…when the Indians opened fire it was regardless of the consequences to their women and children and to the inevitable destruction of them.

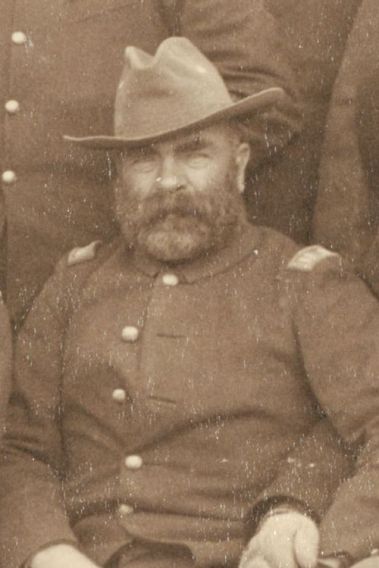

Captain Myles Moylan, A Troop, 7th Cavalry, at Pine Ridge Agency, 16 Jan. 1891. Cropped from John C. H. Grabill’s photograph, “The Fighting 7th Officers.”

Such Was the testimony on January 7, 1891, of the grizzled fifty-two-year-old commander of A Troop, 7th Cavalry, Captain Myles Moylan, arguably the most experienced Indian fighter in the regiment if not the Army. He was the second officer called to testify on the first day of Major General Nelson A. Miles’s investigation into Colonel James W. Forsyth’s actions at Wounded Knee. Upon being sworn by the court, Captain Moylan provided the following testimony.

After the Indian camp was established on the Wounded Knee on the 28th of December, 1890, I was detailed by Major Whitside to take my Troop A, and Captain Nowlan’s Troop I was also ordered to report to me, for the purpose of guarding the Indian village during the night of the 28th and 29th. I had four officers and 81 enlisted men in the guard. I established a line of sentinels around the village, covering it with 20 posts, leaving a small number of men to act as patrols during the night. These posts were on the far side of the ravine south of the village, thence crossing the ravine west and east of the village and also extending on the north side, forming a complete chain, but especially guarding the ravine to the east and west.

On the morning of the 29th, I was ordered by Major Whitside, who commanded my battalion, that at a certain hour the men that were not on post, consisting of about 48 men, would be posted, in the intervals between the sentinels, so as to distribute them equally in that part of the chain to the south and west, so as to strengthen it, so that when the distribution was effected all of the two Troops, except a slight reserve from each Troop, was on the line, their officers in charge of them to superintend.

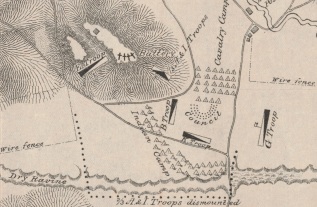

Inset of Lieut. S. A. Cloman’s map of Wounded Knee depicting the scene of the fight with Big Foot’s Band, December 29, 1890.

After the line was complete, I reported to Major Whitside to know what to do with my reserve. He instructed me to hold it until further orders. Subsequently I noticed that Captain Varnum, who was searching the tepees, had not sufficient men to carry away the arms from the tepees as they were found. I took these men down and assisted him in the duty of carrying away the arms to a place by the battery.[1]

The court asked Captain Moylan if his men came under fire from B and K Troops at any time after they were posted between the Indian council and their village.

I don’t think they were. I lost only four men in my Troop, and they were of the guard across and in the vicinity of the ravine to the south and west, and one man of the reserve was killed about half way between the tepees and our camp, and I think these men were killed by Indians.[2]

In response to the courts final question regarding what he knew of the killing of women and children and what precautions were taken to avoid it, Captain Moylan provided the following response.

I think the killing of the women and children was entirely unavoidable, for the reason that when the bucks broke a large number of them made a rush for this ravine and in order to get there they had to pass through the tepees where the women and children were. I would say in addition that I repeatedly heard cautions given by both officers and non-commissioned officers not to shoot squaws or children, and cautioning the men individually that such and such Indians were squaws. The bucks fired from among the squaws and children in their retreat. When the bucks first fired, their shots passed unavoidably through the position occupied by the women and children. This was a fact that I saw distinctly and remarked at the time to Captain Ilsley prior to the firing, saying that the children were evidently apprehensive of no danger, as they were playing about the tepees, and when the Indians opened fire it was regardless of the consequences to their women and children and to the inevitable destruction of them. The firing on the plateau when the Indians made their break was, entirely on the part of our troops, directed on the bucks in the circle and in a direction opposite to the tepees.[3]

Myles Moylan was the son of Thomas and Margaret (Riley) Moylan, and married in 1872 twenty-year-old Charlotte “Lottie” Calhoun, sister of fellow 7th Cavalry officer Lieutenant James Calhoun. She was born June 1, 1852, in Cincinnati, Ohio, the daughter of James and Charlotte (Sanxay) Calhoun. Moylan was orphaned as a teenager, and required a guardian’s permission to enlist in the Army under the age of twenty-one. A probate court for Suffolk County, Massachusetts appointed Moylan’s friend, Christopher Leonard from Boston, as his guardian on June 8, 1857, and Moylan enlisted the same day joining the 2nd Dragoons.[4]

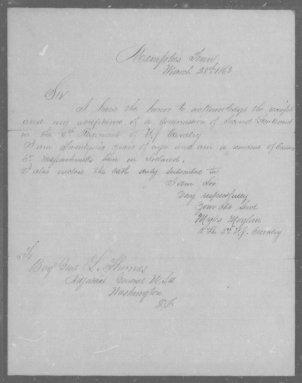

(Click to enlarge) Myles Moylan’s letter accepting a commission in the 5th Cavalry. He states that he was born in Ireland.

Moylan’s date and place of birth was a source of discrepancy that he was required to formally address to the Adjutant General of the Army several times during his career, he being the source of confusion. When Moylan enlisted in the Army in June 1857 he stated that he was a twenty-year-old shoemaker born in Galway, Ireland. By his own later testaments he was actually eighteen. He reiterated that Ireland was his country of birth in 1863 in a letter to the Adjutant General accepting a commission in the 5th Cavalry, “I am twenty-six years of age and am a resident of Essex Co., Massachusetts born in Ireland.”[5] Both the enlistment record and letter to the Adjutant General put his year of birth as 1837 in Galway, Ireland. After being dismissed from the Army in October 1863, Moylan reentered under the alias Charles E. Thomas. Using this assumed name, Moylan avowed in 1865 that “I was born in Amesbury in the state of Massachusetts. I am twenty-eight, 28, years of age.”[6] This changed his country of birth and still indicated he was born in 1837. In 1866, Moylan wrote for the commissioning board a brief statement of his service up to that point and settled the issue of his place of birth to the satisfaction of the Adjutant General, “I, Myles Moylan, was born in Amesbury in the state of Massachusetts, on the 17th of December 1838. I resided in Massachusetts until June 1856 when I enlisted in the U.S. Army and was assigned to the 2nd Regiment of Dragoons.”[7] Because officers were required to retire at age sixty-four, Moylan in 1883 had to explain the discrepancy of his year of birth and established it as 1838, not 1837. “At the date of my enlistment, June 8th, 1857, and also when I accepted my appointment as 2d Lieutenant 5th Cavalry, March 28th, 1863, I was in doubt as to my exact age.”[8] The truth of his date and place of birth likely lies undiscovered in a birth or Christening record in Amesbury, Massachusetts, or Galway, Ireland.

Myles Moylan’s career in the cavalry was singularly impressive, from his service with the 2d Dragoons in the antebellum army, to his exploits during the Civil War with the 2d U.S. Cavalry, 5th U.S. Cavalry, and 4th Massachusetts Cavalry, to his service in the storied 7th Cavalry. In 1883, one of Moylan’s contemporaries, Captain George F. Price of the 5th Cavalry, compiled a history of that regiment which included the following summation of Moylan’s career up to about 1882. I include it here in its entirety, as it is one of the most concise yet inclusive biographies of Moylan’s service that I have come across, and because it was written by an officer with whom Moylan served.

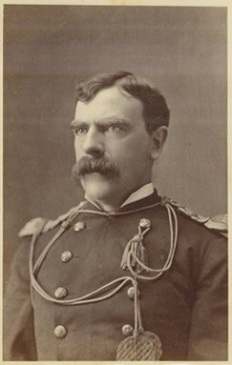

The back of this photograph reads, “Yours very truly, M. Moylan, Fort A. Lincoln, D.T., Oct. 20/76.”

Myles Moylan was born in Massachusetts. He served as a private and non-commissioned officer in the Second Dragoons (present Second Cavalry) from June 8, 1857, to March 28, 1863, when he was discharged as a first sergeant, having been appointed a second lieutenant in the Fifth Cavalry, to date from February 19, 1863. He served as a non-commissioned officer in Kansas and with the Utah expedition, 1857-58; in Nebraska from July, 1859, to September, 1860, and was engaged in the action with hostile Kiowas at Blackwater Springs, Kan., July 11, 1860. He participated in General Lyon’s campaign in South-western Missouri, and was engaged in the battle of Wilson’s Creek. He was then transferred to Tennessee, and participated in the capture of Forts Henry and Donelson, and was engaged in several skirmishes with the enemy preceding the capture of the forts. He was also engaged in the battle of Shiloh, the siege of Corinth, the affair at Pocahontas Farm, and the battle of Corinth.

He joined the Fifth Cavalry in May, 1863, and was a company commander during the entire period of his service with the regiment, and participated in the battle of Beverly Ford (distinguished for gallantry), the skirmish at Aldie, the actions at Middletown and Snicker’s Gap, near Upperville; the battle of Gettysburg, the actions at Williamsport, Boonsboro, Funkstown, and Falling Waters, the engagement of Manassas Gap, the skirmish near Front Royal, the action near, and battle of, Brandy Station, and the action at Morton’s Ford. He was out of commission, to date from October 20, 1863. He re-entered the service in the Fourth Massachusetts Volunteers, where he served as a private and sergeant from December 2, 1863, to January 25, 1864; as a first lieutenant from the 25th of January to the 1st of December, 1864; and as a captain from December 1, 1864, to November 14, 1865, and participated in the actions on John’s Island, S. C. (July, 1864), and near Jacksonville, Fla. (October, 1864), and commanded two companies of the regiment at the headquarters of the Twenty-fourth Army Corps during the closing Richmond campaign of 1865, and was made a brevet major of volunteers, to date from April 9, 1865, for gallant and meritorious services during the last campaign in Virginia. He enlisted in the mounted service January 25, 1866; was assigned to the Seventh Cavalry August 20, 1866, and served as sergeant-major from the 1st of September to the 16th of December, 1866, when he was discharged, having been appointed a first lieutenant in that regiment, to date from July 28, 1866. He was regimental adjutant from February 20, 1867, to December 31, 1871 (relieved at his own request), and was promoted a captain March 1, 1872.

He has been employed in Kansas, Kentucky, Dakota, and Montana during the past sixteen years, having stations at Fort Leavenworth, Elizabethtown, Forts Rice, Lincoln, Randall, and Meade, and was engaged in the brilliant action at the Washita (November 27, 1868), in the combat (commanding a squadron) with hostile Sioux on Tongue River (August 4, 1873), in the action on the Big Horn River (August 11, 1873), in the Black Hills expedition of 1874, in the disastrous action on the Little Big Horn River (June 25, 1876), and in the combat at Bear Paw Mountain (September 30, 1877), where he was wounded. He also served as acting assistant adjutant-general of the troops operating against hostile Indians in Kansas, 1868-69, and was employed on recruiting service from January, 1871, to January, 1873. He commanded a battalion (three companies) on the Little Missouri River during the early summer of 1881, and is now serving as a company commander at Fort Meade, Dak.[9]

As a further testament to his reputation across the Army, Regimental Adjutant, Lieutenant J. Franklin Bell, provided the following remarks in May 1892 at a ceremony in which the officers of the 7th Cavalry bid farewell to the newly promoted Major Moylan and his wife, Lottie Calhoun, as they prepared to depart for Fort Assiniboine with the 10th Cavalry.

We, who welcome you here tonight, are proud to flatter ourselves that we belong to one of the best organizations in the service. Its reputation is not the creature of an hour, nor of a day, but has been making for the last twenty-six years, and the only unchanging factors in its growth during all these years have been a few of its officers. It needs no argument from me in this assemblage to establish the claim that the character of an organization depends upon its leaders, nor will any one who knows dispute that Major Myles Moylan has, during his long and continuous service with his regiment, contributed as much as any other individual to the making of its good reputation and fair name.

Arriving with its first batch of recruits, he was its adjutant, and consequently in its very beginning occupied a position which afforded him an opportunity of incorporating some of his own military ideas and principles into its growing character. This same characteristic of determination and perseverance toward regularity and accuracy of detail which laid the foundation of the excellent regimental records we now possess, enabled him for the last twenty years to maintain in our midst an organization fit to serve as a model for all. The military example set for young officers by this man has been no ordinary one. It may not be said of every soldier that when absent, whether for pleasure, duty or business, field orders for his regiment always signaled his immediate return, poste haste, to join his troop. Not every one can claim the proud distinction of having participated in every campaign his regiment ever made. Major Moylan has been present in every fight a regiment, famous for the number of its engagements, ever had, save one. He missed standing shoulder to shoulder with his fellows at Canon creek only because he was at the time hastening to the field of the bloody Bear Paw battle, where in a conflict with the same savage foe two of his brother officers were killed, himself and another wounded, while only one escaped unhurt.

This is no ordinary record, and yet the half is still untold, for Major Moylan measured weapons with Indians on these plains before the civil war and in that great and sanguinary struggle fought on many a hard contested field for the preservation of the union.[10]

The Major Myles Moylan House is a registered National Historic Landmark in San Diego, California. From Wikimedia Commons.

Less than a year after his promotion to major, Moylan requested to be retired following thirty-five years of almost continuous service and that he be allowed to proceed to his home in San Diego, California. The War Department approved his retirement on April 15, 1893, and he and his wife, Lottie Calhoun, settled into their west coast home.[11]

A year after his retirement Moylan received delayed recognition for his actions at the Battle of Bear Paw Mountain in 1877. Congress passed a law in February 1890 authorizing the President to award brevet promotions for gallant service during Indian campaigns. In May 1890, Major General Nelson A. Miles recommended several officers for gallantry from his 1877 campaign against the Nez Perce Indians. Three months later the recommendation was endorsed by Major General Alfred Terry, and the Adjutant General indicated that Major General John M. Schofield, Commanding General of the Army, would recommend a brevet. The request remained dormant for several years, finally being forwarded by President Grover Cleveland in April 1894.[12] The original recommendation included the following extract from General Sheridan:

On September 30, 1877, at seven o’clock in the morning, after a march of two hundred and sixty-seven miles, Colonel Miles’ command was upon the trail of the Nez Perces, and their village was reported only a few miles away. It was located within the curve of a crescent-shaped cut bank in the valley of Snake Creek, and this, with the position of some warriors in ravines leading into the valley, rendered it impossible for his scouts to determine the full size of strength of the camp. The whole column, however, advanced at a rapid gait, the leading battalion of the 2nd Cavalry being sent to make a slight detour attack in the rear, and cut off and secure the herd. This was done in gallant style, the battalion, in a running fight, captured upwards of eight hundred ponies, the battalions of the 7th Cavalry and the 5th Infantry, charged and mounted, directly upon the village…. In the first charge by the troops, and during the hot fighting which followed, Captain O. Hale, 7th Cavalry, Lieut. J. W. Biddle, 7th Cavalry, and 22 enlisted men were killed…. Captains Moylan and Godfrey, 7th Cavalry, First Lieuts. Baird and Romeyn, 5th Infantry and thrity-eight men were wounded…. During the fight with Colonel Miles’ command seventeen Indians were killed and forty wounded. The surrender included 87 warriors, 184 squaws and 147 children.[13]

General Miles recommendation of 1890 went on to state:

Captain Myles Moylan, 7th Cavalry, senior surviving officer of that portion of the 7th Cavalry which took part in action at Bear Paw Mountains, M. T., September 30, 1877, in his report dated August 16, 1878 says: ‘Having established my line I report to Captain Hale for further instructions and was in the act of receiving orders from him when I was shot through the upper part of the right thigh and had to be taken from the field.'[14]

At his retirement home in San Diego in June 1894, Moylan received his belated brevet promotion to Major for his actions almost seventeen years earlier. That was not to be his last recognition for his services at Bear Paw Mountain. Later that same year he was awarded the Medal of Honor on November 27, 1894. His citation read:

Maj. Myles Moylan, U.S. Army retired, wearing his Medal of Honor, circa 1894.

The President of the United States of America, in the name of Congress, takes pleasure in presenting the Medal of Honor to Captain Myles Moylan, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism on 30 September 1877, while serving with 7th U.S. Cavalry, in action at Bear Paw Mountain, Montana. Captain Moylan gallantly led his command in action against Nez Perce Indians until he was severely wounded.[15]

Writing to Brigadier General James W. Forsyth in 1896, Moylan provided his former commander with details regarding his role in the regiment’s fight at the Drexel Mission along the White Clay Creek on 30 December 1890. Forsyth was compiling an official record of the regiment’s actions at Wounded Knee and White Clay Creek to send to Secretary of War Daniel Lamont and had corresponded with many of the officers that served under him at Pine Ridge. Commenting on Forsyth’s statement of the battle of White Clay Creek, Moylan provided the following response.

Sir: I have carefully read the papers and examined the map sent me by you and so far as my knowledge goes the proposed statement to the Secretary of War concerning the Drexel Mission fight is a very clear and succinct statement of the facts in regard to that affair.

The following details touching my own part in the matter may be of service in clearing up uncertainties. I was in command of the Advance Guard and after proceeding about half a mile beyond the bridge I received orders to halt and had done so when Lieut. Preston, who with his scouts was in advance of me, fired a few shots and called for a troop to drive some Indians away from hills occupied by them. The troops were then stationed, my own, (Troop A.) and troop I, on commanding hills somewhat in advance of the rest.

During the retirement, my troop and troop B, were ordered to retire from a good position and the Indians immediately started to take it themselves, whereupon we were ordered to return and re-take the position, which we did, driving the Indians away.

Subsequent to this, Major Whitside withdrew two troops of his battalion and sent me word to follow him across the bridge to the rear. I did so and coming near Major Henry, he asked me, “Where are you going?” I replied, “There is my commanding officer,” (pointing towards Major Whitside) “he can tell you.”

The Indians Lieut. Preston refers to in his testimony as being “on the bluffs on the right going down stream” who were firing on the troops near the shack, were among the foot hills down in the bottom in a position to the right and slightly to the front of my troop, while I was in its most advanced position. They fired a few shots at us from there but they were at such long range that I would not let my men fire. Capt. Jackson’s troop was afterwards sent to a position to our right, facing these Indians, in order to prevent their advance along those bluffs for Major Henry’s command soon arrived and drove them away from where they then were. There never were, to my knowledge, any Indians on the bluffs to our right and rear where indicated on Col. Heyl’s map. If they had been there, they would have been at too long range to have done us damage.[16]

The city of San Diego was proud of the decorated war hero that had chosen their city for his retirement. As the Nation prepared for war with Spain, the San Diego Chamber of Commerce wrote to President William McKinley:

…urgently recommends Major Myles Moylan, U.S.A., retired, for appointment to Brigadier-General of Volunteers from California. His is not a politician. Served in a distinguished capacity before and since the war of the rebellion in the 7th Cavalry, U.S. Army. Wears a badge from Congress for distinguished gallantry in the Indian Wars and the campaigns with Custer and General Miles. Is physically, mentally and professionally well-equipped for the position, as the records of the War Department will show, and has been a resident of this city since retirement in 1893.[17]

Whether or not the fifty-nine-year-old Moylan actively sought the appointment is not recorded, and he did not serve during the Spanish-American War. He remained in San Diego for the last decade of his life, serving actively with the California Commandery of the Military Order of Loyal Legion of the United States, a fraternal organization of officers that had served in the Union Army during the Civil War. He died of stomach cancer one week shy of his seventy-first birthday on December 11, 1909, and was buried in Greenwood Memorial Park in San Diego. His wife, Lottie, joined him in death in 1916. They had no children.[18]

Major Myles Moylan is buried in Greenwood Memorial Park in San Diego, California.[19]

Endnotes

[1] Jacob F. Kent and Frank D. Baldwin, “Report of Investigation into the Battle at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota, Fought December 29th 1890,” in Reports and Correspondence Related to the Army Investigations of the Battle at Wounded Knee and to the Sioux Campaign of 1890–1891, the National Archives Microfilm Publications (Washington: The National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration, 1975), Roll 1, Target 3, Jan. 1891, 664 – 665 (Moylan’s testimony dated 7 Jan 1891).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ancestry.com, 1860 United States Federal Census [database on-line], Year: 1860, Census Place: Cincinnati Ward 15, Hamilton, Ohio, Roll: M653_977, Page: 400, Image: 195, Family History Library Film: 803977; United States Department of Interior, “Major Myles Moylan House,” National Register of Historic Places–Nomination Form, http://pdfhost.focus.nps.gov/docs/NRHP/Text/84001181.pdf accessed 15 Sep 2013; Ancestry.com, U.S. Army, Register of Enlistments, 1798-1914 [database on-line], Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2007.

[5] National Archives Microfiche Publication M1395, “2090 ACP 1873: Moylan, Myles,” Letters Received by Commission Branch, 1874-1894, 12.

[6] Ibid, 16.

[7] Ibid., 33-34.

[8] Ibid., 109.

[9] George F. Price, comp., Across the Continent with the Fifth Cavalry, (New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1883), 558-560.

[10] Associated Press, “Farewell to Major Myles Moylan,” The Omaha Daily Bee, 16 May 1892, 8.

[11] National Archives Microfiche Publication M1395, “2090 ACP 1873: Moylan, Myles,” Letters Received by Commission Branch, 1874-1894, 187 and 194.

[12] Ibid., 113; United States Congress, Journal of the Executive Proceedings of the Senate of the United States of America, Fifty-Third Congress from August 7, 1893, to March 2, 1895, Vol. XXIX in two parts, Part 1, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1909), 597 and 601.

[13] National Archives Microfiche Publication M1395, “2090 ACP 1873: Moylan, Myles,” Letters Received by Commission Branch, 1874-1894, 114.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Military Times Hall of Valor, “Myles Moylan,” http://projects.militarytimes.com/citations-medals-awards/recipient.php?recipientid=2426 accessed 15 Sep 2013.

[16] Miles Moyal to James W. Forsyth dated 10 Apr 1896, James W. Forsyth Papers, 1865-1932, Series I. Correspondence, Box 1, Folder 1 – Box 2, Folder 49, The Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Libraray, Yale University Library.

[17] National Archives Microfiche Publication M1395, “2090 ACP 1873: Moylan, Myles,” Letters Received by Commission Branch, 1874-1894, 218

[18] Ibid., 237.

[19] Ceme Terry, photo., “Capt Myles Moylan,” FindAGrave, http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=5929202 accessed 15 Sep 2013.

Citation for this article: Samuel L. Russell, “Captain Myles Moylan, Commander of A Troop, 7th Cavalry,” Army at Wounded Knee (Sumter, SC: Russell Martial Research, 2013-2015, http://wp.me/p3NoJy-84), updated 11 Oct 2014, accessed date ________.

While reviewing a microfilm of the James W. Forsyth papers that I obtained from the Beinecke Rare Book Room and Library, I rediscovered a letter from Myles Moylan to James Forsyth in which he provides his recollections of the battle at White Clay Creek. I have updated this post to include that letter.

LikeLike

I have a 1860 springfield 45-70 rifle that was cut back with tanned skin wrapped around it.,A 7th cavalry “A” company insignia and the word RED ELK written with brass tacks on the stock and beads wrapped around the barrel. It came from an Indian from Wounded Knee area of South Dakota, this Indian had given this rifle to a farmer friend of his. I purchased it from and individual who had tried to buy this rifle from the farmer several times over a period of time, and the farmer refused to sell it. The individual purchased it at this farmers estate sale after he had passed away.

I left the rifle with my brother who collected Indian Artifacts and he had other collectors look at this rifle, “QUOTE” they said the tanning of hide it was wrapped with was real, the beads “MAY” have came from a small country over sea’s that made these small beads that the Indians liked (He mentioned the name of the country but I can not remember the name of it.) He also said that the rifle had been fire like a pistol because the way the tanned hide on the pistol grip had formed to indicate this. This is the way they would shoot Buffalo from a horse with a gun that did not have a front sight.

Any information on this item would be appreciated (richardhalvorson@yahoo.com)

LikeLike

Mr. Halvorson… Thank you for your comment. I have not come across any information regarding rifles that may have been lost, stolen, or abandoned on the field at either Wounded Knee or White Clay creeks. There are several Lakota accounts that retell of some of tribes people securing cavalry weapons from wounded or killed soldiers as the Indians fled into the ravine. Perhaps one of my readers can provide some information.

LikeLike

Good old uncle Myles.

LikeLike

HI Sam,

It was good to see and read some of the articles on your page. I am working on a series of books and articles on other members of the Custer clique, via the Calhoun family connections. Maybe we could chat sometime soon and compare notes. I do not have much on Wounded Knee, but I may be able to provide other links for you.

Jeff

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mr. Davis… Thank you for commenting, and I always welcome collaboration on most anything having to do with the frontier Army.

LikeLike

Would you have time to talk tomorrow or the next day? Send me an email and we can make arrangements. My email address is: president@vbma.us, or jddavis@rocketmail.com.

Thanks,

Jeff

LikeLike

Sam,

Myles Moylan was born to Thomas Moylan and Margaret Reilly who lived on the Mall in Tuam, Co Galway rather than in Amesbury, MA. They were married on Dec 4, 1814. The record is available at https://registers.nli.ie/registers/vtls000632077#page/169/mode/1up – 8th down on the left-hand side.

Thomas died in 1858 and is buried with Myles’s brother John in Claretuam Cemetery outside Tuam. Margaret was still alive until at least 1868.

According to Myles’s enlistment record which is available at U.S. Army Register of Enlistments, 1798-1914, he was a shoemaker who was born in Galway.

According to the Massachusetts U.S, State Census 1855, he was a shoemaker who was born in Ireland. He emigrated to West Newbury where his two older brothers Thomas and Patrick lived.

In 1884, the West Newbury Messenger carried a report about Myles visiting his brother Thomas there.

The Evening Mail (Stockton, California), 29 Apr 1901, reports a meeting between himself and his cousin John Moylan/Milan – the last time they met was sixty years previously in their birthplace in dear old Ireland.

The Tuam Herald carried a piece about Myles in 1876 shortly after the Little Bighorn, connecting him to the son and grandchildren of Thomas Moylan and Margaret Reilly from the Mall in Tuam.

When Myles enlisted under the alias Charles E Thomas he cited Amesbury as his place of birth and in time that was taken as fact.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mairéad O’Brien… Thank you for the comment. As you can see in this post, Moylan’s actual place and year of birth is questionable, and not a settled question for historians, even if it was settled to the A.G.O.’s satisfaction. In addition to the Charles Thomas enlistment, Moylan twice certified to a commissioning board in 1866 and 1867 that he was born in Amesbury, Mass.

https://www.fold3.com/image/303431593

His parents’ marriage record, and the news articles you mention add to the weight of his being born in Ireland, but short of a birth certificate or record, his actual place of birth will continue to be questioned by historians. Personally, I believe he was born in Ireland, and would love to come across a birth record that settles the issue.

LikeLike

Sam, thank you for taking the time to reply to me. Yes, he has claimed to have been from Amesbury more than once but only after a certain date. It’s as if he saw a chance to throw off his Irish heritage at a time when it wasn’t great to be Irish.

I have tracked all Myles’s siblings except for Michael. The fact that Myles’s cousin referred to him as Michael put me thinking that Myles could actually be this Michael. I wouldn’t have thought that Myles and Michael were interchangeable but perhaps Myles didn’t want to be called Michael at a time when ‘Mick’ was a derogatory reference to Irish people. From Myles’s submission on the 1855 Census and his 1857 Enlistment Record, the earliest he was born was 1835/36. Michael was born in August 1832. That’s a fair discrepancy at a young age. In Irish records, the gap between the actual age and the perceived age often widens with time. Two of his older brothers emigrated to West Newbury before he did and their estimation of their ages was pretty accurate.

I have been onto the Congressional Medal of Honour Association and whereas they can see merit in my arguments, the decision has to come from the army – I’m working on that. I may never get beyond creating doubt as to whether Amesbury is his place of birth.

Regards,

Mairéad O’Brien

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Sam,

I hope you don’t mind but I’m back again arguing the toss about Myles Moylan’s place of birth.

I have attached some original records etc to Myles’s Findagrave site. If you open the profile of John, Myles’s brother you will find a report from July 22nd 1876 that was published in the Tuam Herald just a few weeks after the Battle of the Little Bighorn. It connects Myles to his late brother John and his nephews who were still living in Tuam. John was a well-to-do auctioneer and pawnbroker and was a town commissioner for a few years. If you open the profile of Thomas, Myles’s father who died in 1858 you will find the 1814 marriage record for Thomas Moylan and Margaret Reilly. I’m not sure when Margaret died but she was still alive in 1868 – she was a beneficiary of her daughter-in-law’s will in 1868. The Moylan family who remained in Tuam died young from TB. Myles’s nephews who remained in Tuam were all dead by the age of 30. His nephew Brother Michael Titus Moylan – 5th Superior General of the Christian Brothers left Tuam and although he died from TB, he lived longer than his siblings.

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/5929202/myles-moylan

The Journal of the Old Tuam Society (https://catalogue.nli.ie/Record/vtls000237091) published an article last month on The Moylans of Tuam which outlined the careers of Tuam people Myles and his nephew Brother Michael Titus.

The United States Army Medals of Valor site has Ireland as his place of birth – https://www.army.mil/medalofhonor/citations3.html#M

The National Park Service has Galway as his place of birth – see page 6. https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/69ea5bb8-ba8d-49aa-8a4e-3b887ee086e2

Regards,

Mairéad O’Brien

LikeLiked by 1 person