he believed were murdered for no reason. Crazy Horse would never have allowed rogue warriors to start a fight with the outcome as obvious as wounded knee. Too much blame is laid on the army, not enough on the governments incompetence and double-dealing.

LikeLike

This is perhaps the best description I have been able to find regarding the Hotchkiss mountain rifle.

LikeLike