This photograph can be viewed in greater detail at “Military Mystery: U.S. Cavalry 9th Regiment Company G?” Where Honor Is Due: Our Men of Military Service.

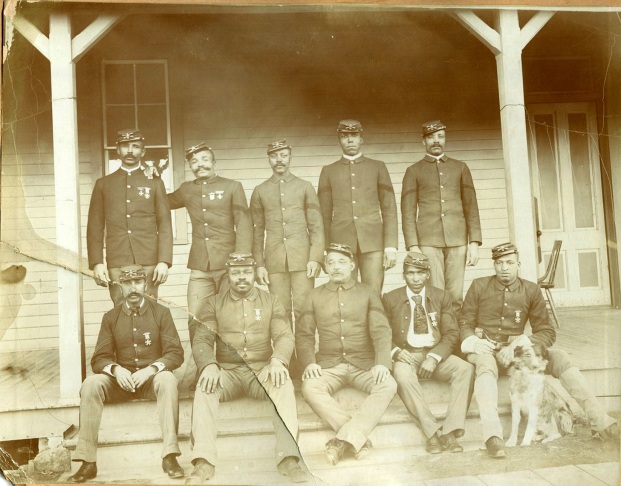

Occasionally, a historical photograph surfaces from an old trunk in an attic that piques the interest of historians and enthusiasts alike. Such was the case this month when a picture of ten non-commissioned officers of Troop G, 9th Cavalry, came to light and was published in the Taos News under the title, “Mystery of the ‘Buffalo Soldiers’ photo.” According to the article, Taos resident Gloria Longval wishing to honor Black History Month brought the photograph to the attention of the local news outlet. Mrs. Longval intimated that she came into possession of the photograph entirely by accident about fifty years ago. After buying several frames at an auction, she discovered the photograph under an illustration in one of the frames.

A historian and blogger by the name of Luckie Daniels has taken up the cause to identify the men in the photograph. One of her readers, William F. Haenn, a retired army lieutenant colonel and published author opined:

The medal five of the soldiers are wearing shows they are members of the Society of the Army and Navy Union of the United States. Badges of Military Societies were first authorized for wear in the 1897 Army Uniform Regulations. Typically uniform regulations served to catch up with what was already a common practice. Safe to say the photo is early to mid-1890s. The other badges are marksmanship badges.

The two soldiers in the upper left are wearing sharpshooter badges (maltese cross) and the soldier second from the left is [also] wearing a distinguished marksman badge [pictured at right]. The solider with a cravat bottom row second from the right is wearing a marksman silver bar. All the soldiers are non-commissioned officers, six sergeants and four corporals.

The leggings worn by the soldier in the front row far right were not adopted for wear by cavalrymen until 1894. Leggings replaced the traditional cavalry boots in that year. The photo had to be taken after 1894.

The 9th Cavalry Regiment was stationed at Fort Robinson, Nebraska throughout the 1890s until deployed to Cuba in the War with Spain in 1898.

Based on Haenn’s assessment, the photograph most certainly dates from the mid-1890s at Fort Robinson, Nebraska. These same cavalrymen very likely participated in the Pine Ridge Campaign of 1890-1891. Named for their commander, Major and brevet Colonel Guy V. Henry–perhaps the most renowned Indian fighter in uniform at the time–the 9th Cavalry during that campaign were dubbed “Henry’s Brunettes.”

A 26 January 1891 article in the Omaha Bee, detailed Major General Nelson A. Miles’ review of all the soldiers gathered in Pine Ridge at the end of the campaign. The article mentions Troop G as being under the command of Lieutenant Grote Hutcheson, who later served as the regiment’s adjutant and wrote the first history of the 9th Cavalry for the book, “The Army of the United States, Historical Sketches of the Staff and Line.” Bee correspondent Ed O’Brien wrote:

Then came the Ninth, the fame of which in this campaign is the subject of general conversation. In a certain sense it was the leading feature of the parade. The troopers are colored. They wore buffalo overcoats. Long or short, light or heavy, they sat there on horses like Neys. They seemed to glory in the soldier’s life, to take to it as kindly as do the savages to the warpath. They looked like Esquimaux rigged out for an active campaign and demeaned themselves as if they were alike fearless of the elements and storms of shot and shell. At their head rode Colonel Henry, the fearless man who has led them in their rides over these hills and valleys and both into and out of the mouth of hell, which they have experienced on several occasions. Lieutenant W. Finley acted as adjutant, Dr. Kane as medical officer and Lieutenant Bettens as quartermaster.

The First battalion was commanded by Captain Loud, A troop by Captain Garrard, I troop by Lieutenant Perry, G troop by Lieutenant Grote Hutcheson, in the absence of the veteran Captain Cusack, who was seriously ill. The guidon of this troop was badly punctured with bullets.

The Second Battalion was commanded by Captain Stedman, K troop being led by “Light-Horse Harry,” Captain Wright, the young gentleman who has just received the spurs of his present rank which even was celebrated on the field of battle. F troop was led by Lieutenant McAnany and D troop by Lieutenant Powell. A Hotchkiss battery brought up the rear.

A more famous narrative of General Miles’ review written by Charles Seymour appeared in Harper’s Weekly:

…..And when the black scowling faces of the Ninth Cavalry passed in close lines behind the glittering carbines held at a salute, General Miles waved his gloved hand to Colonel Henry, whose gaunt figure was almost lost in the folds of his buffalo overcoat. Three weeks before, these black troopers rode 100 miles without food or sleep to save the Seventh cavalrymen, who were slowly being crushed by the Sioux in the valley at the Catholic Mission. Then they dashed through the flanks of the savages, and after sweeping the ridges with carbine and pistol, lifted the white troopers out of the pocket with such grace that after the battle was over the men of both regiments hugged one another on the field.

Henry later wrote a detailed account of the 9th Cavalry’s actions during the campaign including the famous 100-mile ride that culminated with the rescue of the 7th Cavalry at the Drexel Mission fight on White Clay Creek, 30 December 1890. Following is Henry’s narrative printed in the 4 January 1897 edition of the Omaha Daily Bee.

Henry later wrote a detailed account of the 9th Cavalry’s actions during the campaign including the famous 100-mile ride that culminated with the rescue of the 7th Cavalry at the Drexel Mission fight on White Clay Creek, 30 December 1890. Following is Henry’s narrative printed in the 4 January 1897 edition of the Omaha Daily Bee.

A SIOUX INDIAN EPISODE.

RECOLLECTIONS OF THE PINE RIDGE WAR.

(General Guy V. Henry in Harper’s Weekly.)

While seated in my office at Fort McKinney, Wyo., on the 19th day of November, 1890, the following telegram was handed to me:

“Move out as soon as possible with the troop of cavalry at your post; bring all the wagon transportation you can spare, pack mules and saddles; extra ammunition and rations will be provided when you reach the railroad.—By Order of the Department Commander”

What possible cause for this interruption of our peace and happiness and the breaking up of our homes, settled for the long and usually trying winter, and the leaving of our families could not be imagined. A distance of nearly 200 miles from the railroad, uncertain mail and telegraphic facilities, or at least much delayed news, kept us ignorant of outside troubles.

Preparations were at once made, and the following day I marched out of Fort McKinney with troop D, Ninth cavalry, Captain Loud, Lieutenants Powell and Benton. Turning the point of a hill, after crossing the beautiful Clear fork of the Powder river, the post and our families were soon lost to sight. Little did we suspect at the time that we were never to return to Fort McKinney as a station. This is a peculiarity of army life—to leave on twenty-four hours’ notice a place, possibly never to be seen again, or maybe only when, after a lapse of years a similar notice may as suddenly return you to your old station. Nearing the railroad, we began to hear all sorts of rumors of the Indians being on the warpath—the murder of settlers, the starting of a party of Indians in the direction of Fort McKinney so as to obtain a refuge in the Big Horn mountains; these and other reports found us mentally prepared for a winter’s campaign, so that on reaching the railroad we were not surprised to find cars in readiness to carry us to Rushville, the nearest point to the reported place of trouble—Pine Ridge agency, South Dakota.

We arrived at Rushville at night, and immediately detrained, and started early the following morning on our march to the agency, where we arrived early in the afternoon of the same day. Contrary to expectations we met with no hostile Indians or resistance.

We found all the troops camped close about the agency, and made our own camp in the bottom, about half a mile away, on White river. The next day we were joined by troops K, F and I, with Captains Wright and Stedman, and Lieutenants Guilfoyle, McAnaney and Perry, Dr. Keane being the medical officer; the four troops constituted the Ninth cavalry squadron. Our time was fully occupied in daily drills and in getting our pack-mule train in order, for upon this we depended for rations and forage when absent from our wagons. Rumors came often to us that the Indians were keeping up their ghost-shirt, or Messiah dances; that they considered these shirts, when worn, to be impervious to the bullet; of their desire to clean out the whites and to occupy the promised land; of their having occupied an impregnable position in the Bad Lands, so fortified and difficult of approach that an attempt to dislodge them would result in the annihilation of the whole army—these and many other rumors gave the Indian, who is a great braggart, an abundant opportunity to air himself, and left us plenty of leisure to prepare ourselves for our future state.

The afternoon of December 24 an order reached us to move out at once to head off Big Foot—an Indian chief—and his band, who had escaped from our troops, and, it was supposed, would join the hostiles in the Bad Lands; and this we were to prevent. So at 2 p.m. the “general” sounded—a signal which meant to strike our tents and pack our mules and wagons. The latter were to follow us, escorted by one troop. Soon “boots and saddles” rang out, when horses were saddled, line formed, and then, with three troops and with two Hotchkiss guns of the First artillery, under Lieutenant Hayden, we commenced our march of fifty miles, expecting to reach our goal before daylight. Only a half-hundred miles! It does not seem far on paper, but on the back of a trotting horse on a cold winter’s night it is not to be laughed at. On we dashed through the agency, buoyed by the hearty cheers and “A Merry Christmas!” given us by the comrades we were leaving behind to revel by the camp-fires, while we rode on by moonlight to meet the foe. Every heart went out in sympathy with us, every one waved his hat and cheered as we rode out on the plains—perhaps to glory, perchance to death. Proud and gallant the troopers looked, more as if going on parade than like men riding forth, it might be, to meet a soldier’s death. It made one’s heart beat quicker, and brought to mind the words:

To sound of trumpet and heart-beat

The squadron marches by;

There is color in their cheeks,

There is courage in their eyes;

Yet to the sound of trumpet and heart-beat

In a moment they may die.Little did we think at that time that within less than one week some of the gallant men we were leaving behind would be killed by the very band we sought, while we should be saved. After riding for two hours, alternately at a trot and a walk, a short halt was made for the men to make coffee and to give the horses a feed. Then the march was continued, and on and on we sped, that cold, moonlit Christmas eve. The words, “Peace on earth, good will toward men,” rang in our ears as we pushed on with hostile intent toward the red men. The night was beautiful with the clear moon, but so cold that water froze solid in our canteens, notwithstanding the constant shaking. Crossing a narrow bridge, a pack-mule was shoved off by its crowded comrades, and, falling on the ice of Wounded Knee creek, broke a hole, smashed a box of hardtack, but gathered himself together and ambled off, smiling serenely at having received no damage to his body.

Here we passed abandoned ranches, the owners driven off by threats or fear of the Indians; here we were at the scene of the ghost dance, where the Indians were taught that the Messiah would appear, rid the country of the white man, and bring plenty to the Indian; that the common cotton ghost shirt worn was bullet proof; while in every other possible way the medicine-men worked upon the fanaticism of the deluded creature. We saw at a distance stray cattle, whose spectral appearance almost led us to believe in ghosts, if not in ghost shirts, and an examination was made to see whether or not they were Indians waiting on their ponies to attack us.

To cross White river we had to take a plunge from solid ice to mid-channel water, and then rode to Cottonwood springs, at the base of the position of the Indians in the Bad Lands. We reached this place at 4 a.m., and threw ourselves on the ground for rest, knowing that to obtain wood and water for breakfast Christmas morning we should have to march eight miles. And this is the way the Ninth cavalry squadron spent Christmas eve of 1890. Christmas day we proceeded to Harney springs, a place where I had encamped during my winter’s march on seventeen years before, and finding wood and water, we made our breakfast. We scouted the country for several days to find Big Foot’s trail, but he had passed east of us. We discovered the tepees of the Indians, but finding no trace of the former occupants, we returned to White river. The next day we made a reconnaissance of the Bad Lands. Instead of narrow trails or defiles of approach accessible only in single file, where we could have been shot down by the Indians at will, we found a broad open divide; instead of impregnable earthworks, only a ridiculously weak pile of earth existed, here and there, filled in by a dead horse. The Indians occupied a narrow position, from which they could easily have been shelled. They had taken one military precaution, however, that of preparing for retreat, and had cut openings in the bluffs, which on their side were abrupt, so that they could slide down and escape. The reality, as compared with the reports of Indian guides and interpreters, was greatly exaggerated, all brag and bluster, and but for the existence of high hills, little more than a “bluff” on the part of the Indians. I had spent many a moment, when I supposed we should have to make an assault on this position, thinking how it could be done, and worrying over the probable loss of life, such perhaps as had occurred in the Lava beds when troops were opposed to the Modoc Indians; but when I saw this burlesque I could only laugh, and I made up my mind that it was best not to cross Fox river till it was reached.

It was not 10 o’clock at night, the wind was cold, and as it howled out of the canyons and swept over the valley, it carried with it the crystals that had fallen the day before. There was no moon, the night was inky dark, even the patches of snow which lay here and there on the ground gave no relief to the eye. Muffled in their shaggy buffalo overcoats, and hooded by the grotesque fur caps used by our western troops, the negro troopers looked like meaningless bundles that had been tied in some way to the backs of their horses. Through canyons whose black walls seemed to be compressing all the darkness of the night, over buttes whose crests were crowned with snow, and across the rickety bridges which span Wounded Knee and Porcupine creeks the command sped at a pace which would have killed horses that had not been hardened by practice, as ours had been. Nothing could be heard but the clatter of hoofs and the clanking of the carbines as they chafed the metallic trappings of the saddle; silence had been ordered, and the usual laugh and melodious songs of the darky troopers were not ours to beguile the march. Now and then came the reverberation of the mule-whacker’s whip as he threw his energy and muscle into a desperate effort to keep the wagon train near us; figures could be seen flitting across the road and on the bluffs, and we knew not at what moment we might be fired upon; accordingly, the effort was made to reach the agency before daybreak, in the hope that darkness and the Indians’ superstition would protect us from attack in the meantime.

As we neared the agency the country became more open, hills easy of occupation commanding the road if the occasion required. So, in order to enable us to get our horses into camp, and the riders and saddles off our weary animals, we left the wagon train a short distance in the rear, guarded by one troop, and the column moved on, entering the agency at daybreak, men and horses much tired after our long day and night ride of about 100 miles. Reaching our old camp we all sought rest at once by throwing ourselves on the ground, but we had been resting only a short time when Corporal Wilson of the wagon train guard, who had volunteered at the risk of his life to reach us, rode rapidly into camp and reported that the train beyond the agency was surrounded and one man already killed. In a moment the command, many not waiting to saddle, galloped to the front and quickly occupied the hills, whereupon the Indians retreated and the train moved in.

Scarcely had we returned to camp when orders were received to proceed to the Mission, the smoke from whose buildings indicated Indian depredations. By request, owing to tired men and horses, we were allowed to rest longer, the Seventh cavalry going out. Later we went to the Mission as rapidly as our wearied horses could carry us, and, after accomplishing the purpose for which we had been urgently called, returned, reaching our camp about dusk. We had marched some 103 miles in twenty-two hours, and, although one horse had died, there was not a sore-backs horse in the outfit; men and horses were fatigued, but all were in good condition. The following day, December 31, we remained in camp, with a howling snow storm prevailing, and amid these gloomy surroundings the Seventh cavalry buried its dead. January 1, again under orders, we left the agency to combine with other troops in forming a cordon to drive back the hostiles who had fled from the agency, or to follow them if depredations upon the settlements were commenced. Finally the Indians were forced back to the agency, not, however, until Lieutenant Casey had been killed by them, nor before they saw that resistance was useless, and that the ghost shirt was not impervious to the bullet.

Preparations were then made for a final review of troops. We were encamped in line of battle, extending nearly three miles, which made a great impression upon the Indians, many of whom looked on from a distance in amazement and distrust, fearing that our arrangements might mean an attack instead of a peaceful march in review previous to the return of the troops to their posts.

The morning broke with a pelting flurry of a combination of snow and dirt. A veil of dark clouds hung suspended above the hills, which surrounded the camp ground like a coliseum, and a piercing breeze swept from the north, making the contrast with the previous Messiah weather we had been having anything but agreeable. We were fearful that a Dakota blizzard might strike us, meaning death to our animals in their exposed position and probably serious results to the soldiers. Accordingly we all were anxious that the review ordered by General Miles be not postponed.

General Miles, after passing along the line, took position opposite the center, so that the troops, all of whom had participated in or rendered service during the Pine Ridge troubles, might march past him. They moved in column of companies, troops, or platoons, and by infantry, cavalry, and artillery corps, respectively, and in order as above. General Brooke and staff headed the column, followed by the band of the First United States infantry. When opposite General Miles the band wheeled out of the column, playing, or attempting to do so, during the passage of the troops—a difficult matter, as the fierce wind almost prevented any musical notes being made or heard.

Then came 100 mounted Ogallala Indian scouts, commanded by Lieutenant Taylor of the Ninth cavalry. Their precision of march was noticeable, and in various ways they had rendered valuable service during the campaign. General Wheaton, as a brigade commander, followed with his staff. The first regiment of his command was the First United States infantry, under Colonel Shafter, whose martial appearance and indifference to the cold—the men not wearing overcoats—suggested blood warmed by their California station. Then came the Second United States infantry under Major Butler. Their marching showed service, and they had recently lost Captain Mills, whose sad death in his tent as reveille sounded was fresh in the minds of his comrades. Next followed six companies of the Seventeenth infantry, under Captain Van Horne, who marched well; then two companies of the Eighth infantry with a Gatling gun, under Captain Whitney; then Captain Capron with his light battery of the First United States artillery, which had distinguished itself at the battle of Wounded Knee creek during the fight with Big Foot’s band on December 29, and afterward at the Mission. Next in order came General Carr, commanding the cavalry brigade, followed by the historic and veteran Sixth cavalry and the Fort Leavenworth cavalry squadron, composed of one troop from each of the First, Fifth and Eighth regiments of cavalry, followed by a Hotchkiss battery; then came the scowling black faces of the Ninth cavalry squadron, with three other troops, A, C and G of the same regiment, who passed at “advance carbine” and whose gallant and hard service is of official record; then the Seventh United States cavalry, whose fine appearance attracted attention, and whose losses in action were attested by the vacancies in the ranks made by the gallant men killed or wounded. The ambulance wagon and pack-mule trains brought up the rear, making a total in passing of about 3,600 men and 3,700 animals.

The column was pathetically grand, with its bullet-pierced gun carriages, its tattered guidons and its long array of cavalry, artillery and infantry, facing a pitiless storm which caused the curious Indians who witnessed it to seek protection under every cover and butte which could be found. It was the grandest demonstration that had ever been seen by the army in the west, and when the soldiers had gone to their tents the sullen and suspicious Brules could be seen going to their tepees in ill-disguised bad humor. The forces disbanded in a few days, the First infantry remaining at the agency for one month, while the Ninth cavalry squadron was ordered to select a comfortable winter camp, and to remain till spring.

Our comfortable camp was located on a small stream under cover of a high bluff, which, like a snow fence, secured and held the drifting snow from the plain above and caused a bank of snow twenty feet high and ten thick to form beyond and near our camp. The men had stoves in their tents, but their beds were on the ground; the officers were a little better off. The animals had canvas blanket covers. But with all this there was suffering in various ways. There were damp, cold nights; many had colds and pneumonia; there were few comforts. But yet our soldiers did not complain. On the contrary, it would have been difficult to find a more truly happy lot than those colored troopers.

Each of the big Sibley tents held fifteen or sixteen men, and when supper was over (bread and coffee, and sometimes a little bacon), these little communities settled down to have a good time. Song and story, with an occasional jig or a selection on the mouth-organ or the banjo, with the hearty laugh of the darky, occupied the night hours till “taps” sounded for bed; and the reveille, or awakening, seemed to find these jolly fellows still laughing. The Indians seem to hold the darky in reverence, if not awe. The doctrine of the Messiah religion is that all the whites are to be cleaned off the earth—and this leaves the negro. The Indians have a superstition that the bullet cannot kill the darky; but this, as with the ghost-shirt “not-kill” theory, had been dispelled by actual experience.

The negro is not easy to scalp—I have never heard of one being scalped, their wool not giving so good a hold as the hair of the white man—and the theory is that only those who are scalped are kept from the “happy hunting grounds,” where the fighting unfinished on earth is continued. It is certain that the treatment of the black by the Indian is different from that given to the white, and when thrown together the red man seems to hold the black in greater respect. I recall an instance in my youth when a band of Indians attacked a party of whites, killing the men and children, but keeping a white woman were obliged to change clothes, showing the greater respect for the black, who was treated then and afterward with consideration, while the white woman was killed when on the eve of recapture by our troops who had pursued the Indians.

The colored troops make excellent soldiers; in garrison they are clean and self-respecting, and proud of their uniform; in the field patient and cheerful under hardships or deprivations, never growling nor discontented, doing what is required of them without a murmur. Arriving in camp after hours in the rain or cold they will sing and be happy; an enforced reduction of rations is received with good humor. The peculiar owl-like character of the negro, who apparently does not need so much sleep at night as the white man, makes him a good and vigilant sentinel.

If properly led he will fight well; otherwise, owing to his habit of dependence upon a superior, he is more liable to stampede than the Caucasian; nor has he, as with the white, except in exceptional cases, the same individuality or self-dependence—he goes rather in a crowd and you seldom see a negro by himself. He is generous to a fault and has but little regard for the care of the United States property, for which neglect he pays, but in this respect he is much improved over former years. He is like a child, and has to be looked after by his officers, but will repay such interest by a devoted following and implicit obedience. It would not be safe to suggest to some of these black troopers your desire that one of their comrades, whose conduct had not met with approval, should be hung before daylight, for it would very likely be an accomplished fact. Drunkenness is not one of his vices—it is seldom you see one under the influence of liquor; his loyalty to the flag is unquestioned, and the desertion of one is almost unknown.

The above are some of the virtues of the black trooper, all necessary attributes of a good soldier. Card playing—and he is an inveterate gambler, as is also the Indian—is one of his vices, if such it may be called. His defective education leads him to indulge in it largely as a means of whiling away the time.

Our service with such men made the disagreeable camp surroundings endurable, even pleasant, and imparted to the white officers a more contented feeling, or at least an acceptance of the situation in a more equable manner than would otherwise have been the case.

Spring came, and with it our orders to march to Fort Robinson, a station where I had been seventeen years before, when on my winter’s march to the Black Hills. I was now to return to it under very different circumstances. Leaving our winter camp, and marching through deep snows, we made the town of Chadron, on the railroad, the first day, our men sleeping in a building loaned by the citizens. The second day we marched nearly forty miles through deeper snows up to the girths of the saddles, in drifts much deeper, and, as the snow began to melt, through lakes of slush and bog, many of the men and animals becoming snow blind. As the retreat gun fired, with the band playing a welcome, we entered Fort Robinson, thus ending the duties of the Ninth cavalry squadron in the Pine Ridge Sioux Indian campaign.

For further reading on the amazing military career of General Guy Vernon Henry, Sr., I recommend Cyrus Townsend Brady’s, “What They Are There For” in the October 1903 edition of Scribner’s Magazine.

Sources:

Daniels, Luckie, “Military Mystery: U.S. Cavalry 9th Regiment Company G?” Where Honor Is Due: Our Men of Military Service (https://wherehonorisdue.wordpress.com/2015/02/16/military-mystery-u-s-cavalry-9th-regiment-company-g/), posted 16 Feb 2015, accessed 28 Feb 2015.

Haenn, William F., from comments posted on “Are Our Soldiers Wearing GAR Medals? #BuffaloSoldier,” Where Honor Is Due: Our Men of Military Service (https://wherehonorisdue.wordpress.com/2015/02/20/are-our-soldiers-wearing-gar-medals-buffalosoldier/) posted 20 Feb 2015, comments 26 and 27 Feb 2015, accessed 28 Feb 2015.

Henry, Guy V., “A Sioux Indian Episode,” Omaha Daily Bee (4 Jan 1891), 7.

Hutcheson, Grote, “The Ninth Regiment of Cavalry,” The Army of the United States Historical Sketches of the Staff and Line With Portraits of Generals-In-Chief by William L. Haskin (New York: Maynard, Merrill, & Co., 1896), 280 – 287.

O’Brien, Edward A., “The March of Forces,” Omaha DailyBee (26 Jan 1891), 2.

Romancito, Rick, “Mystery of the ‘Buffalo Soldiers’ photo,” The Taos News (http://www.taosnews.com/entertainment/article_2891a05a-b9d8-11e4-b7f2-4b042719192c.html), posted 21 Feb 2015, accessed 28 Feb 2015.

Seymour, Charles G., “The Sioux Rebellion, The Final Review,” Harper’s Weekly, vol. 35

(7 Feb 1891), 106.

Citation for this article: Samuel L. Russell, “Henry’s Brunettes,” Army at Wounded Knee (Sumter, SC: Russell Martial Research, 2013-2015, http://wp.me/p3NoJy-Jg), posted 28 Feb 2015, accessed date __________.

I found this narrative about the Wounded Knee campaign very moving, very real, almost romantic. Tough soldiers all. My Army relative Louis Nuttman, eventually a Major General, served in Cuba, China WW1 different wars altogether.

Regards

Susan

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: 9th & 10th Cavalry: Setting Our Sight on Fort Robinson | Where Honor Is Due: Our Men of Military Service

I really enjoyed reading this entry. I have been all over the reservation and been to many of the places mentioned. The winters there really are rough and can be brutal. I don’t think Chadron and certainly Rushville have changed too much since those days. This is one of my favorite periods in history. It is very interesting to me to compare the Army version with the version I get from my Oglala friends.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very surprised to find a picture of my distinguished marksman’s badge posted here as I had given it to a friend to post on the Militaria forum. This is a perfect place for it but wondered how it got here shadow and all. If I had known it would circle the net I would have taken a better photograph.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tom… Thank you for reaching out. I would like to properly cite your photograph of your distinguished marksman’s badge. Can you provide me some detail of the photo, viz., date and place, and any other brief detail regarding the badge?

Warmest regards, Sam Russell

LikeLike

The medal is one of the first fifty made by New York jeweler Jens Pederson. It is not engraved with the name of the awardee as this was left to the trooper or his unit to have done.I have had the badge for some years now and sent the picture to Don Harpold another collector of frontier army marksmanship awards to be included in a post of his on a Militaria web site. It is top center in the photograph.

LikeLiked by 1 person