Tritle received a slight wound in right hand, but continued in his efforts to dislodge the Indians until disabled by a severe wound in right shoulder.

–Adjutant General’s Office

Sergeant John F. Tritle, at thirty-four, had been a cavalry trooper for seven years having completed five years in the 2nd Cavalry before joining Captain Ilsley’s E Troop in 1888. Tritle’s actions at the ravine at Wounded Knee set him apart from every other trooper. He was the only soldier recommended for a Medal of Honor and a Certificate of Merit. The cavalry sergeant’s exploits on that sanguinary 29th of December were highlighted in an article in early February 1891 originally printed in The Washington Star and republished in papers across the country.

Sergeant Tritle, of E Troop, has what some folks would call “grit.” His first wound was in his left hand, and a minute or two later he got another bad one in the hip. That would have satisfied the average warrior, but the sergeant was not inclined to retire. Just then Sergeant Nettles was killed almost at Tritle’s side. Tritle saw the Indian who fired the fatal shot, and, although his own left hand was shattered and blood was pouring steadily from his hip, he said: “I’ll get that Indian.” He did, and an instant later a hostile bullet penetrated his left breast. “I guess I’ll get these wounds dressed now,” was his faint remark as he crawled for the rear. He will almost surely recover.[1]

The article made for good copy, but typical of journalism of the day was inaccurate on several points. Tritle was not shot in the hip, and was wounded in the right shoulder rather than the left breast. His action did however impress his officers. The following month as Lieutenants Sickel and Rice compiled their recommendations for accolades for their troopers Sergeant Tritle stood out. The Adjutant General’s Office provided the following summation of the two lieutenants’ recommendations concerning Tritle, one of five men included in the first group of E Troop Medal of Honor recommendations.

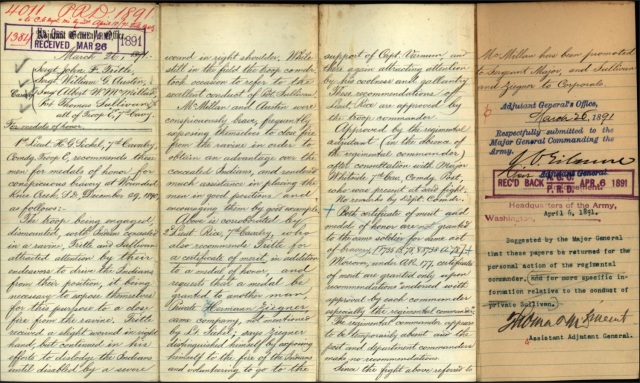

1st Lieut. H. G. Sickel, 7th Cavalry, Comdg, Troop E, recommends these men for medals of honor for conspicuous bravery at Wounded Knee Creek, S.D., December 29, 1890, as follows:

The troop being engaged, dismounted, with Indians concealed in a ravine, Tritle and Sullivan attracted attention by their endeavors to drive the Indians from their position, it being necessary to expose themselves for this purpose to a close fire from the ravine. Tritle received a slight wound in right hand, but continued in his efforts to dislodge the Indians until disabled by a severe wound in right shoulder.

Above is corroborated by 2d Lieut. Rice, 7th Cavalry, who also recommends Tritle for a certificate of merit, in addition to a medal of honor….[2]

(Click to enlarge) The Adjutant General’s Office returned Lieutenant Horatio G. Sickel’s original recommendations in order to obtain additional details and an endorsement from Colonel James W. Forsyth.[3]

(Click to enlarge) The Army Regulations in 1889 provided minimal guidance on criteria for award of a Medal of Honor. By contrast, the specified criteria for award of the little known Certificate of Merit was specifically for gallantry in action.[4]

Apparently Lieutenant Rice was so impressed with Sergeant Tritle’s actions at Wounded Knee that recommending him for a Medal of Honor was not sufficient; the cavalry lieutenant felt his non-commissioned officer also was deserving of the Certificate of Merit, which would entitle the soldier to an additional two dollars each month for the remainder of his enlisted service while receipt of a Medal of Honor provided no additional entitlements. Writing in his original recommendation of March 18, Lieutenant Rice stated, “Sergt. Tritle showed marked skill, efficiency and coolness while his troop was engaged in clearing out a pocket in a ravine in which a number of hostile indians [sic] had taken shelter. Occupying an advanced and exposed position he drew on himself a large part of the hostile fire and entirely unmindful of his own danger he encouraged the men on to action, and not withstanding the fact that he had been wounded in the hand, he made an attempt to cross the ravine in order to more fully observe the enemy when he received a severe wound in the shoulder from which he is still suffering.”

The Adjutant General’s Office correctly pointed out that regulations prohibited a soldier from being awarded both accolades for a single action. The regulations also stipulated that recommendations for certificates “must be indorsed with approval by each commander, especially the regimental commander.” As Sickel and Rice’s recommendations were only endorsed by the 7th Cavalry’s adjutant, the stipulation regarding Rice’s Certificate of Merit recommendation likely was the cause of all of the E Troop Medal of Honor recommendations being returned to the regiment specifically to garner Colonel Forsyth’s endorsement.

When the recommendations were returned, the Adjutant General’s Office apparently considered only the Certificate of Merit for Tritle. Based on all of the other Medals of Honor awarded during the campaign, Tritle certainly would have been awarded a medal had he not also been recommended for a certificate. The army regulations did not specify an order of precedence between the Medal of Honor and the Certificate of Merit except that the medal was listed in a single paragraph preceding the four paragraphs that detailed the awarding of the certificate. Specifically, the Medal of Honor was for “officers or enlisted men who have distinguished themselves in action,” where as the Certificate of Merit was for “extraordinary acts of gallantry performed by private soldiers in the presence of the enemy.” One likely reason that the Adjutant General’s Office determined that Tritle would be considered for the certificate vice the medal was that in this recommendation the War Department had its first case of a non-commissioned officer for award of the Certificate of Merit. Since the establishment of the certificate during the Mexican War only enlisted privates were eligible recipients. Army regulations were modified in 1890 to accord the accolade to any enlisted service member. The second award summation forwarded to Major General Schofield and on to the Secretary of War mentioned only the Certificate of Merit.[5]

2d Lieut. Sedgwick Rice, 7th Cavy., recommends this man for a certificate of merit for conspicuous bravery at Wounded Knee, S. D., Dec. 29, 1890, says the Sergeant showed marked skill and efficiency while his troop was engaged in clearing out a pocket in a ravine in which a number of hostiles had taken shelter; occupying an advanced and exposed position he drew on himself a large part of the hostile fire and entirely unmindful of his danger he encouraged the men on; then, notwithstanding the fact that he had been wounded in the hand, he made an attempt to cross the ravine in order to more fully observe the enemy, when he received a severe wound in the shoulder from which he is still suffering.[6]

(Click to enlarge) the Adjutant General’s second summation of the award recommendation for Sergeant Tritle only mentioned the Certificate of Merit. [7]

On June 16, Assistant Secretary of War L. A. Grant wrote, “Let the certificate of merit be given,” making Sergeant John F. Tritle the first non-commissioned officer to be so recognized. Announcement of the award appeared in newspapers across the country.[8]

The monetary increase in monthly pay did not last long for the cavalry sergeant. Tritle had returned from Pine Ridge to Fort Riley with the first group of casualties and was admitted to the post hospital on January 6. He was hospitalized for three months and was not returned to full duty until four months later on August 8; he was readmitted on September 20. That fall after a thorough examination of his shoulder following ten months of recovery, Captain Van R. Hoff wrote of Tritle’s wound, “partial loss of function of right shoulder joint due to perforating g[un] s[hot] wound involving humerus. The wound has healed thoroughly, but the man claims that he is unable move his arm as freely as his duties require of him.” Tritle received a disability discharge in November 1891.[9]

Born June 7, 1856, at Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, John Franklin Tritle was the third child of John C. and Nancy (Hassler) Tritle. John, the father, was born on New Year’s Day, 1829, in Franklin County where he spent his entire life. A second generation German-American, he was the third of five children of Frederick and Martha Magdalena (Cook) Tritle. John Tritle and Nancy Hassler, both practicing Lutherans, were married in the early 1850s. She was also a German-American native of Franklin County and the fifth of nine children of Johannes and Catherine Katura (Clugston) Hassler. John Tritle began his adulthood working as a clerk. He served briefly as the postmaster at Jackson Hall and eventually became a farmer. He died at the relatively young age of forty-three, and his real estate was valued in excess of $15,000, a significant fortune in 1870 dollars.[10]

John and Nancy had eleven children. The eldest was Frederick Augustus, born in 1852 and died in 1920; their second child was Mary Kate, the future Mrs. Michael Coble, born in 1854 and died in 1931; next was John Franklin, the subject of this post; Samuel Hassler was next, born in 1857 he died a year later; Anna Mariah was the fifth child born in 1858 and died in 1864; David Hassler was born in 1860 and lived to 1935; Martha Ellen, born in 1862 only lived to her second year; William Essex was born in 1864 and died in 1957; Jennie Hassler, the future Mrs. Charles E. Grove, was born in 1867 and died in 1959; Charlotte, born in 1869, became Mrs. Harry E. Sellers, and was the last surviving Tritle child when she died in 1961; the eleventh child was George, who was born in 1871 and died in December of that same year. John C. Tritle died of diabetes on May 15, 1872, in Chambersburg and was buried in the Grindstone Hill Cemetery. Nancy Tritle survived her husband by more than three decades never remarrying. She remained in Chambersburg attending the First Lutheran Church, and when she passed away on September 16, 1905, Nancy was buried next to her husband and her four children that died in childhood.[11]

John F. Tritle grew up in Franklin County, Pennsylvania, in towns like Guilford, Hamilton, Peters, and Chambersburg. By 1880, his older brother, Fred, had headed west and was working as a farm hand in Kansas. Three years later, John too had gone west and made it as far as Chicago where at the age of twenty-seven he enlisted in the Army for five years on August 14, 1883. He listed his occupation as a laborer, stood five feet, six and a half inches tall, had light grey eyes, dark brown hair, and a light complexion. Tritle was assigned to the 2nd Cavalry and completed his first enlistment as a sergeant at Fort Walla Walla, Washington Territory, with an ‘excellent’ characterization of service.[12]

Tritle returned to the east coast and in less than a month signed up for a second five-year enlistment on September 11, 1888, at Baltimore, this time assigned to Captain Ilsley’s E Troop, 7th Cavalry. Following his medical discharge in November 1891, again as a sergeant with an ‘excellent’ characterization of service, Ilsley wrote a letter of reference for Tritle in which he described the medically disabled non-commissioned officer as reliable and trustworthy. Ilsley went on to say, “He was an excellent soldier, always willing to perform his duty to the best of his ability. On account of a gunshot wound in his shoulder he received at the fight at Wounded Knee, S.D., he was discharged on account of disability. I consider him a loss to the service and would be glad to see him succeed in civil life.”[13]

Less than a month later Tritle applied for a disability pension due to his wounded shoulder. He was examined at the end of March 1892 and granted a pension in September of that year. Perhaps still searching for adequate employment, Tritle received another letter of reference from his old commander in November 1892. By then a major in the 9th Cavalry, Ilsley again detailed Tritle’s bravery at Wounded Knee and added, “No mistake can be made giving him employment, perfectly sober and honest and deserving of any position the Govt. can bestow according to his ability.” Lieutenant Sickel also provided a letter of reference in which he wrote of Tritle, “is personally known to me to be a sober, industrious and upright man, and I recommend him to any one requiring the services of a man of his ability.”[14]

Tritle remained on the pension rolls until August 1893 before opting to return to the military life. Perhaps the depression of 1893 pushed him back into the only profession in which he excelled. On August 18, again in the city of Baltimore, Tritle signed up for his third five-year enlistment. Captain and Assistant Surgeon Charles B. Ewing, who had also been present at Wounded Knee, signed off on Tritle’s enlistment certifying that, “he is free from all bodily defects and mental infirmity which would, in any way, disqualify him from the duties of a soldier.” Tritle was cleared by the Adjutant General’s Office for mounted service after noting on his enlistment record that he had been discharged for medical disability from his previous enlistment. The Army restored the two dollars per month extra pay for his Certificate of Merit, and Tritle received that entitlement for the remainder of his enlisted service. He was assigned to D Troop, 1st Cavalry, and by the final year of his enlistment he was serving as that unit’s first sergeant, the position he held when the regiment deployed to Cuba during the Spanish American War. This wartime setting was what brought out the best leadership qualities in Tritle as reported in a Pennsylvania newspaper, again republished in papers across the country.[15]

On July 1 the First United States Cavalry was thus picking its way to the front and was ordered to deploy its skirmish lines. All the men had not kept their relative distances, and there was a bumping together of companies here and wide separation there. At one time Troop D was pushed across the San Juan River, then recalled, when the line was straightened out and again forced over it. Finally all struck out to reach the crest of the next hill, each in his own way. Among those hurrying forward was First Sergeant John Tritle, of Troop D. He is a native of Chambersburg, Penn., and has been fifteen years in the army. Sergeant Tritle had charge of a squad of sixteen men of his troop. When he reached the crest of the hill he had only a few of his squad with him. He didn’t have time to hunt for the missing ones. Instead he organized a second squad from the unattached soldiers there, some from his regiment and some from other regiments. He stationed his men on the hill, and soon saw a party of about forty Spaniards start away from a blockhouse, dragging a fieldpiece with them.

Here was an opportunity not to be lost. The twenty regulars were lying on the ground. Sergeant Tritle gave them the range, 800 yards, ordered them to fire at will and dropped down alongside them and began shooting. The squad had fired two or three shots for each member and had dropped some Spaniards when a Colonel of another regiment called out:

“Sergeant, cease firing there! Do you know who you’re shooting at?”

“The Spaniards, sir,” Sergeant Tritle replied, jumping to his feet.

“They’re not Spaniards. That’s Colonel Roosevelt and his rough riders.”

“Colonel Roosevelt and his men are over there in that pocket. I saw them a few minutes ago.”

“You’re mistaken! Withdraw your men!” and Sergeant Tritle took his Troop D men and retired. But there was disappointment in that squad of soldiers. As one of them said afterward:

“We had an excellent opportunity of capturing that gun. Why didn’t that Colonel let us go on? If we could have killed half of that procession of scared Spaniards, we could have made the other half drop their gun and run. And, if we once got that gun, maybe we wouldn’t have turned it on the Spaniards!” [16]

Tritle finished the last months of his enlistment as the regiment’s quartermaster sergeant. The 1st Cavalry returned to the United States and encamped at Camp Wikoff, Montauk Point, Long Island, New York. The site was selected for its isolated location so that the returning troops could remain in quarantine until the government was sure they were restored to health following the rampant bouts of yellow fever and malaria that so decimated the troops in Cuba.

An aerial view of Camp Wikoff where the 1st Cavalry Regiment was camped upon return from Cuba. [17]

Tritle did not serve in the Philippines and was assigned in March 1901 to A Troop of the newly formed 12th Cavalry at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, and the following month Tritle was appointed the Regimental Commissary Sergeant. In his new position, Tritle worked in the post commissary, which was situated inside the quadrangle, a two story stone structure with four long walls surrounding a large court yard with a clock tower in the center. The quadrangle had a single entry way through a gated sally port that was guarded around the clock by a watchman.

Tritle’s job operating the commissary placed a great strain on the cavalry trooper; his health declined and he demonstrated noticeable signs of stress including drinking to intoxication when not at work. In the winter of 1902, Tritle went absent without leave for several days. He was treated for stress when he returned, and, given his war record, the command took no action beyond a verbal reprimand. On April 26, the nightwatchman observed Tritle return to the commissary in the evening several hours after the normal closing hours. Tritle frequently worked late most nights and this seemed to be his normal routine, although in retrospect the watchman noted that he thought Tritle was drunk. He observed through a window the sergeant walking around the commissary with a candle. Tritle departed about an hour later and inquired of the watchman the time of day. Tritle failed to show up to work the following morning, and when the commissary corporal opened the store, he quickly noticed that the safe had been broken open. The commissary officer, Captain E. D. Anderson, took inventory of the store and noted about $130 missing from the previous day’s accounts. Tritle did not show up again until May4 .[20]When he voluntarily reported back to the post Tritle was in bad shape and taken to the post hospital. He had no recollection of where he had been the previous week and no recollection of his final day at work. One of the treating physicians later testified of Tritle’s condition that, “He seemed to me to be mentally and physically broken down, and had a peculiar ashy appearance, evidently had lost flesh, and as if he had not eaten a mouthful during the four of five days he was absent. He had considerably the appearance of one insane.”[21] Apparently Tritle went on a drinking binge and experienced a blackout lasting almost a week.

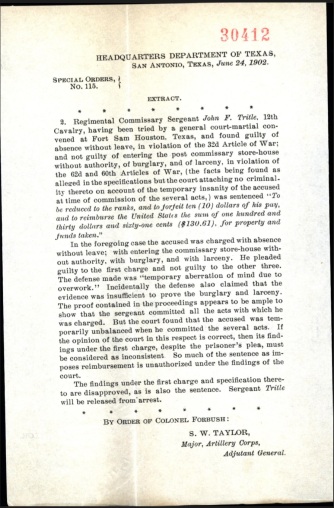

Following an investigation, Tritle was charged with several offenses and a court martial was convened from June 2 to 7, 1902. The charges included absence without leave, conduct to the prejudice of good order and military discipline, burglary, and larceny. Tritle pleaded guilty to being absent without leave and not guilty to the other charges and specifications. The defense made a strong case of no criminal intent due to the defendant’s extreme condition and loss of memory. The defense counsel stated, “The condition in which he returned shows the strain to which his brain was subjected and that he was absolutely irresponsible, and that he was more a subject for a lunatic asylum than for a court-martial.” The court found Tritle guilty of absence without leave, the charge to which he had pleaded guilty, and not guilty to all other charges by attaching no criminality due to his state of temporary insanity. He was sentenced to be reduced in ranks, forfeit ten dollars, and to reimburse the government for the $130 missing from the commissary. In reviewing the court’s sentence, Colonel William C. Forbush, commander of the 12th Cavalry, disagreed with the findings. Forbush determined that if the court found him not guilty of the other charges due to his mental state, then they could not find him guilty of the first charge, even though Tritle had pleaded guilty. The regimental commander disapproved the sentence and restored Tritle to his rank.[23]However, Colonel Forbush was not about to let the sergeant off with no consequences for his actions. Toward the end of June, just two weeks from the end of Tritle’s three-year enlistment, the post surgeon again examined Tritle, who had been in the hospital since his return to post. “I find him to be suffering from ‘Moral insanity’ in my opinion the result of alcoholism.” The major went on to say, “He has been in the hospital since May 4th, and while he talks intelligently, seems to have no memory of what occurred during his absence, and is at all times quiet and somewhat melancholic.” On June 23, the surgeon recommended that Tritle be admitted to the Government Hospital for the Insane in Washington, D. C.[24]

Departing Fort Sam Houston on July 5, Sergeant Tritle was escorted across country and admitted to the government’s mental hospital four days later on July 9, one day after his enlistment term expired. Six days later he was discharged from the hospital and the Army. For the second time in his career the reason for his discharge was a medical certificate of disability, but this time it included the statement, “not in line of duty, being a result of alcoholism.” Regarding his characterization of service, the Adjutant General’s Office referred the matter to the 12th Cavalry commander, who merely forwarded the results of the sergeant’s court martial. In August 1902, a staff officer in the Adjutant General’s Office inquired of the Adjutant General, “As it is shown that the disability (insanity) was the result of the soldier’s excessive use of alcohol shall the remark ‘service not honest and faithful’ and character ‘fair’ be noted on his discharge certificate?” The Adjutant General wrote “yes” on the memorandum.[26]Tritle moved across the country and settled in Seattle, Washington, where he worked as a hostler, caring for the horses of hotel guests. He applied for a disability pension in 1915 for the wounded shoulder received at Wounded Knee. His claim included his discharge papers for all but his final enlistment, all indicating a characterization of ‘excellent.’ The Pension Department stated they could take no action without his final discharge papers, and Tritle dropped the claim. He applied again in 1921 as an Indian Wars veteran with the same result. Finally in 1926 at the age of seventy, Sergeant Tritle was granted a pension of $30 per month for age and as a veteran of the Indian Wars and Spanish American War. By then he was suffering from impaired vision, catarrh, bad teeth, malarial poisoning (from Cuba), piles, callouses, weak arches, and the effects of a gunshot wound of the right shoulder. His pension was later increased to $40 per month, at seventy-seven years of age Tritle received $50 a month, and at age eighty-one it increased again to $55 a month.[27]

On October 18, 1939, at the age of eighty-three, Tritle tripped and fell down the stairs of the hotel where he was living. He fractured his skull and clavicle and died later that day. Never having married, he died intestate and had stated emphatically that he had no living relatives. Tritle had over $1,000 accrued from this pension payments and an attorney was appointed to find any heirs. The lawyer tracked down Tritle’s brother, William, and sisters Jennie and Charlotte, and several nieces and nephews. Not listed among the heirs was Tritle’s namesake. Tritle’s younger brother, David named his first born son after his older brother. Born in 1881, John Franklin Tritle, Jr., lived till 1967.[28]

Quartermaster Sergeant John Franklin Trittle was buried with military honors rendered by the Fortson-Thygessen Camp No. 2, United Spanish War Veterans, of which Tritle had been a member. He was laid to rest in the Veterans’ Memorial Cemetery at the Evergreen Washelli Memorial Park in Seattle. His headstone application listed his rank and unit from his last discharge in which he received an ‘excellent’ characterization of service, with no mention of his role in the 7th Cavalry or distinction at Wounded Knee. The application also misspelled his name by adding an extra ‘T’; the error was transposed onto his marble grave marker. Based on his award of a Certificate of Merit Tritle could have applied to receive the Certificate of Merit Medal created in 1905 and later to have that medal exchanged for a Distinguished Service Cross. Of course had Lieutenant Rice made no recommendation for a certificate, Sergeant Tritle would have been the twentieth 7th Cavalry trooper from the Pine Ridge Campaign to receive the Medal of Honor.[29]

Quartermaster Sergeant John F. Tritle is buried in the Evergreen Washelli Memorial Park at Seattle, Washington. His last name is misspelled with and extra ‘T’.[30]

Endnotes:

[1] “At Wounded Knee; Incidents and Happenings in the Terrible Fight,” The Times (Philadelphia: 9 Feb 1891), 3.

[2] Adjutant General’s Office, Certificate of Merit file for John F. Tritle, Principal Record Division, file 3466, Record Group: 94, Stack area: 8W3, Row: 7, Compartment 30, Shelf: 2. Research conducted by Vonnie S. Zullo of The Horse Soldier Research Service.

[3] Ibid.

[4] War Department, Regulations for the Army of the United States 1889 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1889), 18.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Adjutant General’s Office, Certificate of Merit file for John F. Tritle.

[7] Ibid.

[8] The Salt Lake Herald (24 Jun 1891), 1.

[9] Adjutant General’s Office, Pension file for John F. Tritle, Principal Record Division, file 781, Record Group: 94, Stack area: 7W2, Row: 4, Compartment 13, Shelf: 2. Research conducted by Vonnie S. Zullo of The Horse Soldier Research Service.

[10] Ancestry.com, United States Federal Census [database on-line] (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009), Year: 1850; Census Place: Guilford, Franklin, Pennsylvania; Roll: M432_781; Page: 110A; Image: 226; Year: 1860; Census Place: Guilford, Franklin, Pennsylvania; Roll: M653_1111; Page: 359; Image: 364; Family History Library Film: 805111; Year: 1870; Census Place: Hamilton, Franklin, Pennsylvania; Roll: M593_1346; Page: 333A; Image: 25; Family History Library Film: 552845; Year: 1900; Census Place: Hamilton, Franklin, Pennsylvania; Roll: 1412; Page: 7B; Enumeration District:0045; FHL microfilm: 1241412; Web: Pennsylvania, Find A Grave Index, 1682-2012; U.S., Appointments of U. S. Postmasters, 1832-1971; Historical Society of Pennsylvania; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Collection Name: Historic Pennsylvania Church and Town Records.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Adjutant General’s Office, Register of Enlistments in the U.S. Army, 1798-1914 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives Microfilm Publication M233, 81 rolls), Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1780’s-1917, Record Group 94; National Archives.

[13] Ibid.; Adjutant General’s Office, Court Martial Case File for John F. Tritle, Principal Record Division, file 30412, Record Group: 153, Stack area: 7E3, Row: 17, Compartment 1, Shelf: 4. Research conducted by Vonnie S. Zullo of The Horse Soldier Research Service..

[14] Ibid.

[15] Adjutant General’s Office, Register of Enlistments in the U.S. Army, 1798-1914.

[16] “Feats Before Santiago,” The Daily Republican (Monongahela, Penn., 19 Nov 1898), 3.

[17] Patrick McSherry, photograph courtesy of Frank Brito, “Camp Wikoff,” The Spanish American War Centennial Website! (http://www.spanamwar.com/campwikoff.html), accessed 7 Jun 2015.

[18] Adjutant General’s Office, Court Martial Case File for John F. Tritle.

[19] John Manguso, Images of America: Fort Sam Houston (Charleston: Arcadia Publishing Co., 2012), 13.

[20] Adjutant General’s Office, Court Martial Case File for John F. Tritle.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Carla Joinson, “Beyond Reason,” Indians, Insanity, and American History Blog (http://cantonasylumforinsaneindians.com/history_blog/beyond-reason/) accessed 7 Jun 2015.

[26] Adjutant General’s Office, Court Martial Case File for John F. Tritle.

[27] Adjutant General’s Office, Pension file for John F. Tritle.

[28] Ibid.

[29] “John F. Tritle,” Seattle Daily Times (20 Oct 1939).

[30] Karen Sipe, photo., “Sgt John Franklin Tritle,” FindAGrave (http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=16877494), posted 1 Dec 2006, accessed 16 Feb 2015.

Citation for this article: Samuel L. Russell, “Sergeant John Franklin Tritle, E Troop, 7th Cavalry – Conspicuous Bravery,” Army at Wounded Knee (Sumter, SC: Russell Martial Research, 2013-2015, http://wp.me/p3NoJy-IO) posted 8 Jun 2015, accessed date __________.

![View from inside the quadrangle looking south toward the sally port entrance.[John Manguso, Images of America: Fort Sam Houston (Charleston: Arcadia Publishing Co., 2012), 13.]](https://armyatwoundedknee.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/quadrangle-at-fort-sam-houston.jpg?w=624&h=313)

Hi Sam— Thanks for this very interesting piece. I’ve printed it out for my WK file. Tritle certainly had a long and interesting career, as well as a strange and difficult conclusion to it. It sounds as though you’re staying busy, and I hope the spring-summer goes well for you. Best wishes, Jerry

P.S. I noticed that Tritle’s name is misspelled on his grave marker. Oops! >

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Sam, if I may, a cousin of mine sent your essay – both of us found it very interesting! Would you be interested in publishing another version of this, one that assesses Wounded Knee as something other than a “battle”, also the impact of war and trauma on combatants. My name is Larry Tritle, teaching at Loyola Marymount University in LA. I’ve published a number of works on war and trauma, among other things. Contact information follows.

LikeLike

Mr. Tritle… Thank you for your interest. Unfortunately, I am swamped with projects right now, and have not made as much progress on my documenting the lives of the troopers, artillerymen, and hospital corpsmen that fought at Wounded Knee. Though your suggestion of publishing another version of this post is intriguing, I am not taking on additional projects at this time. For a glimpse at my view of Wounded Knee as a battle–tragic yes, but a battle nonetheless–vice a massacre, I suggest reading one of my earlier posts, Comments on Wounded Knee.

Regards, Sam

LikeLike