Immediately after the volley, from 100 to 150 Indians rode up on three sides and opened fire on us. We fell back about 400 yards to a good position and stood them off.

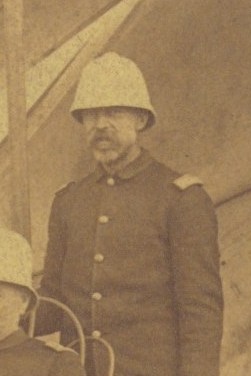

At fifty-three years of age, Captain Henry Jackson, was one of the most experienced company commanders in the 7th Cavalry at Wounded Knee. He had been the commander of C Troop for over fourteen years since being promoted to fill the vacancy created by Captain Thomas Custer’s death at the Little Big Horn. Jackson had been on active duty almost continually since December 1863 and claimed to have served as an officer in the British army in the 1850s.

C Troop was one of four company sized elements of the regiment’s 2nd Battalion, which during the Pine Ridge Campaign was commanded by the senior captain in the regiment, Charles S. Ilsley. As a part of the 2nd Battalion, Captain Jackson and his C Troop arrived at Wounded Knee with Colonel Forsyth on the night of 28 December, after the Lakota had set up their village on the south side of Major Whitside’s camp. Captain Ilsley filled the battalion commander role because Colonel Forsyth had only one of his field grade officers, Major Whitside, present during the campaign, the others being stationed at Fort Sill or on detached service in other capacities. As one of the senior captains in the regiment, Colonel Forsyth used Captain Jackson in the old cavalry role of a squadron commander, that is, he was in charge of two troops, C and D, that were tactically dispersed from their battalion commander. Captain Ilsley’s other two troops, E and G, were positioned on the north side of the ravine with Ilsley positioning himself at the council circle near Forsyth and Whitside. Jackson was in charge of his C Troop and Captain E. S. Godfrey’s D Troop on the south side of the ravine. Interestingly, Jackson makes no mention of being in charge of Lieutenant Taylor’s Indian Scouts that were also positioned in that proximity.

As with all ten line companies at Wounded Knee–eight troops from the 7th Cavalry, one battery from the 1st Artillery, and one troop of Indian Scouts–Captain Jackson had only one of his two officers present. First Lieutenant Luther R. Hare deployed with the regiment to Pine Ridge, but returned to Fort Riley on 15 December suffering from muscular rheumatism, a common ailment among cavalry officers that spent a lifetime in the saddle. Jackson’s Second Lieutenant, Thomas Q. Donaldson, was present and on duty with C Troop at Wounded Knee. The senior non-commissioned officer of C Troop that morning was First Sergeant John B. Turney, a thirty-four year old seasoned soldier with eight years experience with his troop and regiment. A review of the C Troop muster roll for the month of December 1890 indicates that Jackson had five sergeants, two of four corporals, his farrier, blacksmith, saddler, and wagoner, and as many as forty-two privates at Wounded Knee, nine of whom were new recruits that joined the regiment at Pine Ridge just weeks before the battle. The new recruits did not increase Jackson’s available strength however, as he had discharged seven soldiers in the weeks preceding the battle and had several absent either on furlough, sick in hospitals, or in confinement.[2] Concerning the fighting strength of the unit on the campaign in December, First Sergeant Turney detailed the following in a letter to his wife back at Junction City, Kansas.

We received 10 new men from the 62 assigned to the Regiment. They came from [Fort] Robinson some days ago, and they had a rather rough induction to soldier’s life joining the troops in the field on an Indian campaign. “C” Troop started away with 45 men present and it now has 56 present which is the full allowance for a cavalry troop now.[3]

Captain Jackson detailed his role at Wounded Knee when he was called to testify on 9 January 1891 at Major General Miles’s investigation into Colonel Forsyth’s management of the Wounded Knee affair. After being sworn in by the board, Jackson responded to a series of questions from Major Kent and Captain Baldwin beginning with, “Did you command C Troop during the engagement on the Wounded Knee on the 29th of December, 1890?”

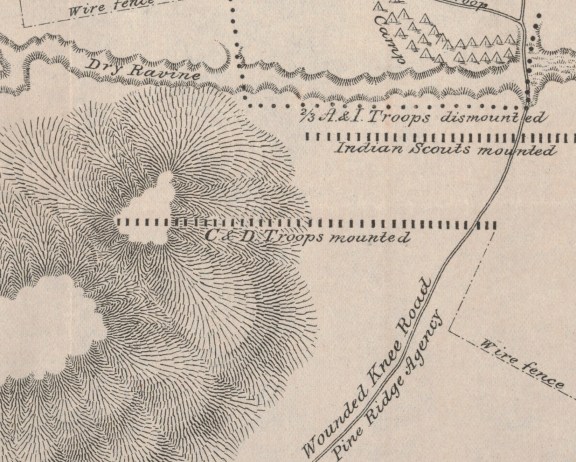

I commanded C and D Troops, located as shown on the map (referred to), but C Troop extended more to the right and not so far to the left, and D Troop was on my left.[4]

(Click to enlarge) Inset of Lieut. S. A. Cloman’s map of Wounded Knee depicting the position of C and D Troops, December 29, 1890.

The board’s next question regarded friendly fire. “Did these Troops, in the position indicated, receive the fire from other Troops?”

I could not tell; we received a heavy fire, coming from the northwest; one man was injured in this fire. I did not fire in the direction of any other of our Troops.[5]

Kent and Baldwin next inquired about the killing of noncombatants. “What precautions did you take, in the pursuit of the Indians, to prevent unnecessary killing of Indian women and Children?”

The only women I noticed was in the break out of the Indians. I saw a party of 8 or 9 women and children, who kept bunched together; I saw they were women because they had their children with them; and, right there, cautioned the men not to fire on them; a party of my Troop conducted them to a place of safety.[6]

The board followed up with, “What people were killed in rear of your first position?” To which Jackson provided a lengthy response that detailed a shift in the fight from the ravine to pursuit of the surviving Miniconjou to prevent their escape.

I saw several bodies lying on the ground, and I know that two of them were bucks at least. While the firing was going on, Major Whitside rode up to me and gave me an order, pointing to a herd of ponies some 2 miles in a northwesterly direction, and told me to take my Troop up to the Hills and to round up anything I found there and to bring in those ponies. I started due west, up the bluffs, and had to travel over 2 miles to the head of the ravine. Just as we headed it, at the point where the road came in, as we were turning at the head of the ravine, I saw an Indian slide down the bank into it; I had 34 men with me of C Troop. I dismounted them to fight on foot and surrounded the head of the ravine; after we closed up on it, the firing began both from my men and some Indians, and we fought there, gradually closing in, and I sent Lieut. Donaldson and some men to cut off their retreat down the ravine. The Indians were in a hole under the bank, and we could only see the points of their guns, and I thought, from the looks of the place, that it held only one or two Indians. In the fight one of my men was killed. Lieut. Taylor, with two Indian scouts, came up about that time, and I thought I heard children crying, and I told Lieut. Taylor to send one of his scouts to say that if the squaws came out they would not be harmed. It took half an hour’s talking with them, and I had to withdraw my men before they would come out. We got 19 women and children there. There was one woman badly hurt and one or two others had been hit. We got 5 bucks at the same time, 4 badly wounded, and one shot through the ankle; we dressed the wounds of all as far as the dressings reached. I sent word in to General Forsyth that I had them and asked for a wagon to bring them in. While waiting, six Indians rode down to me from the direction of the agency and shook hands with me, also Captain Godfrey and Lieut. Donaldson. Godfrey had joined a while before with 14 men. One of the Indians wore a policeman’s shield. They said “How,” turned round and rode their ponies back up this road. They went off 75 or 100 yards, turned round, and fired a volley at me. One of the six, I think it was the one that wore the Indian policeman’s shield, waved his hand as though in efforts to stop the rest. Immediately after the volley, from 100 to 150 Indians rode up on three sides and opened fire on us. We fell back about 400 yards to a good position and stood them off. They saw G Troop coming up on the jump, and they, the Indians, did not follow us. Captain Ilsley came up and ordered me back to camp. I had been obliged to abandon my prisoners when first I was jumped. I had sent word to General Forsyth that the attacking party were Agency Indians, about 150 of them. General Forsyth sent the two Troops E and G.[7]

Kent and Baldwin asked a final question, “Under the circumstances attached to the work of that day, do you consider that the disposition of the troops, just before the fight opened, was a judicious one?” Jackson’s response hinted that perhaps Colonel Forsyth and Major Whitside could have better positioned the troops before the onset of hostilities.

I think if it had been myself, I should have left one flank open, but I don’t think any one supposed that there would be fighting; I certainly did not.[8]

Between the fights on 29 and 30 December, Captain Jackson’s C Troop suffered a seven percent casualty rate with one trooper killed and two wounded at Wounded Knee, and one wounded at White Clay Creek. This was the highest casualty rate suffered among the four troops in Captain Ilsley’s 2nd Battalion, but less than half that of any of the four troops in Major Whitside’s 1st Battalion.

Of all the officers in the 7th Cavalry Henry Jackson’s origins are the least known. That he was born in England is well established, likely in Canterbury, but the commonality of his name makes finding his place and date of birth difficult. A review of his U.S. Army records fails to identify the names of his parents or any relatives other than his wife. Jackson provided scant detail of his early life in a letter requesting a commission following the Civil War.

![Lieutenant Henry Jackson's letter requesting a commission upon in activation of the 5th U.S. Colored Cavalry.[x]](https://armyatwoundedknee.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/henry-jackson-commission-application.jpg?w=212&h=300)

Lieutenant Henry Jackson’s letter requesting a commission upon in activation of the 5th U.S. Colored Cavalry.

Headquarters fifth U. S. Colored Cavalry

Helena, Ark., 15 January 1866.Adjutant General

U. S. Army, Washington D. C.

General,

I have the honor to apply for a Lieutenancy in the permanent Army of the United States. I entered the service in December 1863 in the 14th Illinois Vol. Cavalry and served with them till January 1865 when I was transferred to the 5th U. S. Col. Cav. and appointed Serg’t Major. In May 1865 I was commissioned as 2nd Lt. and was appointed Regimental Adjutant and in December 1865 I was commissioned 1st Lieutenant. I have served two years in the English service as Ensign and Lieutenant. I am 31 years of age and enlisted at Peoria, Ill.

I have the honor to be General

Very respectfully Your obdt. Servant

[signed] Henry Jackson Lt. & Adj. 5 U.S.C.C.[9]

Jackson’s statement that his age was thirty-one in 1866 put his year of birth in 1835. He reaffirmed his birth year in a statement to a commissioning board, but in later years established his date of birth as 31 May 1837. Establishing an officer’s actual date of birth was important to the Army as it determined when the officer reached mandatory retirement at sixty-four. As with many young men throughout the history of military conflict, he likely lied about his age when a teenager, enabling him to enter the British Army and possibly participate in the early campaigns of the Crimean War in 1853 when he was but sixteen. Jackson’s statement to the commissioning board established that he had immigrated to America by 1860. Additionally, he provided greater detail of his service in the Union Army during the war of the rebellion listing the battles in which he participated while campaigning in Tennessee, North Carolina, and Georgia.

My name is Henry Jackson – I was born in England in the year 1835. I have resided in the State of Illinois from the year 1860. I entered the Military Service of the U. S. in December 1863 in the 14th Illinois Vol. Cav. I served with the 14th Ill. Cav. at Mossy Creek, Tenn., French Broad River, N.C. Feb. 64., Ellijay, Big Shanty, Kennesaw Mountain, the fights on the Chattahoochee from 26th June to 6th July, 1864. Then on Gen. Stoneman’s Raid to Macon including the fight at New Hope and Lawrenceville. We then returned to Kentucky when I was transferred to the 5th U.S. C. Cav. as Sergt. Major; in May 1865 I was commissioned as 2nd Lt and was appointed Regimental Adjutant and in December 1865 I was appointed 1st Lt. and served as such until March 1866 when I was mustered out of the U.S. Service. I was mustered into the U.S. Service at Camp Butler, Ills. about the 25th Jan. 1864.

[signed] Henry Jackson[10]

Jackson was commissioned a Second Lieutenant with the newly formed 7th Cavalry Regiment in July 1866, and accepted the appointment the following November. By July the following year he was promoted to First Lieutenant. Early in 1868 Lieutenant Jackson was assigned to special duty on Major General Philip Sheridan’s staff as an engineer for the Department of the Missouri. This duty and a subsequent one with Office of the Signal Officer in Washington kept him away from his regiment for over eight years. As such he missed much of the 7th Cavalry’s active campaigning in its early history, including the battle along the Washita River, the Black Hills Expedition of 1874, and the summer of the Little Big Horn campaign of 1876 and 1877. Upon promotion to captain following the death of Thomas Custer at the Little Big Horn, Jackson rejoined his regiment in November of that year passing through Fort Abraham Lincoln, Dakota Territory, long enough to receive orders to Fort Totten where he took command of C Company. Jackson was on detached service in Deadwood the following August and September when much of the 7th Cavalry was engaged in battles at either Canyon Creek or Bear Paw Mountain during the Nez Perce Campaign, making Jackson one of the few, if not the only, original member of that storied regiment that did not participate in any of the major campaigns during its first tumultuous decade.[11]

While stationed at Fort Leavenworth in 1870, Jackson married Miss Elizabeth Calhoun, the thirty-two-year-old daughter of John and Sarah (Cutter) Calhoun. John Calhoun was a wealthy surveyor and lawyer from Springfield, Illinois, where he had been friends with Abraham Lincoln and active in state politics. He did not live to see his friend become president, dying in 1859 shortly after relocating his family to St. Joseph, Missouri. A devoted wife, Lizzie followed Jackson across the country for the next thirty eight years, living the difficult life of an army wife in the American frontier. She and Jackson had no children.[12]

Captain Jackson commanded C Troop for over twenty years seeing service from the Canadian border in the Northwest to the Mexican border in the Southwest. Promotions came excruciatingly slow in the frontier army but Jackson finally became a field grade officer at the age of fifty-nine when he was promoted to Major in the 3rd Cavalry on 27 August 1896. Major Jackson saw active campaigning with his new regiment during the Spanish-American War, where they participated in the assault on San Juan Ridge, 1 July 1898, and where sixty-one-year-old Jackson was cited for gallantry while commanding the regiment’s 2nd Squadron of troops C, E, F and G. Following the war with Spain, promotion or retirement came rapidly, and to the aged veterans of the Civil War, both. Jackson was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel of the 5th Cavalry Regiment in January 1900 and served in that capacity for over a year. Based on his later assertion that he was born in 1837, not 1835, Jackson was rapidly approaching the age of retirement by law. Two days before turning sixty-four he was promoted to Colonel and retired on this birthday. Henry Jackson and his wife, Lizzie, retired to Leavenworth, Kansas where he entered the banking business serving as the vice president of the State Savings Bank and later the Army National Bank. Three years after his retirement from the army, Jackson was promoted from the retired list to Brigadier General. He died of cancer in 1908 but only a few papers across the country announced his passing.[13]

Leavenworth, Kan., Dec. 9.–Brigadier General Henry Jackson, retired, died at his home here tonight of cancer, aged 71 years.

General Jackson was a soldier in the Crimean war, Civil war, the Spanish-American war and Indian campaigns. He was born in Canterbury, England. When 16 years of age he enlisted as a soldier and was in the Crimean war. Rising to the rank of lieutenant in the English army, he resigned and came to America. He enlisted in the Fourteenth Illinois cavalry in 1863. He was commissioned first lieutenant after the Civil war and in 1876 was made captain. In 1898 he was advanced to major. In 1900 he was made lieutenant colonel, and in 1901 a colonel. He retired in 1904 with the rank of brigadier general.[15]

Less than two months later on 2 February 1909, General Jackson’s faithful partner of almost four decades, Lizzie Calhoun Jackson, joined him in death and was buried by his side in the Fort Leavenworth National Cemetery.[16]

Brigadier General Henry Jackson and his wife, Elizabeth, are buried at the Fort Leavenworth National Cemetery.[16]

Endnotes

[1] This picture of Captain Henry Jackson is cropped from a larger photograph of the officers of the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment, in camp at a target range at Fort Riley, Kansas about 1888. The picture is from the author’s private collection.

[2] Interestingly, Hare may have been one of the only officers in the post-Civil War army to be twice promoted following the death of a fellow officer killed in action against hostile Indians. He was promoted to First Lieutenant effective 25 June 1876 to fill the vacancy created when Lieutenant James Porter was killed at the Little Big Horn, and he was promoted to Captain effective 29 December 1890 to assume Captain George Wallace’s position when that officer was killed at Wounded Knee.

[3] John B. Turney, Letter to Mary Ellen Maloney Turney, 18 Dec 1890. Original letters in possession John F. Turney of Alamogordo, New Mexico, with express permission to post to this website.

[3] Jacob F. Kent and Frank D. Baldwin, “Report of Investigation into the Battle at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota, Fought December 29th 1890,” in Reports and Correspondence Related to the Army Investigations of the Battle at Wounded Knee and to the Sioux Campaign of 1890–1891, the National Archives Microfilm Publications (Washington: The National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration, 1975), Roll 1, Target 3, Jan. 1891, 686.

[4] Ibid., 687.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid., 687-689.

[7] Ibid., 689.

[8] Henry Jackson, letter to the Adjutant General dated 15 Jan 1866, from Peter Russell, “A Benteen ‘Coffee Cooler’,” Men With Custer, http://www.menwithcuster.com/29/ accessed 25 Jan 2014.

[9] Peter Russell, “A Benteen ‘Coffee Cooler’,” Men With Custer, http://www.menwithcuster.com/29/ accessed 25 Jan 2014.

[10] Adjutant General’s Office, Official Army Register for March 1891, (Washington: Adjutant General’s Office, 1891), 73; Kenneth Hammer, Men With Custer: Biographies of the 7th Cavalry, (Old Army Press, 1972), 174.

[11] John C. Power, History of the Early Settlers of Sangamon County, Illinois, (Springfield: Edwin A. Wilson & Co., 1876) 167-169.

[12] Ibid.; Fitzhugh Lee, Cuba’s Struggle Against Spain, (New York: The American Historical Press, 1899), 507; United States Cavalry Association, “Historical Sketch of the Operations of the Third Cavalry During Its Tour Abroad, April 1898 to November 1902,” Journal of the United States Cavalry Association, Vol. 14, 314.

[13] Peter Russell, “A Benteen ‘Coffee Cooler’,” Men With Custer, http://www.menwithcuster.com/29/ accessed 25 Jan 2014.

[14] The Salt Lake herald., (Salt Lake City, Ut.) December 10, 1908, Page 2, Image 2, http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85058130/1908-12-10/ed-1/seq-2/ accessed 19 Jan 2014.

[15] Ancestry.com, U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962[database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012; National Archives and Records Administration, Burial Registers of Military Posts and National Cemeteries, compiled ca. 1862-ca. 1960, Archive Number: 44778151, Series: A1 627, Record Group Title: Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774-1985, Record Group Number: 92.

[16] Joyce Nance-Woodcock, photo., “Henry Jackson,” FindAGrave, http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=3657721 accessed 23 Jan 2014.

Citation for this article: Samuel L. Russell, “Captain Henry Jackson, Commander, C Troop, 7th Cavalry,” Army at Wounded Knee (Sumter, SC: Russell Martial Research, 2013-2014, http://wp.me/p3NoJy-on), posted 25 Jan 2014, accessed __________.

Mr Russell, you say that Henry Jackson ‘established’ his date of birth as 31 May 1837. Do you mean he ‘claimed’ that this was his date of birth, which is not at all the same thing. Also, based on over 45 years experience as an amateur genealogist I find it strange that the details of his birth cannot be corroborated and the fact that no one matching his personal details appears in the [British] Army List during the Crimean Wars years suggests to me that ‘Henry Jackson’ was almost certainly not the person who he said he was. He may well have served in the Crimean War but not as a commissioned officer. Thank you for quoting my website – http://www.menwithcuster.co.uk/29 – as a source of your information.

LikeLike

Peter… Thank you for your comment, and for your outstanding site on the British Americans that served with Custer. I intentionally used the word “established” to denote that he provided enough evidence–likely not more than a letter of explanation (claim) as in the case of Myles Moylan–that the War Department accepted 31 May 1837 as his date of birth. It was that date of birth that established when he was required by law to retire. I am by no means convinced that it is accurate, and would love to see some documentation from county Kent that backs up his claim. I also am not convinced that Moylan wasn’t really from Ireland as he originally attested. I think you are very likely correct when you assert that Jackson may have served under a different name. His claim of a commission in the British service could also be completely false, unlike his peer, Henry James Nowlan, who is well documented both as graduating from Sandhurst in 1854 and joining the 41st Foot at the Siege of Sebastopol from Templemore, Londonderry, Northern Ireland, in February 1855. Many questions are left unanswered in the case of Henry Jackson.

LikeLike

Thank you. Have been doing research on “Henry Jackson”, as this is my grandfather’s name. It has been very difficult to find any information on this name that also connects to South Dakota and Washington State, at least 2 different sites have denied me access after making the link between the two. I think you just helped me link my ancestors to why I’m as white as I am…. It all makes sense now…. 🌎

LikeLike

My name is James Hamilton McCord IV and I was born in St. Joseph Missouri in 1952. I now reside in Greenwich Connecticut.

Our family records show that Henry Jackson was indeed born in Canterbury England on May 31, 1837. He was married to Elizabeth Calhoun who died on February 2, 1909. Col Jackson and Elizabeth had no children.

Aunt Lizzy as my family referred to her had a sister Susan Parrie Calhoun who was born on September 8 1844 and married Virgil W. Parker on August 29, 1866. They had one daughter, Adele Calhoun Parker.

Adele Parker married my great grandfather James Hamilton McCord Sr. on April 25 1893.

LikeLike

Mr McCord… Thank you for commenting and providing the information. Can you share a copy of the family records to which you refer?

Sam Russell

LikeLike