The statement of the services immediately performed by Capt. Hurst and Lieut. Hale carries with it so evident a suggestion of every meritorious conduct on their part that special remark thereof would seem superfluous.

–Brigadier General Thomas H. Ruger

Second Lieutenant Harry Clay Hale of the 12th Infantry was twenty-nine years old and seven years out of the United States Military Academy when his duty called him into action during the Sioux campaign. Captain Joseph Henry Hurst was fifty-four and an emigrant from England who served with the 141st Pennsylvania Volunteers during the Civil War receiving brevet promotions for gallantry at Chancellorsville and Spotsylvania. Hurst had been a captain with the 12th Infantry since 1886. If there were only two men in the United States Army that winter of 1890-1891 capable of convincing hundreds of “hostile” Indians to surrender their weapons and submit peacefully to the will of the government, it was Lieutenant Hale and Captain Hurst. Their accomplishment is singularly extraordinary and came on the heels of Sitting Bull’s death where Captain Fechét had ridden to the rescue of the Standing Rock Agency Indian police on 15 December. Over two hundred of Sitting Bull’s followers that day fled their camp at Standing Rock, ostensibly to join Big Foot’s band of Miniconjou, wage war on the country side, and seek vengeance for their fallen chief. In truth, they were terrified, starving, freezing, and understandably distrustful of soldiers, making them potentially dangerous to anyone in uniform. 125 years ago today, Lieutenant Hale rode up by himself to confront this band of fugitive Indians, and see if he could convince them to surrender. Six days later he filed the following report.

On the 18th instant I started in company with Post Guide Nolland for vicinity of Cherry Creek. We arrived at Cheyenne City, near the mouth of Cherry Creek, at 6:50 p.m., same date, and found but one white man left there, the others having fled at about 1 o’clock the day previous for fear of their lives, leaving most of their property behind them. I was informed that they left in a panic and the panic was caused by Narcesse Narcelle, half-breed agency farmer, and lately employed in trying to induce Cherry Creek Indians to give up their arms, etc., who rode into town about noon of the 17th instant, and advised all the whites to leave the place immediately. The cause of his fear was the arrival of some runners from Sitting Bull’s fugitive band, who had said that a party of warriors would arrive at Cherry Creek that night; that they were all desperate men; that they had sworn to kill the first white man or Indian policeman they should see, etc. He appeared frightened himself, and left Cherry Creek the next morning for Bennett. These facts I learned from the one white man whom I found remaining at Cheyenne City; and since that time his statements to me have been essentially corroborated.

On my arrival at Cheyenne City I sent such Indians as I could pick up out on various duties. One and all having refused to go with me to Cherry Creek, I finally induced one–not a policeman–to go alone with instructions to find out all he could concerning the number of Sitting Bull’s band then at that place, etc. Another Indian, a policeman, I sent down the river to bring back Narcisse Narcelle.

The result of my investigations that night are embodied in my report to Capt. J. H. Hurst, Twelfth Infantry, commanding Fort Bennett, S. Dak., appended A. I also reported that night to the commanding officer camp on the Cheyenne by a runner. My report to him was to the effect that the Sitting Bull Indians were well up the Cherry Creek. To this communication I received no answer when the runner returned several days later. My reports (appended B and C) afterwards sent in, carry me up to about noon of the 20th instant. During this period difficulty was experienced at arriving at facts as I had no interpreter but Mr. Henry Angell the white man left in Cheyenne City, who had picked up some of the Indian language during his residence among them. Horses were kept saddled and a watch maintained at night as all reports to the temper of the surrounding Indians were of an alarming nature. About noon of the 20th instant an Indian came in and reported that Cavanaugh’s ranch, distant about 10 miles, had been looted that morning and the onwers [sic] run off. The question arose as to whether this (if true) had been done by the Standing Rock Indians or by disaffected Cherry Creek Indians on their way to join Big Foot. I immediately determined to go up Cherry Creek myself in quest of the camp of Standing Rock Indians, as I had been as yet unable to possibly fix their location. As I was about to start, Hump rode into camp and told me that the Standing Rock Indians were not far distant and approaching in our direction, and that they were armed. Soon I could see them coming down over the hills a mile distant and from the direction of Cavanaugh’s ranch. I believed that they were from that place, and decided to ride out and meet them with the view of preventing them, if possible, from doing damage to Cheyenne City. Just then Hump approached me and by signs asked me if I would go with him and meet them. I assented, and we rode over to where they had come in, and in a few moments I found from their manner that they were friendly. I counted forty-six men, many of whom were armed. There were a few women, two or three wagons, and a small herd of ponies near. I appreciated the importance of the situation, but was absolutely powerless to communicate with the Indians. I immediately formed the opinion that they could be easily persuaded to come into the agency if I could but talk to them. While I was trying by signs to make them understand what I wanted, Henry Angell rode into the circle and took his place at my side. This generous man had not liked the idea of my going amongst these Indians, and from a true spirit of chivalry had ridden over to “see it out.” By this time I had made up my mind what to do, and by Angell’s knowledge of the language I told the Indians that if they would remain where they were for twenty-four hours I would go into the agency and would return to them with the chief and an interpreter and with no soldiers with us in that time. They indicated that they would not move, and having directed Angell to kill a beef and feed them I started for the post, reached there in six and one-half hours, and in company with the post commander, Capt. Hurst, and interpreter, was back the next afternoon. Hump was left in charge during my absence. My fear was that some of Big Foot’s men would come down the river amongst Standing Rock Indians during my absence and ruin my plans.

Early on the morning of the 22d instant we started for Fort Bennett with the Indians, camped that night 2 miles above Dupree’s ranch. On the morning of the 23d instant I was directed by Capt. Hurst to take charge of the Indians and conduct them on to the post. He then went on to the post alone. Meantime eight box and five spring wagons had arrived from the agency at the request of Capt. Hurst, to convey those who could not walk. The column was started at 1 o’clock p.m., camped that night at Cook’s Camp, 23 miles from Fort Bennett. The weather was cold and much suffering was endured by the poorly clad and tired Indians. A beef was purchased, killed, and, together with sugar and coffee, sent from the agency, issued under my direction. Camp was broken at daylight on the 24th, and at 9:30 I drove out in rear of the last wagon full. It was a cold morning and considerable suffering was manifest. The column arrived at Fort Bennett at about 5:30 p.m., same date. On the road I took an accurate count of the number under my charge, and the following was the result: Standing Rock Indians 64 men, 102 women and children, 138 ponies; Cherry Creek Indians 13 men 42 women and children, 44 ponies; [total] 77 men, 144 women and children, 182 ponies.

The Cherry Creek Indians belong to the agency (Hump and family included) and joined the column at Cherry Creek at the start.

Very respectfully, Your obedient servant, [signed] H. E. Hale, Second Lieutenant Twelfth Infantry.[1]

Captain Hurst expounded on their undertaking in his report to the department adjutant general submitted two weeks later.

Believing that affairs at the Indian dancing camp at mouth of Cherry Creek and at Big Foot’s camp farther up the Cheyenne River, S.D., were assuming an alarming character, I ordered Lieut. Hale, 12th Infantry, to proceed on the morning of Dec. 18, 1890, rapidly to mouth of Cherry Creek, and remain there or in that vicinity until further orders, observing, directing and reporting any movements that might occur. After promptly and frequently reporting the situation as he found it and the result of his observations, he reported to me in person during the night of the 20th ultimo direct from Cherry Creek that there was a large party of Sitting Bull’s people just arrived on Cherry Creek, many of them armed, but that he thought that they could be induced to surrender and come into the Agency here. At daylight next morning I started with him on his return to Cherry Creek accompanied by Sergt. Philip Gallagher, Co. A, 12th Infantry and two enlisted Indian scouts who spoke English and acted as interpreters for the purpose of disarming these Indians and bringing them into the post.

We arrived at mouth of Cherry Creek at 3:30 p.m. same day, distance from Bennett 52 miles. In a very brief interview with these Indians immediately upon my arrival, I told them what I had come to them for, and that as I was very tired and hungry, I would have a council with them after they had a feast, for which I purchased two beeves and turned them over to them.

Upon a hasty and close observation of these Indians, I believed I could induce them to come quietly into the post, and apparently paid no attention to them until they indicated that they were ready to talk, which they did at about 8 p.m. At that hour I met their principal men and all in council, for which I had provided a liberal quantity of smoking tobacco. They told me that they had left Standing Rock Indian Agency never to return, that their great chief and friend Sitting Bull had been killed without cause, and that they had come down to Cherry Creek to talk with their friends there, and had found them suddenly gone, and that they had not fully decided upon their future course. I replied and said that I had come to them as their friend, and that I wanted them to believe and trust me, and that I wanted them to give up their arms to me that night and to return with me to Fort Bennett next morning, where they would be provided for and taken care of, that I could give them no promises as to their future disposition and could only assure them of present protection if they trusted me, but that if they chose to join Big Foot, who was only ten miles up the river, the result would be the certain destruction of themselves and probably their families, and that I had nothing more to say to them.

They said they would soon tell me the result of their deliberations and at midnight they came in a body and delivered up to me all the guns they said they had–seventeen in number and twelve Winchester cartridges. I told them I was sure they were not acting honestly, and that they were not giving up all their arms, but not being in a position to dictate measures, I quietly received such as they gave me–four guns were found secreted among their baggage on arrival at Bennett, making 21 guns taken from them.

Broke camp at daylight on the 22nd ultimo and camped that night at Dupree’s ranch, where we found Colonel Merriam’s command also in camp.

I had sent early in the morning one of the scouts with me to the Agency and Fort Bennett, with request to send out to Dupree’s ranch that night to meet us, all the wagons that could be forwarded to aid in getting these people quickly to the post and at midnight they reported to me. Early next morning, the 23rd instant, I received an order from Colonel Merriam, 7th Infantry, to proceed immediately to Fort Bennett, resume command of the post, turning over the Indians to Lieut. Hale. Copy of the order appended marked “A”. I appealed in person to Colonel Merriam to let me remain with these Indians until their arrival at Bennett, for I feared the result of a sudden scare or panic among them, with Lieut. Hale absolutely alone, as the Colonel’s order took from him the two enlisted Indian post scouts, and the only soldier accompanying us. He considered it more important for me to proceed to the post, where I arrived at 3:30 p.m. same day, having travelled 106 miles since leaving the post.

Next day, the 24th ultimo, Lieut. Hale and the Indians arrived at about 5 p.m., and went immediately into camp by themselves on the river bottom below the post. The Cherry Creek Indians with them were allowed to go to the camp of their own people next day. The Standing Rock Indians, augmented by some that had joined them here, were transferred to Fort Sully on the 30th ultimo as military prisoners, by orders of the Department Commander, numbering 227,–81 men, 42 boys, 72 women and 31 girls–148 ponies and 4 wagons, for which the Commanding Officer Fort Sully receipted.

Attention is respectfully invited to report of Lieut. Hale accompanying this and marked “B” and to the prompt, efficient and important service rendered by him in this connection during the period from the 18th to the 24th ultimo, both inclusive.

I desire also to commend the very efficient and zealous service of Sergeant Gallagher and the two enlisted scouts, who, with Lieut. Hale and myself started out on this expedition without the burden of rations or blankets, knowing that whatever success attended it must be accomplished quickly.

Very respectfully, Your obedient servant, [signed] J. H. Hurst, Captain, 12th Infantry, Commanding Post.[2]

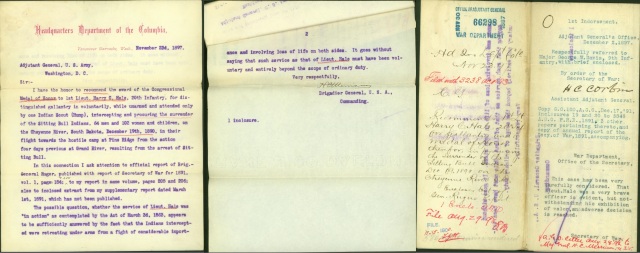

Captain Hurst, by direction of the department adjutant general, submitted a report the following March of what he deemed was, “Gallant and specially meritorious conduct in service.” In addition to commending Lieutenant Hale and Sergeant Gallagher, Captain Hurst rightfully included his own name and actions. General Ruger endorsed the recommendation making no mention of Sergeant Gallagher causing the Adjutant General’s Office to return the recommendation in September for clarification. General Ruger explained that he recollected, “It did not appear that Sergeant Gallagher performed any personal act considered by itself as specially meritorious, or any duty independently of the presence of his officers.”[3]

![(Click to enlarge) Report of gallant and specially meritorious conduct of Captain Ezra P. Ewers, Captain Joseph H. Hurst and Lieutenant Harry C. Hale.[4]](https://armyatwoundedknee.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/hurst-recommendation1.jpg?w=623&h=285)

(Click to enlarge) Endorsement to Captain Hurst’s report of gallant and specially meritorious conduct .[4]

For… conspicuous courage skill and fortitude displayed by him in the execution of the orders of his Post Commander in proceeding rapidly, (Dec. 18th) to Cherry Creek, S.D., observing and promptly reporting the movements of the above named hostile band–and (Dec. 20) riding up, unarmed and accompanied by the only white man there, to Sitting Bull’s band of hostile Indians, direct from the scene of their Chief’s death, and by his courage and tact retaining them at that place for 24 hours, until he could make good his promise for supplies–which he did after a ride of 104 miles to Ft. Bennett and return, making a continuous ride of 52 miles in six and a half hours, and bringing about the immediate surrender of these Standing Rock Indians, together with a large number of Cherry Creek Indians, and their arms.[5]

The final commendations for both officers, in keeping with the practice of the day, were pithy and devoid of most detail.

December 6 to 24, 1890. 1st Lieutenant Harry C. Hale, 20th Infantry (then 2d lieutenant, 12th Infantry): For conspicuous courage, fortitude, good judgment, and tact in dealing with the hostile Sioux Indians at their ghost-dance camp near the mouth of Cherry Creek, South Dakota, which resulted in the surrender and disarmament of a large band of them.

December 18 to 24, 1890. Captain Joseph H. Hurst, 12th Infantry, commanding Fort Bennett, South Dakota: For courage and good judgment in dealing with a band of hostile Sioux Indians, followers of Sitting Bull, at Cherry Creek, South Dakota, detaching them from other hostile Indians, and conducting them to Fort Bennett, where they were disarmed.[6]

Captain Joseph Henry Hurst was retired for disability in 1893 and died three years later at the age of fifty-nine.

Seven years after Lieutenant Hale’s actions during the campaign, Brigadier General Henry C. Merriam, Commander of the Department of Columbia, recommended that Lieutenant Hale be awarded a Medal of Honor for his actions in inducing the Sitting Bull Indians to surrender without a fight. During the campaign, General Merriam was serving as the commander of the 7th Infantry Regiment and had overall tactical command of Captain Hurst and Lieutenant Hale. Recognizing that no active combat occurred during the course of the surrender of arms and subsequent march from Cherry Creek to Fort Bennett, General Merriam placed the recommendation in the context of the skirmish following the arrest and death of Sitting Bull; he stated, “The possible question, whether the service of Lieut. Hale was ‘in action’ as contemplated by the Act of March 3d, 1863, appears to be sufficiently answered by the fact that the Indians intercepted were retreating under arms from a fight of considerable importance and involving the loss of life on both sides.” The Secretary of War denied the recommendation on 17 December 1897 writing, “That Lieut. Hale was a very brave officer is evident, but notwithstanding his exhibition of valor, an adverse decision is reached.”[8]

(Click to enlarge) Brigadier General H. C. Merriam’s 1897 recommendation that Harry C. Hale be awarded the Medal of Honor.[9]

Harry C. Hale rose to the rank of Major General and commanded the 84th Division during the Great War. In 1922 he took command of the 6th Corps Area, a later version of the frontier Army’s Division of the Missouri based in Chicago. He retired by law in 1925 on his sixty-fourth birthday. His West Point obituary, regarding the disapproval of the Medal of Honor, stated, “the very feature of his accomplishment that made it remarkable barred the award. Though his life was in imminent danger, with the Indians virtually on the war-path heading for Wounded Knee, no shot had been fired, and the essential element of combat was therefore lacking.” Major General Hale died in 1946 and was buried in the Arlington National Cemetery next to his only wife, Elizabeth, who predeceased him by four decades.[11]

Harry C. Hale rose to the rank of Major General and commanded the 84th Division during the Great War. In 1922 he took command of the 6th Corps Area, a later version of the frontier Army’s Division of the Missouri based in Chicago. He retired by law in 1925 on his sixty-fourth birthday. His West Point obituary, regarding the disapproval of the Medal of Honor, stated, “the very feature of his accomplishment that made it remarkable barred the award. Though his life was in imminent danger, with the Indians virtually on the war-path heading for Wounded Knee, no shot had been fired, and the essential element of combat was therefore lacking.” Major General Hale died in 1946 and was buried in the Arlington National Cemetery next to his only wife, Elizabeth, who predeceased him by four decades.[11]

Endnotes:

[1] Harry C. Hale, Report to Post Adjutant, Fort Bennett dated 26 Dec 1890 from Report of the Secretary of War Being part of the Message and Documents Communicated to the Two Houses of Congress at the beginning of the First Session of the Fifty-Second Congress, vol. 1 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1892), 200-201. In the annual report, the transcription of Hale’s report records his middle initial as “E,” not “C.”

[2] Ibid., 201-202.

[3] Adjutant General’s Office, Honorable Mention file for Joseph H. Hurst and Harry C. Hale, Principal Record Division, file 3466, Record Group: 94, Stack area: 8W3, Row: 7, Compartment 30, Shelf: 2. Research conducted by Vonnie S. Zullo of The Horse Soldier Research Service.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] L. D. R., photo., “Capt Joseph Henry Hurst,” FindAGrave (http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=90041159), uploaded 13 Jul 2012, accessed 2 Dec 2015.

[8] Adjutant General’s Office, Appointment, Commission and Personal File of Harry C. Hale, Principal Record Division, file 3238, Record Group: 94, Stack area: 9W3, Row: 20, Compartment 6, Shelf: 5. Research conducted by Vonnie S. Zullo of The Horse Soldier Research Service.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] “Harry C. Hale 1883,” West Point Association of Graduates Memorial Articles (http://apps.westpointaog.org/Memorials/Article/3004/), accessed 3 Dec 2015.

[12] D. Nelson, photo., “Harry Clay Hale,” FindAGrave (http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=44967872), uploaded 30 Nov 2009, accessed 2 Dec 2015.

Citation for this article: Samuel L. Russell, “Captain Joseph Henry Hurst and Lieutenant Harry Clay Hale, 12th Infantry – Courage, Fortitude, Good Judgment, and Tact,” Army at Wounded Knee (Carlisle, PA: Russell Martial Research, 2015-2016, http://wp.me/p3NoJy-Ra) posted 20 Dec 2015, accessed date __________.

I have found your “dispatches” very interesting. And I hope that you are getting a book together. I am sure it will be successful.

A very happy Christmas, and a healthy, successful New Year

Warmest regards

Susan

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLike

Thank you, Lady Griffiths. Have a wonderful Christmas.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Lenora's Culture Center and Foray into History.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Sam Russell.

Thank you for visiting my blogcasa and for reading “Trust and Survival” in AIQ.

Questions:

Have you come across any collections of Hurst’s or Hale’s personal correspondence?

Have you done any research in the “old army” records at NARA DC regarding Hurst or Ezra Ewers?

Have you ever found any mention of Wounded Knee–outside of the military records generally cited–by Miles?

Yes, my hunting/research expeditions continue.

It’s a fishing expedition for “I’ll know it when I read it” information. 🙂

Thank you.

LikeLike

Mr. Russell: I enjoyed your article on Joseph Hurst and Harry Hale. I am a grandson of Harry Hale’s nephew, Maj Gen Willis H. Hale, who served as Harry’s aide in China and with the 84th Div at Camp Zachary Taylor, and with Harry in France with the 84th and 26th Div’s, and who commanded the 7th Air Force in the Pacific during WWII.

I saw you have read Eva Wojcik’s article. She and I corresponded briefly and I think she was doing more research on Capt. Hurst, who as you may know, later figured in the birth of the Earp/Clanton confrontations in Tombstone.

Anyway, this was a nice article with interesting documentary support. Thanks,

Dave Nelson

LikeLike

Sam.

I’m counting Standing Rock Indians at 227 total and the Cherry Creek Indians at 77. Combined that would be 304. Is that correct? Also, I’ve received word that Harry Clay Hale’s name has been forwarded on to the U.S. Army for consideration for a posthumous Medal of Honor.

LikeLike

Cheryl… The numbers provided by Hale and Hurst are a bit confusing, primarily because they reported them in different formats.

Hale: “On the road I took an accurate count of the number under my charge, and the following was the result: Standing Rock Indians 64 men, 102 women and children, 138 ponies; Cherry Creek Indians 13 men 42 women and children, 44 ponies; [total] 77 men, 144 women and children, 182 ponies.”

Hurst: “The Cherry Creek Indians with them were allowed to go to the camp of their own people next day. The Standing Rock Indians, augmented by some that had joined them here, were transferred to Fort Sully on the 30th ultimo as military prisoners, by orders of the Department Commander, numbering 227,–81 men, 42 boys, 72 women and 31 girls–148 ponies and 4 wagons, for which the Commanding Officer Fort Sully receipted.”

Counted another way, Hale reported 166 Standing Rock Indians (men, women, and children), and 55 Cherry Creek Indians (men, women, and children). Hurst did not provide numbers for the Cherry Creek Indians, stating only that they returned to their camp. He counted 227 Standing Rock Indians (men, women, and children), which is 61 more than Hale counted en route. Hurst indicated that additional Standing Rock Indians joined them “here” (I assume Fort Bennett). I understand that only the Standing Rock Indians were held as prisoners.

I have not heard about Hale’s MOH being reconsidered. I am not a proponent of readdressing medal recommendations once they have been duly considered in the era in which they were recommended. I agree with the exceptions to right wrongs created by prejudices of the time–such as minorities who weren’t given due consideration because of existing biases when they served–but not as a means of “rewriting” history.

The most prominent case being that of President Theodore Roosevelt. His recommendation was duly considered by the MacArthur board in 1899 and was not forwarded to the Secretary of War because the board determined that, while gallant, his actions did not rise above that of his peers on the battlefield, a requirement that was specified by Secretary Alger. A century later, he was awarded the medal, which I believe should never have been reconsidered. The case was only taken up again because of who he became after San Juan Hill, and, I would argue, was awarded because of who he became, not because of what he did.

LikeLike

Did you receive the pictures ?

LikeLike

Sam, In most cases I would agree with your assessment of not going back over ground that had been covered, but I believe Hale may have been caught in the controversy that swirled around the Medal of Honor being awarded to many who took part in Wounded Knee. Hale had the backing of his superior for the Medal and two generals at the time. It wasn’t a case of a well-known political figure in his case.. But this may be a moot point. Since I first heard about the possibility three or four months ago I haven’t heard anything more/. Cheryl

LikeLike

Cheryl… It certainly is a fascinating case, and I share in your enthusiasm surrounding Hale’s and Hurst’s efforts. You mention a controversy swirling around the Wounded Knee medals. Any controversy is only about thirty or forty years old. It certainly was not a controversy during the lifetimes of those awarded or recommended. There was no controversy through at least the first half of the 20th Century. Capt. Charles Varnum was awarded his medal in 1897, less than a year before the final consideration of the recommendation to award Hale. Further, the War Department continued to bestow medals for decades after the Hale recommendation was disapproved. Varnum was also awarded a Silver Star Citation for Wounded Knee twenty years later. Sedgwick Rice was awarded a Distinguished Service Medal in 1918, and Harry Capron and John Hoff were awarded Distinguished Service Medals in the 1930s. I have heard anecdotally that one of the first Purple Hearts ever awarded was bestowed on an old veteran who was wounded at Wounded Knee, although I have been unable to corroborate any record of that. Incidentally, the only controversy in the media during the 1890s that I have found surrounding honors for the 1890-’91 Sioux campaign was regarding the War Department’s refusal to recognize certain officers that the Midwesterners felt were deserving of accolades, e.g., Fechét, Forsyth, and Whitside. The Omaha Bee wrote in December 1891 regarding General Orders that recognized so many soldiers, but failed to recognize individuals who many felt were deserving.

I certainly would be interested in any further information regarding Hale’s case that you may come across.

LikeLike

Hi,my name is Dan and I have a strange twist to this article.I live in the Pocono’s and just purchased a pair of gauntlet cuffs at a local flea market. On inspecting the brass eagle buttons on the cuffs I found they were Goodwin Patent July 1876 just weeks after Custer’s stand.The button’s were special issue only to Indian War Staff Officers.

This by it’s self is not much. On the Cuff’s there was a blue patch backround with a shield in gold thread. In the shield in silver thread is the number 12.

This may not sound like much to most but the Riding Cuff’s were from a Staff Officer in the 12TH Infantry Regt during the Plains Wars that was at Pine Ridge in Dec 1890.I believe your HARRY C. Hale was a 2nd LT WITH THE 12TH. Ipurchased the Cuffs from a couple from Allentown PA.i BELIEVE YOU h.c.hALE WAS WITH THE pa. 141 vol.

I have the Cuff’s and hope to hear from you if you see the similarities.

LikeLike

Dan,

I can’t authenticate the cuffs. You may want to keep them but if you want to part with them I’d be interested. I started out doing research on Hale because he was a friend of my grandfather’s and my mother spoke highly of him. My grandfather was given a pistol of Hale’s which we still have in the family. I gave the pistol to my brother who was fascinated by it. He died of ALS but before he died he asked me to write a book on Hale. Unfortunately there were several missing missing pieces that I didn’t have the resources to locate. Also Hale’s military records were destroyed in a fire at the St. Louis archives. Hale fascinated me but I could only go so far. I hope some day Hale will get the attention he deserves.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Cheryl, thank you for response. The question or comment about the cuffs is more about my understanding the events of Wounded Knee and how the 12th Infantry was involved,and at what locations on the Pine Ridge Res.

I take from reading the 12th were stationed at Fort Sully. Do you know the number of men and officers or where to look for information ?

The Cuffs are a true historic oddity. I was able to figure out alot of information by the Patent date of Buttons and # 12. Capt Hale would have joined the military about 100 miles from my home.

I can’t help but think there is a connection. If I were able to reach you I would send you a photo.

I had no idea there were so many different bodies of people spread over the area.I think most people believe like I did,it was a single location at a single Fort.

Thank you for your response, please let me know if you wish to see a photo of the Cuffs.

DAN

Morning Col Russell,how do I upload photos ? Caught my mistake on names as I hit send.

LikeLike

Regarding the 12th. They were transferred from Fort Niagara to take the place of another army unit. They sailed across the Great Lakes then went by train and probably a number of ferries up to Fort Sully. I believe Hale arrived at the fort sometime later and then was transferred to Hurst’s command post seven miles up river.

LikeLike

Dan… Thank you for the comment. The gauntlet cuffs are an interesting find. Of course, it was Joseph Hurst of the 12th Infantry who had earlier served in the 141st Pennsylvania Volunteers. Hurst was born in England and the first U.S. record I have of him is when he enlisted in the 141st Pa. Vols. in Bradford Country, PA, on 7 Aug 1862 as a sergeant in company A. He was promoted to 1st Lieut. on 16 Feb 1863, to Capt. on 21 Apr 1865, and was mustered out on 28 May 1865 at Washington, DC. Following the war, he was awarded brevet promotions to 1st Lieut. and Capt. on 07 Mar 1867, the former for gallant service at Chancellorsville, and the latter for gallant service at Spottsylvania. Hurst’s mother and a younger sister died in 1855 and 1860, respectively, and were buried in Bradford Country, PA, which indicates that the whole family emigrated to Pennsylvania sometime before the war.

Henry Hale wasn’t born until 1861 and was a native of Knoxville, Tennessee. I really don’t see any connection between Hale and the gauntlets, but you may have a case for Hurst.

Would you care to share a photograph of the gauntlets?

Regards, COL Sam Russell

LikeLike

Hale was not born in Knoxville. There is another Hale, with the name of Henry, that came from Tennessee. Hale was from Illinois. Grew up there and was the youngest member of his class at West point. His father’s name was Judson T. Hale.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cheryl… Thank you for the correction. As I have gone back through my source documents, Harry Clay Hale was born in Knoxville, Illinois, rather than Tennessee.

LikeLike

Hi will send photo’s in a second. Not sure of any link to Hale but do think a Staff Officer

of the 12TH Infantry at Pine Ridge had these made before or perhaps after Wounded Knee.

All the materials used are period correct and the cost to make would be in the hundreds.Each button is worth over $20. It’s just a thought that you will recognize the patch,the Buttons were issued to Staff Officers during Plains Wars date July 1876.

LikeLike