Little Wound’s face grew black. I could see the men tighten their Grasp upon their knives, and knew that my life was in the balance.

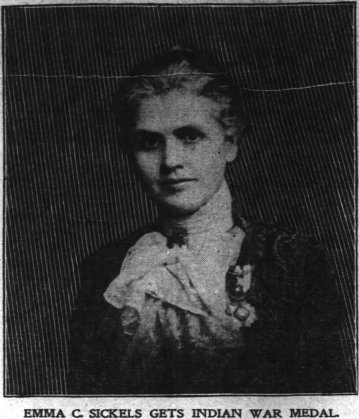

Breaking from my general theme of this site, I have chosen to write about an individual who was not present at Wounded Knee, was not a soldier, and was not in the employ of the government. Hours of research sometimes are rewarded with a first hand account of a significant event that has seemingly gone unnoticed by other historians. Lieutenant John Kinzie’s account of Wounded Knee was one such example. The account of Emma Cornelia Sickels, a thirty-six-year-old native of Massachusetts, appears to be another.

While researching individuals detailed in a compilation of Omaha Bee articles that I am preparing for publication, I came across references to Emma Sickels. The article was from January 1896 and detailed that Miss Sickels of Chicago was awarded a gold medal from a society in France. The article went on to state:

When the uprising occurred in 1890 she volunteered her services as a mediator to the War department. Secretary Proctor and General Schofield sanctioned her enterprise. She managed at great personal risk to get into the camp of the hostile Indians, and although the massacre of Wounded Knee took place, she has always maintained that by giving General Miles timely information of the intentions subsequent to that she averted a wholesale slaughter at the agency.[1]

The medal she received, either in 1896 or 1902, was described as a gold medal shaped like a sunburst, and engraved on the reverse, “To Emma C. Sickels, the Heroine of Pine Ridge; for exceptional bravery in checking the Indian war of 1890.”[2]

The medal she received, either in 1896 or 1902, was described as a gold medal shaped like a sunburst, and engraved on the reverse, “To Emma C. Sickels, the Heroine of Pine Ridge; for exceptional bravery in checking the Indian war of 1890.”[2]

Of all that I have read on Wounded Knee, her name did not register. After searching through a plethora of books on the subject, from Greene’s American Carnage to Utley’s Last Days of the Sioux Nation, and from Coleman’s Voices of Wounded Knee to Jensen, Paul, and Carter’s Eyewitness at Wounded Knee, I came up with little that would merit the accolades detailed in the Bee article. Greene made no mention of Miss Sickels, and Utley and Coleman only briefly quoted her with a disparaging characterization of Pine Ridge Indian Agent Daniel F. Royer. Jensen, Paul, and Carter provided a lengthier quote where she described the home of Red Cloud. Other than those brief entries, current historians covering the Sioux disturbances of 1890 and 1891 paid her little or no attention.[3]

Always preferring primary sources over secondary, I dug into those authors’ end notes. The reference that Utley and Coleman cited was to a lengthy letter that Brigadier General Leonard W. Colby of the Nebraska National Guard included in his work “The Sioux Indian War of 1890-’91.” Sickels wrote to Colby at his request in the middle of January 1891 from Pine Ridge when the outbreak was just being brought to a peaceful settlement. I found it interesting that Miss Sickels did not stop at Dr. Royer and provided her low opinion of Brigadier General John R. Brooke as well. “General Brooke is unanimously, and justly, characterized as obstinate, short-sighted and easily deceived.” She went on to say, “He was one who knew about facts after they had happened, and seemed to be constructed so that he was mentally incapable of anticipating or preventing any event.” Sickels continued her scathing attack on Brooke and seemed to lay much of the blame for Wounded Knee at the general’s feet.

The Seventh Cavalry was rescued by Colonel Henry without orders from General Brooke. No defense of fortifications or outlying sentinels had been placed around the agency. Only through the services of Major Cooper was it possible for those to act who defended the Agency and prevented a massacre. I am stating these facts plainly to show why there is so strong a feeling against a man who, by his criminal inaction placed so many lives in danger, which he was employed to defend, by permitting the plots to be carried on in spite of warning, by allowing preparations for hostilities to be publicly made at the Agency blacksmith shop, and by depending for his information upon those only who, to say the least, were of very questionable character. His command to Colonel Forsythe was: “Disarm them; if they resist, destroy them!” I have been told that there is written evidence of this.

The attack of Big Foot’s band was premeditated and skillfully planned. If it had been successful, those who have been in readiness to join the uprising in their different places along the line from Texas to Montana, would have broken out.

Although we may justly condemn the lack of discretion that would forcibly disarm them while their worst feelings were aroused, creating a resistance consistent with all ideas of manliness and bravery (in which the Indians have never been deficient), yet this has been overruled for good by showing the opposing forces their mutual power and spirit. As one of the Indian boys wrote in language work at the school: “Indians laugh when white soldier comes. They think he cannot fight, and cannot hurt them; but white soldier fight strong and Indian man now think it not easy.”

On the other hand, the desperation and bravery shown by a body of one hundred and fifty men who will attack five hundred who have surrounded them, show the spirit of the foe our soldiers had to meet, and should convince a skeptical nation of the firm, strong measures needed to be taken.[4]

Miss Sickels was certainly an opinionated woman and not afraid to put it in writing. I found another reference to Sickels in James Mooney’s landmark work The Ghost Dance Religion and Wounded Knee. Mooney was an ethnologist who visited Indian tribes across the country investigating the origins of messiah religions among Native Americans. His laborious work for the Smithsonian Institution was the first real investigation into the causes of the Sioux outbreak and is first on a long list of sources for any work on Wounded Knee. Thus, I was surprised to note that Mooney listed Sickels among his many acknowledgments. He credited her with providing a translated version of Pine Ridge Indian policeman George Sword’s account of the Ghost Dance.[5]

I focused my research on newspapers of the day and was not disappointed. I found numerous articles detailing her award of a medal from the International Society of La Savateur, or more properly Le Sauveteur, of Paris, France. One of those accounts seemed to lean toward self-aggrandizement and left me wondering if Sickels gave more weight to her own actions than was warranted.

Gen. Miles was about to order an attack upon the Indians when I informed him of their suspicions and told him that if I went out and explained how the battle of Wounded Knee came to be fought I thought they would come in peaceably. The general consented to delay the attack. I went into the Indian camp, explained matters to the chiefs, and came out unmolested. A half hour later the hostiles were in the agency and the uprising was at an end. The United States government appointed me the commissioner in charge of the Indian exhibit at the Columbian exposition as a part recognition of my work.[6]

Many of the articles referred to Miss Sickels as the “Heroine of Pine Ridge,” and I wondered if the title was self-proclaimed. Further research revealed a lengthy article published in the Chicago Tribune on December 21, 1890, prior to the Wounded Knee affair, detailing her success in bringing one of the key Lakota chiefs back into the camp of friendly Indians at Pine Ridge, and I was prepared to present that article here. Then my research came on a more detailed account that Miss Sickels published in April 1893 in The National Tribune. It is a riveting narrative of a brave woman determined to do everything within her power to bring a potential Indian war to a peaceful conclusion even at the cost of her life. If true, it is a remarkable feat of peaceful intervention. Unfortunately, it cannot be corroborated with any other first hand account, which may be why modern historians have left the story of Miss Emma C. Sickels to the archives. Either that, or her role has been all but overlooked.

Among the Sioux:

A Woman’s Experience During the Pine Ridge Troubles.

One of a party of five ladies en route from Chicago, I left the railroad at Valentine, Neb., Dec. 2, 1884, for an overland ride of 150 miles to Pine Ridge Agency. The wintry journey over the unbroken prairie was full of incident and experience only found on such a trip. To-day the whirl of farm houses and villages seen from the comfortable Pullman has taken the place of the boundless monotony, varied only by creeks, prairie-dog towns, and the slopes of the surrounding ridges. The mule-train, ambulance and pack-wagon have given way to the swift-moving train. A dining-car offers a far different bill of fare from the meals cooked upon the camp-stove, which we enjoyed with keen appetites in our tents, pitched by the creek, in the shelter of the cliff; and the blizzard which challenged our right to enter the country would now be powerless in wreaking the wrath it then poured upon its helpless victims.

No pains had been spared by Agent McGillicuddy and his wife for making us comfortable—relays of teams, supplies of well-cooked food, well-furnished tents and careful attendants had been provided; Mr. McGillicuddy himself taking charge of the expedition. We were well taken care of when we reached the Agency—white people and Indians seeming to conspire to make us contented with our new home.

As Superintendent of the large Government Indian boarding-school, I had full opportunity to become acquainted with the leaders of the Sioux, and learned their respective ability and influence, the relative power and characteristics of their bands.

I became much attached to them, and when I resigned my superintendency to resume the study of my profession in Chicago, I was much gratified to learn that the Indians had held a council and wished me to return to again take charge of the school. Although it was impracticable for me to go, their action was valuable to me as a token of confidence and good will.

On Dec. 2, 1890, I started again for Pine Ridge, from Washington, alone, on a very different mission. I went, authorized by the War and Interior Departments, fully informed by the officials of the extent of the threatened outbreaks and causes of apprehension of danger, to do what I could toward ascertaining the facts and restoring the confidence of the disaffected Sioux.

This was of great importance, because as the General of the Army told me, “on account of the distrust and uncertainty it was impossible to obtain reliable information, and consequently the greatest obstacle in the way of peace was the lack of the necessary discrimination between the hostiles and those well disposed.”

The newspapers were full of an Indian outbreak; Cabinet meetings were occupied in discussing the situation. All topics on the floor of Congress yielded to this; the Sioux reservations had been placed under military control; soldiers had been ordered from their distant posts; full preparation was being made for extensive warfare.

My knowledge of those who were accused of being the instigators of the trouble convinced me that there must be some grave injustice, some gross misunderstanding, which should be investigated.

None knew better than I the personal danger which I would incur, but as I had said to Secretary Proctor, he had not hesitated to send 6,000 soldiers to risk their lives in war, I was ready to risk mine in the interests of peace. I made preparation, in case I should never return, and started, by a singular coincidence, on the anniversary of my first journey.

Trains bearing soldiers to the scene of action passed those loaded with men, women and children fleeing from the danger.

Leaving the railroad at Rushville, Neb., I rode about 20 miles by stage to my former home, and was welcomed by my old friends.

At the Agency all was uncertainty and suspense. Each day brought new rumors of war and preparations for hostilities. It was impossible to tell the false from the true, except by personal knowledge of the character of the informants.

Little Chief, the redoubtable leader of the Cheyennes, was camped with his band on the South. He had been compulsorily sandwiched among the Sioux for about six years. The previous Summer he had attempted to make his escape to his home in Montana—requiring the military to bring him back. He was consequently in good fighting mood, and was preparing to use this opportunity. Near him were encamped a heterogeneous number of “orphan and loafer” camps. Red Cloud and his men lived on the northwest, having been a constant center of disturbance since the Agency was established.

The Brule-Sioux were intrenched in the impregnable “bad lands” about 40 miles distant, and Little Wound—the one universally credited with being the pivot of action—was encamped with his men on Wolf Creek, about four miles away.

My acquaintance with the Indians enabled me to get at the facts. I became convinced that the real hostiles were at the Agency, and were decoying the soldiers into an attack upon the Brules and Little Wound, thus leaving the Agency unprotected, at the mercy of those who would seize it as a center of operation.

My knowledge of Red Cloud, gained from personal experience; his methods; his system of communication with different tribes, of which I had been informed from various sources; the coincidence between the presence of his messengers and the manifestations of hostilities even in remote tribes, and his movements at the Agency, furnished me the clews. I knew that he had deadly hatred for Little Wound; that the latter had frustrated many of Red Cloud’s plots. I traced the reports of Little Wound’s hostilities to the interviews so freely given by Red Cloud and his men to reporters, and was confident that if Red Cloud could involve the progressive Indians, conceal his own complicity, and settle a score with an old enemy—whose father he had killed—that he would deem it worthy of his utmost efforts. Such a course would be consistent with his whole career of treachery and disorder. This conviction was borne out by subsequent events. I was determined to see Little Wound, carry to him the messages of peace with which I had been commissioned, and learn his grievance.

After much difficulty in obtaining horses I started for Little Wound’s camp with two of my former pupils—young men—members of Little Wound’s band. My only safety lay in my defenselessness, going to the camp as a friend, attended only by two of his followers.

I found the Chief with a few of his men at a log house near his camp, suspicious and desperate, preparing for self-defense with guns and arrows. I should not have respected him had he not, under the circumstances, taken measures to protect his band, who were in hourly expectation of an attack by the soldiers. The girls afterward told me that their mothers lay all night trembling in fear.

I told the Chief that I had not forgotten that when my life was in danger, because Red Cloud wanted to burn down the schoolhouse and kill me, he (Little Wound) had brought his men and saved our lives. I had heard that now my old friends were in danger, and I had come with messages from the great men in Washington, who wanted to know what the trouble was, and what could be done to stop it.

He said that his people had been sick; that they had but little food, as the crops had failed; there was no feed for the ponies; instead of the payment of $100,000, which had been promised that year, in fulfillment of the treaty they had been compelled to sign, there was 1,000,000 pounds less of beef than before, and all the people were in great trouble.

I told him that I had read in the newspapers that he was making war. He replied that “Red Cloud had been getting the Indians into bad ways, and when it was being found out he told all the men who made the papers that I had done it.” He showed me a letter from his grandson at Carlisle, which, he said, made his “heart bad.” It read:

“Dear Grandpa: When I am reading in the newspapers it makes me shamed about what you doing in ghost dancing.”

I asked him to tell me about the ghost dance. He explained that “One white man had said to the Indians: ‘There is one religion—by way of ghost dancing, which would help all the Indians.’ I thought if anything would help the Indians I would look to it and see, but I have found that the ghost dancing does not help, and I have put it away.”

The keynote of despair was struck in the words repeated by Yellow Hair, Little Wound’s Lieutenant: “All the white folks think that we are all bad.” This was repeated over and over by different ones during the interview.

I replied that bad white folks and bad Indians had been keeping the others apart and getting them into trouble, but if now the best people of both races could be better acquainted and work together, we would have the trouble stopped. I had brought words of peace. I would tell everybody about the hard times the Indians were having, and we would work together to stop it. I would write in the newspapers, and I would take back their words to those from whom I had come.

I left the camp and went back to the Agency, to find that there my return had been given up, in the belief that my errand had been fatal.

Their fears were nearly realized the following day when I made my next visit to the camp. The mischief-makers made me the subject of their efforts, fanning the flames of distrust and suspicion.

I found Little Wound and his men on the alert, ready with guns and knives. I told the Chief that I had fulfilled my promise, and wanted to talk with him again.

He went into his tepee, and I heard a clanking sound. I called him and he came out, followed by seven men with guns and knives. He went to a knoll not far away and held another conference. I told him that I had been thinking about the trouble that his people were in, and wished that all the white people knew about it. Would he like to go to Washington and tell those who were there? Little Wound’s face grew black. I could see the men tighten their grasp upon their knives, and knew that my life was in the balance.

Little Wound said: “I have been to Washington many times. It makes me a liar to my people.” I learned afterward that not only had I touched upon the greatest cause of grievance, the bad faith shown the Indians, but that Little Wound, remembering Crazy Horse’s death, believed that I was trying to draw him into a trap.

I asked him if he would prefer to have letters put into the newspapers, and have the white people learn in that way. He said that would be better, and told me what he would like to have written.

Having heard that one of my former pupils was sick, I dismounted and went into her tepee to see her, promising to return the next day and bring her some medicine. I kept my promise, and was able to convince the Indians of my sincerity.

My visit to Little Chief’s camp was but little less hazardous. I invited him to come and see me, saying that I wished to tell him about my mission. He came and in a two hours’ talk gave me full information of his grievance. I could not and did not blame him for wanting to fight, but I told him that I was sure that he would be more successful in gaining what he wanted if he would let the white people know of his trouble and work with them.

This he promised to do, and three weeks later came to bid me good-by as he was starting for this Montana home.

The summary of the whole situation was that the friendly Indians were discouraged, and the hostiles were determined to use this opportunity to carry forward their plots.

Reductions of rations, poor crops, unwholesome food, sickness, failure of treaty payment, had driven the progressive leaders to desperation, while the bloodthirsty, disorderly element had been given prominence.

The “Messiah craze” and ghost-dance songs had their influence, for organizing into a common cause those who wished to gratify their spirit of revenge or love of war.

The Brules at Rosebud Agency had been redistricted by a new survey, throwing their ration center at Pine Ridge. Their coming to Pine Ridge at a time of destitution was resisted by the Ogalalla (Pine Ridge) Sioux, and amid the disorder which followed there were two flights—the flight of Agent Royer in terror for soldiers, and the flight of the Brules to the “Bad Lands.”

The disorderly element, with the treachery common to the worst of humanity (of both races), offered their services as messengers and were accepted, demonstrating that the “greatest discrimination between the hostile and the well-disposed.”

The Brules were told that the soldiers were going to attack them and the military were informed that the Brules were going to make raids upon the settlements. Soldiers were sent with cannon and Gatling guns to the interminable labyrinth of the Bad Lands, where the alkali turrets, varying from 50 to 500 feet, marked ravines that irregularly traversed the country over an area of 100 by 40 miles.

On my next visit to Little Wound’s camp, I invited him to come to see me at the Agency. He hesitated, and with evident suspicion, asked me why I wished him to come.

I told him that he could not possibly run any greater risk in coming to see me than I had been willing to do it, to bring help to his people. Was he not willing to do as much as I? He yielded to this argument and came with his wife to see me.

I had invited the Special Agent to meet him, and during the two hours of his stay, Little Wound became convinced of the peaceable intentions of the Government, returning to his camp reassured.

I became so aroused to the danger threatening the Agency, that I went to report the matter where I was sure it would receive the attention it demanded. A few days after I left, Little Wound came into the Special Agent’s office and volunteered to go to the “Bad Lands” and bring back the Brules, asking for protection in case of trouble, saying that he had gone on a similar errend [sic] once before and had not been supported by the Government. He went to the Bad Lands and was successful in his mission, making the attack by the soldiers unnecessary, thus throwing his power into the balance of peace.

Meanwhile preparations had been going on to capture the Agency. Big Foot’s band, composed of the worst element of Standing Rock (Sitting Bull’s remnant), Cheyenne River and Rosebud Agencies were on their way to Pine Ridge to fight, as I have learned from trustworthy sources.

When it was known that a hostile band of Indians was at large, each settlement felt that it might be the point of attack. Farms and ranches were deserted, all the inhabitants huddling together in the little towns in a most pitiable manner. Squads of soldiers were sent in different directions to intercept and surround Big Foot’s band.

Maj. Whiteside [sic] came upon them about 26 miles from the Agency, and, compelling them to surrender, brought them down to Wounded Knee Creek, where, after supplying needed tents, they encamped for the night; he had sent for reinforcements who arrived about midnight, keeping close guard over the wily hostiles lest they again slip away.

In the morning they were sullen and taciturn. The command had been given to the officer in charge to disarm them at any cost. The order was put into execution. Soldiers, pressmen, and others, with guns unloaded and hands in pockets, stood idly watching—repeating the history of the century—thrown off their guard by the seeming compliance of the Indians, when suddenly the preconcerted signal was given. The Indians, relying upon their medicine men and the invulnerability of their “ghost-shirts,” opened the attack, men, women, and children joining in, and the world has the “Battle of Wounded Knee.”

I have most carefully gathered this information from the survivors of Big Foot’s band; from the Sioux now living at Wounded Knee; from a knowledge of their beliefs and customs; from soldiers, press correspondents, and other sources, and have been able to trace nearly every other version to those who have especial motives for concealing the facts.

Unfortunately, the return of Little Wound and the Brules was coincident with the conflict at Wounded Knee. Excited and designing messengers brought back terrifying reports. The planned attack was made upon the Agency, beginning with the schoolhouse. All was consternation and chaos. The Brules, accusing Little Wound of alluring them to the same fate that had befallen Big Foot’s band, again fled, taking him prisoner as hostage for their safety.

At this juncture Gen. Miles arrived at the Agency and immediately took measures to protect it by sentry earthworks and camps stationed at exposed points.

The valiant services of Little Wound seem not to have been reported to Gen. Miles by the Official to whom the Chief applied for protection. In the confusion the treacherous messengers again offered their services, and were again accepted. Reports were spread that Little Wound and the Brules were defiant hostiles. Soldiers were sent to bring them in, and orders were given setting the ultimatum of a limited time for a voluntary return. Death seemed inevitable to them in either alternative. Big Foot’s band was represented as a company of peaceable travelers brutally shot down by the soldiers in cold blood. The messengers sent to them, as I have since learned, told them that this was to be their fate. Big Road, Red Cloud’s nephew, with a diligence equaled only by his zeal in leading the ghost-dance, brought and carried these reports. But few soldiers were left at the Agency. Nearly all had been ordered where a cordon could be drawn around the hostiles or a barrier placed between them and the frontier towns. The press of the day was filled with stirring reports of these details. All clamored for immediate action against the “hostiles.”

I had reached Chadron, Neb., Dec. 27, expecting to go to Pine Ridge on the 30th. The battle of Wounded Knee occurred Dec. 29. All communication between Chadron and Pine Ridge was cut off. Believing that the plan of the campaign was the same as before, except that the location was changed—Little Wound and the Brules being at Cedar Butte Creek instead of in their former positions—I was determined to go again to the Agency and keep my faith with those who had depended upon my word. I could find no one willing to drive me over to Pine Ridge, and after waiting four or five days went to Rushville, the railroad point nearest the Reservation, and there met Mr. James Cook, well-known ranchman whom Gov. Thayer had requested to go to the scene of danger. With his hand on his loaded gun he drove with me over that desolate road.

Soon after reaching the Agency I learned that my belief was correct that the interrupted plan had been resumed, with the additional incentive of having the chief commander in their power. I reported this to Gen. Miles, and brought to him Yellow Hair, Little Wound’s Lieutenant, who had proven trustworthy. A message was sent which Yellow Hair conveyed to his chief.

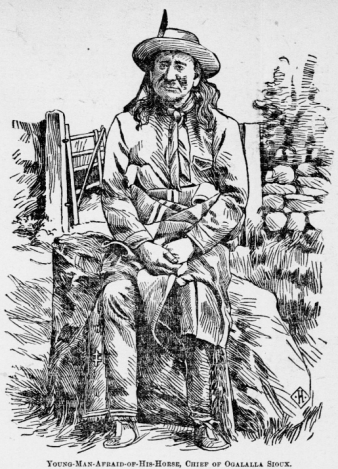

On that day the plan of the campaign was changed. The defense upon the south was strengthened, orders were given that the Agency should be the center of action, and that the troops should concentrate there. Trustworthy messengers were sent for the reassurance of the Brules, among them the Chief Young-Man-of-Whom-Horses-Are-Afraid (which is a more correct interpretation of his name.) He had been away on a bear hunt during the trouble, and Gen. Miles had sent for him to return and act as mediator.

Cedar Butte Creek had become the headquarters for all disaffected and terrified Indians. Many were there clamoring for vengeance on the dead at Wounded Knee. Others found here their opportunity for war and disorder. The situation called for greatest skill and wisdom. A false step might at any time precipitate a carnage compared with which Wounded Knee would pale to insignificance.

After two weeks of intense suspense the Indians entered the Agency. The long, moving column of mounted braves, escorting the train of wagons, was mistaken by old Captains for United States cavalrymen. The young men came in determined to fight.

The friendlies were told that if they did not join in the fight they would be attacked by the soldiers on one side and by the hostiles on the other. None were in greater danger than these unhappy people, who, through no fault of their own, were the victims of so much misfortune; whose pathetic cry had been “All the white folks think we are bad,” and who too fully realized the hostile taunt, “The white man knows no difference—you might as well join in the fight”; showing again that “lack of discrimination” would mete out a common fate to all.

When the moving mass had settled, a dead calm fell upon the Agency—the tense suspense was relaxed.

My knowledge of the Indians made me especially solicitous at this time. The white man excels in power, the Indian in subtlety; and both say, “All is fair in war.” I was anxious to go down into the camp and learn by observation and question the exact situation.

One of my former pupils offered to escort me. The horses had been brought, and I started in search of my companion. On my way I was struck with the desertion of the streets. Few people were in sight, except here and there a group of Indians, the majority of whom were opposite Headquarters, which were separated from them by a common fenced in from the road. Passing hurriedly along, my attention was attracted by a movement—the raising of a rifle to take aim. Following the direction of the aim, I saw Gen. Miles sitting upon the veranda of Headquarters, listening to the music of the military band.

The terrible consequences of a single shot flashed over me. With the hope that I might prevent his action without arousing his suspicion that I mistrusted him, I went to him and asked him if he had seen Marshall (my escort). Instinctively, as I hoped, he leaned to hear my errand, dropping his gun upon his arm, the others also bending over to listen. His small stock of English and my limited Sioux afforded pretext for gaining time and attracted the attention of those around us.

An unarmed soldier standing near, listening to the band, turned and came towards us.

I do not know exactly what I said, but I sent a message requesting Gen. Miles for an interview in his office, telling the soldier I would wait his return. He must have been impressed with the sense of importance of his errand as he hurried away. I have become hardened to danger in many forms, but preeminent in my memory will always be those terrible moments when I stood there awaiting the movements of soldier or Indian. Before me stretched the overhanging ridges, ominous with threatening cannon and Gatling gun, crowded with thousands of armed men, ready for instant action. Below them, camped along the creek, were the Indians, as at Wounded Knee; many were there, we knew, desperate, reckless, eager for bloodshed.

As I stood waiting Capt. Ewers rode by. I motioned to him; he dismounted and approached me. I asked him who the men were, telling what I had seen. He saw the relative position of the Indian and General. The soldier had delivered his message; my ruse was successful; Gen. Miles was leaving the porch.

Capt. Ewers went toward the Indians, but they put spurs to their horses and were soon out of sight. I believe that they thought that I had sent the soldier upon the quest I had sought of them, and were waiting for me to pass on. May I never again be called to endure such moments as when I stood there facing the Indian with the thought that thousands of lives depended upon my absolute self-control.

The pages of Indian warfare are filled with battles precipitated in this way. History has just recorded a similar conflict from which the smoke had scarcely died away—the combatants emerging with renewed hatred and vengeance, and were now again confronting one another—the one with power, the other with subtlety.

When the soldiers returned and I went to Gen. Miles’s office, I could not trust myself to tell him the circumstances—it was still too vivid for words. I made my proposed visit to the camp the subject of my call. With my escort I went among the hostiles and had opportunity for observation.

This was the last afternoon of the outbreak. Conciliatory measures were used to restore peace, and although the brutal murder of Few Tails by white men, and the bringing in of his wounded wife, gave just cause for grievance, the kind treatment she had received at the hands of the soldiers palliated the wrong.

Within two weeks the soldiers had been ordered to their distant homes, the customary delegation of Indians was sent to Washington under the management of an Agent of the Bureau, who knew nothing of the parts taken by the individuals in the “outbreak,” except as he depended upon others for information, and consequently at this crisis “the greatest obstacle in the way of peace” (in the future) was the “lack of discrimination between the hostiles and the well-disposed.”[8]

Born in 1854 in Massachusetts, Emma Cornelia was the fourth child and second daughter of George Edward Sickels. Her mother, George’s second wife, was Maria Louisa, nee Smith. By his first marriage George, a bank clerk, had two sons, George Edward, Jr., and William. George’s first wife, Mary, died in 1847 a few months after William was born. George married Maria Smith in late August or early September 1849 in either Brookline or Westminster, Massachusetts. Together they had four daughters and two boys: Maria Louisa–later Mrs. George A. Tripp–born in 1851; Emma Cornelia, the subject of this essay; Harriet Elizabeth, born in 1855; Ellen Maria, born in 1857; Frederick Henry, born in 1861; and Sheldon Sanford, who died in 1865 in the first year of his life. Maria, the mother, died in November 1865 a few months after her infant son.[9]

Emma Sickels attended college at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary in South Hadley, Massachusetts, graduating in 1872 at the age of eighteen. She moved to Chicago, Illinois, where a number of her siblings and her maternal grandparents were living and pursued a vocation in teaching. Adhering to the social norms of teachers of the day, she never married.[10]

By 1884, the thirty-year-old teacher headed to the Dakota Territory where she spent at least two years working as the superintendent of the Pine Ridge Indian Industrial Boarding School. It was there that she established a rapport with a number of the Lakota chiefs, including Little Wound and Red Cloud. In an 1893 interview, Miss Sickels recounted a dispute between her and Red Cloud, chief of the Oglalas, and her rescue by Little Wound.[11]

I may be prejudiced, but perhaps I am justified, as Little Wound saved my life and the school during the insurrection of 1884. That outbreak was started by my telling the daughter of Red Cloud that if she could not obey the rules of the school she could leave. She was a haughty girl, and left. She went straight to her father, who thereupon made incendiary harangues to his people, denouncing the school and me. After several months he took the field, sided by Little Chief, the fiery Cheyenne. They came down upon Pine Ridge, about a thousand strong, with the avowed intention of burning it and killing me. Dr. McGillicuddy, the agent then, did not believe in military defense, and it seemed as if we were doomed, but Little Wound had heard of Red Cloud’s design, and always having been a friend of mine, he gathered a force twice as strong as the other two chiefs’, and arrived at Pine Ridge the night before the projected attack. Red Cloud saw that he was defeated and sullenly withdrew, and three weeks later sent his children back to the school.[12]

According to a 1910 address by E. C. Bishop, superintendent of Nebraska public instruction, under Miss Sickels’s management the Indian industrial school grew and became a model for other Indian schools. Emma Sickels resigned within a couple of years and returned to Chicago where she furthered her own education and professional pursuits experimenting along industrial and pedagogical lines. She took up educating young women in domestic sciences, that is cooking and housekeeping, and this work took her to New York, where she was engaged at the onset of the Sioux disturbances in the fall of 1890.[13]

Clarence G. Morledge’s photograph “Buffalo Bill’s Indians at P.R. Agency S.D.” was taken on March 2, 1891, and depicts Miss Emma C. Sickels in the center. Major John Burke, manager of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, is kneeling to her right. This photograph was featured in Jensen, Paul, and Carter’s Eyewitness at Wounded Knee, and although Emma Sickels is the center and prominent subject of the photo, the authors of the book made no mention of her.[14]

Following the conclusion of the outbreak, Miss Sickels returned to New York and helped organize Indian exhibits for the New York Press Club and for the Chicago World’s Fair. This led to her taking a leading role in the education of Native Americans serving as Vice-President of the Indian Educational Congress and also as Commissioner for the Indian Exhibit of the 1893 Columbian Exposition. Her propensity to voicing her strong convictions in the press led her into conflict with several leading voices in Indian affairs including Frederic Putnam, director of Indian exhibits, James Mooney, noted ethnologist, and even Thomas J. Morgan, former commissioner of Indian Affairs. Such enemies could help to explain why Miss Sickles’s role during the outbreak received little attention following the actual events, save that of her own articles.[15]

In the latter 1890s, Miss Sickels turned her attentions to agricultural nutrition. She organized and served as the secretary of the National Domestic Science Association and later the National Pure Food Association. She received a patent in 1899 for improvements in the rectification of vegetable oils, principally from maze, offering an alternative to olive oil. Sickels remained active through the 1910s working with Congress on legislation to improve nutrition.[16]

By 1920 her health was failing and she was admitted to the Elgin State Hospital in Illinois. Emma Cornelia Sickels died there on December 13, 1921, at the age of sixty-seven. She was laid to rest at Albion, New York, in the Mount Albion Cemetery where her parents and three of her siblings were buried.[17]

Emma Cornelia Sickels, the Heroine of Pine Ridge, is buried in the Mount Albion Cemetery at Albion, New York.[18]

Photograph from the Chicago Inter Ocean, April 18, 1902.

As for Miss Sickels’s view that Red Cloud was the mastermind behind a grand strategy to converge all the hostile camps onto Pine Ridge for one final decisive engagement, she was not alone in that perception. It was widely publicized in many of the newspapers of the day. Depending on the correspondent, Red Cloud was depicted as in the hostile camp at times and in the friendly camp at others. Clearly Miss Sickels came to Pine Ridge in December 1890 harboring ill feelings toward Red Cloud based on their earlier dispute in 1884 over the chief’s daughter. That explains her willingness to view Red Cloud as the manipulator of that winter’s events. The historical record does not support Red Cloud having much of any role other than that of a very old, nearly blind chief, struggling to keep some semblance of control over events.

Miss Emma C. Sickels’s role has been all but overlooked or ignored by historians of Wounded Knee and the Sioux outbreak of 1890 – 1891. Her efforts at bringing about a peaceful resolution are worthy of further study. In her own time, she was formally recognized as the Heroine of Pine Ridge. It is time that historians recognize her efforts among the Lakota and determine if the title is deserved.

Endnotes:

[1] “Gossip About Noted People,” Omaha Daily Bee (5 Jan 1896).

[2] The Brownsville Daily Herald. (Brownsville, Tex.: 01 May 1902), 1.

[3] Robert M. Utley, Last Days of the Sioux Nation (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1963), 103; William S. Coleman, Voices of Wounded Knee (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000), 88; Richard E. Jensen, R. Eli Paul, and John E. Carter, Eyewitness at Wounded Knee (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1991), 74.

[4] Leonard W. Colby, “The Sioux Indian War 1890-’91” in Transactions and Reports of the Nebraska State Historical Society, vol. 3 (Freemont, NE: Hammond Bros., Printers, 1892), 180-185.

[5] James Mooney, The Ghost-Dance Religion and Wounded Knee (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1973), 655 and 797; originally printed in the Fourteenth Annual Report (Part 2) of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Smithsonian Institution, 1892-93 by J. W Powell.

[6] “Heroine of Pine Ridge,” St. Paul Daily Globe (5 Jan 1896), 14.

[7] Cropped from: “Indian squaws with white family,” Denver Public Library Digital Collections, Western History Collection, call no. X-31366, (http://digital.denverlibrary.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15330coll22/id/24387/rec/1), accessed 19 Mar 2017. Summary of the photograph: “Native American Sioux women wearing dresses, blankets, and hair pipe necklaces and earrings pose outside a porch with a white woman, possibly Emma Sickels (or Sickle,) a white teacher and her three primly dressed children, Pine Ridge Agency, South Dakota.”

[8] Sickels, Emma C. “Among the Sioux: A Woman’s Experience During the Pine Ridge Troubles.” The National Tribune, April 27, 1893: 12.

[9] Carlton E. Sanford, Thomas Sanford, the emigrant to New England; ancestry, life, and descendants, 1632-4. Sketches of four other pioneer Sanfords and some of their descendants, vol. 2 (Rutland, VT: The Tuttle Co., Printers, 1911), 888; Ancestry.com, United States Federal Census [database on-line] (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009), Year: 1850, Census Place: South Reading, Middlesex, Massachusetts, Roll: M432_324, Page: 259B, Image:186; Year: 1860, Census Place: Waukesha, Waukesha, Wisconsin, Roll: M653_1436, Page: 233, Image: 242, Family History Library Film: 805436; Year: 1880, Census Place: Chatham, Morris, New Jersey, Roll: 792, Family History Film: 1254792, Page: 70B, Enumeration District: 116, Image: 0647.

[10] Thirty-fifth annual catalogue of the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, South Hadley, Mass. 1871-72, 13.

[11] Iowa State Education Association, Proceedings of the Fifty-sixth Annual Session of the Iowa State Teachers Association held at Des Moines, Iowa, November 4, 5 and 6, 1910,(Des Moines: Iowa State Teachers Association, 1910), 81-83.

[12] “Red Cloud and Little Wound; Emma C. Sickels on the Careers of the Rival Chiefs,” New York Times (19 Jul 1893), 9.

[13] Iowa State Education Association, Proceedings of the Fifty-sixth Annual Session, 83.

[14] Cropped from: Clarence Grant Morledge, photo., “Buffalo Bill’s Indians at P.R. Agency S.D.,” Denver Public Library Digital Collections, Western History Collection, call no. X-31461, (http://digital.denverlibrary.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15330coll22/id/24387/rec/1), accessed 14 Mar 2015. Summary of the photograph: “Native American Sioux in traditional dress and whites pose on snow covered ground at the Pine Ridge Agency, South Dakota, including: center, Emma Sickels, Pine Ridge teacher, Major John Burke, general manager of Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West show, women, children, a baby carriage and dogs. The water tower and agency buildings show in background.”

[15] Lee D. Carter, Anthropology and the Racial Politics of Culture (Durham, NC : Duke University Press, 2010), 104-111.

[16] United States Patent Office, “Refining Vegetable Oils,” Letters Patent No. 636,860 (14 Nov 1899).

[17] United States Federal Census, Year: 1920, Census Place: Elgin, Kane, Illinois, Roll: T625_375, Page: 20A, Enumeration District: 90, Image: 448; Ancestry.com, Illinois, Deaths and Stillbirths Index, 1916-1947 [database on-line] (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011), FHL Film Number: 1570230.

[18] Karen W., photo., “Emma Cornelia Sickels,” FindAGrave (http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=111032720), accessed 24 Jul 2015.

Citation for this article: Samuel L. Russell, “Emma Cornelia Sickels – Heroine of Pine Ridge or Self-Promoter,” Army at Wounded Knee (Sumter, SC: Russell Martial Research, 2013-2015, http://wp.me/p3NoJy-Jy) updated 19 Mar 2017, accessed date __________.

I did not find this as interesting as some of your previous emails.

I asked some questions in my last email to you?

Best wishes

Susan

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Lenora's Culture Center and Foray into History.

LikeLike

Thank you very much for this post (and all the others).That means for bringing for the contempt women in general, dead or alive, receive from official culturel, for instance historians.

I a french, so I apologize for my broken english. I am also an independent filmmaker and I am preparing a movie which entails a moment about Wounded Knee.

I would have a demand and questions that I would like to adress to you in a more personal and confidentiel way of it’s possible.

May we talk by email please ? I don’t find anything here where I could write to you

Thanks anyway for your work and your attention

Vivianne

LikeLike

Fascinating research and post! While preparing to teach about the Chicago World Fair to my anthropology students, I came across several details of Emma Sickels’ involvements in it. If you don’t know it already, I think you would be interested in Nancy Egan’s article entitled “Exhibiting Indigenous Peoples: Bolivians and the Chicago Fair of 1893.” Studies in Latin American Popular Culture, Vol. 28, 2010

LikeLiked by 1 person